DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144306

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

A lucky and reversible cause of ‘ischaemic bowel’

YF Shea, MRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Felix CL Chow, MB, BS, MRCS2;

F Chan, MRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Janice JK Ip, MB, BS, FRCR3;

Patrick KC Chiu, FRCP(Glasg), FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Fion SY Chan, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)2;

LW Chu, MD, FRCP1

1 Acute Geriatric Unit, Grantham Hospital, Aberdeen, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong

Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

3 Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong

Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YF Shea (elphashea@gmail.com)

Abstract

An 81-year-old man was admitted with an infective

exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. He also had clinical and radiological features

suggestive of ileus. On day 6 after admission, he

developed generalised abdominal pain. Urgent

computed tomography of the abdomen showed

presence of portovenous gas and dilated small

bowel with pneumatosis intestinalis and whirl

sign. Emergency laparotomy was performed, which

showed a 7-mm perforated ulcer over the first part

of the duodenum and small bowel volvulus. Omental

patch repair and reduction of small bowel volvulus

were performed. No bowel resection was required.

The patient had a favourable outcome. Clinicians

should suspect small bowel volvulus as a cause of

ischaemic bowel. Presence of portovenous gas and

pneumatosis intestinalis are normally considered to

be signs of frank ischaemic bowel. The absence of

bowel ischaemia at laparotomy in this patient shows

that this is not necessarily the case and prompt

surgical treatment could potentially save the bowels

and lives of these patients.

Introduction

Ischaemic bowel is often associated with high

mortality. Common causes of ischaemic bowel

include atrial fibrillation with arterial embolism,

incarcerated hernia, volvulus, profound shock, and

vasculitis. Volvulus in adults most often occurs

in the colon and sigmoid colon (70-80%), and

less commonly in caecum (10-20%).1 Small bowel

volvulus (SBV) is rarely encountered in adults.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Intra-operatively, if gangrenous small bowel is found,

it needs to be resected and may potentially cause

long-term complications, including short bowel

syndrome.2 We report on a patient with primary SBV

associated with a perforated duodenal ulcer (PDU),

but the patient had a favourable outcome without

the need for bowel resection, thereby avoiding the

long-term complications associated with extensive

bowel resection.

Case report

In February 2014, an 81-year-old man was admitted

with an infective exacerbation of chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease caused by influenza B virus.

He had a history of left inguinal hernia repair. On

admission, he had a temperature of 38°C. He was

tachypnoeic with diffuse expiratory wheeze on chest

auscultation. His abdomen was slightly distended

and bowel sounds were sluggish. There was no

recurrence of the hernia. Complete blood count

showed leukocytosis (23.7 x 109 /L [reference range,

4.5-11.0 x 109 /L]) and a haemoglobin level of 109 g/L

(reference range, 140-175 g/L). Liver and renal

function tests and electrolytes were normal. Chest

radiograph showed hyperinflation of the lungs with

no consolidation. Abdominal radiograph showed

dilated small bowel without air-fluid level.

The patient was treated with inhaled

bronchodilators (albuterol 4 puffs every 4 hours

and ipratropium bromide 2 puffs every 4 hours) and

intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanate 1.2 g every 8

hours for 6 days. The dilated small bowel was initially

attributed to ileus and the patient was kept nil-by-mouth.

Daily abdominal radiograph did not reveal

any worsening of the small bowel dilatation. He

developed an episode of fast atrial fibrillation on day

2, which was controlled with amiodarone (initially

with intravenous loading and infusion, then followed

by 200 mg orally twice a day). Flatus and bowel

opening returned on day 5 and diet was resumed. On

day 6, the patient developed generalised abdominal

pain. His abdomen was distended with no localised

tenderness, but bowel sounds were absent. Arterial

blood gas showed no metabolic acidosis. Computed

tomography (CT) of the abdomen with contrast

showed presence of portovenous gas, dilated small

bowel with pneumatosis intestinalis, and whirl sign

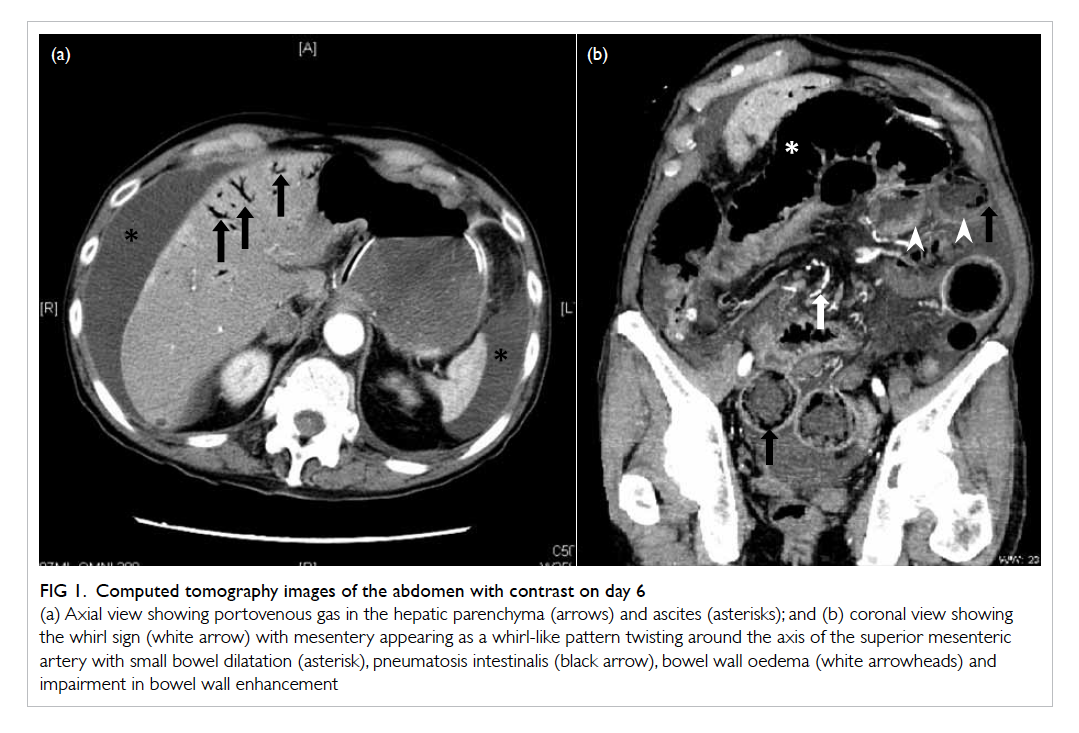

(Fig 1).

Figure 1. Computed tomography images of the abdomen with contrast on day 6

(a) Axial view showing portovenous gas in the hepatic parenchyma (arrows) and ascites (asterisk); and (b) coronal view showing the whirl sign (white arrow) with mesentery appearing as a whirl-like pattern twisting around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery with small bowel dilatation (asterisk), pneumatosis intestinalis (black arrow), bowel wall oedema (white arrowheads) and impairment in bowel wall enhancement

Emergency laparotomy was performed that

showed a 7-mm perforated ulcer over the first

part of the duodenum, which was sealed off by the

adjacent liver and falciform ligament. The small

bowel was grossly distended. There was SBV with

twisting of the small bowel along the root of the

mesentery by 180° with mild dusky appearance.

Omental patch repair of the duodenal ulcer and

reduction of the SBV were performed. Small bowel

perfusion improved significantly and a strong

superior mesenteric artery pulse was confirmed.

Bowel resection was not required. Histological

examination of the duodenal ulcer showed no

evidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Repeated

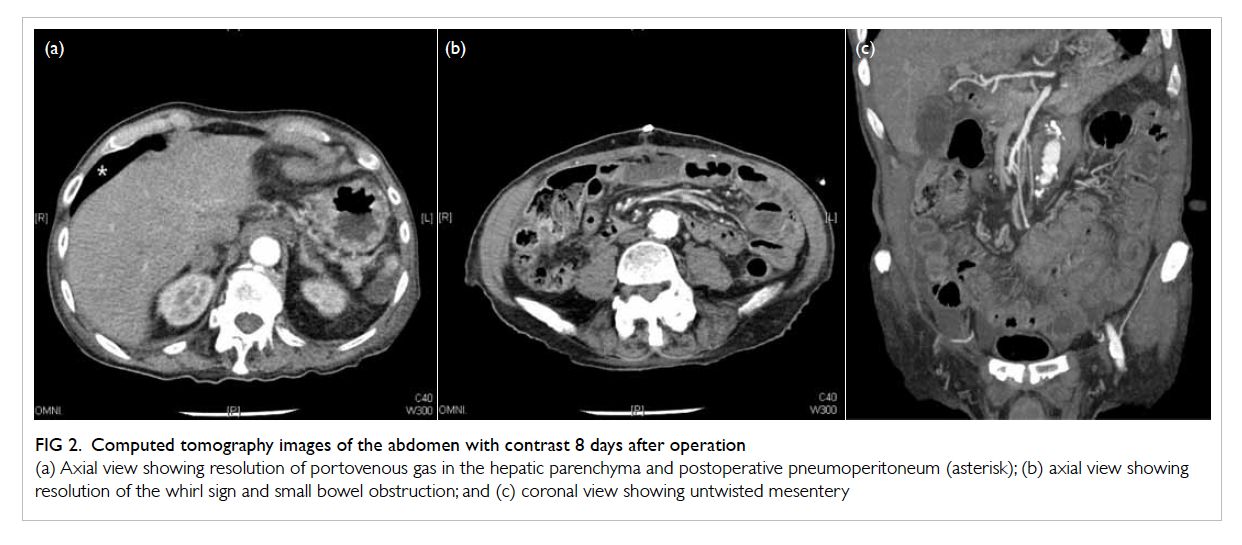

CT of the abdomen on day 8 showed resolution of

portovenous gas (Fig 2). Postoperatively, the patient

had the complication of an intra-abdominal abscess,

which was managed successfully by percutaneous

drainage and systemic antibiotics (vancomycin

500 mg daily and meropenem 1 g every 12 hours

intravenously for 2 weeks followed by levofloxacin

500 mg orally daily for 1 week). He was discharged

on day 36.

Figure 2. Computed tomography images of the abdomen with contrast 8 days after operation

(a) Axial view showing resolution of portovenous gas in the hepatic parenchyma and postoperative pneumoperitoneum (asterisk); (b) axial view showing resolution of the whirl sign and small bowel obstruction; and (c) coronal view showing untwisted mesentery

Discussion

The initial clinical feature of dilated small bowel

with sluggish bowel sound in the background of

an infective exacerbation of chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease was interpreted as being caused

by paralytic ileus.10 With the sudden worsening in

abdominal pain and the presence of paroxysmal

atrial fibrillation, the possibility of ischaemic

bowel was reconsidered. This explains why SBV

was only diagnosed by CT of the abdomen on day

6 after admission. Small bowel volvulus refers to

the twisting of a small bowel segment around the

axis of its own mesentery. In the elderly patients,

a secondary type with an underlying cause is

most commonly encountered.3 These secondary

causes include tumours, mesenteric lymph nodes,

adhesions after previous surgery, malrotation,

congenital bands, intussusception, colostomy, and

internal hernias.3 If no underlying cause is found, as

in this patient, the SBV is considered to be a primary

SBV (some surgeons may regard malrotation and

congenital adhesions as primary SBV).3 4 There are

certain risk factors that have been linked to primary

SBV, including long mobile mesentery, short

mesenteric base, long small bowel, and consumption

of a large amount of fibre-rich food after prolonged

fasting, with overloading of an empty intestine.1 3 6

With torsion of the small bowel and its mesentery,

the superior mesenteric arterial blood supply is

compromised, which results in bowel infarction that

usually occurs within 6 hours.3

The most important clinical feature is

persistent abdominal pain with absence of bowel

sounds on physical examination.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Plain abdominal

radiography is of limited diagnostic value.4

Abdominal CT is the most useful tool for obtaining

the correct preoperative diagnosis.4 The findings

on CT of the abdomen reflect the underlying

pathophysiology of the SBV. Whirl sign, which

refers to the twisting of mesentery around the

origin of the torsion, is the most typical radiological

sign of SBV.4 7 8 9 Alternatively, a venous cut-off sign,

referring to the occlusion of the superior mesenteric

vein, may also be found.9 With lymphatic and

venous occlusions, there will be small bowel wall

oedema and thickening.4 Small bowel dilatation is

caused by intestinal obstruction resulting from the

torsion.4 The bowel wall ischaemia results from the

pneumatosis intestinalis and portovenous gas.4 It has

been proposed that with intestinal ischaemia, the gas

produced by gas-forming organisms accumulates

in the bowel wall (pneumatosis intestinalis) and

circulates to the liver (portovenous gas); alternatively

the gas-producing organisms may enter the portal

circulation and produce the gas there (portovenous

gas).11

The causal relationship between SBV and

PDU in this patient is not well established. We

suspected that both the SBV and a non-PDU might

be present during the early phase of admission.

The resumption of a meal after a period of fasting

exacerbated the volvulus. It has been proposed that

the transit of food contents into the empty proximal

jejunum could cause a gravitational migration of this

segment into the left lower quadrant; forcing the

distal empty bowel loops in a clockwise direction

to the right upper quadrant with torsion of the

mesentery.6 The mechanical obstruction contributes

to the perforation of the duodenal ulcer which was a

weak point and, together with the impending bowel

ischaemia, led to the generalised abdominal pain.

The possibility of ileus converting into SBV was less

likely because of the usually reversible nature of ileus

with treatment of the infection.

A favourable outcome for patients with SBV

depends on prompt emergency laparotomy.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

The absence of bowel gangrene intra-operatively

predicted a favourable outcome for this patient.

Strictly, volvulus is defined by more than 180° of

rotation, so the intra-operative finding of small bowel

twisting around the mesentery root by 180° may

signify that the SBV was in the process of partially

reversing by itself. In one case series involving 19

patients, Ruiz-Tovar et al6 noted 100% mortality in

patients with an intra-operative finding of bowel

wall gangrene. Birnbaum et al3 also reported the use

of enteropexy to prevent recurrence of primary SBV

in a 69-year-old man with long mobile mesentery.

In summary, clinicians should suspect SBV as

a cause of ischaemic bowel. Presence of portovenous

gas and pneumatosis intestinalis are normally

considered signs of frank ischaemic bowel. The

absence of bowel infarction in this patient illustrates

that this is not necessarily the case and prompt

surgical treatment could potentially save the bowels

and lives of these patients.

References

1. Kim KH, Kim MC, Kim SH, Park KJ, Jung GJ. Laparoscopic

management of a primary small bowel volvulus: a case

report. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2007;17:335-8. Crossref

2. Rubio PA, Galloway RE. Complete jejunoileal necrosis due

to torsion of the superior mesenteric artery. South Med J

1990;83:1482-3. Crossref

3. Birnbaum DJ, Grègoire E, Campan P, Hardwigsen J, Le

Treut YP. Primary small bowel volvulus in adult. J Emerg

Med 2013;44:e329-30. Crossref

4. Jaramillo D, Raval B. CT diagnosis of primary small-bowel

volvulus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;147:941-2. Crossref

5. Weledji EP, Theophile N. Primary small bowel volvulus in

adults can be fatal: a report of two cases and brief review of

the subject. Trop Doct 2013;43:75-6. Crossref

6. Ruiz-Tovar J, Morales V, Sanjuanbenito A, Lobo E,

Martinez-Molina E. Volvulus of the small bowel in adults.

Am Surg 2009;75:1179-82.

7. Li CH, Chen CH, Chou JW. Intestinal obstruction caused

by small bowel volvulus. Am J Med 2011;124:e3-4. Crossref

8. Huang YM, Wu CC. Whirl sign in small bowel volvulus.

BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012:bcr2012006688.

9. Ho YC. “Venous cut-off sign” as an adjunct to the “whirl

sign” in recognizing acute small bowel volvulus via CT

scan. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:2005-6. Crossref

10. Batke M, Cappell MS. Adynamic ileus and acute colonic

pseudo-obstruction. Med Clin North Am 2008;92:649-70,ix. Crossref

11. Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, Doumit C. Hepatic

portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis

and treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:3585-90. Crossref