Hong Kong Med J 2015 Jun;21(3):208–16 | Epub 9 Apr 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144304

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effectiveness of a discharge planning and community support programme in preventing readmission of high-risk older patients

Francis OY Lin, MB, BS, MRCP (UK);

James KH Luk, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine);

TC Chan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine);

Winnie WY Mok, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine);

Felix HW Chan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)

Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital, 9 Sandy Bay Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr James KH Luk (lukkh@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To examine the effectiveness of Integrated

Care and Discharge Support for elderly patients

in reducing accident and emergency department

attendance, acute hospital admissions, and hospital

bed days after discharge. Factors that compromise

its effectiveness were investigated and cost analysis

was performed.

Design: Cohort prospective study.

Setting: Integrated Care and Discharge Support for elderly patients in Hong Kong West Cluster.

Participants: Home-dwelling patients recruited between April 2012 and March 2013 into Integrated Care and Discharge Support for elderly patients in Hong Kong West Cluster.

Results: A total of 1090 older patients were studied.

The Integrated Care and Discharge Support for

elderly patients programme reduced accident and emergency department attendance

by 40% (P<0.001), acute hospital admissions by

47% (P<0.001), and hospital bed days by 31%

(P<0.001) at 6 months after implementation. Improvements in Barthel Index 20

(P<0.001) and Modified Functional Ambulation

Category scale (P<0.001) were observed. Of the patients,

85 (7.8%) died within 6 months of initiation of the

programme. Only 26 (2.4%) older patients required

institutionalisation in residential care homes

within 6 months after the programme. Increasing

age (P=0.025) and high Charlson Comorbidity

Index score (P=0.001) were positive predictors for

accident and emergency department attendance.

A high albumin level (P=0.001) and living alone

(P=0.033) were negative predictors for accident and

emergency department attendance. Of the patients,

310 (28.4%) had no reduction in bed days after the

programme. Increasing age (P=0.025) and number of

medications (P=0.003) were positive predictors for

no reduction in bed days; while higher haemoglobin

level (P=0.034) was a negative predictor. There was

a potential annual cost-saving of HK$22.5 million (approximately US$2.9 million).

Conclusion: The Integrated Care and Discharge

Support for elderly patients programme reduced

accident and emergency department attendance,

acute hospital admissions and hospital bed days,

and was potentially cost-saving. Age, Charlson

Comorbidity Index, albumin level, and living

alone were factors associated with accident and

emergency department attendance. Age, number of

medications, and haemoglobin level were associated

with no reduction in bed days. Further study of the

cost-effectiveness of such programme is warranted.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Integrated Care and Discharge Support for elderly patients (ICDS) reduced accident and emergency department (AED) attendances, acute hospital admissions, and hospital bed days.

- ICDS service was potentially cost-saving and might minimise institutionalisation.

- Age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, albumin level, and living alone were associated with AED attendance.

- Age, number of medications, and haemoglobin levels were associated with no reduction in bed days.

- ICDS programme should be continued in Hong Kong to face the challenges of an increasing older population.

- Further studies are suggested to examine whether AED attendance, acute hospital admissions, and hospital bed days among high-risk older patients can be further reduced by modifying some of the predictive factors identified in this study.

- A more detailed auditing is warranted to show its value in reducing health care costs.

Introduction

‘Revolving door syndrome’ was a phrase coined

by Gordon1 in 1995 to describe the problem of

recurrent return of older people to hospital shortly

after discharge. Readmission is common among

medical patients, especially the elderly population,

and is a poor outcome for the health care system.2 3 A retrospective analysis in 2007 showed the overall

30-day unplanned readmission rate of medical patients was 16.7%.4 A study in Hong Kong West Cluster (HKWC) showed the 28-day readmission

rate for elderly patients discharged from a geriatric

convalescent hospital to be 21.6%.5

To date, different programmes and strategies

have been described to reduce hospital readmission.

These include comprehensive geriatric assessment,

discharge planning, adopting a case manager

approach, post-discharge support services, early

intervention for ad-hoc medical problems, and use of

telephone nursing services.6 7 8 9 10 11 It has been advocated

that in order to achieve better efficacy, any programme

that aims to prevent hospital readmission should

focus on patients at high risk.12 In Hong Kong, the

Hospital Authority (HA) has developed a validated

prediction model named “Hospital Admission Risk

Reduction Program for the Elderly” (HARRPE) to

identify older people at high risk of readmissions.13

The HARRPE score comprises 14 predictors that

are categorised into socio-demographic data, prior

utilisation of accident and emergency department

(AED) and medical ward admission in the past 1

year, co-morbidity, and current index admission. The

higher the HARRPE score (ranges from 0 to 1), the

higher the readmission risk.

In Hong Kong, a pilot Integrated Discharge

Support Program for Elderly Patients (IDSP) was

launched in three hospitals, namely the United

Christian Hospital in 2008, Princess Margaret

Hospital in 2008, and Tuen Mun Hospital in 2009.

The programme targeted patients aged ≥60 years

admitted to these hospitals with a HARRPE score of

≥0.2. It aimed to reduce the risk of AED attendance

and hospital readmission through better discharge

planning and post-discharge support. Preliminary

results showed it successfully reduced AED

attendance, emergency admission, and hospital bed

days.14

In view of the positive results of IDSP and

based on the recommendation of the Elderly

Commission, the Financial Secretary of the Hong

Kong SAR announced in the 2011/2012 budgets that

the Government would allocate additional recurrent

funding to make it a regular service to all districts.

In addition, a new case management approach,

Integrated Care Model (ICM), was added. Such new

programme has been renamed Integrated Care and

Discharge Support for elderly patients (ICDS).

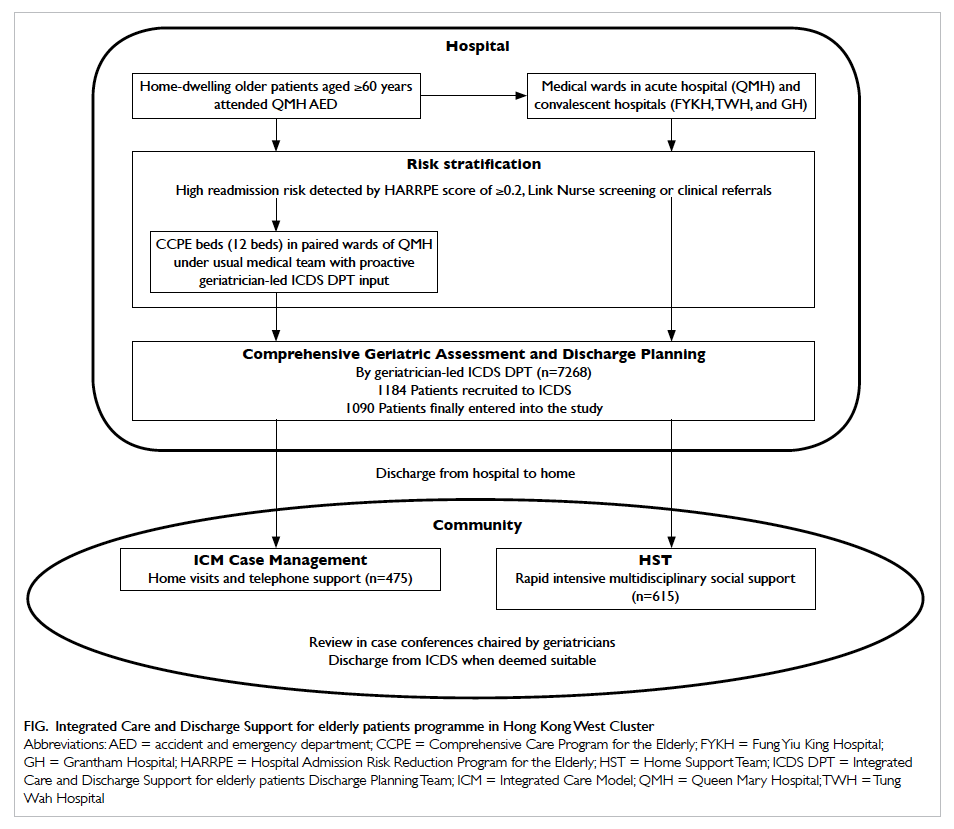

Integrated Care and Discharge Support for

elderly patients in Hong Kong West Cluster

In January 2012, HKWC launched the ICDS and

involves hospital and community components (Fig).

For the hospital component, risk stratification,

comprehensive geriatric assessment, and discharge

planning are performed. Link nurses (who serve

as ‘link’ between in-patients and community

services) work with geriatricians to perform multidimensional

assessments for home-dwelling older

patients aged ≥60 years admitted to medical wards

with HARRPE score of ≥0.2. They also assess elderly

patients by proactive screening. In addition, patients

can be referred to link nurses using a standardised

clinical referral form. The form can be completed

by any member of the clinical team, including

doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and any allied health care

professional. The criteria for clinical referral include

items such as frequent readmission, poor social

support, inadequate care at home, deterioration

in memory, drug compliance problems, repeated

falls, mobility, and functional impairment. Referrers

can also comment about any problem not listed

in the referral form. In HKWC, case recruitment

and discharge planning take place in the medical

wards of the acute hospital, Queen Mary Hospital

(QMH), and three convalescent hospitals, namely

the Fung Yiu King Hospital (FYKH), Grantham

Hospital (GH), and Tung Wah Hospital (TWH).

After assessment, link nurses will, according to need,

allocate patients to either ICM Case Management or

Home Support Team (HST) services (see below). In

order to enhance the care of high-risk older patients

in QMH, a Comprehensive Care Program for the Elderly

(CCPE) area has been established. There are 12 beds

designated as CCPE (6 male and 6 female beds) in

paired wards of QMH. Case recruitment for CCPE

is mainly from the AED. Patients in CCPE are under

the care of the regular medical team with proactive

ICDS multidisciplinary input including geriatric

assessment and discharge planning for appropriate

community support services.

Figure. Integrated Care and Discharge Support for elderly patients programme in Hong Kong West Cluster

In the community component, there are

two important streams, namely the ICM Case

Management and HST service. In ICM Case

Management, each high-risk older patient is

followed up by a case manager for a period of around

3 months following hospital discharge. In HKWC, in

terms of full-time equivalence, two social workers,

one physiotherapist (PT), one occupational therapist

(OT), and half a nurse (advanced practice nurse) take

turns to be a case manager. Case managers provide

post-discharge support to older patients by home

visits and telephone support. They are responsible

for community service coordination and ensuring

patient compliance with planned services and

management. The second stream is the HST service

and is the responsibility of a non-governmental

organisation (NGO) partner. In HKWC, the NGO partner is Aberdeen Kai-fong Association (香港仔坊會). This HST includes nurses, PT, OT, and other allied

health members. They provide rapid and intensive

community support for discharged patients, offering

services such as meal delivery, household cleaning,

respite care, and home assessment and modification.

Case selection and allocation to ICM Case

Management or HST is performed by link nurses

under the supervision of an ICM geriatrician.

Link nurses apply standardised selection criteria

for case allocation. In general, patients with more

complex medical and social problems who require

multidisciplinary intervention by nurses, PT, and/or OT will be allocated to ICM Case Management.

Those who require urgent social services are recruited

into HST. Link nurses, ICM case managers, and the

HST hold weekly multidisciplinary case conferences

chaired by an ICM geriatrician. If needed, referral

for rehabilitation in a geriatric day hospital, fast

track clinic, or early specialist clinic follow-up can

be offered to patients.

Knowledge gaps

The ICDS programme that started in HKWC in 2012

is unprecedented and deserves a large-scale study to

demonstrate its efficacy. Although the aim of ICDS

is not to reduce costs, its value and sustainability can

nonetheless be better justified if this can be achieved.

The objectives of this prospective cohort study

were to investigate whether the ICDS can reduce AED

attendance, acute hospital admissions, and hospital

bed days (acute and convalescence), and to identify

the independent factors that predict its efficacy. In

addition, we wished to determine whether there is

potential for ICDS to reduce health care costs.

Methods

Design and setting

This was a prospective cohort study performed in

four hospitals of HKWC, namely the QMH, FYKH,

GH, and TWH. The study protocol was approved by

the Institutional Review Boards of the University of

Hong Kong and HA HKWC.

Subjects

Our subjects were home-dwelling older patients aged

≥60 years admitted to the general medical wards of

QMH and were recruited into the ICDS programme

by link nurses from 1 April 2012 to 30 March 2013.

Patients were excluded from the analysis if they

died, entered residential care homes for the elderly

(RCHEs), moved out of the cluster, or refused ICDS

services before their first home visit.

Variables

Baseline data included demography, HARRPE score

(if available), mode of feeding, continence status,

presence of pressure sores, and use of an indwelling

urinary catheter, nasogastric tube, or long-term

oxygen. The chief problems at index admission of

ICDS recruitment were noted. In addition, data on

co-morbidities, number of medications, and baseline

blood tests including haemoglobin, albumin, and

creatinine levels were retrieved from the HA

Clinical Management System (CMS). The Charlson

Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to quantify the

burden of co-morbid diseases,15 and quantified

according to International Classification of Diseases

(ICD) coding in CMS.

Cognitive status was assessed on entry to and

discharge from the ICDS programme using the

Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT).16 The patients’

Modified Functional Ambulation Category scale

(MFAC) and Barthel Index 20 (BI-20) status

were also recorded.17 The mortality rate and

institutionalisation rate of patients within 6 months

of intake were calculated.

Outcome measurement

We compared the number of AED attendances,

unplanned acute hospital admissions, and length of

stay (LOS) in both acute and convalescent hospitals

6 months before and 6 months after recruitment.

The index AED attendance and hospital admissions

were counted as pre–6-month outcome. Any

subsequent AED attendance and hospital admission

was included in the post–6-month data. Two

specific outcomes were identified, namely any

AED attendance 6 months after ICDS recruitment,

and no reduction in hospital bed days (acute and

convalescence) 6 months after ICDS. The potential

cost-saving of ICDS was calculated using the existing

cost of AED attendances as well as bed day cost in

acute and convalescent hospitals in HKWC.

Statistical analyses

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 18.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US) was used in statistical analysis. Continuous

variables were expressed as mean ± standard

deviation. Independent t test was used to compare

continuous variables of two different groups. Paired

t test was used to compare the continuous variables

within groups. Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon

signed rank test were used when the continuous

variables could not be assumed to be in normal

distribution. Chi squared test and Fisher’s exact test

were employed to compare categorical variables.

The association between different variables with

any AED attendance and no reduction in bed days

was calculated using univariate logistic regression.

The variables were gender, programmes entered, use

of home oxygen, use of tube feeding, use of a Foley

catheter, presence of wound, BI-20, AMT, MFAC,

CCI, haemoglobin level, albumin level, creatinine

level, and number of medications. Significant factors

detected during univariate analysis were put into

multivariate stepwise backward logistic regression.

Statistical significance was inferred by a two-tailed

P value of 0.05.

Results

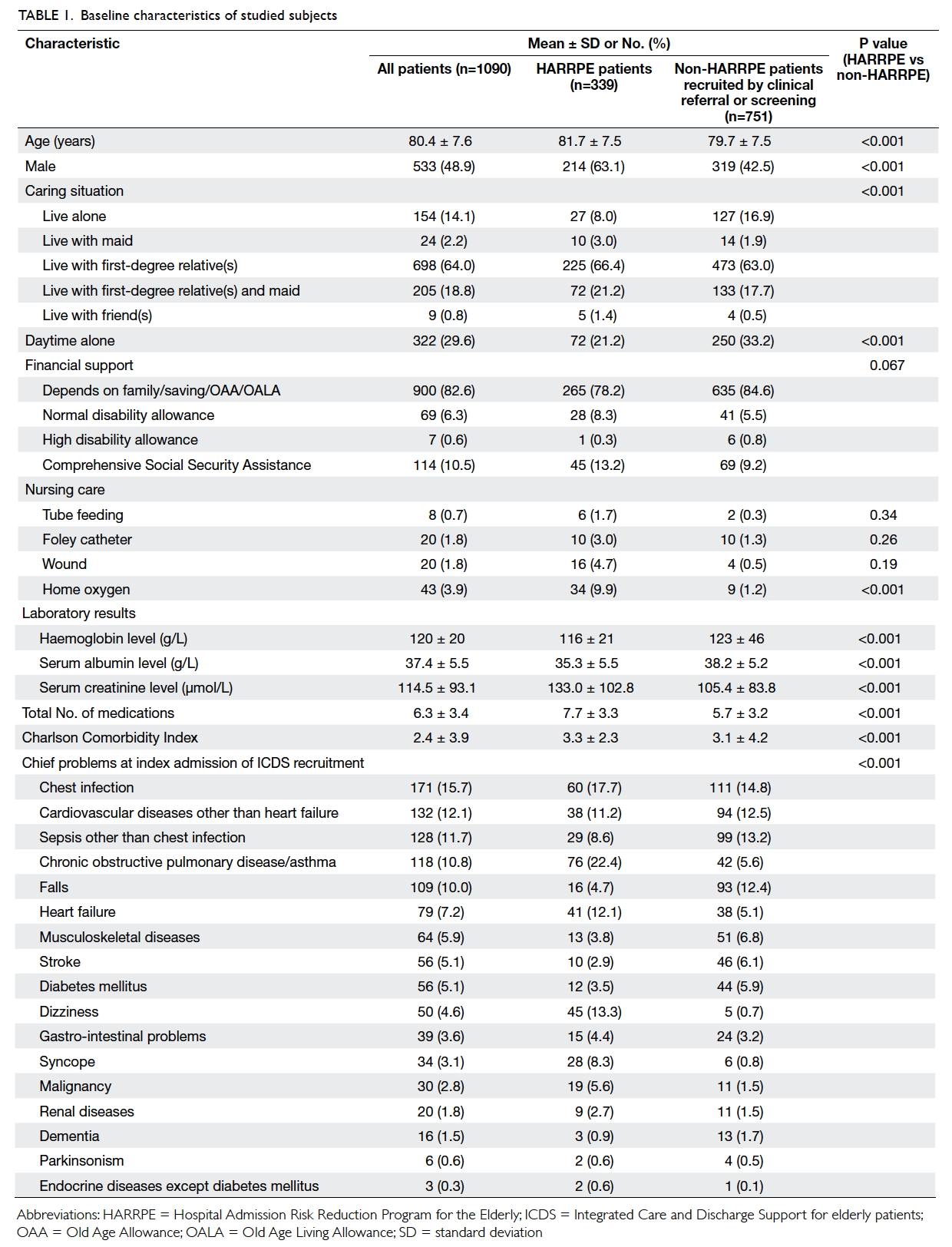

From 1 April 2012 to 30 March 2013, among 7268

hospital discharges, 1184 (16.3%) home-dwelling

older patients aged ≥60 years were recruited to the

ICDS in HKWC. Of these patients, 23 died, 32 were

institutionalised, and 39 refused to join the ICDS

before the first home visit. A total of 1090 patients

entered into the study. The baseline characteristics,

demography, CCI, and chief problems at index

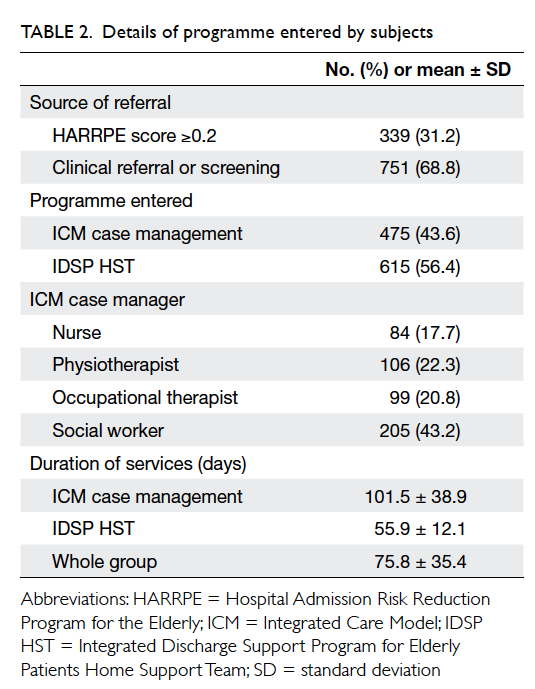

admission of ICDS recruitment are shown in Table 1. Details of the programme entered are shown

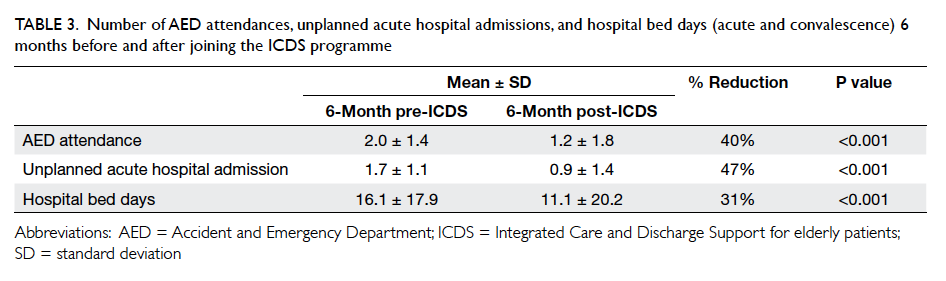

in Table 2. Table 3 illustrates the change in AED

attendances, acute hospital admissions, and bed days

(acute and convalescent hospitals) after joining the

ICDS. Within 6 months of ICDS service, 85 (7.8%)

patients died and only 26 (2.4%) older patients

required institutionalisation in RCHEs. We observed

a 40% reduction in AED attendances 6 months after

initiation of the ICDS compared with 6 months before

(mean, 1.2 vs 2.0 episodes; P<0.001). There was also

a 47% reduction in acute hospital admissions (mean,

0.9 vs 1.7 episodes; P<0.001), and a 31% reduction in

bed days (acute and convalescence) [mean, 11.1 vs

16.1 days; P<0.001] 6 months after joining the ICDS

(Table 3).

Table 3. Number of AED attendances, unplanned acute hospital admissions, and hospital bed days (acute and convalescence) 6 months before and after joining the ICDS programme

There was mild improvement in MFAC and

BI-20 on discharge from the ICDS compared with

the level at entry (MFAC, 6.3 ± 2.2 vs 5.7 ± 1.6,

P<0.001; BI-20, 17.6 ± 4.1 vs 16.5 ± 4.1, P<0.001).

There was no significant change in AMT (8.4 ± 1.7

vs 8.4 ± 2.1; P=0.831).

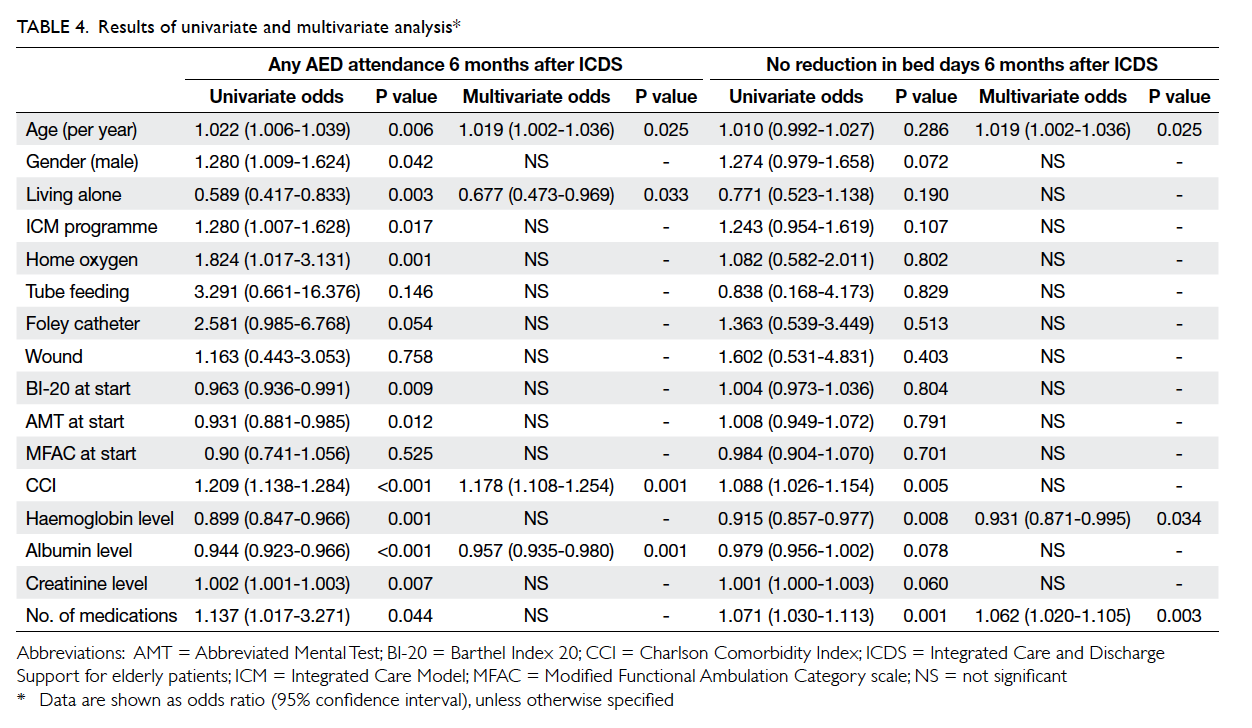

Among 1090 subjects included, 596 (54.7%)

required AED attendance within 6 months of joining

the ICDS. Increasing age (odds ratio [OR]=1.019;

confidence interval [CI], 1.002-1.036; P=0.025)

and high CCI score (OR=1.178; 95% CI, 1.108-1.254;

P=0.001) were independent positive predictors for

AED attendance. A high albumin level (OR=0.957;

95% CI, 0.935-0.980; P=0.001) and living alone

(OR=0.677; 95% CI, 0.473-0.969; P=0.033) were negative

predictors for AED attendance (Table 4). Overall,

310 (28.4%) subjects had no reduction in bed days

when comparing 6 months before and 6 months

after joining the ICDS. Increasing age (OR=1.019;

95% CI, 1.002-1.036; P=0.025) and increasing number of

medications (OR=1.062; 95% CI, 1.020-1.105; P=0.003)

were significant independent positive predictors of

no reduction in bed days; while higher haemoglobin

level (OR=0.931; 95% CI, 0.871-0.995; P=0.034) was a

negative predictor (Table 4).

In HKWC, the cost per patient day was

HK$4461 for an acute-hospital medical bed and

HK$2237 in a convalescent hospital. Each AED

attendance also incurred a cost of HK$877. The

average LOS in an acute medical ward at QMH was

2.4 days. The total number of bed days saved for

acute hospitals were (1.7–0.9) x 1090 x 2.4 = 2093

days. In terms of acute-hospital bed days, the total

cost-saving 6 months following ICDS compared with

6 months before was 2093 x $4461 = HK$9 336 873

(around HK$9.3 million). The total cost-saving for

convalescent-hospital bed days in 6 months was

([16–11] x 1090 – 2093) x $2237 = HK$7 509 609

(around HK$7.5 million). The cost-saving due to

reduced AED attendance was (2.0–1.2) x 1090 x

$877 = HK$764 744 (around HK$0.76 million). The

annual expenditure for the ICDS was HK$12.62

million in total, giving a net cost-saving over 6 months

of (9.3+7.5+0.76) – 12.62/2 = HK$11.25 million.

The potential annual cost-saving was thus HK$11.25

million x 2 = HK$22.5 million (approximately US$2.9

million).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the present ICDS

in HKWC reduces AED attendance, hospital

admissions, and hospital bed days. A local study

has shown that medical patients are in general

prone to institutionalisation following discharge

from hospital.18 This programme appeared to keep

older patients at home as evidenced by the low

institutionalisation rate (2.4%). Nonetheless there

was selection bias as those who required RCHE

admission direct from hospital were excluded from

the study. Hence, ICDS provided intervention in a

group of older patients who had no imminent need of

institutionalisation at the time of hospital discharge.

Different strategies have been described to

reduce readmissions, namely geriatric assessment,

discharge planning, a case manager approach, post-discharge

support services, early intervention for

ad-hoc medical problems, and use of telephone

nursing services.6 7 8 9 10 11 One important element of

success is a targeted approach that provides services

to high-risk patients.12 In 2010, the Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews revealed that a

structured discharge plan tailored to the individual

patient was likely to reduce hospital LOS and

readmission rates for older people.19 The efficacy of a

post-discharge programme that comprises the above

elements was supported by another meta-analysis.20

The ICDS in HKWC comprises all the above elements

with a targeted approach that focuses on high-risk

older patients as identified by their HARRPE score.

In addition, high-risk older patients who were not

identified by a HAPPRE score were recruited as a

result of link nurse screening and clinical referrals in

hospital.

Older patients recruited in the ICDS with

motor and functional problems underwent PT and

OT assessment during home visits. Home exercise

could be taught as appropriate with selected

patients referred to the geriatric day hospital for

rehabilitation. This may help explain why the ICDS

was able to improve the functional and ambulatory

status of patients. We observed no significant AMT

change in our recruited patients upon closure of

ICDS. The ICDS aims at maintaining older patients

in the community during the high-risk period rather

than improving their cognitive function.

Multivariate analysis revealed that increasing

age, low albumin level, and high CCI score were

associated with AED attendance 6 months after

joining the ICDS. This result was very similar to

that of a systematic review of the general risk factors

for preventable readmissions.21 It concluded that

increasing age and poor health as measured by CCI

were associated with high readmission risk.21 Low

serum albumin level is known to associate with

poorer clinical and rehabilitation outcomes in older

patients.22 In this study, patients with advanced

age, low albumin level, and high CCI score were

more likely to attend AED again, even after joining

the ICDS programme. Based on these results, we

may consider adjusting our programme to target

these ‘ultra high-risk’ groups. In this study, living

alone was a protective factor for AED attendance 6

months after joining the ICDS. Although previous

studies showed that living alone was a risk factor

for hospital admission, we found that this group of

patients had significantly fewer AED attendances

after ICDS.23 24 Indeed, age, albumin level and CCI

were all better in the living alone group compared

with those who were not. Living alone remained a

protective factor after multivariate analysis with the

above-mentioned factors adjusted, indicating that

it was an independent predictor by itself. There are

several possible explanations for this observation.

First, older people living at home alone belong to

a selected group who are usually more self-reliant.

With home visits and telephone support by ICDS

case managers or HST, together with geriatrician

backup, they have a dependable team from whom

advice can be sought for ad-hoc problems. On the

contrary, those living with their family might be

less independent. Their health-seeking behaviour is

strongly influenced by family members or carers at

home, who may prompt them or bring them to the

AED for urgent consultations.

In this study, there was a group of patients for

whom there was no reduction in bed days 6 months

after joining the ICDS. These patients were in

more advanced age, with a low haemoglobin level,

and prescribed an increasing number of drugs. It is

possible that the outcome of the ICDS may be further

improved by correcting the anaemia and reducing

polypharmacy in this group of older patients.

There were several limitations in this study. The

study was not a randomised controlled trial. The

ICDS programme is a government-funded service

provided to all suitable older patients in Hong

Kong. Hence, it was practically impossible to have

a control group in the study. Bias in determining

patients’ discharge time might occur as there was no

blinding of treating doctors in the programme. The

decision and time to discharge was subjective and

could have been affected by health care workers who

wanted the programme to demonstrate beneficial

results. The link nurses in the programme could not

perform discharge planning in 100% of the admitted

high-risk patients, as their service was limited on

public holidays and Sundays. In addition, only

16.3% of patients were recruited to the programme

after discharge planning. These factors might

have led to selection bias in the study. Seasonal

variation in hospital admissions among high-risk

older patients might also affect the validity of the

results. Nonetheless, our patients joined the ICDS

at different time points during recruitment and

this, to a certain extent, may minimise the seasonal

variation effect on hospital admission analysis.

Statistically, no adjustment was made for AED

attendance and hospital admissions for patients who

were institutionalised or who died during the post–6-month period. The reduced number of patients

due to deaths was also not considered during the

end of study analysis. The appropriate analysis

would use Cox’s regression, making use of the time

to event (AED attendance), and subjects who died

or were institutionalised during the follow-up period

would be censored and not just excluded from the

analysis. Since the index admission was counted as

the pre-ICDS period, unplanned admission during

the pre-ICDS period would start from ‘one’, putting

the performance during that period at a great

disadvantage when compared with the post-ICDS

period. This study only looked at patients admitted to

hospitals in HKWC. This limited the generalisability

of the results of ICDS in other clusters. The CCI

used in this study was quantified based on ICD

coding in CMS and might have led to undercoding and

consequent underestimation of CCI for patients.

Although there was a potential annual cost-saving

of HK$22.5 million with the ICDS, this was just a

crude calculation and saving based on reduced

bed days: reduced AED attendance provided a

nominal saving. There was no actual reduction in

staff requirements and other expenses as a result of

reduced admissions. In addition, we did not consider

planned readmissions that also contributed to

health care expenditure. The ICDS is designed to

prevent unplanned readmission. The ICM case

managers and HST rarely interfere with planned readmission

for patients, apart from reminding them

to follow the schedule. Thus analysis of the planned

readmissions might not have impacted greatly on our

study findings.

Conclusion

The ICDS reduces AED attendance, unplanned acute

hospital admissions, and hospital bed days in high-risk

older patients. Additional studies are suggested

to determine whether further reductions can be

achieved by modifying some of the predictive factors

identified in this study. A more detailed auditing is

also warranted to demonstrate the value of ICDS in

reducing health care costs.

References

1. Gordon A. ‘Revolving door syndrome’. Elder Care 1995;7:9-10,12.

2. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations

among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program.

N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418-28. Crossref

3. Balla U, Malnick S, Schattner A. Early readmissions

to the department of medicine as a screening tool for

monitoring quality of care problems. Medicine (Baltimore)

2008;87:294-300. Crossref

4. Wong EL, Cheung AW, Leung MC, et al. Unplanned

readmission rates, length of hospital stay, mortality,

and medical costs of ten common medical conditions: a

retrospective analysis of Hong Kong hospital data. BMC

Health Serv Res 2011;11:149. Crossref

5. Luk JK, Tuet OS, Chan FH. Unplanned readmission among

older medical patients discharged from an extended care

hospital. International Hospital Federation Convention;

2001 May 15-18; Hong Kong.

6. Luk JK, Or KH, Woo J. Using the comprehensive geriatric

assessment technique to assess elderly patients. Hong

Kong Med J 2000;6:93-8.

7. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive

discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized

elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999;281:613-20. Crossref

8. Hyde CJ, Robert IE, Sinclair AJ. The effects of supporting

discharge from hospital to home in older people. Age

Ageing 2000;29:271-9. Crossref

9. Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, Singa RM, Shepperd

S, Rubin HR. Comprehensive discharge planning with

postdischarge support for older patients with congestive

heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;291:1358-67. Crossref

10. Steward S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD. Effects of a home-based

intervention among patients with congestive heart

failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch Intern

Med 1998;158:1067-72. Crossref

11. Lim WK, Lambert SF, Gray LC. Effectiveness of case

management and post-acute services in older people after

hospital discharge. Med J Aust 2003;178:262-6.

12. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care

transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled

trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822-8. Crossref

13. Chan S, Kwong P, Kong B, et al. Improving Health of High

Risk Elderly in the Community—the HARRPE. Proceedings

of the Symposium on Community Engagement III “Creating a Synergy for Community Health” 2008; Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Hospital Authority; 2008.

14. Ng MF, Sha KY, Tong BC. Bridging the gap: win-win from

Integrated Discharge Support for Elderly Patients. HA Convention; 2011.

15. Chan TC, Luk JK, Chu LW, Chan FH. Validation study of

Charlson Comorbidity Index in predicting mortality in Chinese older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;14:452-7. Crossref

16. Chu LW, Pei CK, Ho MH, Chan PT. Validation of the

Abbreviated Mental Test (Hong Kong version) in the elderly medical patients. Hong Kong Med J 1995;1:207-11.

17. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The

Barthel index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61-5.

18. Luk JK, Chiu PK, Chu LW. Factors affecting

institutionalization in older Chinese patients after recovery from acute medical illnesses. Arch Geront Geriatr

2009;49:e110-4. Crossref

19. Shepperd S, McClaran J, Phillips CO, et al. Discharge

planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD000313.

20. Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, Brooks D, O’Brien K,

Tregunno D. Effectiveness of early discharge planning in acutely ill or injured hospitalized older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:70. Crossref

21. Vest JR, Gamm LD, Oxford BA, Gonzalez MI, Slawson KM.

Determinants of preventable readmissions in the United States: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2010;5:88. Crossref

22. Luk JK, Chiu PK, Tam S, Chu LW. Relationship between

admission albumin levels and rehabilitation outcomes in older patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;53:84-9. Crossref

23. Arbaje AI, Wolff JL, Yu Q, Powe NR, Anderson GF, Boult

C. Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission

among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist 2008;48:495-504. Crossref

24. Hanania NA, David-Wang A, Kesten S, Chapman

KR. Factors associated with emergency department dependence of patients with asthma. Chest 1997;111:290-5. Crossref