DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144312

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Clozapine-induced acute interstitial nephritis

SY Chan, MRCP (UK), FHKCP1;

CY Cheung, PhD, FHKCP1;

PT Chan, MB, BS, FHKCPath2;

KF Chau, FHKCP, FRCP (Lond)1

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SY Chan (helenchansy@gmail.com)

Abstract

Acute interstitial nephritis is a common cause of

acute kidney injury. Acute interstitial nephritis is

most commonly induced by drug although the cause

may also be infective, autoimmune, or idiopathic.

Although eosinophilia and eosinophiluria may help

identify this disease entity, the gold standard for

diagnosis remains renal biopsy. Prompt diagnosis

is important because discontinuation of the culprit

drugs can reduce further kidney injury. We present a

patient with an underlying psychiatric disorder who

was subsequently diagnosed with clozapine-induced

acute interstitial nephritis. Monitoring of renal

function during clozapine therapy is recommended

for early recognition of this rare side-effect.

Case report

A 29-year-old woman with a known history

of bipolar affective disorder and paranoid

schizophrenia admitted to our hospital because of

relapse of psychiatric symptoms in June 2011. She

had no significant medical illness. Her medication

included quetiapine fumarate and sodium valproate

but was changed to haloperidol decanoate depot

injection, trihexyphenidyl, and clozapine following

hospitalisation. Clozapine was commenced at 50 mg

once per day and gradually stepped up to 400 mg once

per day. One week later she developed fever but had

no respiratory or urinary symptoms. She remained

conscious and alert with stable vital signs. Physical

examination revealed no significant abnormality and

preliminary investigations showed normochromic

and normocytic anaemia with haemoglobin level of

87 g/L, white cell count of 11.8 x 109 /L (eosinophils

15.1%; absolute count 2.3 x 109 /L), and serum

creatinine of 229 µmol/L (baseline serum creatinine

1 week ago, 39 µmol/L). Her liver enzymes, lactate

dehydrogenase, and haptoglobin were all within

normal range. Chest radiograph showed clear

lung fields. She was empirically given amoxicillin/clavulanic acid but treatment was complicated by

gastro-intestinal side-effects such as vomiting and

diarrhoea. The antibiotics were stopped immediately

and the symptoms subsided. Clozapine was further

titrated up to 700 mg once per day with consequent

improvement in her mental state. Nonetheless,

fever persisted with further deterioration in renal

function (serum creatinine rose to 356 µmol/L).

Autoimmune markers including anti–nuclear

antibody, anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies,

and anti–glomerular basement membrane antibody

were all within normal range. Urinalysis revealed

the presence of red blood cells and eosinophils

but urine culture showed no bacterial growth. The

24-hour urine protein was 1.18 g. Ultrasound of the

urinary system showed normal-sized kidneys with

no hydronephrosis. Ultrasound-guided renal biopsy

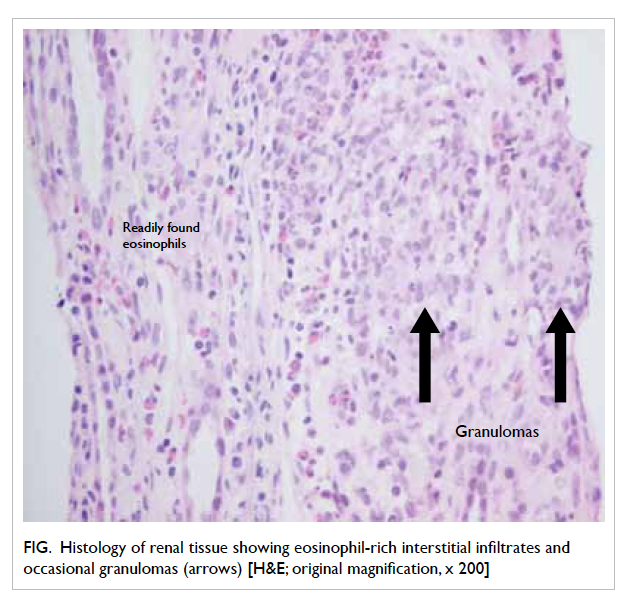

was performed and the histology showed features

of tubulointerstitial nephritis with eosinophil-rich

interstitial infiltrates and occasional granulomas

(Fig). The likely diagnosis was drug-induced acute

interstitial nephritis (AIN). Clozapine was withheld,

fever subsided afterwards and renal function

gradually returned to normal 4 weeks following

cessation of clozapine.

Figure. Histology of renal tissue showing eosinophil-rich interstitial infiltrates and occasional granulomas (arrows) [H&E; original magnification, x 200]

Discussion

Drug-induced AIN is not uncommon. Common

nephrotoxic drugs include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics such

as aminoglycosides and vancomycin. Although

amoxicillin/clavulanic acid remains a possible culprit

in this case for AIN, the short duration of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid use and sequence of events are more

suggestive of clozapine-induced AIN.

Acute interstitial nephritis is defined as an

immune-mediated condition characterised by

the presence of inflammation and oedema in the

tubulointerstitium of the kidneys. It accounts for

15% to 27% of biopsy-proven acute kidney injury.

Acute interstitial nephritis is most commonly

drug-induced although the cause may also be

infective, autoimmune, or idiopathic.1 2 3 4 5 The classic triad—fever, skin rash, and eosinophilia—is only

present in 5% to 10% of patients with AIN.2 3 4 5 As a

result, a high level of clinical suspicion is essential

since around 40% of patients with AIN eventually

required dialysis.2 A detailed drug history, especially

herbal medicine which is common in our locality,

recreational drugs and radio-contrast, are important

for diagnosis. Other history including water

exposure and animal contact (pets or stray animals)

can help exclude or confirm several infective causes

such as Legionnaires’ disease and leptospirosis.

Systemic manifestations of vasculitis should also be

specifically looked for during physical examination.

There are no specific signs and symptoms to

differentiate drug-induced AIN from other causes of

AIN. Fever is present in around 30% of patients with

drug-induced AIN3 5 and it typically occurs within 2 weeks of initiation of a new drug.3 Skin rash, usually

of morbilliform or maculopapular appearance, is

found in only 15% to 50% of patients, depending on

the type of medication.3 5 One retrospective review showed that around 45% of patients have arthralgia,

and 15% and 21% of patients have dysuria and loin

pain, respectively.5 Eosinophilia is thought to have

great diagnostic value in drug-induced AIN as it

signifies a hypersensitivity reaction although the

degree and frequency of eosinophilia vary with

different medications.4 Methicillin-induced AIN is

associated with eosinophilia in 80% of cases while

AIN due to NSAID is less commonly associated

with eosinophilia, which is only around 35% of

cases.4 However, the presence of eosinophilia can

also be found in infections, especially those caused

by helminths, allergic diseases such as asthma

and eczema, and even malignant conditions such

as lymphoma and carcinoma of the colon. Like

eosinophilia, the presence of eosinophiluria is neither

sensitive nor specific for drug-induced AIN. The

sensitivity ranges from 63% to 91%, and specificity

from 52% to 94%.3 4 Other conditions such as lower urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, prostatitis,

acute tubular necrosis, glomerulonephritis,

and urinary schistosomiasis can also result in

eosinophiluria.3 Other parameters from urine

samples may also provide clues for drug-induced

AIN. Proteinuria is present in 93% of patients but

only 2.5% have a nephrotic range of proteinuria.2

Haematuria is usually microscopic and is present in

60% to 80% of cases while gross haematuria is only

present in 5% of patients.2 Renal biopsy can confirm

the diagnosis of AIN by demonstrating inflammation

and oedema of the renal interstitium and tubulitis.2 3 4 5

The presence of a considerable number of eosinophils

in the interstitium will point to a diagnosis of drug-induced

AIN, while an abundance of neutrophils is

suggestive of an infective cause.3

As drug-induced AIN is idiosyncratic and

not dose-dependent, the mainstay of treatment is

cessation of the causative agents. Nonetheless, not

all patients experience complete recovery despite

withdrawal of the index medication. Neither the

severity of renal failure, the extent of interstitial

involvement (including fibrosis), nor the severity

of tubulitis predicts the clinical outcome.2 3 4 5 More

established prognostic factors are the duration

of renal failure and creatinine level 6 to 8 weeks

after diagnosis.4 Some studies advocate the use

of corticosteroid to hasten recovery and prevent

progression to chronic kidney disease6 but these

studies have usually been small and retrospective.2 3 4

Since 1999, 10 cases of clozapine-induced AIN

have been described.6 7 8 Among these patients, the

ages ranged from 24 to 69 years, and six were male.

In patients who presented within 2 weeks of commencing

clozapine, 80% exhibited a hypersensitivity

reaction. In those who presented late, symptoms

developed up to 3 months after starting clozapine.

Fever was present in 80% but, surprisingly, none

reported skin rash or arthralgia. Proteinuria was

detected in 80% of cases, but only four patients

had red blood cells in the urine. Eosinophilia was

present in half of the patients only. Four patients

had the diagnosis of AIN confirmed by histology.

A phenomenon is observed wherein the effect of

clozapine on the kidney can be potentiated by the

concomitant use of antibiotics, especially those

that are known to have higher risks of interstitial

damage, such as the penicillin derivatives.6 In our

patient, the temporal relationship between the

initiation of clozapine and the development of acute

kidney injury matched the time frame described

in the literature. In addition, the presence of fever,

eosinophilia, and eosinophiluria also raised the

possibility of clozapine-induced AIN, subsequently

confirmed by histology. The renal function of our

patient also improved spontaneously after removing

the index medication.

In conclusion, this case highlights the rare

but important potential side-effect of clozapine.

In addition to monitoring cell counts, regular

monitoring of renal function is recommended

after initiation of clozapine. Early involvement of

nephrologists can provide early recognition of this

entity with prompt investigation and treatment.

References

1. Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury.

Lancet 2012;380:756-66. Crossref

2. Praga M, González E. Acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney

Int 2010;77:956-61. Crossref

3. Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Drug-induced acute

interstitial nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010;6:461-70. Crossref

4. Rossert J. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney

Int 2001;60:804-17. Crossref

5. Clarkson MR, Giblin L, O’Connell FP, et al. Acute interstitial

nephritis: clinical features and response to corticosteroid

therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:2778-83. Crossref

6. Kanofsky JD, Woesner ME, Harris AZ, Kelleher JP, Gittens

K, Jerschow E. A case of acute renal failure in a patient

recently treated with clozapine and a review of previously

reported cases. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord

2011;13:PCC.10br01091.

7. An NY, Lee J, Noh JS. A case of clozapine induced acute

renal failure. Psychiatry Investig 2013;10:92-4. Crossref

8. Mohan T, Chua J, Kartika J, Bastiampillai T, Dhillon R.

Clozapine-induced nephritis and monitoring implications.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2013;47:586-7. Crossref