Hong Kong Med J 2015 Aug;21(4):310–7 | Epub 17 Jul 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144393

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Indications for and pregnancy outcomes of cervical cerclage: 11-year comparison of patients undergoing history-indicated, ultrasound-indicated, or rescue cerclage

Lucia LK Chan, MB, BS, MRCOG1;

TW Leung, PhD, FRCOG1;

TK Lo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2;

WL Lau, MB, BS, FRCOG1;

WC Leung, MD, FRCOG1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Lucia LK Chan (lucia118@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To review and compare pregnancy

outcomes of patients undergoing history-indicated,

ultrasound-indicated, or rescue cerclage.

Design: Case series with internal comparison.

Setting: A regional obstetric unit in Hong Kong.

Patients: Women undergoing cervical cerclage at

Kwong Wah Hospital between 1 January 2001 and

31 December 2011.

Interventions: Cervical cerclage.

Main outcome measures: Pregnancy outcomes

including miscarriage, gestational age at delivery,

birth weight, and duration of pregnancy prolongation.

Results: Overall, 47 patients were included. Nine

(19.1%) pregnancies resulted in miscarriage. The

median gestational age at delivery was 35.7 weeks.

Among the 23 patients who had history-indicated

cerclage, only four (17.4%) had three or more previous second-trimester miscarriages or

preterm deliveries. Among the 15 patients who had

ultrasound-indicated cerclage, preoperative cervical

length of ≤1.5 cm was associated with shorter

prolongation of pregnancy, compared with that

of >1.5 cm (median, 12.1 vs 18.4 weeks; P=0.009).

Among the nine women who had rescue cerclage,

those who underwent the procedure before 20 weeks

of gestation delivered earlier than those underwent

cerclage later (median, 22.5 vs 34.1 weeks; P=0.048).

Conclusions: Patients eligible for the Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists–recommended

history-indicated cerclage remain few. The majority

of patients may benefit from serial ultrasound

monitoring of cervical length with or without

ultrasound-indicated cerclage.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Women who had rescue cerclage before 20 weeks of gestation delivered significantly earlier than those who had the procedure performed later, supporting the expert opinion in the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guideline.

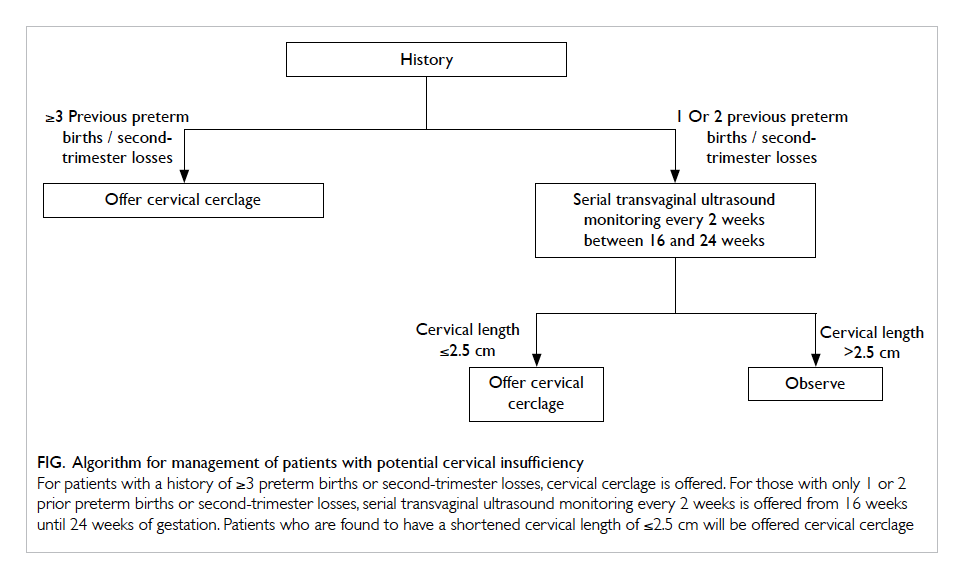

- The majority of patients may benefit from serial ultrasound monitoring of cervical length with or without ultrasound-indicated cerclage. A proposed algorithm on the management of patients, taking into consideration the RCOG guideline, is presented.

Introduction

Cervical cerclage was introduced by Shirodkar1

and McDonald2 in the 1950s, and has since become

a common obstetric practice for the secondary

prevention of preterm birth.3 4 Cervical cerclage is

performed in patients with a history of cervical

insufficiency; preterm labour or second-trimester

miscarriage; cervical dilatation in the second

trimester; or shortened cervix noted on transvaginal

ultrasound examination.

Although cervical cerclage is a common

obstetric procedure, there is still controversy

regarding its efficacy and patient selection. While

some studies showed that cervical cerclage

did not prolong gestation or improve neonatal

survival,5 6 7 8 9 others suggested that the procedure was

beneficial.10 11 12 13 14 15 For instance, a large trial demonstrated

that the incidence of preterm delivery before 33

weeks was halved by cervical cerclage among women

with a history of three or more preterm

deliveries before 37 weeks.10 It was shown in a meta-analysis11

and another study12 that among women

with shortened cervical length with or without

prior preterm birth, the risk of preterm birth with

or without perinatal mortality was significantly

reduced by cerclage. Rescue cerclage was also found

to prolong pregnancy, reduce the risk of preterm

labour,13 14 and improve neonatal survival and birth

weight, even in women considered at low risk of

preterm delivery in view of their obstetric

history.15

Decisions for cervical cerclage are difficult

and are often based on the clinical judgement of the

senior obstetrician. The guideline on cervical cerclage

published by the Royal College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (RCOG) in 2011, which classifies

cervical cerclage into history-indicated, ultrasound-indicated and rescue cerclage, provides updated

evidence in this area.16

Nevertheless, on review of the literature

worldwide, no studies have been reported to

investigate systematically the use and outcomes

of cervical cerclage according to this new RCOG

classification. Hence, this study aimed to review

the indications and the pregnancy outcomes

(miscarriage, gestational age at delivery, birth weight,

prolongation of pregnancy, and rate of preterm birth

before 34 weeks) of cervical cerclage in a regional

obstetric unit in Hong Kong according to the RCOG

categorisation. Any change in practice of cervical

cerclage in the unit over 11 years was also reviewed.

Methods

This was a retrospective review of patients who had

cervical cerclage performed in a regional obstetric

unit in Hong Kong between 1 January 2001 and

31 December 2011. Ethics approval from the local

institutional review board (Kowloon West Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee Reference: KW/EX-13-041[61-62]) was obtained. Patients who had

undergone cervical cerclage were identified by the

Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System, which

is a computerised database of the Hospital Authority,

Hong Kong, using the key word “cervical cerclage”.

The clinical data for these patients were retrieved

and reviewed.

The patients were divided into three

subgroups for data analysis. Group 1 included

patients with history-indicated cerclage, that is,

cerclage was performed in women with obstetric or

gynaecological risk factors for spontaneous second-trimester

loss or preterm delivery. Group 2 were

patients with ultrasound-indicated cerclage, that

is, cerclage was performed for women with cervical

shortening (<2.5 cm) detected by transvaginal

ultrasound examination, without exposure of fetal

membranes in the vagina. This group comprised

women who planned for history-indicated cerclage

with preoperative sonographic finding of shortened

cervix; had a history of preterm delivery before

37 weeks or second-trimester miscarriage(s) and

underwent ultrasound monitoring of cervical length;

or were incidentally found to have sonographic

cervical shortening. Regular ultrasound examination

was not performed for all patients and, if done, the

frequency of monitoring was determined individually.

Group 3 consisted of patients undergoing rescue

cerclage, that is, cerclage was performed for women

with premature cervical dilatation and exposure of

fetal membranes in the vagina, which was either

detected by ultrasound examination of the cervix

or by speculum/physical examination for symptoms

such as vaginal discharge, bleeding, or ‘sensation of

pressure’, with or without a history of preterm

birth before 37 weeks or second-trimester losses.

The definitions of history-indicated cerclage

and ultrasound-indicated cerclage in this study were

not exactly the same as the RCOG definitions,16

which suggest that history-indicated cerclage should

be offered to women with three or more previous preterm births and/or second-trimester

losses, while ultrasound-indicated cerclage should

be offered to women with one or more previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss and

sonographic cervical shortening (≤2.5 cm) before

24 weeks of gestation. To explore the significance

of the differences in the category definitions, a sub-analysis

was performed by dividing the present

cohort into two groups. Group A included women

who underwent history-indicated or ultrasound-indicated

cerclage as defined by the RCOG guideline. Group B included women who had the procedure

performed without strictly following the RCOG

guideline.

All cervical cerclage procedures were

performed by a senior obstetrician using the

McDonald’s technique with Mersilene tape

(Ethicon, West Somerville [NJ], US). Perioperative

management—such as the use of prophylactic

antibiotics and/or tocolytics, bed rest, and the

choice of anaesthesia—was at the discretion of the

operating team. The interval between the diagnosis

of cervical incompetence and the performance of

rescue cervical cerclage ranged from 0 to 3 days.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US) was used for statistical analysis. The pregnancy

outcomes studied included miscarriage, gestational

age at delivery, birth weight, and duration of

prolongation of pregnancy. Kruskal-Wallis test and

Pearson Chi squared test were employed to analyse

the relationship between indication for cerclage

and various pregnancy outcomes. Patients who had

history-indicated or ultrasound-indicated cerclage

as defined by the RCOG guideline (group A) were

compared with patients who had the procedure

performed without strictly following the RCOG

definition (group B) by the Mann-Whitney U

test and Fisher’s exact test. Fisher’s exact test and

Mann-Whitney U test were used, respectively, to

compare the indications for cerclage and the various

pregnancy outcomes between two different time

periods (2001-2005 vs 2006-2011). A P value of less

than 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 47 patients with a singleton pregnancy were

included in this study. The majority (87.2%) were

Chinese. No immediate operative complications

associated with cervical cerclage (namely membrane

rupture or miscarriage within 1 week) occurred

except for one miscarriage.

Among the 47 patients, nine (19.1%)

pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, and 28 (59.6%)

patients delivered after 34 weeks of gestation. The

median gestational age at delivery was 35.7 (range,

14.9-40.1) weeks, with a median birth weight of

2270 (range, 75-3960) g. The median prolongation

of pregnancy after cervical cerclage was 17.3

(range, 0.3-27.1) weeks. Among the 38 patients who

delivered after 24 weeks of gestation, 29 (76.3%)

delivered by normal spontaneous delivery, eight

(21.1%) by lower segment caesarean section, and one

(2.6%) by vacuum extraction.

Patients undergoing history-indicated cerclage (group 1; n=23)

Cerclage was performed at a median gestation

of 14.6 (range, 12.4-19.6) weeks (Table 1). The median cervical length of the 20 patients who had it

measured preoperatively by ultrasound examination

was 3.5 (range, 2.5-4.8) cm. Four (17.4%) patients

had three or more previous second-trimester

miscarriages or preterm deliveries (ie the

true history-indicated cerclage group as defined

by the RCOG guidelines) and 13 (56.5%) had two

or more second-trimester miscarriages

or preterm deliveries. One patient did not have

previous second-trimester miscarriage or preterm

delivery, but had a history of large loop excision

of transformation zone for cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia, two terminations of pregnancy, and

recurrent first-trimester miscarriages.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of patients with different indications for cervical cerclage

No significant association was found between

pregnancy outcomes and the gestation at which

cerclage was performed. The pregnancy outcomes

of the four women with three or more previous second-trimester miscarriages or preterm

deliveries were compared with the other 19

women who had less than three second-trimester

miscarriages or preterm deliveries. The former

group tended to have a better pregnancy outcome,

with higher gestational age at delivery (median,

38.1 weeks vs 37.4 weeks) and heavier birth weight

(median, 3135 vs 2570 g) than the latter group,

although these differences did not reach statistical

significance.

Patients undergoing ultrasound-indicated cerclage (group 2; n=15)

Cerclage was performed at a median gestation of

18.6 (range, 14.3-23.4) weeks (Table 1). Shortened

cervical length with or without funnelling of the

cervix was detected on ultrasound examination. The

median cervical length was 1.5 (range, 0-2.4) cm. All

patients had cervical length of <2.5 cm.

Patients with a preoperative cervical length

of ≤1.5 cm had significantly shorter prolongation

of pregnancy compared with patients with a

preoperative cervical length of >1.5 cm (median,

12.1 vs 18.4 weeks, P=0.009). Seven (46.7%) patients

had cervical funnelling. No significant difference

in pregnancy outcomes was detected between

patients with and without cervical funnelling seen

in the preoperative ultrasound examination. Among

the 15 patients undergoing ultrasound-indicated

cerclage, 13 (86.7%) had a history of

second-trimester miscarriages or preterm deliveries.

No significant difference in pregnancy outcomes

was found between patients with or without a history of second-trimester miscarriages or preterm

deliveries.

Patients undergoing rescue cerclage (group 3; n=9)

Rescue cerclage was performed at a median

gestation of 19.3 (range, 16.1-23.0) weeks (Table 1).

Cervical dilatation ranged from 2 to 3 cm at the time

of diagnosis. Among the nine patients undergoing

rescue cerclage, six (66.7%) had a history of

second-trimester miscarriages or preterm deliveries.

The diagnosis of cervical dilatation among these six

women was made by either ultrasound assessment

or physical examination based on symptoms. One

patient had history-indicated cervical cerclage

performed at a private hospital at 12 weeks of

gestation. She presented with increased vaginal

discharge at 22 weeks and was found to have cervical

dilatation with a loosened cerclage stitch. Rescue

cerclage was performed.

All the patients who miscarried after rescue

cerclage had the procedure performed before 20

weeks of gestation. Women who underwent cerclage

before 20 weeks delivered at an earlier gestation

(median, 22.5 vs 34.1 weeks; P=0.048) and had smaller

babies (median birth weight, 565 vs 2190 g; P=0.048)

than women who had cerclage at a later gestation.

Comparison among the three groups of patients

There were no significant differences in age, body

mass index, or parity between the three groups.

Cerclage was performed at a significantly earlier

gestation for patients with history-indicated cerclage

compared with the other two groups (P<0.001; Table 1).

Regarding the pregnancy outcomes, it seems

that patients undergoing rescue cerclage had a higher

incidence of miscarriage than the other two groups

(44.4% vs 20.0% in the ultrasound-indicated group

and 8.7% in the history-indicated group), although

the differences did not reach statistical significance

(P=0.07), probably because of the small number of

patients included in each group (Table 1).

Patients in the history-indicated and

ultrasound-indicated cerclage groups had

significantly longer prolongation of pregnancy,

delivered at later gestation, and had heavier birth

weight babies than women in the rescue cerclage

group (Table 1). Nevertheless, there were no

statistically significant differences in the gestational

age at delivery or birth weight between patients in

history-indicated cerclage group and the ultrasound-indicated

group, although the former group had significantly longer

prolongation of pregnancy than the latter group (P=0.002).

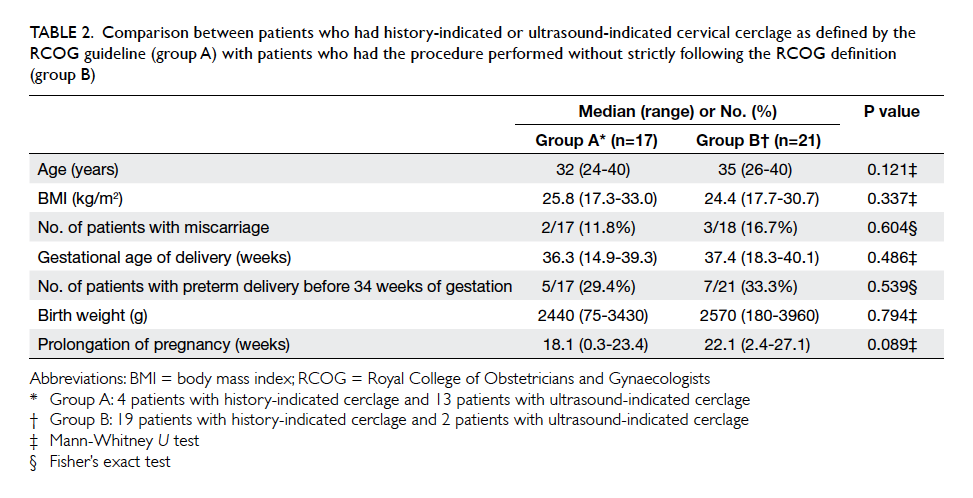

Comparison between patients in group A and group B according to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists definition

Comparison between patients who had history-indicated

or ultrasound-indicated cerclage as

defined by the RCOG guideline (group A) with

patients who had the procedure performed without

strictly following the RCOG definition (group B) was

made. Group A consisted of four patients who had

history-indicated cerclage and 13 patients who had

ultrasound-indicated cerclage. Group B comprised

19 patients who had history-indicated cerclage

and two patients who had ultrasound-indicated

cerclage. No significant differences were detected

in the demographic characteristics between the

two groups. There were also no significant differences in

the pregnancy outcomes between the two groups,

including miscarriage rate, gestational age at delivery,

preterm delivery rate before 34 weeks of gestation,

birth weight, and prolongation of pregnancy (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison between patients who had history-indicated or ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage as defined by the RCOG guideline (group A) with patients who had the procedure performed without strictly following the RCOG definition (group B)

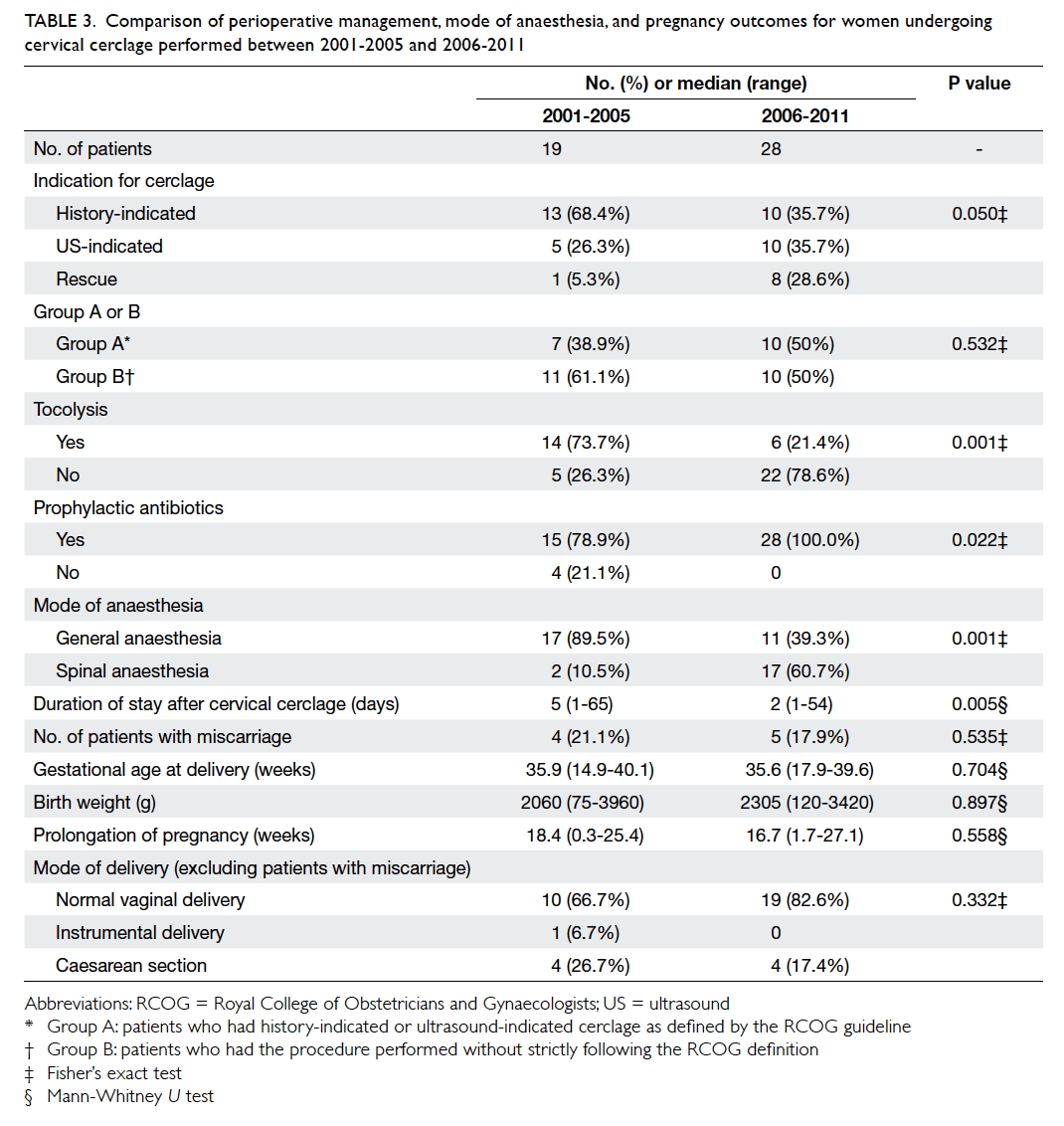

Comparison of the cerclage practice between 2001-2005 and 2006-2011

There was a trend for more ultrasound-indicated

cerclage and rescue cerclage in 2006-2011 than in

2001-2005. More history-indicated or ultrasound-indicated

cerclages were performed according to

the RCOG’s recommendation in 2006-2011 than in

2001-2005 (50% vs 38.9%), although the difference

did not reach statistical significance (P=0.532),

probably because of the small sample size (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of perioperative management, mode of anaesthesia, and pregnancy outcomes for women undergoing cervical cerclage performed between 2001-2005 and 2006-2011

Pregnancy outcomes were similar between

the two periods. However, there was less use of

prophylactic tocolysis, but more frequent use of

spinal anaesthesia and prophylactic antibiotics in

2006-2011 than in 2001-2005. The median duration of

hospital stay was also significantly shorter in 2006-2011 than in 2001-2005 (Table 3).

Discussion

This retrospective study reviewed systematically the

use and outcomes of cervical cerclage according to

the new 2011 RCOG categorisation,16 although not

all cases followed strictly the exact definition of

history-indicated or ultrasound-indicated cerclage

in the RCOG guideline. The data from the study may

help provide more evidence on the application of the

new guideline for making the decision for cervical

cerclage among women at risk of or diagnosed with

cervical incompetence.

In this study, only four (17.4%) patients

fulfilled the RCOG recommendation16 for history-indicated

cerclage (ie ≥3 previous second-trimester

miscarriages or preterm deliveries), although more

than half of the women in the group (n=13, 56.5%)

had a history of two or more second-trimester

miscarriages or preterm deliveries. This

suggests that in clinical practice, women eligible

for cerclage based on their obstetric history alone

are few and, hence, serial ultrasound monitoring of

cervical length is needed for most of the women at

risk for cervical incompetence.

The optimal cervical length for recommending

cerclage is controversial.12 17 One multicentre trial

suggested that cerclage should be performed at

cervical length of <1.5 cm,12 whereas a meta-analysis

suggested that cerclage should be done for women

with a singleton gestation with a previous preterm

birth and cervical length of <2.5 cm.17 Our study

showed that patients with preoperative cervical

length of ≤1.5 cm had shorter prolongation of

pregnancy compared with those with preoperative

cervical length of 1.5 to 2.4 cm, supporting the

recommendation that cervical cerclage should be

offered if sonographic cervical shortening to ≤2.5

cm is detected (Fig). No significant difference in

pregnancy outcomes was detected between patients

with and without preoperative sonographic cervical

funnelling. Review of the literature also suggests that

cervical funnelling is not an independent risk factor

for preterm birth.18 Hence, cervical funnelling is not

recommended as a criterion to offer cerclage.

Figure. Algorithm for management of patients with potential cervical insufficiency

For patients with a history of ≥3 preterm births or second-trimester losses, cervical cerclage is offered. For those with only 1 or 2 prior preterm births or second-trimester losses, serial transvaginal ultrasound monitoring every 2 weeks is offered from 16 weeks until 24 weeks of gestation. Patients who are found to have a shortened cervical length of ≤2.5 cm will be offered cervical cerclage

Group A comprised patients who had three

or more previous preterm deliveries

or second-trimester miscarriages in the history-indicated

cerclage group and patients with one or

more previous preterm delivery or second-trimester

miscarriage in the ultrasound-indicated

cerclage group, and therefore was expected to carry

a higher risk for preterm delivery or miscarriage

and, hence, a worse pregnancy outcome compared

with group B patients, who did not strictly fulfil the

RCOG recommendation. Interestingly, no significant

difference in pregnancy outcomes was detected

between group A and group B patients. This may

be due to the small sample size in each group. This,

however, may mean that a less stringent criterion

to offer cerclage other than the present RCOG

recommendation may still be helpful for women at

risk for cervical incompetence. A prospective study

with a larger sample size to compare the pregnancy

outcomes between these two groups of patients is

warranted.

Women who had rescue cerclage before 20

weeks delivered significantly earlier than those

who underwent the procedure later than 20 weeks.

Although it is stated in the 2011 RCOG guideline that

“in cases presenting before 20 weeks of gestation,

insertion of a rescue cerclage is highly likely to result

in a preterm delivery before 28 weeks of gestation”,16

this is based on expert opinion only, rather than

data from previous studies. The result from this

study provides new evidence to support such expert

opinion.

Among patients with history-indicated or

ultrasound-indicated cerclage, more patients fulfilled

the RCOG’s recommendation in 2006-2011 than

in 2001-2005 (50.0% vs 38.9%). This suggests that

even before the publication of the RCOG guideline

in 2011, the practice of cervical cerclage has already

been changing, with a shift towards more stringent

criteria for offering cerclage.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study reviewed systematically the use and

outcomes of cervical cerclage according to the

categories in the new 2011 RCOG guideline.16 The

data obtained may help in patient selection and

counselling for cerclage. The major limitations

include small sample size and lack of control groups.

Moreover, not all patients included in the history-indicated

and ultrasound-indicated groups fulfilled

exactly the strict RCOG definitions for the respective

groups.

The way forward

Although the RCOG guideline recommends history-indicated

cerclage be performed in patients with a

history of three or more previous second-trimester

miscarriages or preterm deliveries, in

clinical practice, this group of patients remains

small. In the present study, only 17.4% of patients

in the history-indicated cerclage group fulfilled

such criteria. The majority of patients with potential

cervical insufficiency encountered are those with a

history of one or two previous second-trimester

miscarriages or preterm deliveries, who may benefit

from serial ultrasound monitoring of cervical length

with or without ultrasound-indicated cerclage. Based

on the findings from this study, an algorithm for

the management of patients with potential cervical

insufficiency is proposed (Fig).

A major limitation of ultrasound monitoring

is the difficulty of timely identification of

sudden cervical shortening and dilatation. The

recommended frequency of ultrasound surveillance

is not well established. Since this study demonstrated

that rescue cerclage performed before 20 weeks

of gestation was associated with a much poorer

pregnancy outcome than procedures done at a later

gestation, it is recommended that among patients

with a history of one or two previous preterm births

or second-trimester miscarriages, serial ultrasound

monitoring should be performed every 2 weeks

between 16 and 24 weeks of gestation (Fig). This may help optimise the early detection of cervical

shortening in time and, hence, allow ultrasound-indicated

cerclage be performed instead of rescue

cerclage. Nevertheless, such practice requires a

greater demand on manpower to perform ultrasound

examinations and may not be applicable in small

units with few staff. In order to improve the quality

of care for patients with potential cervical

insufficiency, allocation of resources for serial

ultrasound monitoring for this group of patients is

warranted.

Conclusions

Patients eligible for history-indicated cerclage

according to the RCOG recommendation remain

few. The majority of patients may benefit from serial

ultrasound monitoring of cervical length with or

without ultrasound-indicated cerclage, which is

preferably performed at a cervical length between

1.5 and 2.5 cm.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Shirodkar VN. A new method of operative treatment for

habitual abortion in the second trimester of pregnancy.

Antiseptic 1955;52:299-300.

2. McDonald IA. Suture of the cervix for inevitable

miscarriage. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1957;64:346-50. Crossref

3. Spong CY. Prediction and prevention of recurrent

spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:405-15. Crossref

4. Flood K, Malone FD. Prevention of preterm birth. Semin

Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;17:58-63. CrossRef

5. Rush RW, Isaacs S, McPherson K, Jones L, Chalmers I,

Grant A. A randomized controlled trial of cervical cerclage

in women at high risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Br

J Obstet Gynaecol 1984;91:724-30. Crossref

6. Berghella V, Daly SF, Tolosa JE, et al. Prediction of preterm

delivery with transvaginal ultrasonography of the cervix in

patients with high-risk pregnancies: does cerclage prevent

prematurity? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:809-15. Crossref

7. Rust OA, Atlas RO, Reed J, van Gaalen J, Balducci J.

Revisiting the short cervix detected by transvaginal

ultrasound in the second trimester: why cerclage therapy

may not help. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:1098-105. Crossref

8. Berghella V, Odibo AO, Tolosa JE. Cerclage for prevention

of preterm birth in women with a short cervix found on

transvaginal ultrasound examination: a randomized trial.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:1311-7. Crossref

9. To MS, Alfirevic Z, Heath VC, et al. Cervical cerclage for

prevention of preterm delivery in women with short cervix: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1849-53. Crossref

10. Final report of the Medical Research Council/Royal

College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists multicentre

randomised trial of cervical cerclage. MRC/RCOG

Working Party on Cervical Cerclage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1993;100:516-23. Crossref

11. Berghella V, Odibo AO, To MS, Rust OA, Althuisius SM.

Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography: meta-analysis

of trials using individual patient-level data. Obstet

Gynecol 2005;106:181-9. Crossref

12. Owen J, Hankins G, Iams JD, et al. Multicenter randomized

trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk

women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:375.e1-8. Crossref

13. Olatunbosun OA, al-Nuaim L. Turnell RW. Emergency

cerclage compared with bed rest for advanced cervical

dilatation in pregnancy. Int Surg 1995;80:170-4.

14. Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, van Geijn HP;

Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage

trial. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized

cerclage trial: emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed

rest alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:907-10. Crossref

15. Daskalakis G, Papantoniou N, Mesogitis S, Antsaklis A.

Management of cervical insufficiency and bulging fetal

membranes. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:221-6. Crossref

16. Cervical cerclage (Green-top Guideline No. 60), May 2011. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2011.

17. Berghella V, Keeler SM, To MS, Althuisius SM, Rust OA.

Effectiveness of cerclage according to severity of cervical

length shortening: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 2010;35:468-73. Crossref

18. To MS, Skentou C, Liao AW, Cacho A, Nicolaides KH.

Cervical length and funneling at 23 weeks of gestation

in the prediction of spontaneous early preterm delivery.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001;18:200-3. Crossref