Hong Kong Med J 2015 Dec;21(6):511–7 | Epub 6 Nov 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154599

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Rising incidence of morbidly adherent placenta

and its association with previous caesarean

section: a 15-year analysis in a tertiary hospital in

Hong Kong

Katherine KN Cheng, MB, ChB;

Menelik MH Lee, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Katherine KN Cheng (chengkaning@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To identify the incidence of morbidly

adherent placenta in the context of a rising caesarean

delivery rate within a single institution in the past 15

years, and to determine the contribution of morbidly

adherent placenta to the incidence of massive postpartum

haemorrhage requiring hysterectomy.

Design: Case series.

Setting: A regional obstetric unit in Hong Kong.

Patients: Patients with a morbidly adherent placenta

with or without previous caesarean section scar

from 1999 to 2013.

Results: A total of 39 patients with morbidly adherent

placenta were identified during 1999 to 2013. The

overall rate of morbidly adherent placenta was

0.48/1000 births, which increased from 0.17/1000

births in 1999-2003 to 0.79/1000 births in 2009-2013.

The rate of morbidly adherent placenta with previous

caesarean section scar and unscarred uterus also

increased significantly. Previous caesarean section

(odds ratio=24) and co-existing placenta praevia

(odds ratio=585) remained the major risk factors for

morbidly adherent placenta. With an increasing rate

of morbidly adherent placenta, more patients had

haemorrhage with a consequent increased need for

peripartum hysterectomy. No significant difference

in the hysterectomy rate of morbidly adherent

placenta in caesarean scarred uterus (19/25)

compared with unscarred uterus (8/14) was noted.

This may have been due to increased detection of

placenta praevia by ultrasound and awareness of

possible adherent placenta in the scarred uterus,

as well as more invasive interventions applied to

conserve the uterus.

Conclusion: Presence of a caesarean section scar

remained the main risk factor for morbidly adherent

placenta. Application of caesarean section should be

minimised, especially in those who wish to pursue

another future pregnancy, to prevent the subsequent

morbidity consequent to a morbidly adherent

placenta, in particular, massive postpartum haemorrhage and

hysterectomy.

New knowledge added by this study

- The incidence of morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) including its precursor has increased over the last 15 years.

- MAP can occur in a scarred or an unscarred uterus with similar risks of massive postpartum haemorrhage or hysterectomy.

- There is raised awareness of the possibility of MAP in a scarred or an unscarred uterus and the associated risks of massive postpartum haemorrhage and hysterectomy.

Introduction

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP)—including

placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta

percreta—is a life-threatening condition often

associated with massive postpartum haemorrhage

(PPH) and sometimes hysterectomy.1 2 The condition

results in significant maternal morbidity, maternal

mortality, and socio-economic cost in terms of the

need for invasive surgical intervention, prolonged

hospitalisation, and admission to an intensive care

unit.

The incidence of MAP is on the rise.3 4 In a US study, Wu et al5 reported an incidence of 1 in 533

births for the period from 1982 to 2002. This was

much greater than a previous reported range of 1 in

4027 to 1 in 2510 births6 or even 1 in 70 000 births7

in the 1970s to 1980s. A similar Irish retrospective

study with 36 years of data reported a doubling of the

incidence of placenta accreta in patients with previous caesarean

section from 1.06 per 1000 deliveries before

2002 to 2.37 per 1000 deliveries from 2003 to 2010.8

A recent Canadian study also showed an incidence of

14.4 per 10 000 deliveries in 2009 to 2010.9 Although

the majority of data suggested a rise in such trend,

a few suggested otherwise. The American College

of Obstetricians and Gynecologists accepted a rate

of 1 in 2500 deliveries as the true incidence of the

condition in 2002,10 11 while a national case-control

study in the UK suggested the incidence to be only

1.7 per 10 000 pregnancies overall at the end of

2012.12

Morbidly adherent placenta is most commonly

associated with placenta praevia in women previously

delivered by caesarean section.12 13 14 Despite some

variation in the incidence of MAP, there are very few

reported trends of MAP based on data of a single

institution or within a similar population.

In this study, a retrospective review of data

within a single institution in Hong Kong was

performed to (a) identify the change in incidence of

MAP that included placenta accreta, percreta and

increta, in the context of a rising caesarean delivery

rate within a single institution over the last 15 years,

and (b) to determine the contribution of MAP

to obstetric complications, in particular, massive

PPH with consequent hysterectomy.

Methods

Patients with MAP at Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

Hong Kong, over a 15-year period from 1 January

1999 to 31 December 2013 were retrospectively

identified from the hospital database, Clinical Data

Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS). The

research protocol was approved by the hospital’s

ethics committee.

Diagnosis codes for ‘previous caesarean

section’, ‘placenta praeviae, ‘adherent placenta’

‘placenta accreta’, ‘placenta percreta’, and ‘placenta

increta’ were used. Labour ward records with cases

of obstetrics-related hysterectomy or massive PPH

(>1000 mL) were cross-examined along with the

data from CDARS to ensure no cases of MAP were

missed.

Morbidly adherent placenta was defined

primarily by a histopathology report of an adherent

placenta, in which there was invasion of placental

tissue into the inner or outer myometrium or

through the serosa of the uterus, and was termed

placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta

percreta, respectively. It was also defined clinically by

operative reports of a difficult manual removal with

no cleavage plane identified between the placenta

and uterus, resulting in incomplete removal or need

to leave the entire placenta in situ. Histopathology

results were reviewed for each case where available.

The medical records including admission

notes, operative record, and pathology reports

in all of the cases were individually reviewed.

Demographic data, obstetric history, the

number and type of previous caesarean sections, and

information on placenta site were collected. Details

of associated complications, in particular massive

PPH, were reviewed. The subsequent

management plan of MAP was noted and reviewed,

and included (1) conservative management (leaving

part of or the whole placenta in situ) with or without

additional invasive intervention and follow-up, or (2)

immediate invasive intervention (including uterine

or iliac artery embolisation, balloon tamponade,

uterine artery ligation, or hysterectomy).

Cases were then analysed in three different

5-year intervals to identify any changes in the rate

of MAP. These intervals were 1999 to 2003, 2004 to

2008, and 2009 to 2013. Cases of MAP were analysed

in two different groups—a group with scarred uterus

due to previous caesarean section and another group

with unscarred uterus. Their incidence, associated

risk factors, and morbidity associated with MAP

were reviewed and compared.

Statistical analyses were performed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Chi squared

test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables

and independent sample t test or analysis of variance

for continuous variables were applied for analysis.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Over the 15-year study period, there were a total of

81 497 deliveries in our hospital. The mean number

of deliveries before 2004 was 4600 per year but this

figure increased dramatically to a mean of 5800

per year from 2004 to 2013. This is likely due to

the introduction of the ‘Individual Visit Scheme’ in

July 2003, where travellers from Mainland China

are allowed visits and to give birth in Hong Kong

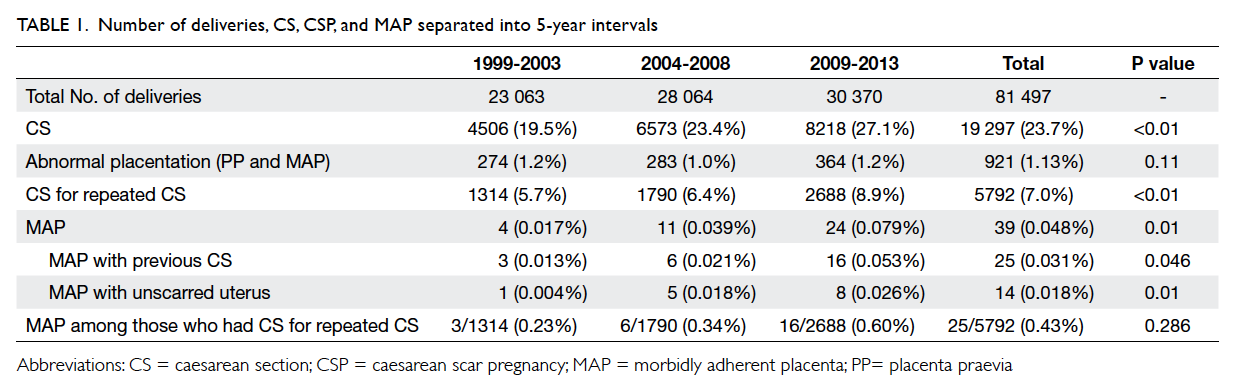

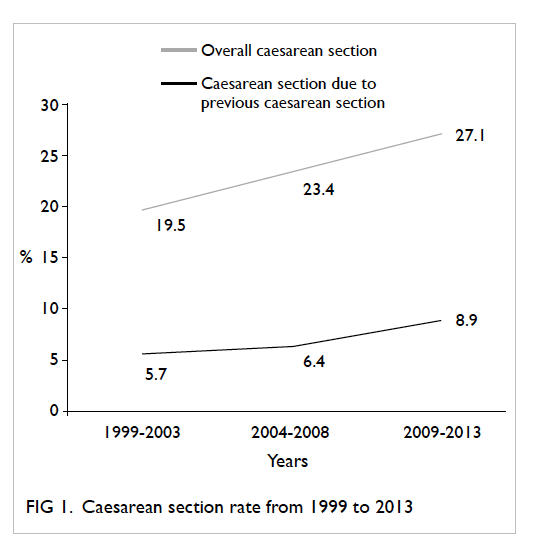

on an individual basis. The overall rate of caesarean

section during the 15-year period was 23.7% and

was increased significantly throughout the years

(P<0.01; Table 1 and Fig 1). As a result, the rate of

caesarean section due to previous caesarean section

also significantly increased from 5.7% in 1999-2003

to 8.9% in 2009-2013 (P<0.01; Table 1 and Fig 1).

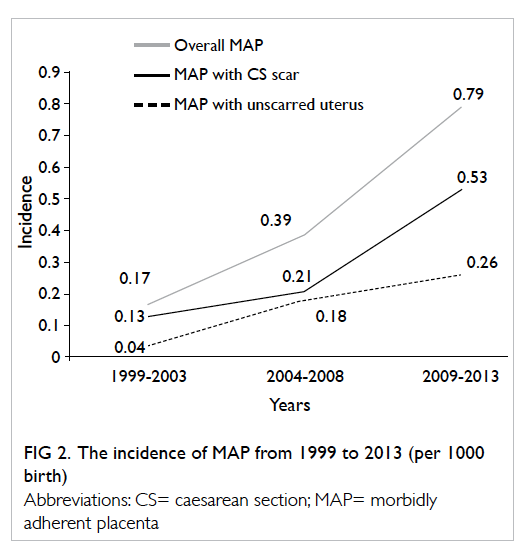

A total of 39 cases of MAP were identified.

The overall rate of MAP was 0.48 per 1000 births,

which has been increased significantly from 1999

to 2013 (P=0.01). Of the 39 cases of MAP, 25 cases

were in a scarred uterus and all deliveries were by

caesarean section; 14 cases were from an unscarred

uterus, of which four were vaginal deliveries and 10

were caesarean section. There were three cases of

placenta percreta and 36 cases of placenta accreta.

The increasing rate of MAP persisted even after

subcategorisation into previous caesarean section

scar or unscarred uterus (Table 1 and Fig 2). There

was also an increasing trend of MAP with caesarean

section scar among cases that had repeated caesarean

section, although the increase was not significant

(P=0.286; Table 1).

The overall incidence of MAP in previous

caesarean section was 0.43% compared with only

0.018% in those with an unscarred uterus. The odds

ratio (OR) of MAP in previous caesarean section was

24 compared with that of unscarred uterus (P<0.05;

95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-45.2).

Among all the cases of placenta praevia

during the study period, the incidence did not differ

significantly with time and remained an average

of 1.13% (P=0.11; Table 1). Among the 39 cases of MAP, 34 cases had pre-existing placenta praevia.

Placenta praevia remained a major risk factor in the

development of MAP (OR=585; 95% CI, 228.3-1399.7).

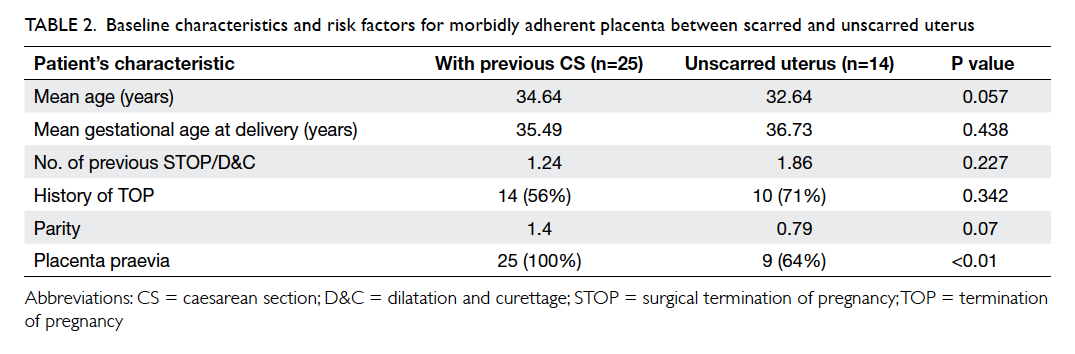

Cases with MAP and a previous caesarean

section were compared with those with an unscarred

uterus. The presence of placenta praevia with a

previous scar increased the risk of MAP significantly

(P<0.01; Table 2). There were no significant differences between the two groups for the majority

of other additional underlying risk factors for MAP.

These included mean parity, maternal age, gestational

age at delivery, and the number of previous surgical

termination of pregnancy or surgical evacuations

(Table 2). Overall, there was one case of MAP following in-vitro fertilisation–induced pregnancy

but no cases had a history of hysteroscopic surgery

or a history of uterine artery embolisation.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics and risk factors for morbidly adherent placenta between scarred and unscarred uterus

Management of morbidly adherent placenta

in scarred versus unscarred uterus

Among the 39 cases of MAP, 14 cases were from an

unscarred uterus, thus there had been no antenatal

suspicion of a possible MAP. Among the remaining

25 cases where MAP was found in a scarred uterus,

24 cases had placenta praevia diagnosed on antenatal

ultrasonography (USG) and one case had no previous

antenatal USG documentation of placental site. In

three cases, there was antenatal suspicion of placenta

accreta with additional measurement made of the

lower segment thickness by USG. None of the three

cases had signs of MAP, thus no antenatal diagnosis

was made or caesarean hysterectomy planned. For

all cases with co-existing placenta praevia diagnosed

antenatally, counselling including the risk of PPH,

need for multiple medical/surgical interventions

and hysterectomy as a last resort was given prior to

caesarean section.

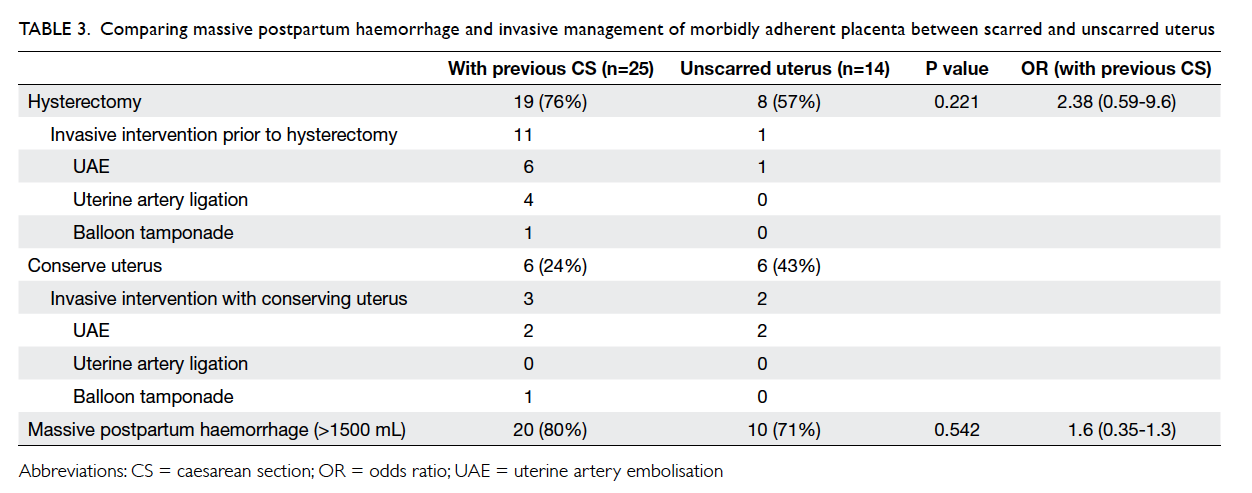

In terms of the diagnosis of MAP, 27 (69%)

cases were confirmed histologically following

hysterectomy. The remaining 12 were diagnosed

clinically. Among those confirmed histologically, 19

cases were from a scarred uterus and eight from an

unscarred uterus. Of 19 cases from a scarred uterus,

11 had undergone previous intervention (uterine

artery embolisation, uterine artery ligation, or

balloon tamponade) before hysterectomy compared

with one in eight cases of unscarred uterus (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparing massive postpartum haemorrhage and invasive management of morbidly adherent placenta between scarred and unscarred uterus

Conservative management with the MAP

tissue left in situ was applied in 12 (31%) cases

of MAP (6 cases from each group): three of the

scarred uterus cases required additional invasive

interventions compared with two of the six cases with

unscarred uterus (Table 3). Three cases defaulted from subsequent follow-up and the remaining nine

cases resolved completely in 8 to 49 weeks’ time.

The majority of cases of MAP in patients with

scarred and unscarred uterus were complicated by

massive PPH of >1500 mL (80% vs 71%). The

rate of hysterectomy in both groups was high: 76%

in the scarred uterus group and 57% in unscarred

uterus group (Table 3), although the difference was not significant.

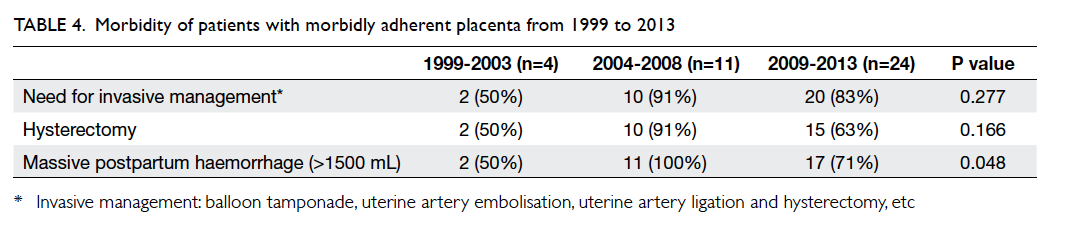

Overall morbidity of morbidly adherent placenta

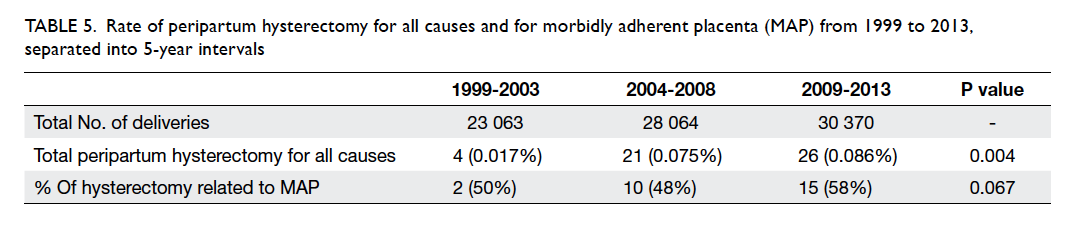

Throughout the 15-year study period, there was

a significant increase in the proportion of MAP

associated with massive PPH (P=0.048). Thus there

was a consequent increased trend, although not

significant, in the need for invasive intervention and

hysterectomy (Tables 4 and 5), which is a life-saving

last-resort procedure in the management of massive PPH.

Table 5. Rate of peripartum hysterectomy for all causes and for morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) from 1999 to 2013, separated into 5-year intervals

Discussion

The data derived from this retrospective study

demonstrate a significant increase in the total

number of deliveries and caesarean sections from

1999 to 2013. With an increasing caesarean section

rate, the number of repeated caesarean sections

also increased. Possible explanations include the

high caesarean section rates in China and concerns

about the reported 4.5 per 1000 risk of previous

caesarean scar rupture.15 An alternative explanation

is the large proportion of patients who declined a

vaginal birth after a previous caesarean section or

who declined induction of labour after a previous

caesarean section. It has been reported that up to

32% to 46% of patients with a history of caesarean

section decline induction.16 The rate of MAP hence

increased as a result of more previous caesarean

sections and concurs with the findings from other

countries.3 4 5 6 7 8 Our study further demonstrated an almost tripling of incidence of MAP in the presence

of previous caesarean section from 0.23 to 0.60 per

1000 births during 2009 to 2013. This may be due to

an increasing awareness of the increasing trend of

MAP, especially in those with a caesarean scar.

Previous caesarean section scar has been

identified as one of the most important risk factors

for MAP. Our study demonstrated a 24 times

greater likelihood of developing MAP with previous

caesarean section scar compared with unscarred

uterus. Placenta praevia in the presence of a previous

caesarean section scar was 585 times more likely to

develop into a MAP. Nonetheless our data failed to

determine other reported demographics17 and risk

factors such as mean parity, maternal age, gestational

age at delivery, and previous surgical termination or

surgical evacuation. Previous surgery on the uterus

other than caesarean section (eg myomectomy)

may also predispose to MAP but among our cases

of adherent placenta, no patient had such a history

so comparisons could not be made. As a result,

every effort should be made to avoid caesarean

section delivery and hence reduce subsequent MAP

development.

Morbidly adherent placenta was more likely in

a scarred uterus although it could also occur in an

unscarred uterus. Although the majority of patients

with MAP in our study had a caesarean scar, 36% had

an unscarred uterus. The mean number of surgical

termination of pregnancy or surgical evacuation of

the uterus in the unscarred uterus group was 1.86

compared with 1.24 in the caesarean section scarred

uterus group. In addition, in the unscarred uterus

group, 71% of patients had a history of surgical

termination of pregnancy compared with 56% in the

caesarean section scarred uterus group, although the

difference was not significant. A recent case study has

reported an abnormally invasive placenta as a result

of uterine scarring in a patient with Asherman’s

syndrome.18 Therefore, awareness of the possible

development of MAP is important in pregnant

women with a history of intrauterine procedure

without caesarean section scar or placenta praevia.

The management of patients with complications

associated with MAP can be challenging. Patients

are more likely to develop massive PPH

with a consequent need for intra-operative invasive

intervention (eg balloon tamponade, uterine artery

ligation/embolisation, and hysterectomy) and

hysterectomy compared with those with a normally

adherent placenta.19

Our data clearly demonstrated an increase

in the incidence of massive PPH as the

incidence of MAP increases. The rate of peripartum

hysterectomy associated with MAP also showed

an increasing trend, albeit insignificant. This could

be due to advances in management, including

increasing USG detection of placenta praevia in the

early antenatal period and awareness of a possibly

adherent placenta in cases with a scarred uterus

that facilitates a delivery plan, as well as multiple

interventions (balloon tamponade, uterine artery

embolisation, uterine artery ligation) attempted

in cases with MAP to conserve the uterus as far as

possible. This was reflected by the increased need for

invasive interventions throughout the study period

although not to a significant degree, possibly due to

the small sample size.

Limitations

This was a retrospective overview of our hospital

data over the last 15 years. Data obtained during

the earlier years when the hospital’s Clinical Record

System was first introduced may be inaccurate.

Similarly, historical data were available for only this

15-year period. Given the overall low incidence of

MAP and the limited data available, the strength of

the statistical significance may well be challenged.

In addition, caesarean scar pregnancy, which is a

precursor of MAP, was not included in this study as

the number of cases was too small and no systemic

data were available. Previous studies have shown

that leaving the placenta in situ can reduce the rate

of hysterectomy.20 This issue was not investigated in

this study.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the incidence of MAP

has increased over the last 15 years. The results also

remind clinicians that MAP is much more likely to

occur if a previous caesarean scar is present (OR=24),

in particular when it is associated with a placenta

praevia (OR=585). The increased caesarean section

rate and subsequent previous caesarean section

scar were major causes for such increase. Morbidly

adherent placenta resulted in an increasing, albeit

insignificant, trend for massive PPH, and the need

for multiple invasive interventions or hysterectomy

over the last 15 years. Early suspicion and diagnosis

is essential to prevent major obstetric complications,

as well as to aid management of massive PPH

resulting from placenta complications. Every effort

should be made to avoid unnecessary caesarean

section, not only to meet the international caesarean

section rate target but also to reduce the overall

incidence of MAP that may result in significant

maternal morbidity and mortality, as well as socio-economic

costs.

References

1. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity

associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet

Gynecol 2006;107:1226-32. Crossref

2. Esakoff TF, Sparks TN, Kaimal AJ, et al. Diagnosis and

morbidity of placenta accreta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2011;37:324-7. Crossref

3. Chattopadhyay SK, Kharif H, Sherbeeni MM. Placenta

praevia and accreta after previous caesarean section. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993;52:151-6. Crossref

4. To WW, Leung WC. Placenta previa and previous cesarean

section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1995;51:25-31. Crossref

5. Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal

placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2005;192:1458-61. Crossref

6. Pridjian G, Hibbard JU, Moawad AH. Cesarean: changing

the trends. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:195-200. Crossref

7. Breen JL, Neubecker R, Gregori CA, Franklin JE Jr. Placenta

accreta, increta, and percreta. A survey of 40 cases. Obstet

Gynecol 1977;49:43-7.

8. Higgins MF, Monteith C, Foley M, O’Herlihy C. Real

increasing incidence of hysterectomy for placenta accreta

following previous caesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol

Reprod Biol 2013;171:54-6. Crossref

9. Mehrabadi A, Hutcheon JA, Liu S, et al. Contribution

of placenta accreta to the incidence of postpartum

hemorrhage and severe postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet

Gynecol 2015;125:814-21. Crossref

10. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen

consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries:

early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A

review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:14-29. Crossref

11. ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG

Committee opinion. Number 266, January 2002: placenta

accreta. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:169-70.

12. Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst

P, Knight M. Incidence and risk factors for placenta accreta/increta/percreta in the UK: a national case-control study.

PLoS One 2012;7:e52893. Crossref

13. Romero R, Hsu YC, Athanassiadis AP, et al. Preterm

delivery: a risk factor for retained placenta. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1990;163:823-5. Crossref

14. Parazzini F, Dindelli M, Luchini L, et al. Risk factors for

placenta praevia. Placenta 1994;15:321-6. Crossref

15. Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP.

Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a

prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2001;345:3-8. Crossref

16. Dodd JM, Crowther CA, Grivell RM, Deussen AR. Elective

repeat caesarean section versus induction of labour

for women with a previous caesarean birth. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2014;(12):CD004906. Crossref

17. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors

for placenta previa–placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1997;177:210-4. Crossref

18. Engelbrechtsen L, Langhoff-Roos J, Kjer JJ, Istre O. Placenta

accreta: adherent placenta due to Asherman syndrome.

Clin Case Rep 2015;3:175-8. Crossref

19. Lee MM, Yau BC. Incidence, causes, complications,

and trends associated with peripartum hysterectomy

and interventional management for postpartum

haemorrhage: a 14-year study. Hong Kong J Gynaecol

Obstet Midwifery 2013;13:52-60.

20. Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ,

Brocklehurst P, Knight M. The management and outcomes

of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta in the UK: a

population-based descriptive study. BJOG 2014;121:62-71. Crossref