DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154525

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

First-trimester medical abortion service in Hong Kong

Sue ST Lo, MD, FRCOG1;

PC Ho, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2

1 The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, 10/F, Southorn Centre,

130 Hennessy Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong

Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Sue ST Lo (stlo@famplan.org.hk)

Abstract

Research on medical abortion has been conducted

in Hong Kong since the 1990s. It was not until 2011

that the first-trimester medical abortion service was

launched. Mifepristone was registered in Hong Kong

in April 2014 and all institutions that are listed in the

Gazette as a provider for legal abortion can purchase

mifepristone from the local provider. This article

aimed to share our 3-year experience of this service

with the local medical community. Our current

protocol is safe and effective, and advocates 200-mg

mifepristone and 400-µg sublingual misoprostol

24 to 48 hours later, followed by a second dose of

400-µg sublingual misoprostol 4 hours later if the

patient does not respond. The complete abortion

rate is 97.0% and ongoing pregnancy rate is 0.4%.

Some minor side-effects have been reported and

include diarrhoea, fever, abdominal pain, and allergy.

There have been no serious adverse events such as

heavy bleeding requiring transfusion, anaphylactic

reaction, septicaemia, or death.

Introduction

In Hong Kong, legal abortion can be performed in

registered institutions in accordance with the legal

requirements stipulated in the Offences against

the Person Ordinance Cap 212. In the past, first-trimester

pregnancies up to 12 weeks of gestation

were terminated by suction evacuation and achieved

a complete abortion rate of 99%.1 Possible risks and

complications, which could affect future fertility,

include heavy bleeding, infection, uterine perforation

with or without bowel injury, and cervical trauma.

With the introduction of mifepristone, a

progesterone antagonist, effective and safe medical

abortion became possible. Over the past three

decades, various medical abortion protocols have

been tested in different countries and Hong Kong has

participated in such research since the 1990s. Most

institutions recommended the use of mifepristone

followed by prostaglandin 24 to 48 hours later to

stimulate uterine contraction and expulsion of the

conceptus. Mifepristone was first registered for

medical abortion in France and China in 1988. By

2013, mifepristone was registered in 60 countries2

and was eventually registered in Hong Kong on 8

April 2014 for medical abortion and cervical priming

before first-trimester surgical abortion (Mifegyne;

Exelgyn, Paris, France). All institutions listed in the

Gazette as a legal abortion provider can purchase

mifepristone from a local provider. The provider

cannot sell mifepristone to an individual doctor or

pharmacy store. Although the posology of Mifegyne

indicates its use for first-trimester medical abortion

up to 63 days of gestation, the treatment is also

effective after 63 days of gestation.3

Most regulatory bodies, including Hong Kong,

approved the use of 600-mg mifepristone for medical

abortion but the International Planned Parenthood

Federation (IPPF),4 World Health Organization

(WHO),5 and Royal College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (RCOG)6 recommended the use of

200 mg as it has similar efficacy and lower cost.7

A prostaglandin has to be given after

mifepristone to stimulate uterine contractions.

Misoprostol is the prostaglandin of choice because

it is cheap, effective, and stable at room temperature

but the dose, route, and timing of administration is

not standardised. The WHO and RCOG recommend

800-µg misoprostol (vaginal, buccal, or sublingual)

24 to 48 hours later.5 6 For women at 50 to 63 days of gestation, the RCOG recommends an additional

400-µg misoprostol (vaginal or oral) 4 hours later if

abortion has not occurred.6 The IPPF recommends

800-µg misoprostol (oral, vaginal, buccal, or

sublingual) at once or in two doses 2 hours apart,

36 to 48 hours later.4 When compared with vaginal

misoprostol, sublingual misoprostol appears to be

associated with a higher rate of gastro-intestinal

side-effects, and buccal misoprostol appears to be

associated with a higher rate of diarrhoea.7

The complete abortion rate for medical

abortion is approximately 95%,1 which is slightly

lower than that for surgical abortion. The chance

of ongoing pregnancy is 1% to 2% and the baby

may suffer from congenital abnormalities due

to prostaglandin. Hence it is recommended that

suction evacuation be performed if medical

abortion fails. Bleeding and abdominal cramps are

inevitable side-effects of medical abortion although

<1% of women need emergency curettage because

of excessive bleeding1 and 0.1% require blood

transfusion.8 In a systematic review of 65 studies

with heterogeneous designs, the overall frequency of

diagnosed or treated pelvic infection after medical

abortion was 0.9%.9 The incidence of suspected or

confirmed post-abortion infection (endometritis,

pelvic inflammatory disease) quoted in the posology

of mifepristone is <5%.10 Very common and common

side-effects of mifepristone include nausea,

vomiting, diarrhoea, light or moderate abdominal

cramps, post-abortion infection, uterine cramps, and

heavy bleeding.10 The side-effects of prostaglandin

observed during medical abortion include transient

fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, headache,

dizziness, and rash.4 The incidence and intensity of

prostaglandin side-effects are determined by the

dose and route of administration.

Our protocols

The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong

(FPAHK) piloted a medical abortion service for

gestation up to 63 days in November 2011. Routine

ultrasound examination was performed to ascertain

the gestation and to exclude multiple pregnancies

and ectopic pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included

hypersensitivity to mifepristone or misoprostol,

multiple pregnancies, haemoglobin level of

<100 g/L, bleeding tendency, known coagulopathy,

use of anticoagulant, current long-term systemic

corticosteroid therapy, history of adrenal tumour/steroid-dependent tumour, chronic adrenal failure,

porphyria, renal/liver impairment, cardiovascular

disease (including arrhythmia, angina, heart

failure, Raynaud’s disease, diastolic hypertension of

>95 mm Hg, arterial hypotension, history of evidence

of thromboembolism), epilepsy, on multiple

medications, inherited porphyria, severe asthma

uncontrolled by therapy, and breastfeeding.

The initial protocol was 200-mg oral mifepristone followed by

800-µg vaginal misoprostol

48 hours later (protocol 1, n=603). Both doses

were administered in the FPAHK. The woman was

permitted to leave after mifepristone administration

provided she did not feel unwell but was required

to remain for observation on the day of misoprostol

administration. Oral paracetamol, oral mefenamic

acid, and intramuscular pethidine were offered for

pain relief. Vital signs, hydration status, and blood

loss were monitored. Most women passed tissue

mass within 4 hours of misoprostol administration.

The doctor routinely performed a pelvic examination

after 4 hours to remove any tissue mass remaining in

the vagina, and to assess blood loss and vital signs.

Any tissue mass collected was sent for pathological

examination to exclude partial mole. The patient was

discharged provided bleeding was not excessive.

In January 2013, this protocol was changed

to 200-mg oral mifepristone followed by 400-µg sublingual misoprostol 48 hours later (protocol 2,

n=890). We changed from vaginal to sublingual

administration because vaginal administration

is intrusive, and requires more consultation

time and more medical consumables. Sublingual

administration requires the woman to place two

tablets of misoprostol under her tongue and then

swallow after 30 minutes. We used a half dose (400

µg) to minimise the severity of gastro-intestinal

reactions that might make patients uncomfortable

and increase the workload of nursing and auxiliary

staff. Since November 2013, women have been given

a second dose of 400-µg sublingual misoprostol

if abortion has not occurred within 4 hours of

misoprostol administration (protocol 3, n=1042).

We hope this regimen will reduce the ongoing

pregnancy rate by administration of the full dose to

selected patients.

Surgical evacuation is performed if there is

heavy bleeding after misoprostol. Manual vacuum

aspiration was introduced as an alternative to

electric vacuum aspiration in January 2014.

Women return for follow-up after 1 week

if abortion has not started on discharge. Other

women are followed up 2 to 3 weeks after the

abortion. Ultrasound examination is performed

in the presence of any abnormal symptoms or

signs. Suction evacuation is arranged for ongoing

pregnancy. Prior to the introduction of 400-µg

sublingual misoprostol after November 2013

(protocol 3), those with persistent bleeding/spotting

and/or retained products of gestation were managed

expectantly or by curettage. An additional dose of

misoprostol is not offered to women with a history

of caesarean section. Further follow-up is arranged

as required, with final follow-up 6 to 8 weeks after

abortion to confirm return of menstruation and

assess their compliance with contraception.

Women are encouraged to start birth control

immediately after misoprostol administration.

Hormonal injectables are given on discharge. Women

are asked to start oral pills on the evening after

misoprostol. A condom should be used consistently

and correctly thereafter. Insertion of an intrauterine

contraceptive device cannot be performed until

abortion has completed and is usually done at the

6-week follow-up.

Outcome

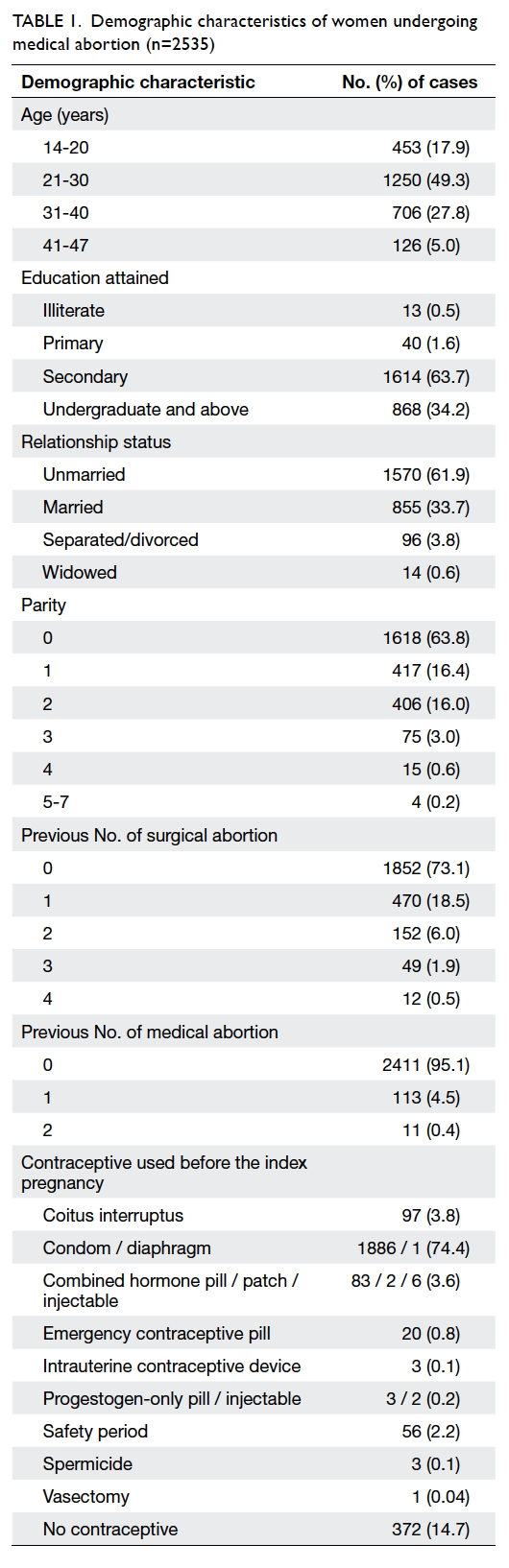

Overall, 2535 medical abortions in 2499 women

were performed in the 3 years from 2011 to 2014.

The median age was 27 years (interquartile range, 11

years). Most women were nulliparous (63.8%), and

mean parity was 0.61 (standard deviation, 0.9). Most

women had no history of surgical (73.1%)

or medical (95.1%) abortion. The demographics are

detailed in Table 1.

Five women took mifepristone only, without

misoprostol. One woman developed palmar

erythema and intense itching 30 minutes after vaginal

misoprostol administration: misoprostol tablets

were removed and douching performed. Allergic

signs and symptoms resolved 15 minutes later.

Suction evacuation was subsequently performed on that

day. This was the 84th case when doctors were still

relatively inexperienced and might have overreacted to

her symptoms. One woman was admitted to hospital

for abdominal pain after mifepristone: ultrasound

examination revealed complete abortion and she was

not given misoprostol during admission. Another

woman was admitted to hospital because of vaginal

bleeding: emergency curettage was performed.

Two women were admitted to hospital because of

persistent vomiting with dehydration. They did not

attend the appointment for misoprostol and suction

evacuation was arranged.

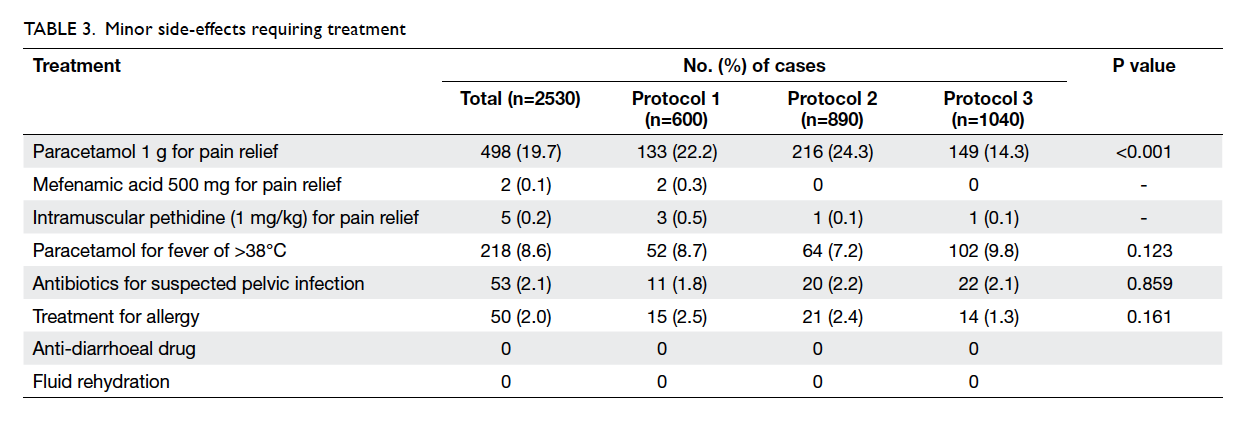

Among 2530 cases admitted for misoprostol,

17 (0.7%) underwent emergency suction evacuation

because of heavy bleeding after misoprostol

administration with 11 having gestation of 56 days

and above. Bleeding stopped after curettage in all

women. The outcomes of medical abortion are listed

in Table 2. After excluding 159 women who did not

return for follow-up, the overall complete abortion

rate was 97.0%. The complete abortion rate in those

with gestation of ≥56 days was significantly lower

than in those with <56 days of gestation (95.7% vs

97.7%; Fisher’s exact test, P=0.007). The complete

abortion rate for protocols 1, 2, and 3 was 96.3%,

97.5%, and 97.1% respectively, and the respective

mean gestation was 51.3 days, 51.7 days, and 51.3

days (P=0.362). The complete abortion rate did not

differ by protocol (P=0.440), parity (P=0.527), or

history of miscarriage and termination of pregnancy

(P=0.246). Among those who had curettage after

medical abortion, 64% were performed within the

first 2 weeks, 14% were between third and fourth

week, and the remaining 22% were between fifth and

12th week. Curettage within the first 4 weeks was

performed for excessive bleeding: those performed

later were for retained products of gestation and

persistent spotting.

Table 2. Outcomes of women who had completed the course of medical abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol

The overall ongoing pregnancy rate was 0.4%

and gestation was between 52 and 60 days. The

ongoing pregnancy rate for protocols 1, 2, and 3 was

0.9%, 0.4%, and 0.2%, respectively (P=0.138). After

changing to protocol 3, 97 (9.3%) women received

a second dose of misoprostol. During follow-up,

49 women received additional misoprostol—seven

during first follow-up for dead fetus in situ, 37 during

first 2 weeks for moderate bleeding, one during the

fourth week for persistent bleeding, and four for

retained products between fourth and eighth week.

One required manual vacuum aspiration in the

12th week because of persistent tissue mass despite

misoprostol.

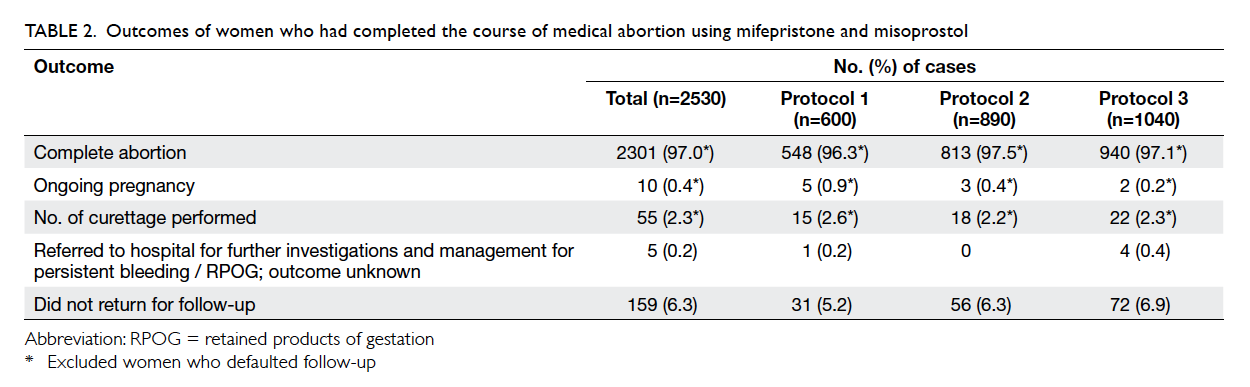

Minor side-effects that required treatment are

listed in Table 3. Treatment for allergic symptoms of

varying severity was required in 50 (2.0%) cases.

One woman developed back and neck rash after

mifepristone and was given oral chlorpheniramine

maleate 4 mg when she was admitted for

misoprostol. Another woman also reported skin

rash after mifepristone that resolved spontaneously

and no treatment was required. One or more of

the following minor allergic symptoms developed

in 94 women after misoprostol: palmar erythema,

palmar itchiness, perioral rash, and peri-orbital rash.

Symptoms resolved spontaneously in 51 women and

43 required oral chlorpheniramine maleate. Two

women received oral chlorpheniramine maleate

followed by intramuscular chlorpheniramine

maleate 10 mg because symptoms progressed: in

both cases a localised body rash progressed and

one woman became breathless. Three women

received intramuscular chlorpheniramine maleate:

one had generalised body rash with shortness of

breath, another had generalised facial rash, and

the third developed swollen lips and tongue and

palmar erythema with itchiness. One woman

developed peri-orbital rash with swelling and

blurred vision: intramuscular chlorpheniramine

maleate was administered. One hour later, her

vision normalised but peri-orbital rash with swelling

persisted. Symptoms gradually resolved following

intramuscular injection of hydrocortisone 100 mg.

During follow-up, 53 (2.1%) women

were treated with oral antibiotics for clinically

suspected pelvic infection—11 (1.8%) had received

vaginal misoprostol and 42 (2.2%) had sublingual

misoprostol (Table 3). Some were treated by their

private gynaecologists and others by doctors in

the Hospital Authority when they were admitted

for bleeding or abdominal pain. Those who were

treated by us during follow-up presented with pelvic

excitation tenderness with or without prolonged

spotting or bleeding. None of them had fever.

Empirical antibiotics were prescribed but no swabs

were taken for culture. Four (0.2%) cases of partial

mole were reported by the pathologist and these

women were referred to a specialist gynaecology

clinic of the Hospital Authority. Two women had

post-abortion anaemia due to prolonged bleeding for

over 4 weeks, with haemoglobin levels of 80 g/L and

86 g/L. In no case was bleeding sufficiently severe to

warrant transfusion, and there were no instances of

anaphylactic reaction, septicaemia, or death.

Following abortion, the three main

contraceptives of choice were male condom (38.1%),

combined oral contraceptive pill (36.2%), and

combined hormone injection (12.3%).

Discussion

When we first piloted the service, we adopted

the standard protocol of 200-mg oral mifepristone

plus 800-µg vaginal misoprostol. The side-effects,

complete abortion rate, and ongoing pregnancy

rate were as expected. After changing to sublingual

administration, the complete abortion rate was

similar and the ongoing pregnancy rate was halved

that of vaginal misoprostol. This was not a formal

study, hence women were not asked to record

the intensity of pain, diarrhoea, or discomfort.

Nonetheless, the incidence of side-effects for each

of the three protocols appears to be similar. Fewer

women treated according to protocol 3 required

pain relief but the underlying reasons are unclear.

The change from protocol 1 to 2 to 3 reduced the

ongoing pregnancy rate but the difference was not

statistically significant, probably because of the low

incidence of ongoing pregnancy. We are continuing

to use protocol 3 because it may achieve the best

clinical result without increasing patient discomfort.

Our nursing staff did not perceive any requirement

for increased patient care after changing to

sublingual misoprostol. Although one more dose of

misoprostol was given in protocol 3, this applied to

<10% of patients and did not adversely affect nursing

workload. In addition, auxiliary staff did not report

any increased need for cleaning after changing to

sublingual misoprostol. All patients, including those

treated with protocol 3, can be discharged before the

ward closes at 5 pm.

Unlike a research protocol, there is no time

limit for performing surgical curettage during follow-up

for incomplete medical abortion. Curettage is

recommended if a moderate amount of blood is

found in the vagina during speculum examination at

follow-up, when prolonged bleeding causes anaemia

or if tissue mass is present after 6 weeks. Patients

can also request curettage if persistent bleeding is

inconvenient.

Those who do not pass tissue mass after

misoprostol are followed up after 1 week with

routine pelvic ultrasound. Those with a live fetus, ie

ongoing pregnancy, will undergo suction evacuation.

Occasionally, a dead fetus is detected. During the

initial phase of service delivery, doctors arranged

curettage to remove the dead fetus. Our doctors

are accustomed to surgical abortion and hence

are anxious to clear any retained products. At our

case discussions, they are reassured that retained

products of gestation, even a dead fetus, is part of the

natural process of medical abortion and they can try

expectant management first. In most cases, watchful

waiting and subsequent follow-up 2 weeks later will

reveal that the fetus has gone. With the adoption

of protocol 3, the option of an additional dose of

misoprostol can be offered alongside expectant

management.

Collecting tissue mass passed and sending

it for pathological examination is important as a

partial mole cannot be diagnosed by ultrasound. The

incidence of partial mole is similar to that reported in

women undergoing surgical abortion in the FPAHK.

Follow-up is important because the failure rate for

medical abortion is higher than that for surgical

abortion, and misoprostol is potentially teratogenic.

The follow-up visits also provide an opportunity

to evaluate contraceptive use. To prevent further

unplanned pregnancies, contraceptive counselling

is provided at each visit. The consistent use of

contraceptive is emphasised and women are

encouraged to discuss any problems they experience

with contraception to maximise compliance.

Conclusion

A medical abortion service can be safely provided in

a non-hospital setting that also provides emergency

suction evacuation.

References

1. Medical management of first-trimester abortion.

Contraception 2014;89:148-61. Crossref

2. Medical abortion overview. Available from: http://gynuity.org/programs/more/overview/. Accessed 10 Dec 2014.

3. Pazol K, Creanga AA, Zane SB, Burley KD, Jamieson

DJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Abortion surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR

Surveill Summ 2012;61:1-44.

4. First trimester abortion guidelines and protocols.

International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2008.

5. Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health

systems. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

6. The care of women requesting induced abortion: evidence-based

clinical guideline No. 7. London: Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Press; 2011.

7. Kulier R, Kapp N, Gülmezoglu AM, Hofmeyr GJ, Cheng L,

Campana A. Medical methods for first trimester abortion.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(11):CD002855. Crossref

8. Raymond EG, Shannon C, Weaver MA, Winikoff B.

First-trimester medical abortion with mifepristone 200

mg and misoprostol: a systematic review. Contraception

2013;87:26-37. Crossref

9. Shannon C, Brothers LP, Philip NM, Winikoff B. Infection

after medical abortion: a review of the literature.

Contraception 2004;70:183-90. Crossref

10. Mifegyne. Physician leaflet. Exelgyn, France. HK-62757. 8

Apr 2014.