DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144326

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Prevention in primary care is better than cure: The Hong Kong Reference Framework for

Preventive Care for Older Adults—translating evidence into practice

Cecilia KL Sin, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1;

SN Fu, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1;

Caroline SH Tsang, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Community Medicine)1;

Wendy WS Tsui, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1;

Felix HW Chan, MBBCh, FHKAM (Medicine)2

1 Primary Care Office, Department of Health, Hong Kong

2 Clinical Advisory Group on Reference Framework for Preventive Care for

Older Adults in Primary Care Settings, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Caroline SH Tsang (caroline_tsang@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

An ageing population is posing a great challenge

to Hong Kong. Maintaining health and functional

independence among older adults is of utmost

importance, and requires the collaborative efforts of

multiple health care disciplines from both the private

and public sectors. The Reference Framework for

Preventive Care for Older Adults, developed by the

Task Force on Conceptual Model and Preventive

Protocols under the auspices of the Working Group

on Primary Care, aims to enhance primary care for

this population group. The reference framework

emphasises a comprehensive, integrated, and

collaborative approach that involves providers of

primary care from multiple disciplines. In addition to

internet-based information, helpful tools in the form

of summary charts and Cue Cards are also produced

to facilitate incorporation of recommendations by

primary care providers into their daily practice. It

is anticipated that wide adoption of the reference

framework will contribute to improving older adults’

health in our community.

Introduction

Advances in medicine and increased life expectancy

mean that Hong Kong is expecting an ageing

population, and a significant increase in the number

and proportion of older adults. According to the

Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong

SAR, it is estimated that by 2041, the number of

Hong Kong residents aged 65 years and above

will increase from 0.9 million in 2011 (13% of

the population) to around 2.6 million (30% of the

projected population).1

This ageing population poses not only a threat

but also a challenge to the current health care system.

It is anticipated that the prevalence of common

chronic diseases will be further increased with a

consequent escalating demand on various health

services for older adults. Strategies to promote

health, prevent chronic diseases, and preserve

functional ability of older adults are therefore vital.

In order to provide a general reference for

provision of continuous, comprehensive, and

evidence-based care for older adults in the primary

care setting, the Reference Framework for Preventive

Care for Older Adults in Primary Care Settings2 was

developed by the Task Force on Conceptual Model

and Preventive Protocols under the auspices of the

Working Group on Primary Care. It was developed

according to the latest research evidence, with

contributions from the Clinical Advisory Group

that comprises experts from academia, professional

organisations, private and public primary care

sectors, and patient groups.

The reference framework consists of a core

document supplemented by a series of modules that

address various aspects of disease management and

preventive care for older adults.2 To date, the core

document, and the modules on health assessment

and falls have been developed.

This article summarises the main contents and

highlights a practical use of this reference framework

to enhance the delivery of preventive care for older

adults in primary care setting in Hong Kong. Details

of the evidence that supports the recommendations

are available in the core document of the reference

framework.2

Role of primary care in the preventive care of older adults

As the first point of contact, primary care providers

are in a prime position to promote health, prevent

and monitor disease, and reduce functional

disabilities.3 Primary care physicians provide health

education, risk assessment, and follow-up care

for medical conditions. They also advise and refer

patients for appropriate health care services as

necessary, and provide support and advice to family

members and carers. It is firmly established that

patient education and counselling in the primary

care setting contributes to a better understanding of

health and can thus influence an individual to adopt

health protective behaviour.4

Only 0.5% of clinical encounters among older

people at a local primary care level are initiated

for a physical checkup.5 It has been suggested that

apart from designated appointments in primary

care settings, health assessment can be performed

opportunistically over time and during multiple

visits. Indeed, every clinic visit to a primary care

provider should be seen as an opportunity to screen

for any physical, psychological, or social problems.6 7 When one considers that 80% of the Hong Kong

population have consulted a primary care provider in

1 year, with a mean of eight primary care visits per

year,8 there is ample opportunity for primary care

providers to discuss preventive care services.

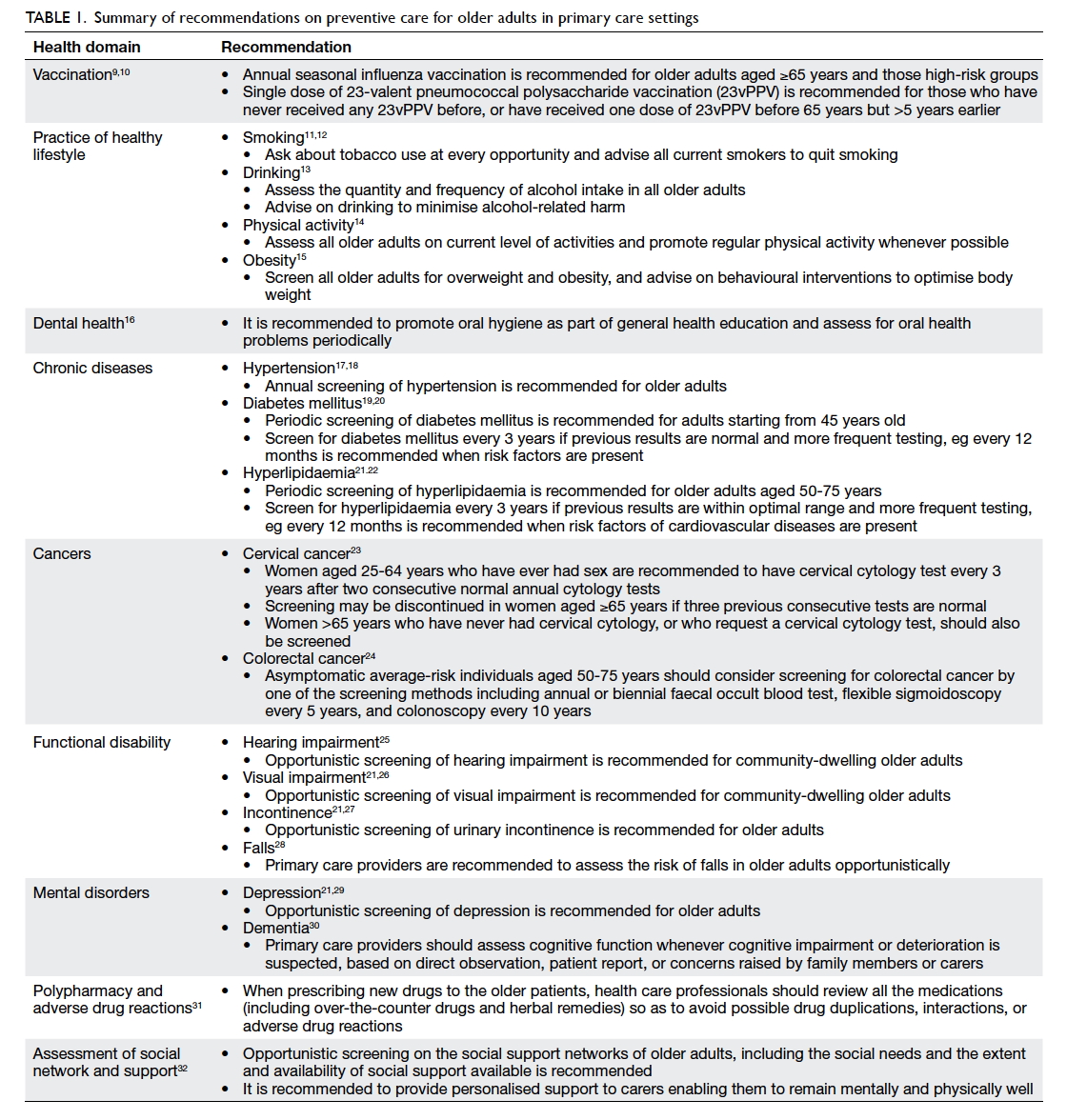

Evidence-based preventive care for older adults

The core document2 provides up-to-date evidence-based

recommendations for preventive care

of older adults in primary care setting. These

recommendations can be categorised into various

health domains, including vaccination, adoption of

a healthy lifestyle, dental health, chronic diseases,

cancers, functional disability, mental disorders,

polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions, and

assessment of social network and support. A

summary of the recommendations is listed in

Table 1.9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Although the recommendations aim to

support primary care providers in decision-making,

the care provided for each patient should also be

individualised.

Practice of evidence-based recommendations for older adults with different functional capacity

Older adults vary in their needs and functional

capacity. In a healthy active older adult, the emphasis

will often be on health promotion and disease-prevention

activities. At the other extreme, a frail

older adult with additional special needs will require

a comprehensive assessment and formulation of an

individualised care plan. The needs and condition

of an older adult may also change over time. It is

not uncommon to see a healthy active older adult

suddenly becomes disabled following an untoward

event.

In order to formulate a personalised care

plan and effectively implement the evidence-based

recommendations, three categories of functional

capacity of older adults have been proposed—independent with no known chronic diseases,

independent with chronic diseases, and older adults

with disabilities.

For all older adults and as far as applicable,

promotion of a healthy lifestyle and early

identification and appropriate management of risk

factors—such as unhealthy diet, physical inactivity,

and tobacco use—should form the cornerstone in

prevention or management of chronic diseases. A

healthy lifestyle is known to be positively associated

with better physical and mental health as well as

longevity, reduced risk of chronic diseases, and

more quality-adjusted life years.33 34 Thus promoting

a healthy lifestyle should be one of the main focuses

in healthy ageing.

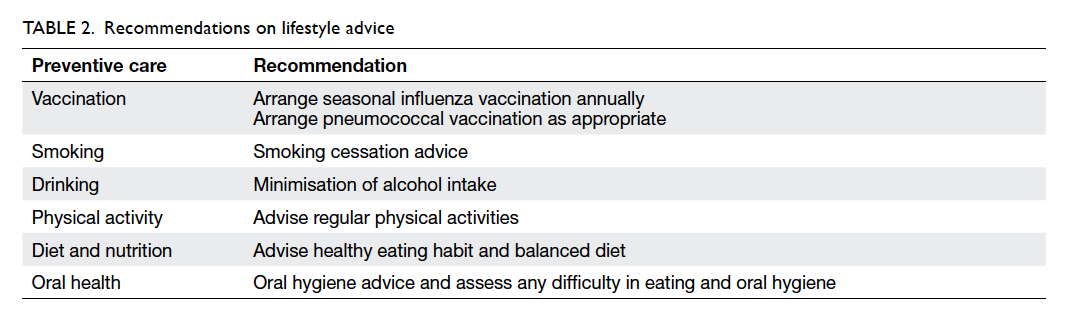

For older adults of all functional stages, a

healthy lifestyle and modification of behavioural risk

factors should be promoted as much as is practical.

Table 2 provides a summary of the recommendations.

Independent with no known chronic disease

Staying active and healthy is essential to the quality

of life. The functional decline that occurs with ageing

may be due, at least in part, to lifestyle, behaviour,

diet, and the environment, which are all modifiable

factors.35

The primary objective for this category of older

adults is to maintain optimal functional capacity

and prevent or delay the development of chronic

disease, thus helping to extend a healthy active life.

In addition to health education and promotion, a

systemic health assessment and early identification

of chronic diseases are important.

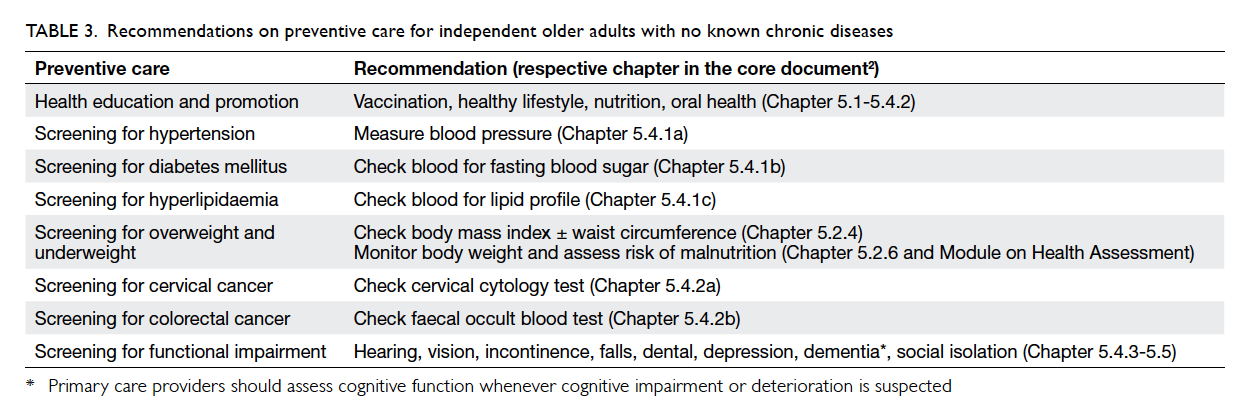

The recommended items for assessment in this

category of older adults are listed in Table 3. Details

of preventive care can be found in the respective

chapter of the core document2 and/or module

quoted in brackets.

Table 3. Recommendations on preventive care for independent older adults with no known chronic diseases

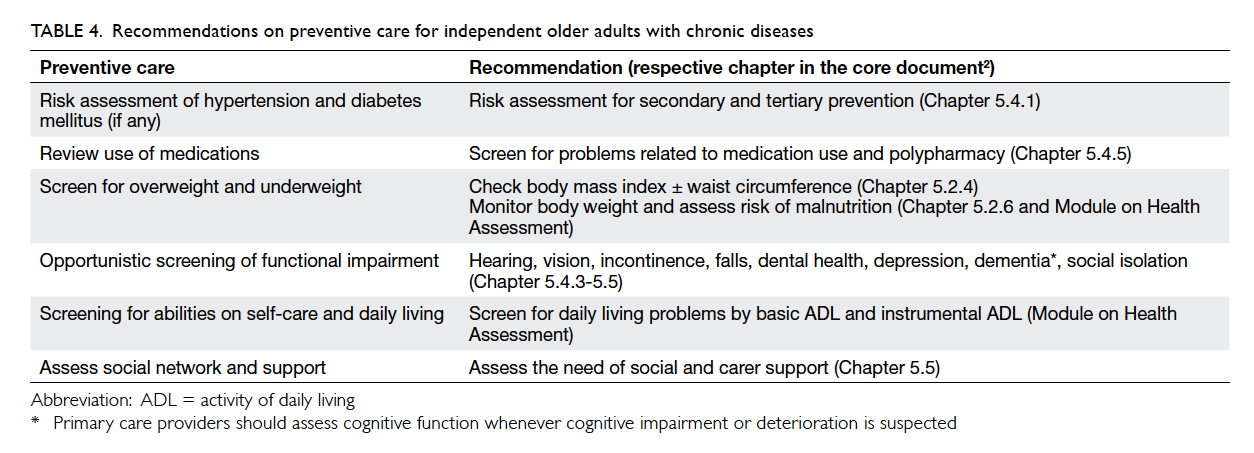

Independent with chronic diseases

Older adults with chronic diseases vary in clinical

heterogeneity, number of chronic conditions,

severity of illness, and functional limitations.

Chronic diseases exert a synergistic effect such that

the combined disabling effect of different diseases

is greater than the combined effect of each.36 As

the number of chronic diseases in an individual

increases, the risk of mortality, poor functional

status, unnecessary hospitalisations, and adverse

drug events also increases.37 38 39 Multiple chronic

diseases can be accompanied by loss of function,

reduced independence, and increased risk of

depressive illness. These subsequently contribute to

frailty and disability.37 40

The objectives of preventive services in these

older adults are to appropriately manage their

chronic diseases with reference to both secondary

and tertiary prevention, as well as to maintain

functional independence. The recommendations on

preventive care for independent older adults with

chronic diseases are summarised in Table 4. Details

about preventive care can be found in the relevant

chapter of the core document and/or module quoted

in brackets.2

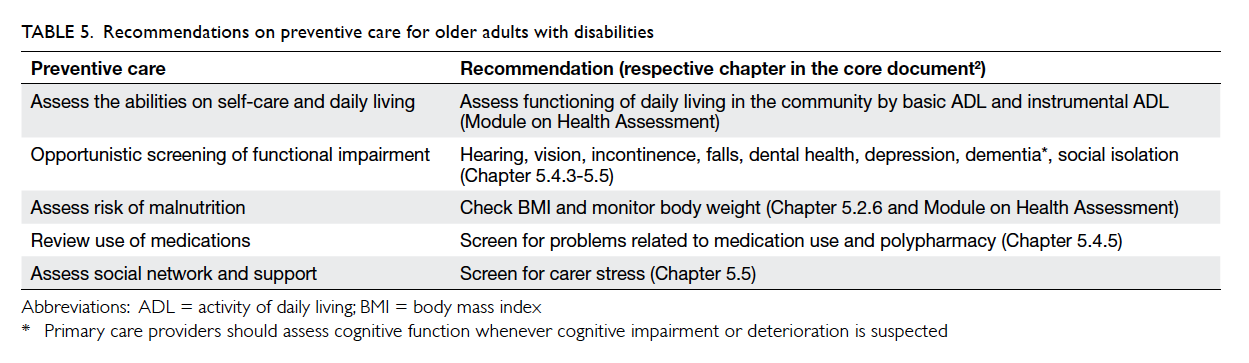

Older adults with disabilities

Older adults who suffer multiple debilitating diseases

(such as stroke, dementia, or arthritis) are likely to

face disabling barriers that inhibit or prevent their

integration into the community. Chronic pain is also

common in this group of older adults and invariably

jeopardises physical, psychological, and social

wellbeing.

The approach to this group is early intervention

to prevent further loss of function, so as to maintain

optimal functional capacity and improve quality

of life, and also facilitate integration into society

for those who have relatively mild disability. A

comprehensive assessment should be offered to

this group of older adults with complex needs, and

should encompass physical, psychological, and social

aspects of care (eg ability in self-care, hearing and

visual impairment, incontinence, falls, depression,

cognitive impairment, malnutrition, polypharmacy,

social support, and carer stress).

The recommendations on preventive care for

older adults with disabilities are listed in Table 5.

Details about preventive care can again be found in

the relevant chapter of the core document and/or

module quoted in brackets.2

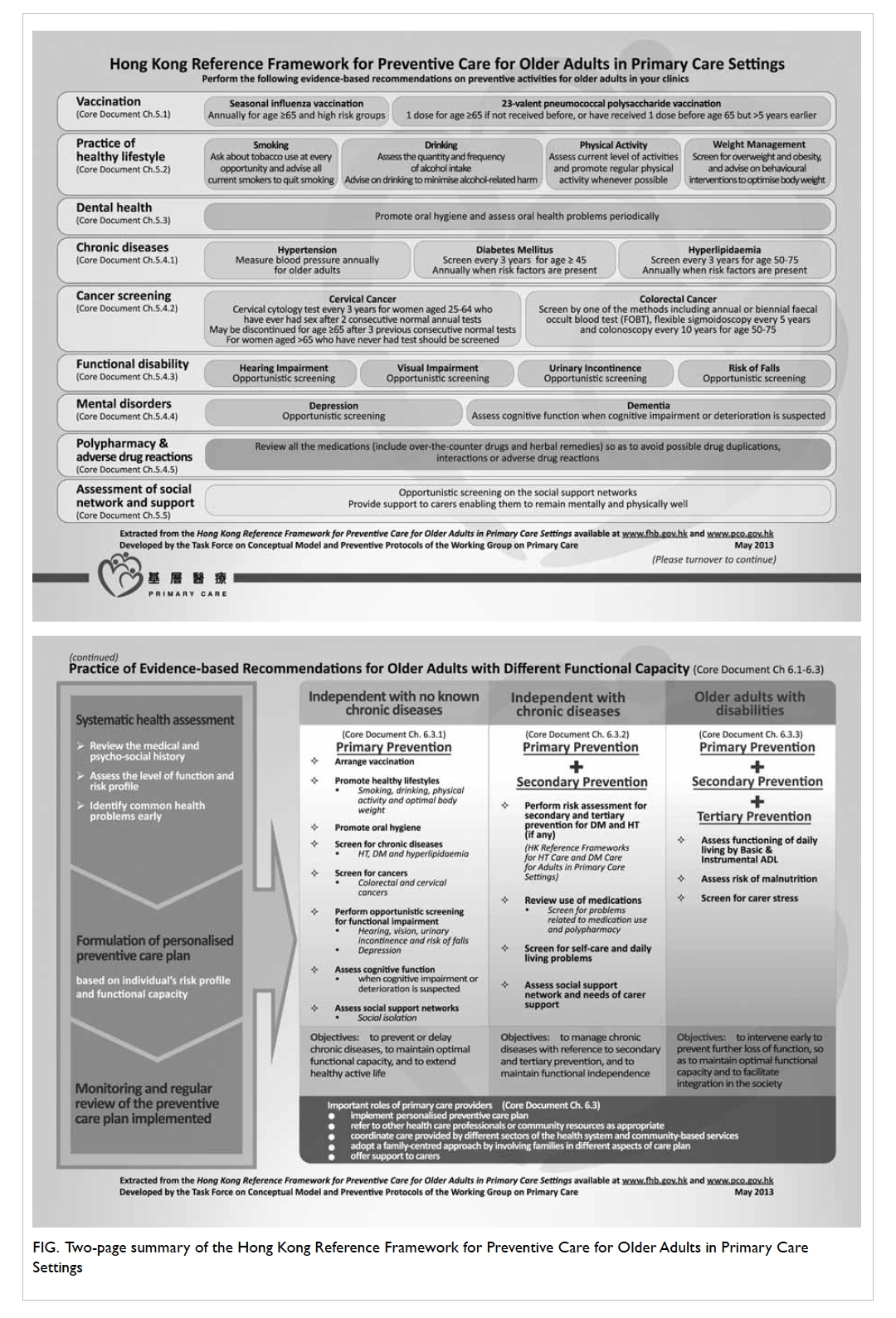

The two-page summary

A 2-page summary (Fig) has been developed to

provide a quick reference for primary care providers

on preventive care for older adults. It provides a

summary of the evidence-based recommendations

for preventive activities and the practice of

recommendations for older adults with different

functional capacities. The relevant chapter of the

preventive care is stated in the summary for further

information and supporting evidence. It can also be

downloaded from the Primary Care Office website

(http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/Summary_page_older_adult.pdf).

Figure. Two-page summary of the Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for Older Adults in Primary Care Settings

Patient education materials

In a busy clinic, patient education material is an

effective means to deliver preventive care information

to patients and their carers. The resources related to

the health care of older adults are available in Annex

3 of the core document.2 These resources provide

information for the local community and help

primary care providers coordinate care with other

professionals and specialists. Families can also be

put in touch with community-based services. With

appropriate care, older adults can achieve optimum

health and improve their quality of life.

Conclusion

Effective preventive care of older adults can be

achieved through health education and promotion,

prevention and monitoring of diseases, and reduction

of functional disabilities. Primary care providers

play an important role in providing patient-centred,

comprehensive, continuing, and coordinated

preventive care to older adults in the community. In

addition, continued efforts of different health care

providers, professional organisations, social service

agencies, and all stakeholders are needed to provide

a supportive environment for active and healthy

ageing. It is hoped that through the development

and promotion of this reference framework, more

emphasis can be placed on preventive care in older

adults. This will improve their health and promote

healthy ageing.

References

1. Hong Kong Population Projections 2012-2041.

Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR. 2012 July. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B1120015052012XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed Jun 2015.

2. Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for

Older Adults in Primary Care Settings 2012. Available

from: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/ref_framework_adults.pdf. Accessed 11 Nov 2014.

3. Brotons C, Bulc M, Sammut MR, et al. Attitudes toward

preventive services and lifestyle: the views of primary care

patients in Europe. The EUROPREVIEW patient study.

Fam Pract 2012;29 Suppl 1:i168-76. Crossref

4. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss

BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with

limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:874-7. Crossref

5. Lo YY, Lam CL, Mercer SW, et al. Patient morbidity and

management patterns of community-based primary health

care services in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17(3 Suppl 3):33-7.

6. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination.

The Periodic Health Examination 1984. A Report of

the Periodic Health Examination Task Force. Ottawa,

Ontario: Health Services Directorate, Health Services and

Promotion Branch, Department of National Health and

Welfare; 1984: 15.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical

preventive services. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams &

Wilkins; 1996.

8. Lam CL, Leung GM, Mercer SW, et al. Utilisation patterns

of primary health care services in Hong Kong: does having

a family doctor make any difference? Hong Kong Med J

2011;17(3 Suppl 3):28-32.

9. Nichol KL, Nordin JD, Nelson DB, Mullooly JP, Hak E.

Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in the community-dwelling

elderly. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1373-81. Crossref

10. Moberley SA, Holden J, Tatham DP, Andrews RM.

Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(1):CD000422. Crossref

11. Ranney L, Melvin C, Lux L, McClain E, Lohr KN. Systematic

review: smoking cessation intervention strategies for

adults and adults in special populations. Ann Intern Med

2006;145:845-56. Crossref

12. Lam TH, Li ZB, Ho SY, et al. Smoking, quitting and

mortality in an elderly cohort of 56,000 Hong Kong

Chinese. Tob Control 2007;16:182-9. Crossref

13. Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J;

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling

interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful

alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med

2004;140:557-68. Crossref

14. Elward K, Larson EB. Benefits of exercise for older adults. A

review of existing evidence and current recommendations

for the general population. Clin Geriatr Med 1992;8:35-50.

15. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and

treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the Evidence

Report. NIH Publication No. 98-4083. National Institutes

of Health–National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute–Obesity Education Initiative; 1998.

16. Kressin NR, Boehmer U, Nunn ME, Spiro A 3rd. Increased

preventive practices lead to greater tooth retention. J Dent

Res 2003;82:223-7. Crossref

17. Hong Kong Reference Framework for Hypertension Care

for Adults in Primary Care Settings. Available from: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/RF_HT_full.pdf. Accessed Jun 2015.

18. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’

Collaboration: Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T, et al. Effects

of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major

cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis

of randomised trials. BMJ 2008;336:1121-3. Crossref

19. Hong Kong Reference Framework for Diabetes Care for

Adults in Primary Care Settings. Available from: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/RF_DM_full.pdf. Accessed Jun 2015.

20. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for type

2 diabetes mellitus in adults: U.S. Preventive Services

Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med

2008;148:846-54. Crossref

21. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice 8th edition. Available from: http://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/redbook/. Accessed 17 Apr 2014.

22. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lipid

disorders in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

recommendation statement. June 2008. Available from:

http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf08/lipid/lipidrs.htm. Accessed 17 Apr 2014.

23. Sasieni PD, Cuzick J, Lynch-Farmery E. Estimating

the efficacy of screening by auditing smear histories of

women with and without cervical cancer. The National

Co-ordinating Network for Cervical Screening Working

Group. Br J Cancer 1996;73:1001-5. Crossref

24. The Cancer Expert Working Group (CEWG) on Cancer

Prevention and Screening. Recommendations on colorectal cancer screening. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/recommendations_on_crc_screening_2010.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 2014.

25. Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Fleming C, Beil T. Screening

adults aged 50 years or older for hearing loss: a review of

the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Ann Intern Med 2011;154:347-55. Crossref

26. Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C. Screening older adults

for impaired visual acuity: a review of the evidence for

the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med

2009;151:44-58, W11-20.

27. O’Neil B, Gilmour D, Approach to urinary incontinence in

women. Diagnosis and management by family physicians.

Can Fam Physician 2003;49:611-8.

28. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al.

Interventions for preventing falls in older people

living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2009:(2):CD007146. Crossref

29. O’Connor EA, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Gaynes BN. Screening

for depression in adult patients in primary care settings: a

systematic evidence review. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:793-803. Crossref

30. Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr

KN; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for

dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for

the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med

2003;138:927-37. Crossref

31. Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, Berthenthal

D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality

in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1516-23. Crossref

32. Lou VW. Caregiving burden: congruence of health

assessment between caregivers and care receivers. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr

2010;5:21-4.

33. Myint PK, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Bingham SA, Khaw KT.

Combined effect of health behaviours and risk of first ever

stroke in 20,040 men and women over 11 years’ follow-up

in Norfolk cohort of European Prospective Investigation of

Cancer (EPIC Norfolk): prospective population study. BMJ

2009;338:b349. Crossref

34. Myint PK, Smith RD, Luben RN, et al. Lifestyle behaviours

and quality-adjusted life years in middle and older age. Age

Ageing 2011;40:589-95. Crossref

35. Victor CH, Howse K. Effective health promotion with

vulnerable groups: older people. London: Health Education

Authority; 1999.

36. Scott KM, Von Korff M, Alonso J, et al. Mental-physical

co-morbidity and its relationship with disability: results

from the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med

2009;39:33-43. Crossref

37. Lee TA, Shields AE, Vogeli C, et al. Mortality rate in

veterans with multiple chronic conditions. J Gen Intern

Med 2007;22 Suppl 3:403-7. Crossref

38. Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic

conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and

implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen

Intern Med 2007;22 Suppl 3:391-5. Crossref

39. Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures,

and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the

elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2269-76. Crossref

40. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Katon W, Lin EH. Disability

and depression among high utilizers of health care. A

longitudinal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:91-100. Crossref