Hong Kong Med J 2015 Oct;21(5):417–25 | Epub 28 Aug 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144472

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Patient acceptability, efficacy, and skin biophysiology of a cream and cleanser containing lipid complex with shea butter extract versus a ceramide product for eczema

KL Hon, MD, FCCM1; YC Tsang, BSc1; NH Pong, MPhil1; Vivian WY Lee, PharmD2;

NM Luk, FRCP3; CM Chow, FRCPCH1; TF Leung, FRCPCH, FAAAAI1

1 Department of Paediatrics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 School of Pharmacy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 Hong Kong Dermatology Foundation, Hong Kong

Full

paper in PDF

Full

paper in PDF

Corresponding author: Prof KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate patient acceptability,

efficacy, and skin biophysiological effects of a

cream/cleanser combination for childhood atopic

dermatitis.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Paediatric dermatology clinic at a university

teaching hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: Consecutive paediatric patients with

atopic dermatitis who were interested in trying a new

moisturiser were recruited between 1 April 2013 and

31 March 2014. Swabs and cultures from the right

antecubital fossa and the worst eczematous area,

disease severity (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index),

skin hydration, and transepidermal water loss were

obtained prior to and following 4-week usage of a

cream/cleanser containing lipid complex with shea

butter extract (Ezerra cream; Hoe Pharma, Petaling

Jaya, Malaysia). Global or general acceptability of

treatment was documented as ‘very good’, ‘good’,

‘fair’, or ‘poor’.

Results: A total of 34 patients with atopic dermatitis

were recruited; 74% reported ‘very good’ or ‘good’,

whereas 26% reported ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ general

acceptability of treatment of the Ezerra cream;

and 76% reported ‘very good’ or ‘good’, whereas

24% reported ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ general acceptability

of treatment of the Ezerra cleanser. There were

no intergroup differences in pre-usage clinical

parameters of age, objective SCORing Atopic

Dermatitis index, pruritus, sleep loss, skin hydration,

transepidermal water loss, topical corticosteroid

usage, oral antihistamine usage, or general

acceptability of treatment of the prior emollient.

Following use of the Ezerra cream, mean pruritus

score decreased from 6.7 to 6.0 (P=0.036) and mean

Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index improved

from 10.0 to 8.0 (P=0.021) in the ‘very good’/‘good’

group. There were no statistically significant

differences in the acceptability of wash (P=0.526)

and emollients (P=0.537) with pre-trial products.

When compared with the data of another ceramide-precursor

moisturiser in a previous study, there was

no statistical difference in efficacy and acceptability

between the two products.

Conclusions: The trial cream was acceptable in

three quarters of patients with atopic dermatitis.

Patients who accepted the cream had less pruritus

and improved quality of life than the non-accepting

patients following its usage. The cream containing

shea butter extract did not differ in acceptability or

efficacy from a ceramide-precursor product. Patient

acceptability is an important factor for treatment

efficacy. There is a general lack of published

clinical trials to document the efficacy and skin

biophysiological effects of many of the proprietary

moisturisers.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Patient acceptability is an important factor for treatment efficacy.

- There is a general lack of published clinical trials to document the efficacy and skin biophysiological effects of many of the proprietary moisturisers.

Introduction

Eczema or atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronically

relapsing dermatosis associated with atopy, and

characterised by reduced skin hydration (SH),

impaired skin integrity (transepidermal water

loss [TEWL]), and poor quality of life as a result

of deficient ceramides in the epidermis.1 Regular

application of a moisturiser is the key step in

its management. Moisturiser therapy for AD is

significantly complicated by the diversity of disease

manifestations and by a variety of complex immune

abnormalities.1 Filaggrin (filament-aggregating

protein) and related moisturising factors have an

important function in epidermal differentiation

and barrier function, and null mutations within the

filaggrin gene are major risk factors for developing

AD.2 3 4 5 6 Ceramides and related lipid products are also important components in skin barrier

function.7 Recent advances in the understanding

of the pathophysiological process of AD have led

to the production of new moisturisers targeted at

correcting the reduced amount of ceramides and

natural moisturising factors in the stratum corneum

with ceramides, pseudoceramides, or natural

moisturising factors.7 Many proprietary products

claim to have these ingredients, but have no or

limited studies to document their clinical efficacy.

Our group previously tested a number of these

commercial products and found patient preference

and acceptability may influence outcomes of

topical treatment independent of the ingredients

in these products.8 The purposes of this study were

to investigate patient acceptability of a cream/cleanser combination containing lipid complex and

shea butter extract with claimed antihistaminergic

properties, and evaluate its efficacy in improving

the clinical and biophysiological properties of the

skin in AD patients. A MEDLINE search was also

performed to evaluate whether evidence of efficacy

of many of the proprietary moisturisers exists.

Methods

Consecutive patients with AD who were interested

in trying a new moisturiser were recruited from

the paediatric dermatology clinic at a university

teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Diagnosis of AD

was based on the UK working group criteria.9 In

this study, SH and TEWL in the right forearm (2 cm

below the antecubital flexure), and disease severity

(SCORing Atopic Dermatitis [SCORAD] index)

were measured. We have previously described our

method of standardising measurements of SH and

TEWL.10 After acclimatisation in the consultation

room with the patient sitting comfortably in a chair

for 20 to 30 minutes, SH (in arbitrary units) and

TEWL (in g/m2/h) were then measured according

to the manufacturer’s instructions with the Mobile

Skin Center MSC 100 equipped with a Corneometer

CM 825 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH,

Cologne, Germany), and a Tewameter TM 210

probe (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH).

We documented that a site 2 cm distal to the right

antecubital flexure was optimal for standardisation.

Oozing and infected areas were avoided by moving

the probe slightly sideways.10 The clinical severity of

AD was assessed with the SCORAD index.11 12 The SCORAD index also scores pruritus and sleep loss/disturbance on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being not affected

and 10 being most severely affected).

Patients were given a liberal supply of a trial

cream containing lipid complex with shea butter

extract for eczema (Ezerra [E]; Hoe Pharma, Petaling

Jaya, Malaysia) and body wash (E, Hoe Pharma). The

moisturiser contained STIMU-TEX AS (Centerchem

Inc, Norwalk [CT], US) and saccharide isomerate. The

wash contained STIMU-TEX AS and Amisoft (Amisoft

Technologies Ltd, Brentwood, UK). The patients

were instructed not to use any other moisturiser

or topical treatment. Use of any medications such

as topical corticosteroid or oral antihistamine was

documented. Patients were encouraged to use the

test moisturiser at least twice daily on the flexures

and areas with eczema. In case the emollient effect

was not satisfactory, they could use their usual

emollient and medications, but the frequency of

such use was to be reported and they must continue

with the E moisturiser. The patients were reviewed

at the end of 4 weeks. Measurements of SCORAD

index, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index

(CDLQI), SH, and TEWL were repeated. Patients’

global or general acceptability of treatment (GAT)

was recorded as ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, or ‘poor’.8 13 Approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong

Kong and written informed consents were obtained

from the guardian and patient.

Continuous data were expressed as mean

and standard deviation. Mann-Whitney U test was

used for intergroup comparison and Wilcoxon

signed rank test for within-group comparison as a

small number of patients was included. Categorical

data were presented in counts. Chi squared test

or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate was used

to compare intergroup categorical data, while

McNemar’s test was used to compare within-group

categorical data. Fisher’s exact test was

used to determine the GAT of previously used

proprietary products and E moisturiser and wash.

All comparisons were two-tailed, and P values of

<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

The results were also compared with the data for an

emollient (C) containing ceramide-precursor lipids

and moisturising factors (n=24).14

Results

Between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014, 34 patients

(56% boys; mean [± standard deviation] age, 12.1 ± 4.4 years) with AD were recruited and treated with applications of a moisturising cream (E). Compliance

was good and patients generally managed to use

the moisturiser daily. Among the patients, 74%

reported ‘very good’ or ‘good’ acceptability, whereas

26% reported ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ acceptability of the

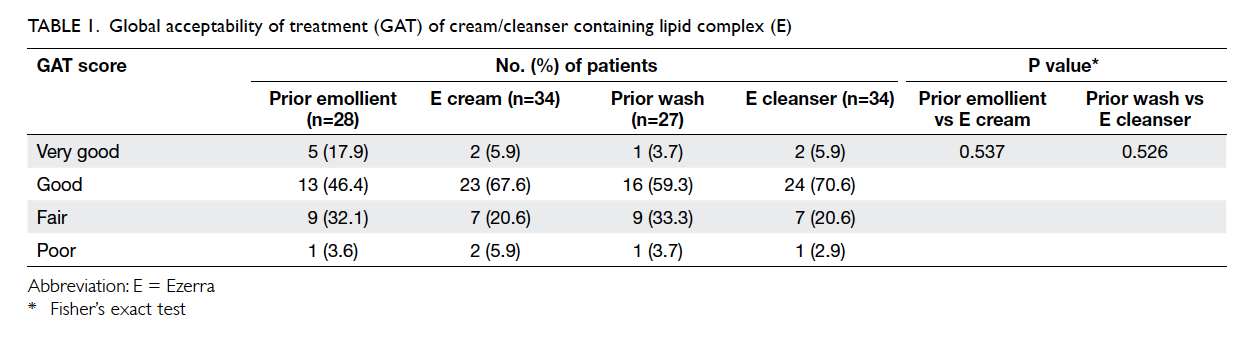

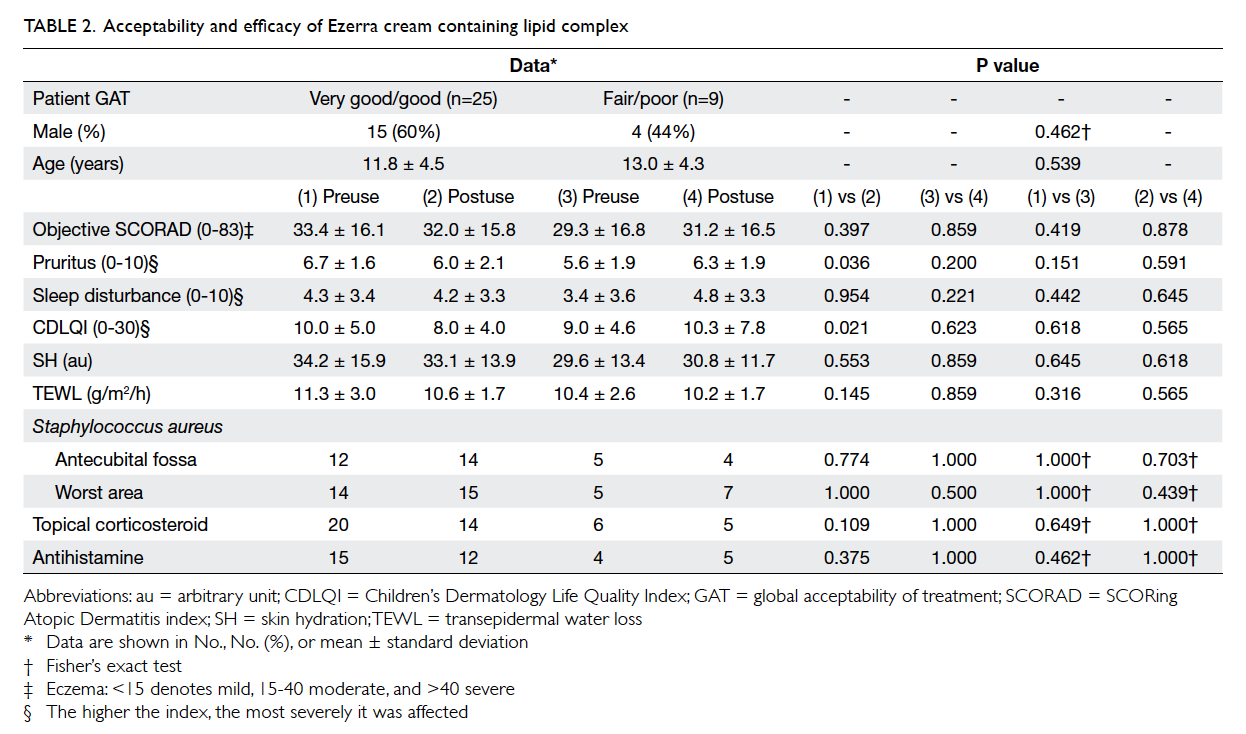

moisturiser (Tables 1 and 2).

There were no intergroup differences in pre-usage

clinical parameters of age, objective SCORAD

index, pruritus, sleep loss, SH, TEWL, topical

corticosteroid usage, oral antihistamine usage, or

GAT of prior emollient (Table 2). Following

use of the E cream, pruritus score and CDLQI were lower

in the ‘very good’/‘good’ group than in the ‘fair’/‘poor’

group. Mean pruritus score decreased from 6.7 to 6.0

(P=0.036) and mean CDLQI improved from 10.0 to

8.0 (P=0.021) in the ‘very good’/‘good’ group (Table 2).

When analysed for the association of the

rating of acceptability, the acceptability of E

cleanser (P=0.526) and E cream (P=0.537) was not

significantly associated with their respective pre-trial

products (Table 1). Patients who preferred the trial moisturiser or wash might or might not have

come from the group of poor/fair acceptability of

their prior emollient or wash, and vice versa. Prior

products included emulsifying ointment and various

other proprietary products.

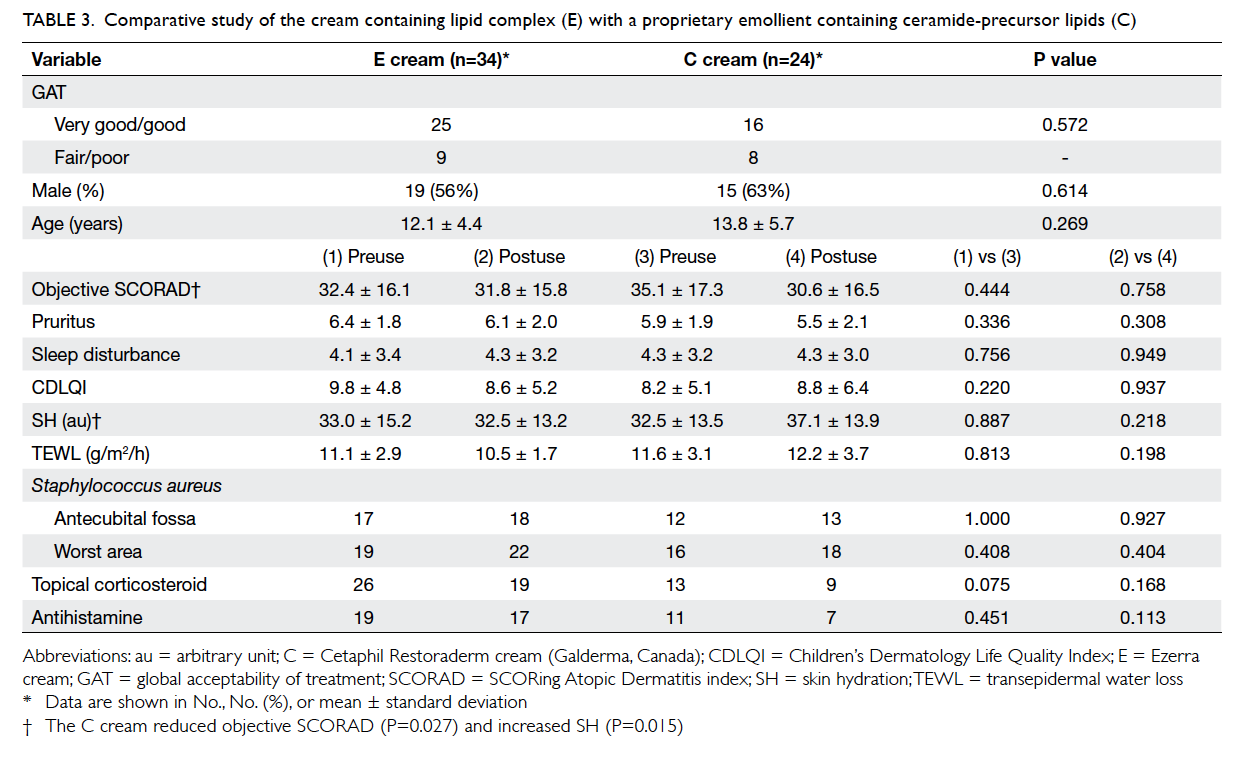

When compared historically with another

product containing ceramide-precursor lipids (C)

that we tested in a previous report,14 the present shea

butter extract–containing cream showed similar

efficacy and acceptability (Table 3). It appears that

ceramide does not confer superiority in terms of

acceptability and clinical efficacy.

Table 3. Comparative study of the cream containing lipid complex (E) with a proprietary emollient containing ceramide-precursor lipids (C)

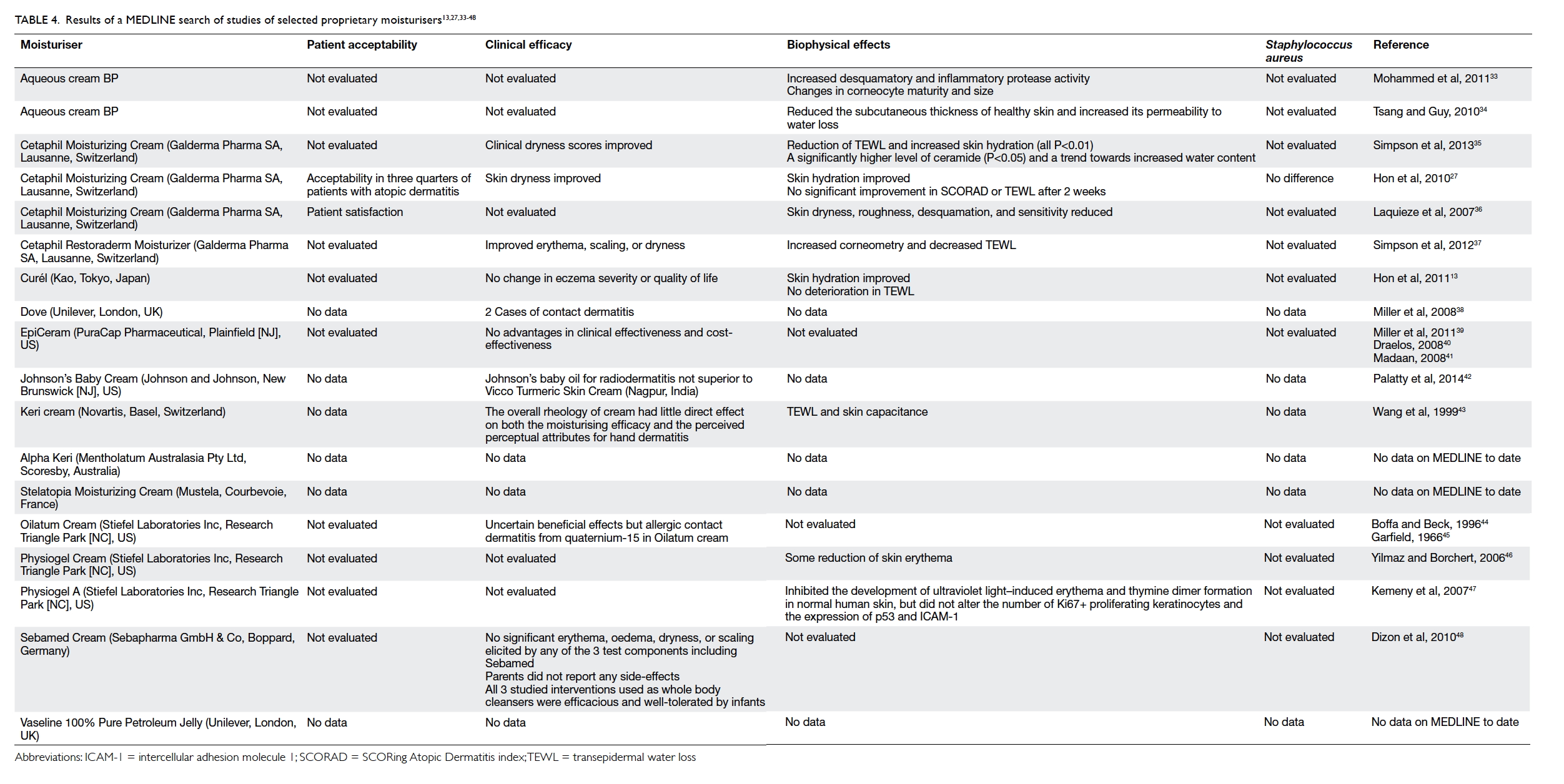

A MEDLINE search was performed on selected

common proprietary moisturisers/emollients

for eczema using the following search terms in

combinations: “eczema” OR “atopic dermatitis”,

AND “emollient” OR “moisturizer” OR “barrier” OR

“barrier repair” OR “natural moisturizing factor”

OR “ceramide” OR “pseudoceramide”. We selected

literature mainly from the past 10 years, but did not

exclude commonly referenced and highly cited older

articles. We included and described all randomised

trials, case series, and bench studies in barrier repair

therapy for eczema, with limits activated (Humans,

Clinical Trial, Meta-Analysis, Randomized

Controlled Trial, English, published in the past 10

years). Editorials, letters, practice guidelines, reviews,

and animal studies were excluded. In addition, the

bibliographies of the retrieved articles and our own

research database were also hand searched. As of

23 April 2014, 18 articles were obtained (Table

413 27 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48). The common proprietary moisturisers

were included. The publications generally provided

limited evidence of efficacy and biophysical effects

(such as SH and TEWL), but virtually no data on

patient acceptability and effects on Staphylococcus

aureus colonisation.

Table 4. Results of a MEDLINE search of studies of selected proprietary moisturisers13 27 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48

Discussion

Atopic dermatitis is a chronically relapsing

dermatosis characterised by pruritus, skin dryness,

inflammation, secondary bacterial infection by S

aureus, and poor quality of life.1 15 16 17 The stratum

corneum normally consists of fully differentiated

corneocytes surrounded by natural moisturising

factor and a lipid-rich matrix containing cholesterol,

free fatty acids, and ceramide. In AD, metabolism

of lipid and filaggrin protein is abnormal, causing

a deficiency of ceramide and natural moisturising

factors and impairment of epidermal barrier

function that leads to increased TEWL and

abnormal skin integrity.1 4 7 18 19 20 21 Moisturisers form

the first-line therapy as maintenance and therapeutic

management in childhood-onset AD.1 22 23 Hydration

of the skin helps to improve dryness, reduce pruritus,

and restore disturbed barrier function. Bathing

without the use of moisturiser may compromise

SH.24 25 26

In this study, we explored clinical efficacy

and acceptability of a proprietary moisturiser (E)

containing shea butter extract. The cream was

acceptable as ‘very good’ or ‘good’ in about three quarters

of patients with AD who tried the moisturiser,

and ameliorated their pruritus and improved their

quality of life.

Compliance or adherence to usage of the

moisturising cream was reflected by the GAT and

reported frequency of usage (times per day).27 We

did not calculate the amount of moisturising cream

used because many parents/patients have discarded

the tubes or failed to bring them back for weighing

in previous trials. Topical steroid usage is also an

important confounding factor in this study. We

standardise treatment for all our patients by not

changing their existing topical steroid (mometasone

furoate) and other medications (ie oral antihistamine,

topical immunomodulant, and Chinese medicine).

In previous studies, we found that documentation

of the exact amount of steroid usage (weight or

frequency of usage) was difficult for similar reasons

as those for moisturisers.28 Most parents are still

concerned about topical steroid usage and tend to

use the minimal amount of steroid as far as possible.29

Alternative explanations for the modest

within-group changes in pruritus and CDLQI

(Table 2) include regression to the mean, detection

bias, or confounding by co-treatment with topical

corticosteroid or usual emollients. Our study did not

demonstrate any reduction in clinical severity or S

aureus colonisation. When compared historically

with another product (C) containing ceramide-precursor lipids that we tested in a previous report,14

although different patients were involved and the E

or C products were not received by patients in the

same period, the present E cream showed similar

efficacy and acceptability with the use of a similar

study protocol as the previous study. It appears that

specific ceramide-precursor lipids do not confer

superiority in terms of acceptability and clinical

efficacy.

Regarding intra-group comparisons, the C

cream reduced objective SCORAD index (P=0.027)

and increased SH (P=0.015), whereas the E cream

reduced pruritus and improved CDLQI only in the

‘very good’/‘good’ group (Table 3). Regarding intergroup

comparisons, overall there were no significant

differences between the pretreatment and post-treatment

parameters for the two moisturisers. We

note that in the subgroup analysis, pruritus and

CDLQI could be the possible contributing factors

for the acceptability in the ‘very good’/‘good’

group for the E cream.

Many proprietary emollients/moisturisers are

available in the market.7 22 30 31 Despite claims about

their efficacy, little evidence has demonstrated the

short- or long-term usefulness of many of these

proprietary products. Ceramides, pseudoceramides,

or filaggrin protein products have been studied

and added to commercial moisturisers to mimic

natural skin lipids and moisturising factors.32

Anxious parents often consult their physicians for

recommendation as to the choice of an ideal or perfect

moisturiser for their child with AD. Physicians need

to have some evidence-based understanding about

these moisturisers in order to address issues raised

by the parents. We performed a MEDLINE search

and found that only a few of these products have

published clinical data (Table 413 27 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48). The majority either do not have patient acceptability or clinical

efficacy data in the scientific literature. The efficacy

of ceramides and natural moisturiser factors is

generally not scientifically documented. Larger-scale,

properly conducted randomised controlled trials

with recruitment of more study participants may

validate subtle differences in clinical efficacy between

different emollients. It is likely that there will be

similar outcomes in efficacy if the tested emollient is

compared with any other traditional emollient such

as aqueous cream or Vaseline (Unilever, London,

England). Commercial pharmaceutical companies

are often unwilling to supply free samples of their

product to compare with an inexpensive product,

even if more validated and conclusive results

may be obtained by increasing the sample size in

clinical trials. That is perhaps why there are so few

comparative clinical studies in the medical literature.

In a wider context, AD is a complex multifactorial

atopic disease. Monotherapy targeting merely at

replacement of ceramides, pseudoceramides, or

filaggrin degradation products at the epidermis is

often suboptimal. In particular, colonisation with S

aureus must be adequately treated before emollient

treatment can be optimised.17

The major hindrance to the efficacy of a

moisturiser is the patient’s perception as to what

an ideal moisturiser should be.8 Indeed, it is often

not the product, but the patient’s acceptability that

determines whether it may be used consistently.

Therefore, the physician caring for a patient with AD

must educate and guide the parents and the patient

to choose the most acceptable formulation to ensure

optimal compliance.

This open-label series confirms our previous

experience in emollient research. First, patient

acceptance of the strengths, types, and formulations

of any novel products need to be studied, preferably

in randomised controlled trials. Second, holistic

efficacy studies of all clinical parameters (namely

severity scores, quality-of-life indices, SH, TEWL,

S aureus colonisation, and patient acceptance) must

be included. Third, as AD is not a simple epidermal

skin disease but rather a complex atopic disease,

emollient alone is bound to be suboptimal in efficacy.

Conclusions

Well-designed, large-scale, randomised, placebo-controlled

trials to document therapeutic effects on

disease severity, skin biophysiological parameters,

quality of life, and patient acceptability are needed.

Patient’s acceptability of a certain product is pivotal

for compliance and clinical outcome. Only few of

the many proprietary moisturisers for AD have

undergone clinical trials to evaluate clinical efficacy

and patient acceptability.

Declaration

Drs KL Hon and TF Leung have performed research

on eczema therapeutics, and written about the

subject matter of filaggrin, ceramides, and emollients.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hoe Pharma in Hong Kong for freely

supplying the studied materials. The company,

however, was not involved in the design or analysis of

the research data. The products used in the present

study could be examples of other similar products

containing shea butter.

References

1. Leung AK, Hon KL, Robson WL. Atopic dermatitis. Adv

Pediatr 2007;54:241-73. Crossref

2. Sandilands A, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Hull PR, et al.

Comprehensive analysis of the gene encoding filaggrin

uncovers prevalent and rare mutations in ichthyosis

vulgaris and atopic eczema. Nat Genet 2007;39:650-4. Crossref

3. Sandilands A, Smith FJ, Irvine AD, McLean WH. Filaggrin’s

fuller figure: a glimpse into the genetic architecture of

atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:1282-4. Crossref

4. Enomoto H, Hirata K, Otsuka K, et al. Filaggrin null

mutations are associated with atopic dermatitis and

elevated levels of IgE in the Japanese population: a family

and case-control study. J Hum Genet 2008;53:615-21. Crossref

5. Chamlin SL, Kao J, Frieden IJ, et al. Ceramide-dominant

barrier repair lipids alleviate childhood atopic dermatitis:

changes in barrier function provide a sensitive indicator of

disease activity. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:198-208. Crossref

6. Maintz L, Novak N. Getting more and more complex:

the pathophysiology of atopic eczema. Eur J Dermatol

2007;17:267-83.

7. Hon KL, Leung AK. Use of ceramides and related products

for childhood-onset eczema. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy

Drug Discov 2013;7:12-9. Crossref

8. Hon KL, Wang SS, Pong NH, Leung TF. The ideal

moisturizer: a survey of parental expectations and practice

in childhood-onset eczema. J Dermatolog Treat 2013;24:7-12. Crossref

9. Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. The U.K.

Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis.

III. Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol

1994;131:406-16. Crossref

10. Hon KL, Wong KY, Leung TF, Chow CM, Ng PC.

Comparison of skin hydration evaluation sites and

correlations among skin hydration, transepidermal water

loss, SCORAD index, Nottingham Eczema Severity Score,

and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J

Clin Dermatol 2008;9:45-50. Crossref

11. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index.

Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic

Dermatitis. Dermatology 1993;186:23-31. Crossref

12. Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labreze L, Stalder JF, Ring J, Taieb A.

Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index:

consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic

Dermatitis. Dermatology 1997;195:10-9. Crossref

13. Hon KL, Wang SS, Lau Z, et al. Pseudoceramide for

childhood eczema: does it work? Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:132-6.

14. Hon KL, Pong NH, Wang SS, Lee VW, Luk NM, Leung

TF. Acceptability and efficacy of an emollient containing

ceramide-precursor lipids and moisturizing factors

for atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients. Drugs R D

2013;13:37-42. Crossref

15. Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD, Nomura I, Hamid

QA. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest

2004;113:651-7. Crossref

16. Hon KL, Lam MC, Leung TF, et al. Clinical features

associated with nasal Staphylococcus aureus colonisation

in Chinese children with moderate-to-severe atopic

dermatitis. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:602-5.

17. Hon KL, Wang SS, Lee KK, Lee VW, Fan LT, Ip M.

Combined antibiotic/corticosteroid cream in the empirical

treatment of moderate to severe eczema: friend or foe? J

Drugs Dermatol 2012;11:861-4.

18. Hanifin JM, Rajka RG. Diagnostic features of atopic

dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1980;2:44-7.

19. Hanifin JM. Atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol

1982;6:1-13. Crossref

20. Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope:

a model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol

2005;6:328-40. Crossref

21. Leung DY, Nicklas RA, Li JT, et al. Disease management

of atopic dermatitis: an updated practice parameter. Joint

Task Force on Practice Parameters. Ann Allergy Asthma

Immunol 2004;93(3 Suppl 2):S1-21. Crossref

22. Hon KL, Leung AK, Barankin B. Barrier repair therapy

in atopic dermatitis: an overview. Am J Clin Dermatol

2013;14:389-99. Crossref

23. Krakowski AC, Eichenfield LF, Dohil MA. Management

of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Pediatrics

2008;122:812-24. Crossref

24. Lancaster W. Atopic eczema in infants and children.

Community Pract 2009;82:36-7.

25. Tarr A, Iheanacho I. Should we use bath emollients for

atopic eczema? BMJ 2009;339:b4273. Crossref

26. Hon KL, Leung TF, Wong Y, So HK, Li AM, Fok TF. A

survey of bathing and showering practices in children with

atopic eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:351-4. Crossref

27. Hon KL, Ching GK, Leung TF, Choi CY, Lee KK, Ng PC.

Estimating emollient usage in patients with eczema. Clin

Exp Dermatol 2010;35:22-6. Crossref

28. Hon KL, Leung TF, Ng PC, et al. Efficacy and tolerability

of a Chinese herbal medicine concoction for treatment of atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:357-63. Crossref

29. Hon KL, Kam WY, Leung TF, et al. Steroid fears in children

with eczema. Acta Paediatr 2006;95:1451-5. Crossref

30. Roos TC, Geuer S, Roos S, Brost H. Recent advances

in treatment strategies for atopic dermatitis. Drugs 2004;64:2639-66. Crossref

31. Baumer JH. Atopic eczema in children, NICE. Arch Dis

Child Educ Pract Ed 2008;93:93-7.

32. Park KY, Kim DH, Jeong MS, Li K, Seo SJ. Changes of

antimicrobial peptides and transepidermal water loss after

topical application of tacrolimus and ceramide-dominant

emollient in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Korean Med

Sci 2010;25:766-71. Crossref

33. Mohammed D, Matts PJ, Hadgraft J, Lane ME. Influence of Aqueous Cream BP on corneocyte size, maturity, skin protease activity, protein content and transepidermal water loss. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:1304-10. Crossref

34. Tsang M, Guy RH. Effect of Aqueous Cream BP on human

stratum corneum in vivo. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:954-8. Crossref

35. Simpson E, Böhling A, Bielfeldt S, Bosc C, Kerrouche N.

Improvement of skin barrier function in atopic dermatitis patients with a new moisturizer containing a ceramide

precursor. J Dermatolog Treat 2013;24:122-5. Crossref

36. Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat

2007;18:158-62. Crossref

37. Simpson E, Trookman NS, Rizer RL, et al. Safety and tolerability of a body wash and moisturizer when applied to infants and toddlers with a history of atopic dermatitis:

results from an open-label study. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:590-7. Crossref

38. Miller MA, Borys D, Riggins M, Masneri DC, Levsky ME. Two cases of contact dermatitis resulting from use of body wash as a skin moisturizer. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:246.e1-2.

39. Miller DW, Koch SB, Yentzer BA, et al. An over-the-counter

moisturizer is as clinically effective as, and

more cost-effective than, prescription barrier creams

in the treatment of children with mild-to-moderate

atopic dermatitis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Drugs

Dermatol 2011;10:531-7.

40. Draelos ZD. The effect of ceramide-containing skin care

products on eczema resolution duration. Cutis 2008;81:87-91.

41. Madaan A. Epiceram for the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Drugs Today (Barc) 2008;44:751-5. Crossref

42. Palatty PL, Azmidah A, Rao S, et al. Topical application

of sandal wood oil and turmeric based cream prevents radiodermatitis in head and neck cancer patients

undergoing external beam radiotherapy: a pilot study. Br J Radiol 2014;87:20130490. Crossref

43. Wang S, Kislalioglu MS, Breuer M. The effect of rheological

properties of experimental moisturizing creams/lotions on

their efficacy and perceptual attributes. Int J Cosmet Sci

1999;21:167-88. Crossref

44. Boffa MJ, Beck MH. Allergic contact dermatitis from

quaternium 15 in Oilatum cream. Contact Dermatitis

1996;35:45-6. Crossref

45. Garfield SS. The beneficial effects of oilatum cream on

hyperhydrosis. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1966;56:22-4. Crossref

46. Yilmaz E, Borchert HH. Effect of lipid-containing, positively

charged nanoemulsions on skin hydration, elasticity and

erythema—an in vivo study. Int J Pharm 2006;307:232-8. Crossref

47. Kemeny L, Koreck A, Kis K, et al. Endogenous phospholipid

metabolite containing topical product inhibits ultraviolet light–induced inflammation and DNA damage in human

skin. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2007;20:155-61. Crossref

48. Dizon MV, Galzote C, Estanislao R, Mathew N, Sarkar

R. Tolerance of baby cleansers in infants: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr 2010;47:959-63. Crossref