© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Water sampler

Samson SY Wong, FRCPath, FHKCPath

Member, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Among the collection of artefacts at the Hong

Kong Museum of Medical Sciences, some are less

glamorous than others. One example is a home-made

water sampler that comprises nothing more

than a glass flask tied to a lead sinker and an iron

basket (Fig 1). When lowered to the desired depth,

the stopper of the container was opened by means of

a string. This simple equipment was used by the old

Bacteriological Institute to obtain a sample of local

sources of potable water to test quality including

measurement of bacterial counts. Technically,

there is nothing complicated about the item, but it

reminds us of one of the key roles of a public health

laboratory.

Figure 1. A home-made water sampler for testing water quality used by the old Bacteriological Institute

When the Bacteriological Institute was

established in 1906 in the wake of the 1894 plague

outbreak (during which the aetiological agent

of plague was discovered in Hong Kong), one

of its key duties was the surveillance of plague

and ectoparasites in captured rats. In the first

Government Bacteriologist Annual Report of 1902,

117 839 rats were examined in 1 year for evidence

of plague.1 The report also reviewed the causes of

death as revealed by postmortem examination at the

Government Public Mortuary. From 1906 onwards,

bacteriological examination of public water supplies

began. Water was collected from Pokfulam, Taitam,

and Cheung Sha Wan supplies, as well as from well

and nullah water.2 From the start of monitoring, the

microbiological quality of potable water in Hong

Kong has been maintained at a very high quality.

The provision of a safe water supply has no doubt

played a crucial role in reducing the incidence of

waterborne infections in Hong Kong.

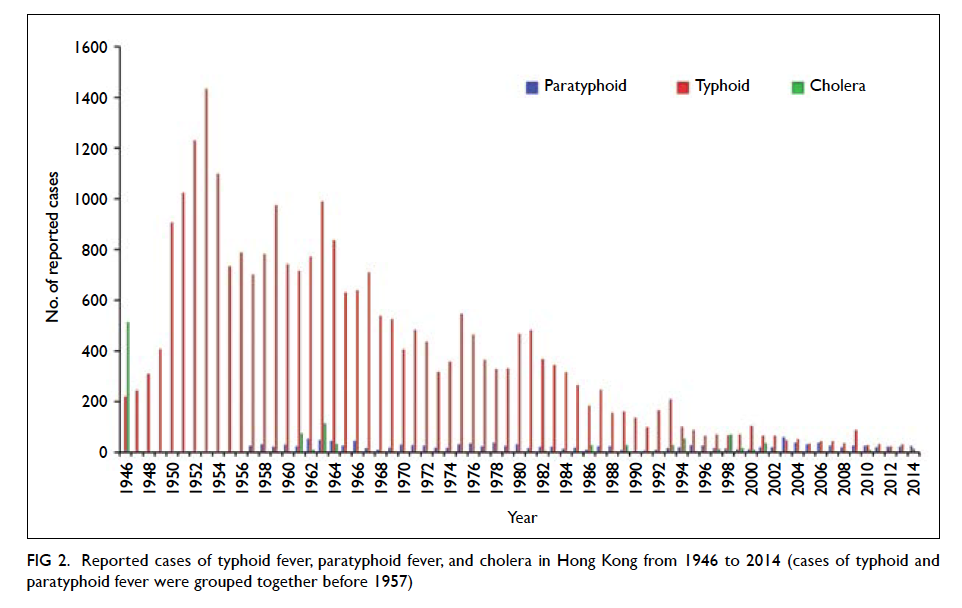

Two classic waterborne infectious diseases,

enteric fever (consisting mainly of typhoid and

paratyphoid fevers) and cholera, featured in the

earliest Report of the Government Bacteriologist. It

was noted that “a very severe outbreak of this disease

[cholera] occurred during 1902 in Hongkong”,1 with

379 fatal cases being examined at the Government

Public Mortuary. In the same year, seven fatal

cases of typhoid fever were examined.1 With the

availability of a safe potable water supply, and hence

lesser reliance on well water and other surface waters

that are prone to faecal contamination, the annual

incidence of both cholera and typhoid/paratyphoid

fevers has substantially reduced over the years

(Fig 2).3 4 The annual number of cholera cases, for

example, has remained a single digit since 2003.4

Figure 2. Reported cases of typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and cholera in Hong Kong from 1946 to 2014 (cases of typhoid and paratyphoid fever were grouped together before 1957)

As the local transmission of cholera and

typhoid/paratyphoid fever becomes rarer, the

epidemiology of these two diseases also changes.

Instead of being a waterborne disease, cholera has

become primarily a food-borne infection in Hong

Kong, often associated with the consumption of raw

or undercooked seafood.5 Indeed, while waterborne

outbreaks of cholera remain a significant public

health problem in developing countries, the majority

of domestic cases of cholera in developed countries

are now food-borne infections.6 Similarly, for

typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, the majority of cases

in developed countries are the result of food-borne

transmission.7 Although domestic transmission

of these infections still occurs in Hong Kong, an

increasing proportion of cases in recent years have

been imported.7 In 2009, 80% of all notified cases

of typhoid in Hong Kong were imported, especially

from Indonesia and India.8

The provision of a safe potable water supply

is one of the most cost-effective interventions

to prevent communicable diseases. The reduced

incidence of waterborne diseases in Hong Kong over

the past century bears testimony to the relationship

between water, sanitation, hygiene, and health.

References

1. Hunter W. Report of the Government Bacteriologist, for the year 1902. Government Public Mortuary, Hong Kong. 1903.

2. Anon. Report of the Government Bacteriologist, for the year 1906. Government Public Mortuary, Hong Kong. 1907.

3. Disease Prevention and Control Division, Department of Health, Hong Kong. Statistics on Infectious Diseases in Hong Kong, 1946-2001. Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 2002.

4. Centre for Health Protection. Number of notifications for notifiable infectious diseases. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/data/1/10/26/43/2280.html. Accessed 29 Sep 2015.

5. Scientific Committee on Enteric Infections and Foodborne Diseases, Centre for Health Protection. Epidemiology, Prevention and Control of Cholera in Hong Kong. 2011. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/epidemiology_prevention_and_control_of_cholera_in_hong_kong_r.pdf. Accessed 14 Aug 2014.

6. Steinberg EB, Greene KD, Bopp CA, Cameron DN, Wells JG, Mintz ED. Cholera in the United States, 1995-2000: trends at the end of the twentieth century. J Infect Dis 2001;184:799-802. Crossref

7. Olsen SJ, Bleasdale SC, Magnano AR, et al. Outbreaks of typhoid fever in the United States, 1960-99. Epidemiol Infect 2003;130:13-21. Crossref

8. Scientific Committee on Enteric Infections and Foodborne Diseases, Centre for Health Protection. Epidemiology and Prevention of Typhoid Fever in Hong Kong. 2011. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/review_of_nontyphoidal_salmonella_food_poisoning_in_hong_kong_r.pdf. Accessed 14 Aug 2014.