Hong Kong Med J 2015 Dec;21(6):528–35 | Epub 16 Oct 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144457

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Early postoperative outcome of bipolar transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate

CL Cho, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery);

Clarence LH Leung, MRCSEd;

Wayne KW Chan, FRCSEd (Urol);

Ringo WH Chu, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery);

IC Law, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)

Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CL Cho (chochaklam@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To report the early

postoperative outcome of bipolar transurethral

enucleation and resection of the prostate. Our

results were compared with those published from

various centres.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Regional hospital, Hong Kong.

Patients: A total of 28 consecutive patients who had

undergone bipolar transurethral enucleation and

resection of the prostate by a single surgeon between

January and June 2014. All patients were evaluated

preoperatively by physical examination, digital

rectal examination, transrectal ultrasonography,

and laboratory studies, including measurement of

haemoglobin, sodium, and prostate-specific antigen

levels. Patients were assessed perioperatively and at

4 weeks and 3 months postoperatively.

Results: The mean resected specimen weight of

prostatic adenoma in 28 patients was 48.2 g with

a mean enucleation and resection time of 13.6

and 47.7 minutes, respectively. There was a mean

decrease in serum prostate-specific antigen by 85.9%

(from 6.4 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL) postoperatively.

Prostate volume was decreased by 68.2% (from

71.9 cm3 to 22.9 cm3) at 4 weeks postoperatively.

The mean postoperative haemoglobin drop was

11.5 g/L. The rate of transient urinary incontinence

at 3 months was 3.6%. Patients who underwent

bipolar transurethral enucleation and resection of

the prostate had a short catheterisation time and

hospital stay, which is comparable to conventional

transurethral resection of the prostate.

Conclusions: Bipolar transurethral enucleation

and resection of the prostate should become the

endourological equivalent to open adenomectomy

with fewer complications and short convalescence.

The technique of bipolar transurethral enucleation

and resection of the prostate can be acquired safely

with a relatively short learning curve.

New knowledge added by this study

- Bipolar transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate (TUERP) achieves satisfactory early functional outcomes and is associated with low morbidity. The technique is applicable to prostates of all size.

- Outcomes comparable with large case series could be achieved with a short learning curve.

- Bipolar TUERP should be the technique of choice for a large-sized prostate.

- Bipolar TUERP is an alternative to conventional transurethral resection for small and medium-sized prostates.

Introduction

Despite the availability of numerous minimally

invasive techniques, transurethral resection of the

prostate (TURP) remains the most common surgical

treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

caused by benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) in

small to medium-sized prostates.1 Nonetheless,

TURP has been associated with significant

complication rates.2

Bipolar TURP uses saline irrigation, which

decreases the risk of TURP syndrome compared

with monopolar TURP, and both bipolar and

monopolar TURP result in comparable functional

outcomes.3 The bipolar system can also be broadened

to enucleate the prostate gland along the surgical

capsule, using a resectoscope combined with a loop.

This transurethral enucleation and resection of the

prostate (TUERP) technique can potentially remove

more prostatic tissue than TURP and requires no

additional devices.

In the present study, we describe the technique

and early postoperative outcomes of bipolar TUERP

and compare our results with major international

series.

Methods

Patients

Between January 2014 and June 2014, 28 consecutive

patients underwent bipolar TUERP at Kwong Wah

Hospital, Hong Kong. All patients were evaluated

preoperatively by physical examination, digital

rectal examination, transrectal ultrasonography

(TRUS) of the prostate, and laboratory studies that

included measurement of haemoglobin, sodium,

and prostate-specific antigen (PSA). Patients were

offered the option of ultrasound-guided transrectal

prostate biopsy if the PSA level was >4 ng/mL or if

the digital rectal examination showed suspicion of

prostate cancer. Abnormal digital rectal examination

findings included prostate nodule, asymmetry of the

lateral lobes, or irregularity of the prostate. The TRUS

was performed to measure the maximum length,

width, and anteroposterior height of the prostate

to calculate the prostate volume using the ellipse

formula, where prostate volume (mL) = 0.52 x length

x width x height. Patient baseline characteristics,

indications for surgery, and operative data and

complications were recorded by doctors. Patients

with neurogenic bladder, previous genitourinary

tract surgery, urethral stricture, or known bladder

or prostate carcinoma were excluded from the

technique of bipolar TUERP.

Equipment and technique

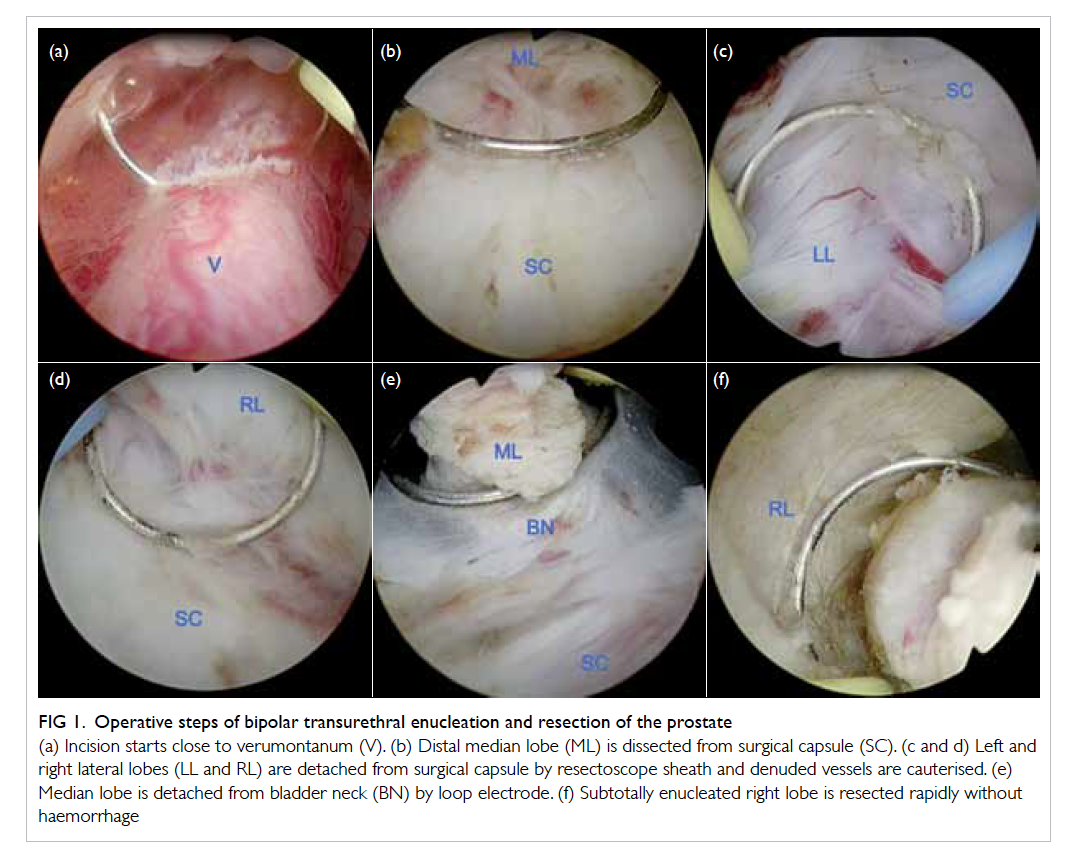

All bipolar TUERP procedures were performed

by a single surgeon. This surgeon had performed

37 TUERPs using various techniques and devices

previously, before the procedure was standardised

as described below and shown in Figure 1. The

technique used in this report was first described by

and adopted from Prof CX Liu at Zhujiang Hospital

of Southern Medical University in Guangzhou.4

Figure 1. Operative steps of bipolar transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate

(a) Incision starts close to verumontanum (V). (b) Distal median lobe (ML) is dissected from surgical capsule (SC). (c and d) Left and right lateral lobes (LL and RL) are detached from surgical capsule by resectoscope sheath and denuded vessels are cauterised. (e) Median lobe is detached from bladder neck (BN) by loop electrode. (f) Subtotally enucleated right lobe is resected rapidly without haemorrhage

Antiplatelet medications were stopped 3

days prior to surgery. Patients received general

or spinal anaesthesia and were placed in the

lithotomy position. Bladder stones where present

were fragmented with a holmium laser via a 21-Fr

rigid cystoscope and were evacuated with an Ellik

evacuator before bipolar TUERP. A 26-Fr Olympus

SurgMaster TURis resectoscope (Olympus Europe,

Hamburg, Germany) with a standard loop was used.

The incision was begun immediately proximal to the

verumontanum using a cutting current. The surgical

capsule plane was identified, and the whole gland

dissected in a retrograde fashion from the cleavage

plane using the resectoscope sheath, until the

circular fibres of the bladder neck were identified.

The loop electrode was used to coagulate all of the

denuded vessels immediately during the detachment

process. The adenoma was subtotally enucleated

with a narrow pedicle attached to the bladder neck at

the 6 o’clock position. The devascularised adenoma

was rapidly resected in pieces by the loop electrode.

The bladder neck at 5 to 7 o’clock was removed if

it appeared relatively high. The anterior commissure

at 12 o’clock was preserved except when it appeared

obstructive endoscopically. The chips were evacuated

with an Ellik evacuator. Finally, the prostatic fossa

was inspected and haemostasis secured. A 24-Fr

three-way urethral catheter was inserted at the end

of the procedure for bladder irrigation. One of the

patients in the series had open inguinal hernia repair

performed after bipolar TUERP. Haemoglobin level

and serum sodium concentration were measured

on the same day after surgery. The protocol for

postoperative care following bipolar TUERP was the

same as that for monopolar and bipolar TURP in our

unit. Bladder irrigation was stopped the following

morning, and the catheter was removed on the

second day postoperatively.

Follow-up

All patients were evaluated following bipolar TUERP

during clinic visits at 4 weeks and 3 months. At each

visit, history, physical examination, International

Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and TRUS of the

prostate were evaluated. The presence or absence

of transient urinary incontinence was documented

with direct questioning of the patient. Uroflowmetry

was performed at 8 weeks, and serum PSA levels

were measured at 3 months.

Results

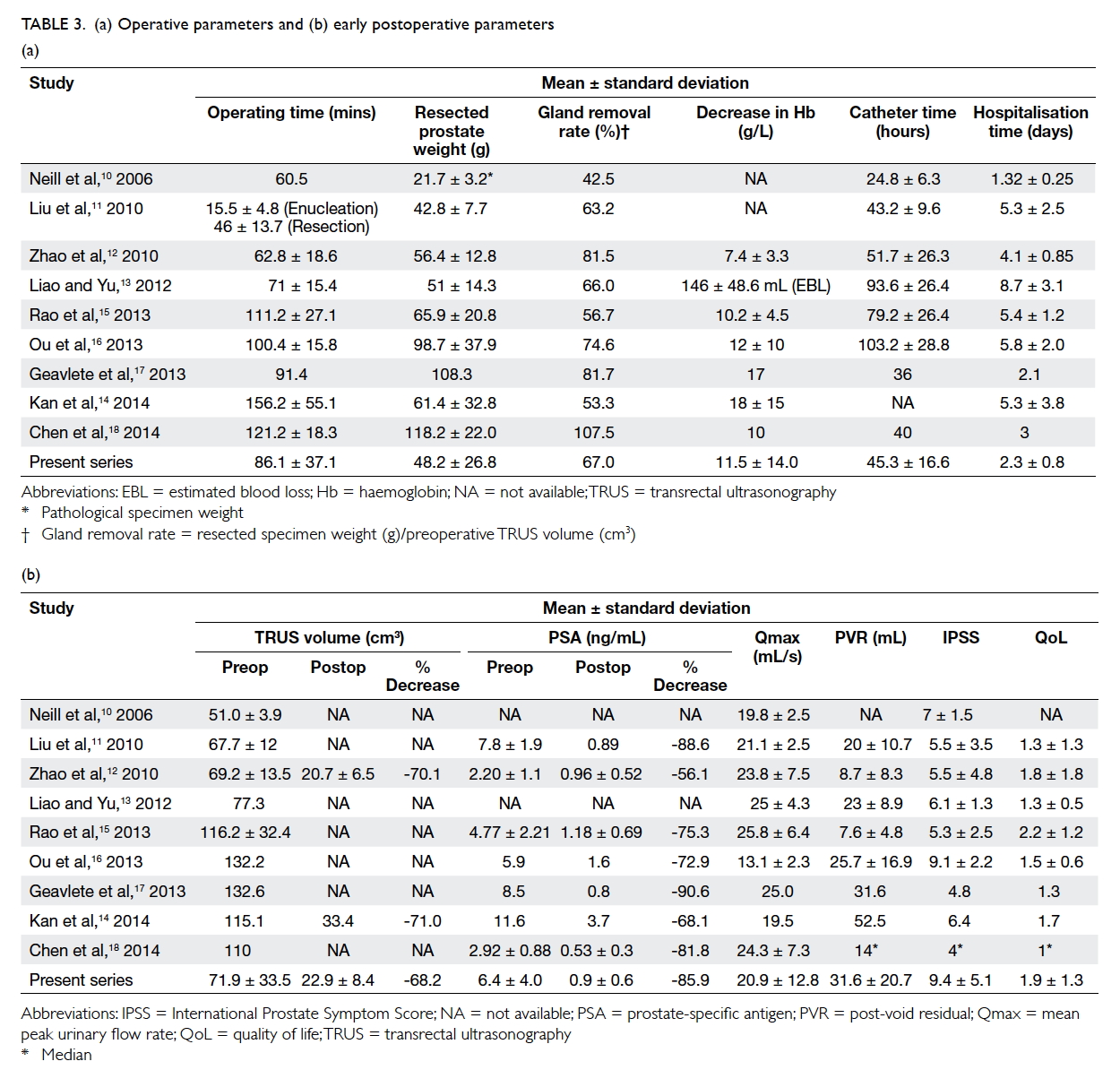

Table 1 lists the patients’ baseline characteristics,

operative data, and early postoperative outcomes.

Enucleation time was defined as the time from

incision to completion of subtotal enucleation

of the adenomatous tissue. Resection time was

defined as the time needed for fragmentation of the

en-bloc adenoma into chips. The mean enucleation

and resection times were 13.6 (median, 15; range,

10-30) minutes and 47.7 (median, 35; range, 15-120)

minutes, respectively, with a mean of 48.2 g of

adenoma resected.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, operative data, and early postoperative outcomes in patients with transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate

The mean PSA level decreased from 6.4 ng/mL to

0.9 ng/mL at 3 months postoperatively, representing

an 85.9% decrease. Pathological examination of

enucleated tissue revealed prostatic adenocarcinoma

in one patient who had T1a disease with a Gleason

score of 6; the serum PSA level decreased from 4.6 ng/mL

to 1.7 ng/mL in this patient. There was a significant

decrease in mean TRUS volume from 71.9 cm3 to

22.9 cm3 at 4 weeks and to 15.1 cm3 at 3 months

postoperatively, corresponding to decreases of 68.2%

and 79.0% at 4 weeks and 3 months, respectively.

More than half of the patients in our series

(16 of 28 patients) presented with refractory acute

urinary retention or obstructive uropathy and

had required catheterisation prior to surgery.

Preoperative uroflowmetry within the last year

was available in only 15 patients, thus comparison

between preoperative and postoperative urodynamic

parameters was less representative. The mean peak

urinary flow rate was 20.9 mL/s, and the

mean post-void residual was 31.6 mL at 8 weeks

postoperatively. The mean IPSS was 9.4, and the mean

quality-of-life score was 1.9 at 4 weeks.

There was no requirement for blood

transfusion nor incidence of clot retention in any

patient. The mean decrease in haemoglobin was

11.5 g/L. Urinary tract infection presenting as acute

epididymitis was noted in two (7.1%) patients. One

(3.6%) patient required re-catheterisation on day 2

postoperatively and was successfully weaned off the

catheter on day 5. Transient urinary incontinence

was noted in three patients and one patient at 1 and 3 months

postoperatively, respectively (10.7% at 1 month and

3.6% at 3 months). An average of two incontinence

pads were required daily, and all cases of transient

urinary incontinence subsided within 4 months. No

urethral stricture, meatal stenosis, or bladder neck

contracture was noted at 3 months.

Discussion

The TURP has been considered the standard

surgical therapy for LUTS caused by BPE. Despite

improvements in equipment and techniques over

the years, TURP remains associated with significant

morbidity and re-treatment rates, particularly in

patients with a large prostate.5 Open prostatectomy

(OP) is therefore still considered a valid option for

patients with a prostate of >80 g.6

Surgical enucleation for the treatment of LUTS

caused by BPE remains the most complete method to

remove adenomas of any size; the history of surgical

enucleation dates back more than 100 years.7 In spite

of the low re-operation rate and high success rate,

OP is an invasive procedure associated with higher

transfusion rates, longer catheterisation time, and

longer hospital stay. As a result, the popularity of OP

has declined.

The concept of surgical enucleation was

revisited with the advent of endoscopic alternatives

to open enucleation. Endoscopic enucleation allows

for maximal removal of the adenoma and results in

potentially equivalent efficacy compared with its

open counterpart, with significantly lower morbidity.

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP)

was the first endoscopic enucleative technique

described.8 This technique has been compared with

OP and TURP in various randomised controlled

trials, yielding at least comparable outcomes and

a favourable safety profile.9 The use of expensive

high-energy holmium laser equipment and a steep

learning curve, however, have limited the extensive

application of HoLEP worldwide. There has also

been a significant risk of bladder injury associated

with the use of the mechanical tissue morcellator

that is required for HoLEP.

The use of normal saline as an irrigant was

made possible by the introduction of bipolar devices.

As a result, the risk of TURP syndrome has been

virtually eliminated, and bipolar TURP has been

widely adopted for resection of larger prostates with

longer operating times. The use of a bipolar device

in endoscopic enucleation was first reported by Neill

et al,10 and bipolar TUERP requires no additional

devices in comparison with bipolar TURP. Moreover,

the sheath of the resectoscope is used for mechanical

enucleation of the adenoma along the plane of the

surgical capsule, instead of the holmium laser used

in HoLEP. The subtotally enucleated adenoma is then

resected into chips by the loop electrode, and the use

of a mechanical tissue morcellator is eliminated.

The nomenclature for this procedure has

not been standardised, with terms such as TUERP,

plasmakinetic enucleation of the prostate, and

bipolar plasma enucleation of the prostate reported

in the literature. All of these names generally refer

to the same procedure with minor differences. The

term ‘bipolar TUERP’ is used in this article.

Several modifications in technique and

equipment since the introduction of bipolar TUERP

have been suggested. For example, a spatula-like

enucleation loop, combined with a loop electrode

for haemostasis, was introduced by Olympus and is

especially designed for this procedure. Alternatively,

the use of thick loop electrodes and button electrodes

has been described in some series to facilitate the

enucleation process. Based on personal experience

with these different loops, the alternative loops with

different designs are generally stronger than the

conventional loop electrode, and they can be used

for mechanical enucleation without breakage. The

use of the loop in performing enucleation, instead of

the resectoscope sheath, also provides better, more

direct visualisation during the enucleation process

and potentially shortens the learning curve and

improves the safety of the procedure, particularly

in the early phase of learning. The resectoscope

sheath, however, facilitates a shorter enucleation

time without compromising safety with the

surgeon’s experience. The initial technique adopted

for bipolar TUERP was the ‘three-lobe’ technique.

This procedure starts with deep incisions down to

the surgical capsule at the 5 and 7 o’clock positions

from the bladder neck to the verumontanum, with

an additional incision at the 12 o’clock position

also reported. The median and lateral lobes of

the prostate are then subtotally enucleated and

resected in sequence. Some authors have reported

‘hybrid’ techniques, with the median lobe resected

as in conventional TURP and only the lateral lobes

enucleated. It has also been noted that deep incisions

might not be necessary, as the surgical capsule plane

can generally be identified with a small incision

immediately proximal to the verumontanum, and the

whole gland can be enucleated without separation

of the lobes. This procedure avoids the bleeding

associated with deep incisions of the bladder neck

and adenoma although a small lobe can sometimes

be difficult to enucleate after separation of the lobes.

The 12 o’clock incision has been mostly abandoned,

as has also been advocated for HoLEP. The anterior

commissure, particularly the distal part, has been

preserved to decrease the rate of transient urinary

incontinence postoperatively. The technique used

in our centre is currently the most widely practised

among different centres.

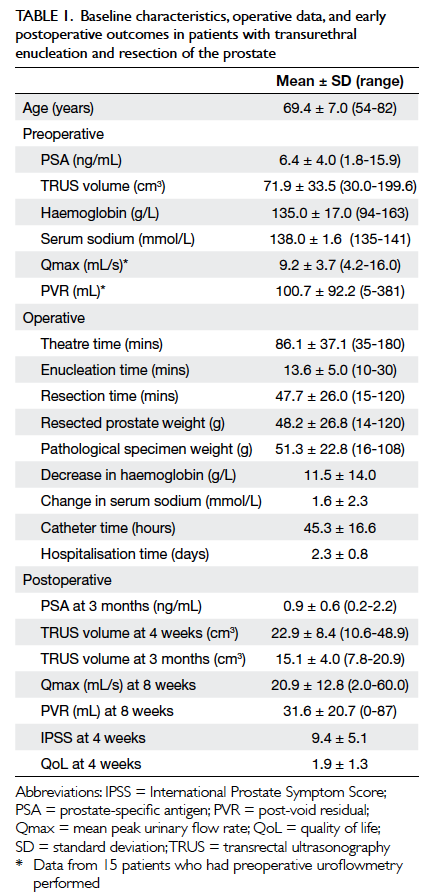

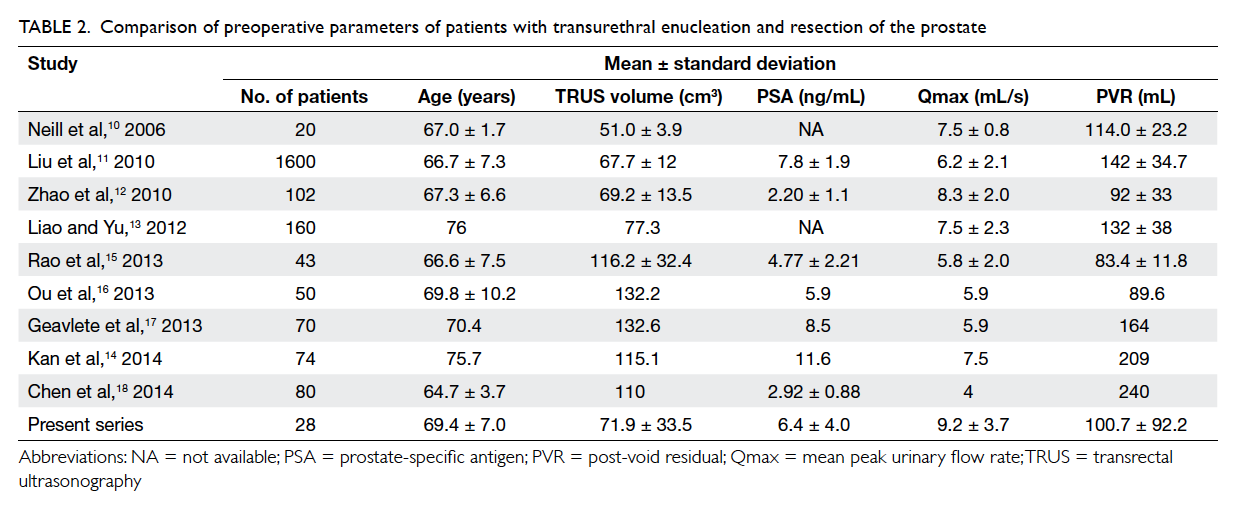

Several series have reported the perioperative

outcomes of bipolar TUERP using similar surgical

techniques. Only the largest series from each centre

was included for comparison; most of the published

series are from China. The results of our series were

compared with the TUERP arms of the various

published series; this list of series and a comparison

of the preoperative parameters are listed in Table 2. After the first published article by Neill et al10

comparing HoLEP and bipolar TUERP in 2006, Liu

et al11 published the largest series with 1600 patients

in 2010. Zhao et al12 and Liao and Yu13 followed by

comparing bipolar TUERP and TURP in medium-sized prostates. Kan et al14 compared bipolar TUERP and TURP in large prostates, and Rao et al,15 Ou

et al,16 Geavlete et al,17 and Chen et al18 compared

bipolar TUERP with OP. The operative and early

postoperative outcomes of bipolar TUERP from

various studies are listed in Table 3.

Table 2. Comparison of preoperative parameters of patients with transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate

The operating time was generally longer

when the preoperative TRUS volume and resected

prostate weight increased. Although Liu et al11

reported enucleation and resection times without

reporting the total operating time, the preoperative

TRUS volume and resected prostate weight were

comparable between Liu et al’s report11 and

our series. In addition, the resection time was

prostate-size–dependent, and a resection efficacy of

approximately 1 g/min was reported in both Liu et

al’s report11 and our series. The enucleation time was

less size-dependent, varying from 10 to 30 minutes,

despite the large range of prostate sizes in our series.

The decrease in haemoglobin of approximately

10 g/L was reported for both medium-sized and large

prostates. Early control of denuded vessels during

the enucleation process made the removal of large

glands possible, with minimal blood loss during the

resection process.

The catheterisation and hospitalisation times

varied greatly among the series evaluated. Longer

times for both have typically been reported in series

from China.11 12 13 15 16 18 In addition, no standard protocols

were stated in most of the series, and the decision

for catheter removal and hospital discharge were

at the discretion of the surgeons. We report short

catheterisation and hospitalisation times with the

adoption of the same protocol as TURP in our

institution. Specifically, bladder irrigation was

stopped on postoperative day 1, the catheter was

removed, and the patient was discharged from the

hospital on postoperative day 2. A total of 92.9% of

the patients (26 of 28 patients) complied with the

postoperative protocol.

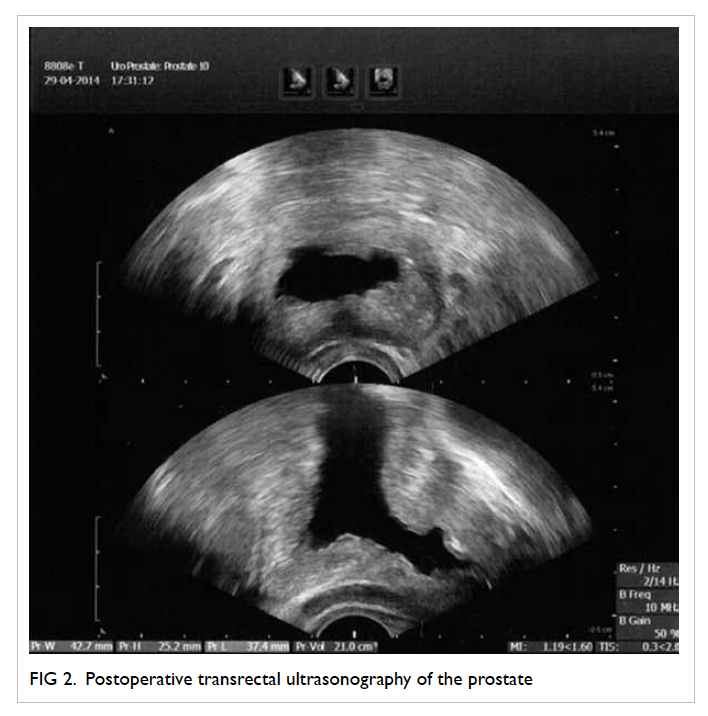

Postoperative TRUS volume was rarely reported

by the series despite the consistent reporting of

preoperative volume. This lack of reporting reflects

the difficulty in accurately estimating residual tissue

volume by TRUS, as illustrated by the postoperative

TRUS photo shown in Figure 2. In addition, the central cavity remaining after TUERP can lead

to overestimation of the prostate volume with

the application of the traditional ellipse formula.

Instead, preoperative estimation of the peripheral

zone volume, obtained by subtracting the volume

of the central zone from the total prostate volume,

may represent a better method for estimating the

residual tissue volume after TUERP. A decrease in

TRUS volume of approximately 70% after TUERP

was consistently reported, despite the pitfalls of

postoperative TRUS measurements.

It has also been shown from the experience of

HoLEP that a reduction in PSA level correlated with the

amount of prostate tissue removed.19 Thus, serum

PSA may serve as a better surrogate marker in the

estimation of postoperative residual tissue volume.

A postoperative PSA level of approximately 1 ng/mL

and a decrease in PSA by >70% were commonly

reported in most of the series.

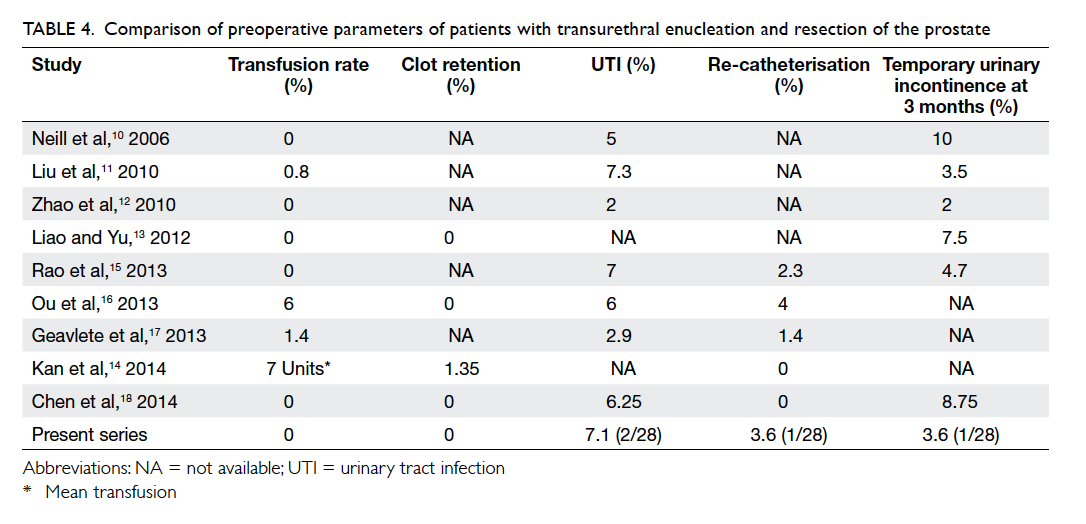

Adverse events were poorly and inconsistently

reported, as shown in Table 4. The standard Clavien classification was not adopted. There was no

Clavien grade 3 or 4 complication in our series. The

transfusion rate was low, with the exception of the

series by Ou et al,16 and clot retention was rare. The

rate of urinary tract infection ranged from 2% to

7.3%, and the re-catheterisation rate was <5%. Major

complications were not common but did occur, as

reported by Kan et al14; four admissions to intensive

care units and nine conversions to other procedures

were reported in this series of 74 patients. The rate

of urethral stricture or bladder neck stenosis was low

and comparable with conventional TURP as reported

by the series by Liu et al.11 Long-term outcome was

not reported in our series due to the short duration

of follow-up. Temporary urinary incontinence was

the major concern with enucleative procedures, and

OP resulted in temporary urinary incontinence in

approximately 10% of cases. The reporting of transient

urinary incontinence after TUERP was poor and

did not feature in three of the nine series analysed.

Furthermore, the definition, timing, and severity of

urinary incontinence were not stated in the other

studies. Dramatic changes in the symptomatology of

the patients over time following benign prostatic hyperplasia–related surgery,

however, likely explain the difficulty in defining

transient urinary incontinence. In our experience,

transient urinary incontinence is not uncommon

after TURP, although it is difficult to differentiate the

type of urinary incontinence, stress, urge or mixed,

by history or urodynamic studies. The natural history

of this phenomenon has rarely been reported in the

literature. It was interesting to note that the rate of

transient urinary incontinence was much higher for

the TURP group (16.1%) compared with the TUERP

group (7.5%) in the series by Liao and Yu.13 In our

experience, 17.9% of patients reported episode(s) of

urinary incontinence at any time point after TUERP;

the rate of transient urinary incontinence was

10.7% and 3.6% at 1 and 3 months postoperatively,

respectively. Patients who had transient urinary

incontinence used two pads daily on average, and all

cases of transient urinary incontinence subsided by

4 months. Further investigations with, for example,

measurement of pad weight and urodynamic studies

will better delineate the cause and natural history of

postoperative transient urinary incontinence. There

is currently no predictive factor identified for the

phenomenon.

Table 4. Comparison of preoperative parameters of patients with transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate

Comparison of outcome and complications

between patients with and without urinary retention

was limited by the small patient number in our study.

No significant difference between outcome and

complications was identified even though patients

with retention were significantly older.

A learning curve of 50 cases was reported for

HoLEP,20 and this learning curve was expected to

be shorter for bipolar TUERP. The instrumentation

for TUERP should be familiar to an endourologist

experienced in TURP because no additional devices

are required. Xiong et al21 analysed the learning

curve of bipolar TUERP. The ratio of conversion to

conventional TURP decreased after 30 cases, and

the efficiency of enucleation and resection increased

with accumulative experience after 50 cases. Our

series showed that the early postoperative outcomes

were comparable to those of large series after

approximately 35 cases, without an increase in

adverse events. The findings were based on analysis

of the learning curve of a single surgeon and may

not be applicable to all surgeons. Nevertheless, an

estimation of a learning curve in a magnitude of 30

to 50 cases seems reasonable and serves as a valuable

reference.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that bipolar TUERP is a safe

technique for prostates of any size. This procedure

should become the endourological equivalent to

open adenomectomy, with fewer complications and

shorter convalescence. This technique can also be

acquired safely with a relatively short learning curve.

References

1. AUA Practice Guidelines Committee. AUA guideline

on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003).

Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J

Urol 2003;170:530-47. Crossref

2. Madersbacher S, Lackner J, Brössner C, et al. Reoperation,

myocardial infarction and mortality after transurethral and

open prostatectomy: a nation-wide, long-term analysis of

23,123 cases. Eur Urol 2005;47:499-504. Crossref

3. Mamoulakis C, Ubbink DT, de la Rosette JJ. Bipolar

versus monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate:

a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Eur Urol 2009;56:798-809. Crossref

4. Liu C, Zheng S, Li H, Xu K. Transurethral enucleative

resection of prostate for treatment of BPH. Eur Urol 2006;5

Suppl:234. Crossref

5. Rassweiler J, Teber D, Kuntz R, Hofmann R. Complications

of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)—incidence, management, and prevention. Eur Urol

2006;50:969-79; discussion 980. Crossref

6. Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, et al. EAU guidelines

on the treatment and follow-up of non-neurogenic male

lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic

obstruction. Eur Urol 2013;64:118-40. Crossref

7. Freyer PJ. Total enucleation of the prostate. A further series

of 550 cases of the operation. Br Med J 1919;1:121-120.2.

8. Gilling PJ, Kennett KM, Fraundorfer MR. Holmium laser

enucleation of the prostate for glands larger than 100

g: an endourologic alternative to open prostatectomy. J

Endourol 2000;14:529-31. Crossref

9. Ahyai SA, Gilling P, Kaplan SA, et al. Meta-analysis

of functional outcomes and complications following

transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms

resulting from benign prostatic enlargement. Eur Urol

2010;58:384-97. Crossref

10. Neill MG, Gilling PJ, Kennett KM, et al. Randomized trial

comparing holmium laser enucleation of prostate with

plasmakinetic enucleation of prostate for treatment of

benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 2006;68:1020-4. Crossref

11. Liu C, Zheng S, Li H, Xu K. Transurethral enucleation

and resection of prostate in patients with benign prostatic

hyperplasia by plasma kinetics. J Urol 2010;184:2440-5. Crossref

12. Zhao Z, Zeng G, Zhong W, Mai Z, Zeng S, Tao X. A

prospective, randomised trial comparing plasmakinetic

enucleation to standard transurethral resection of the

prostate for symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia:

three-year follow-up results. Eur Urol 2010;58:752-8. Crossref

13. Liao N, Yu J. A study comparing plasmakinetic enucleation

with bipolar plasmakinetic resection of the prostate for

benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol 2012;26:884-8. Crossref

14. Kan CF, Tsu HL, Chiu Y, To HC, Sze B, Chan SW.

A prospective study comparing bipolar endoscopic

enucleation of prostate with bipolar transurethral resection

in saline for management of symptomatic benign prostate

enlargement larger than 70 g in a matched cohort. Int Urol

Nephrol 2014;46:511-7. Crossref

15. Rao JM, Yang JR, Ren YX, He J, Ding P, Yang JH.

Plasmakinetic enucleation of the prostate versus

transvesical open prostatectomy for benign prostatic

hyperplasia >80 mL: 12-month follow-up results of a

randomized clinical trial. Urology 2013;82:176-81. Crossref

16. Ou R, Deng X, Yang W, Wei X, Chen H, Xie K. Transurethral

enucleation and resection of the prostate vs transvesical

prostatectomy for prostate volumes >80 mL: a prospective

randomized study. BJU Int 2013;112:239-45. Crossref

17. Geavlete B, Stanescu F, Iacoboaie C, Geavlete P. Bipolar

plasma enucleation of the prostate vs open prostatectomy

in large benign prostatic hyperplasia cases—a medium

term, prospective, randomized comparison. BJU Int

2013;111:793-803. Crossref

18. Chen S, Zhu L, Cai J, et al. Plasmakinetic enucleation of the

prostate compared with open prostatectomy for prostates

larger than 100 grams: a randomized noninferiority

controlled trial with long-term results at 6 years. Eur Urol

2014;66:284-91. Crossref

19. Tinmouth WW, Habib E, Kim SC, et al. Change in serum

prostate specific antigen concentration after holmium laser

enucleation of the prostate: a marker for completeness of

adenoma resection? J Endourol 2005;19:550-4. Crossref

20. Shah HN, Mahajan AP, Sodha HS, Hegde S, Mohile PD,

Bansal MB. Prospective evaluation of the learning curve

for holmium laser enucleation of the prostate. J Urol

2007;177:1468-74. Crossref

21. Xiong W, Sun M, Ran Q, Chen F, Du Y, Dou K. Learning

curve for bipolar transurethral enucleation and resection

of the prostate in saline for symptomatic benign prostatic

hyperplasia: experience in the first 100 consecutive

patients. Urol Int 2013;90:68-74. Crossref