DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154626

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

MERS = SARS?

KL Hon, MD, FCCM

Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince

of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof KL Hon (ehon@cuhk.edu.hk)

To the Editor—In 2003, the World Health

Organization coined the word “SARS” for severe

acute respiratory syndrome in patients with a

relevant travel/contact history and severe acute

respiratory symptoms.1 2 3 In 2012, the definition

of SARS was not used when monitoring another

outbreak of illness with the same symptoms and

viral aetiology.3 4 5 Instead, the virus was termed the

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

(MERS-CoV) and “MERS” has since become the

official nomenclature for the epidemic.3 In May

2015, a South Korean man travelled to Huizhou after

first arriving in Hong Kong. His father had recently

returned from Bahrain and was confirmed to have

been infected with MERS. The case aroused panic

about an outbreak of MERS beyond the Middle East

in Korea, and possible outbreaks in Hong Kong and

Mainland China. Meanwhile, the Hong Kong media

colloquially referred to the MERS outbreak as the

“new SARS”, despite the new official nomenclature.

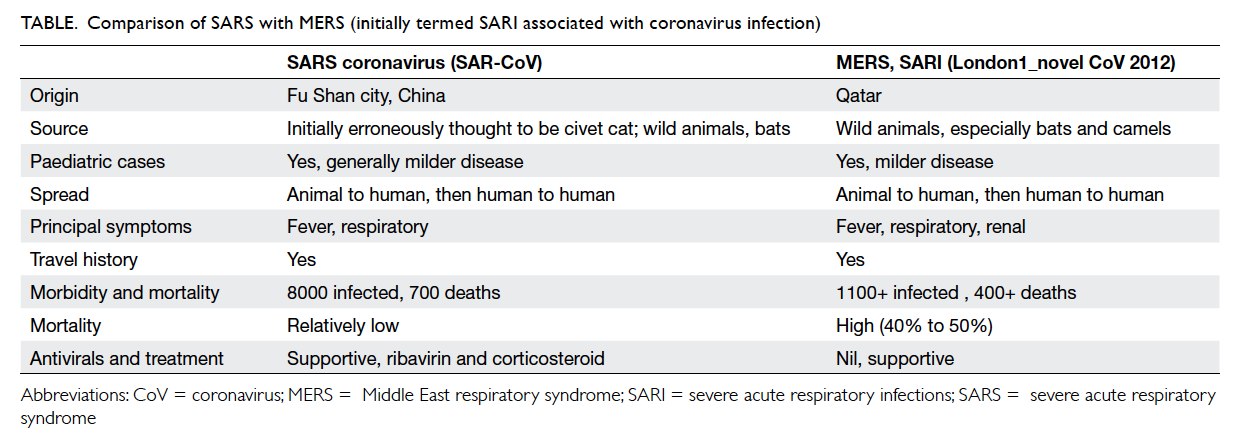

MERS = SARS?

MERS and SARS are the same syndrome in that

both are caused by coronavirus, and are associated

with fever, respiratory symptoms, and a relevant

travel history (Table).5 In other words, the severity,

acuteness, and respiratory syndrome in MERS is no

less severe than SARS. There is no need to create a

new name and abbreviation each time a coronavirus

emerges.

MERS ≠ SARS?

Some experts opine that MERS carries a higher

mortality, and there is a travel or contact history

linked with the Middle East.4 In 2012, the initial

patients with MERS had non-respiratory (renal)

involvement and the MERS-CoV differed to the

SARS-CoV. On this basis, MERS and SARS are not

the same.

Health organisations should provide consistent

definitions for index surveillance and epidemiological

and prognostication studies. They should

resist the temptation to introduce unnecessary new

terminology each time an outbreak of the same

severe respiratory infection occurs.2 Diagnosis of

emerging infections should be laboratory-based and

not clinical or ‘syndrome’-based.

References

1. Hon KL, Leung CW, Cheng WT, et al. Clinical presentations

and outcome of severe acute respiratory syndrome in

children. Lancet 2003;361:1701-3. Crossref

2. Hon KL, Li AM, Cheng FW, Leung TF, Ng PC. Personal

view of SARS: confusing definition, confusing diagnoses.

Lancet 2003;361:1984-5. Crossref

3. Hui DS, Memish ZA, Zumla A. Severe acute respiratory

syndrome vs. the Middle East respiratory syndrome. Curr

Opin Pulm Med 2014;20:233-41. Crossref

4. Zumla A, Hui DS, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory

syndrome. Lancet 2015 Jun 3. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

5. Hon KL. Severe respiratory syndromes: travel history

matters. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013;11:285-7. Crossref