Hong Kong Med J 2015 Jun;21:224–31 | Epub 22 May 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144380

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Hospital Authority audit of the outcome of endoscopic resection of superficial upper

gastro-intestinal lesions in Hong Kong

Anthony YB Teoh, FRCSEd (Gen)1;

Philip WY Chiu, FRCSEd1;

SY Chan, FRCSEd2;

Frances KY Cheung, FRCSEd (Gen)3;

KM Chu, FRCSEd2;

SS Kao, FRCSEd4;

TW Lai, FRCSEd (Gen)5;

CW Lau, FRCSEd6;

Simon YK Law, FRCSEd2;

Canice TL Leung, FRCSEd (Gen)7;

WK Leung, FRCP8;

Daniel KH Tong, FRCSEd (Gen)2;

SH Tsang, FRACS9

1 Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong

Kong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Surgery, Pamela Youde Nethersole Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Department of Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Department of Surgery, Prince Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

6 Department of Surgery, Yan Chai Hospital, Hong Kong

7 Department of Surgery, North District Hospital, Hong Kong

8 Department of Medicine, Queen Marry Hospital, The University of Hong

Kong, Hong Kong

9 Department of Surgery, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Anthony YB Teoh (anthonyteoh@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To review the short-term outcome of endoscopic resection of superficial upper gastro-intestinal lesions in Hong Kong.

Design: Historical cohort study.

Setting: All Hospital Authority hospitals in Hong Kong.

Patients: This was a multicentre retrospective study

of all patients who underwent endoscopic resection

of superficial upper gastro-intestinal lesions between

January 2010 and June 2013 in all government-funded

hospitals in Hong Kong.

Main outcome measures: Indication of the

procedures, peri-procedural and procedural

parameters, oncological outcomes, morbidity, and

mortality.

Results: During the study period, 187 lesions in

168 patients were resected. Endoscopic mucosal

resection was performed in 34 (18.2%) lesions and

endoscopic submucosal dissection in 153 (81.8%)

lesions. The mean size of the lesions was 2.6

(standard deviation, 1.8) cm. The 30-day morbidity

rate was 14.4%, and perforations and severe

bleeding occurred in 4.3% and 3.2% of the patients,

respectively. Among patients who had dysplasia or

carcinoma, R0 resection was achieved in 78% and

the piecemeal resection rate was 11.8%. Lateral

margin involvement was 14% and vertical margin

involvement was 8%. Local recurrence occurred in

9% of patients and 15% had residual disease. The

2-year overall survival rate and disease-specific

survival rate was 90.6% and 100%, respectively.

Conclusion: Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection were introduced in low-to-moderate–volume hospitals with

acceptable morbidity rates. The short-term survival

was excellent. However, other oncological outcomes

were higher than those observed in high-volume

centres and more secondary procedures were

required.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) were introduced in low-to-moderate–volume hospitals with acceptable morbidity rates and excellent short-term survival.

- Other oncological outcomes were higher than those observed in high-volume centres and more secondary procedures were required.

- Better education in recognition of early upper gastro-intestinal neoplasms and pre-ESD workup is required.

- Key personnel who perform ESD in individual hospitals should be identified for further advanced training.

- A minimal level of competence should be established before beginners perform the procedure independently.

Introduction

The use of endoscopic resection in the treatment

of superficial gastro-intestinal neoplasms is gaining

popularity worldwide.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Endoscopic mucosal

resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal

dissection (ESD) are the key endoscopic methods

pioneered in Japan and Korea for resection of

these lesions.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Early gastric or oesophageal

neoplasms are associated with a low rate of lymph

node metastasis and endoscopic resection of these

neoplasms has been shown to be associated with a

low rate of morbidity and high long-term survival.6 7 Nevertheless, the adoption of these techniques

outside high-volume countries has been slow, as

the recognition of early gastric and oesophageal

neoplasms is difficult and the procedures required

for endoscopic resection are technically demanding

and have a long learning curve.8 9 10 11 12 13 14

In Hong Kong, an increased awareness and

recognition of early gastro-intestinal neoplasms

have resulted in greater frequency of diagnosis of

these lesions. Hence advanced endoscopic resection

procedures such as EMR or ESD are also being

performed increasingly. However, the scope of these

services provided by government-funded hospitals

operated by the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong

has not been previously defined. In addition there

are limited data on the outcome of these advanced

endoscopic procedures outside high-volume centres

of Japan and Korea.

The aim of the current study was to perform

a region-wide audit of the short-term clinical

and oncological outcomes of EMR and ESD for

superficial upper gastro-intestinal neoplasms in all

government-funded hospitals in Hong Kong.

Methods

This was a Hong Kong–wide retrospective review

commissioned by the Hospital Authority of Hong

Kong of all patients who underwent EMR or ESD for

superficial upper gastro-intestinal lesions between

January 2010 and June 2013 in 12 government-funded

hospitals. Patients were identified using

the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System

(CDARS) based on their diagnostic and procedural

coding (9th edition of the International Classification

of Diseases). The CDARS is a computer-based

administration database that records all the

diagnostic and procedural coding of admitted

patients. Patient data were retrieved and reviewed

manually through the system. Data were recorded

for indication of the procedures, peri-procedural and

procedural parameters, oncological outcomes, and

morbidity and mortality. The study was performed

according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure

All patients who underwent EMR or ESD of the

oesophagus, stomach, and duodenum were included

in the study. To differentiate these patients from

those that received simple polypectomy, EMR was

defined as the act of performing mucosectomy

with prior injection of a cushioning fluid into the

submucosa to hasten removal of the lesions. It was

acknowledged that EMR could be performed by a

variety of methods but this review did not attempt

to sub-classify patients according to the different

techniques used.1 On the other hand, ESD was

defined as a more refined form of mucosectomy that

involved submucosal injection of a cushioning fluid,

circumferential incision of the mucosa, followed

by dissection of the submucosal tissue to free the

lesion away from surrounding tissue. The type of

endoscopic knives used for mucosal incision and

submucosal dissection were also recorded.

The outcomes of EMR and ESD were assessed clinically and oncologically.

Assessment of clinical outcomes

Compared with conventional polypectomy, ESD is a

technically demanding procedure that is associated

with an increased risk of complications. In particular,

the risk of perforation and bleeding are heightened

in inexperienced operators.13 14 In the current study, intra-procedural and post-procedural complications

were recorded and factors alluding to development

of these complications were also reviewed.

Assessment of oncological outcomes

To determine whether EMR or ESD can provide

adequate oncological clearance for neoplastic

lesions, assessment of long-term survival is essential.

However, since EMR or ESD procedures have been

performed in Hong Kong for only a short period of

time, such assessment was not possible. Thus, the

adequacy of oncological control of EMR or ESD was

based on completeness of resection as judged during

the procedure, presence of margin involvement

(lateral and deep), the need for piecemeal resection,

and recurrence rates. En-bloc resection was defined

as resection of the tumour in one piece. R0 resection

was defined as resection of the tumour with clear

lateral and vertical margins. R1 resection was defined

as microscopic involvement of the margins. R2

resection was defined as macroscopic involvement

of margins as noted during endoscopy. Local

recurrence was defined as recurrent cancer detected

at the primary resection site during follow-up

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy when pathological

review of the ESD specimen revealed no tumour on

the lateral and vertical margins.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were done mainly using

descriptive analysis. The predictors of morbidity

and local recurrences were analysed by multivariate

logistic regression analysis using the following factors:

sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists grading,

presence of neoplastic lesions (adenoma, dysplasia,

carcinoma), ESD performed as a staging procedure,

the need for piecemeal resection, pathological size,

lateral and vertical margin involvement, depth

of pathological invasion, R0 resection, and the

institution volume of ESD. The 2-year overall and

disease-specific survivals were calculated using

the Kaplan-Meier estimator. A two-sided P value

of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses of data were performed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).

Results

During the study period, 187 lesions in 168 patients

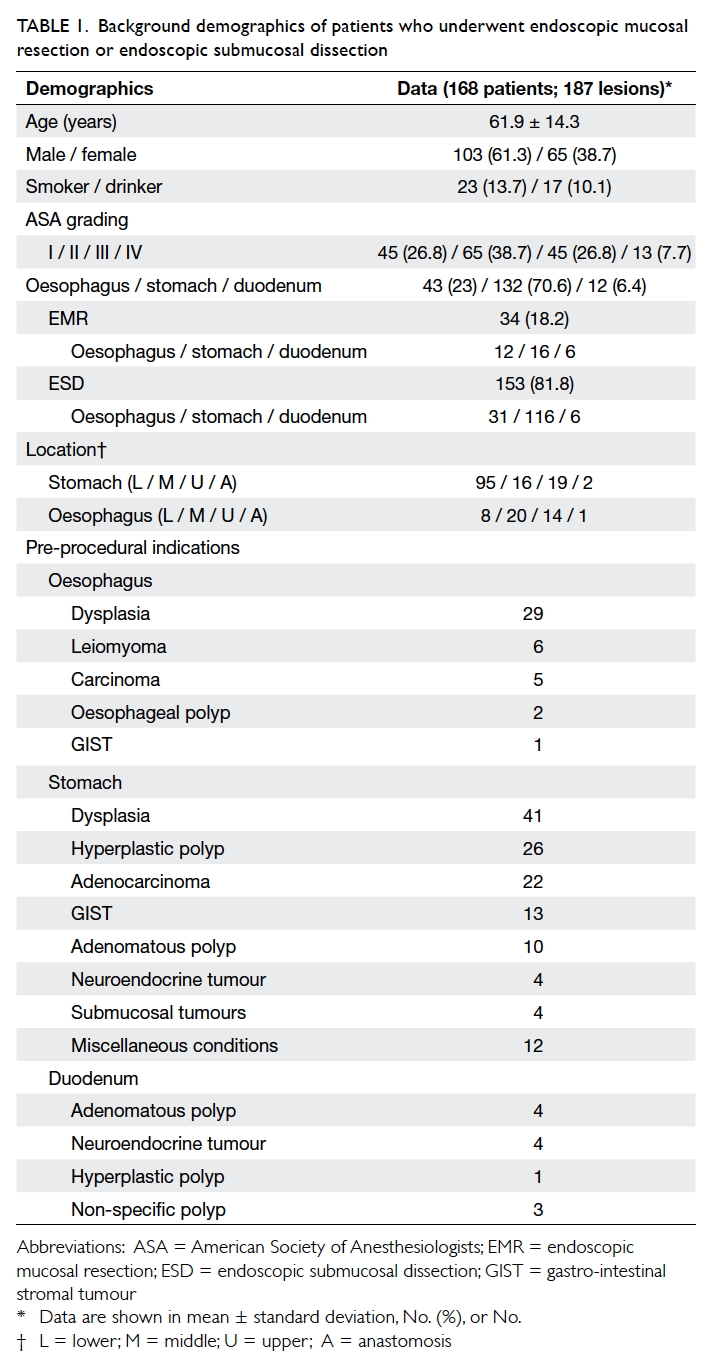

were resected. The patient demographics are shown

in Table 1. The mean (± standard deviation) age of

patients was 61.9 ± 14.3 years and 61.3% were male.

Overall, EMR was performed in 34 (18.2%) lesions

and ESD in 153 (81.8%) lesions for dysplasia or

carcinoma with the majority of lesions located in

the stomach (132 lesions, 70.6%), followed by the

oesophagus (43 lesions, 23%) and the duodenum

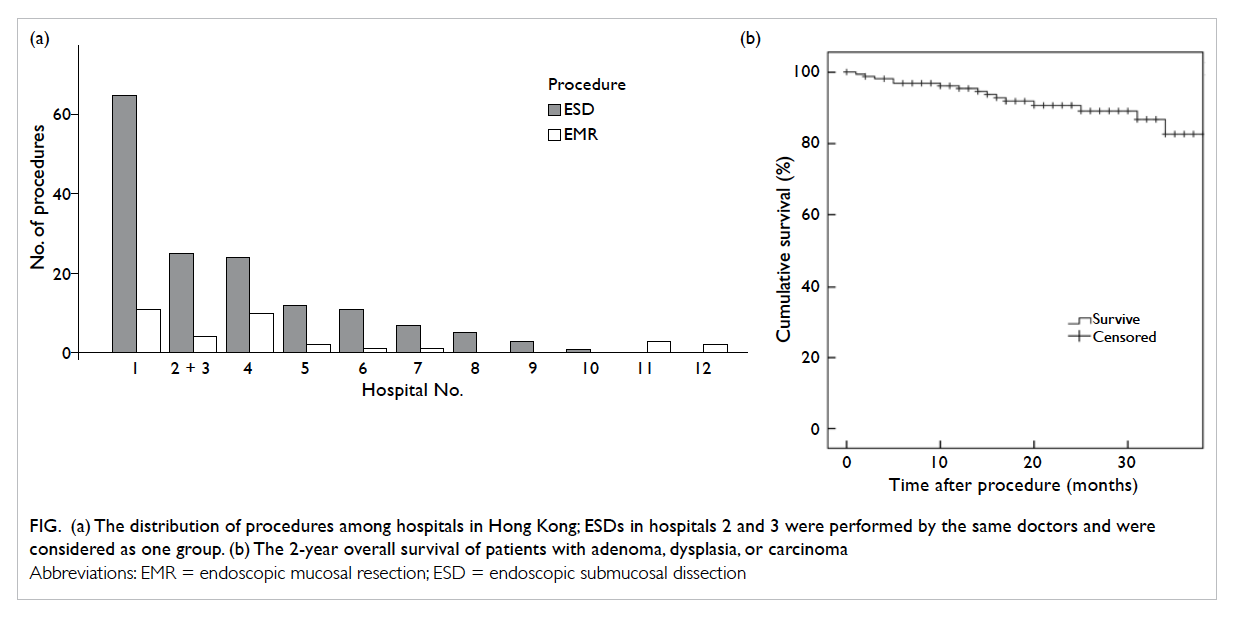

(12 lesions, 6.4%). The distribution in the numbers

of the procedures among various hospitals is shown

in Figure a.

Table 1. Background demographics of patients who underwent endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection

Figure. (a) The distribution of procedures among hospitals in Hong Kong; ESDs in hospitals 2 and 3 were performed by the same doctors and were considered as one group. (b) The 2-year overall survival of patients with adenoma, dysplasia, or carcinoma

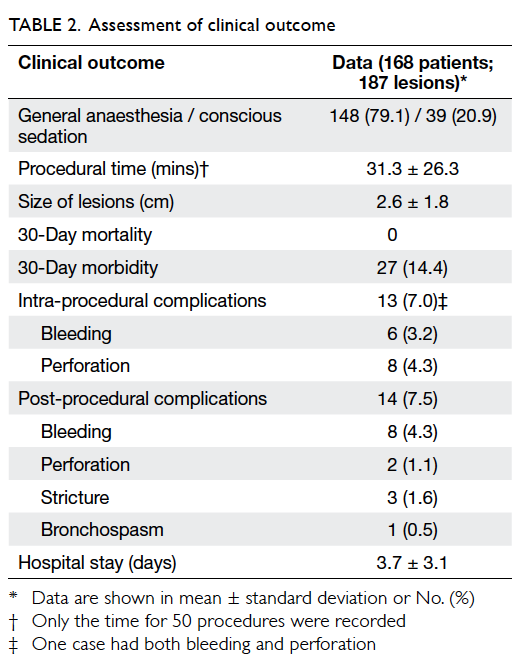

The clinical outcomes of the procedures

are shown in Table 2. General anaesthesia with tracheal intubation was required for the majority of

procedures (n=148, 79.1%). The procedural times

were recorded in 50 (26.7%) procedures only and

were not representative of the actual time required

for the procedures. The mean size of the lesions was

2.6 ± 1.8 cm. The 30-day morbidity rate was 14.4%.

Intra-procedural complications occurred in 13 (7.0%)

procedures, with one procedure having both

bleeding and perforation. Perforations occurred

in eight (4.3%) procedures and all were controlled

with endoscopic clipping. Severe bleeding requiring

endoscopic clipping or transfusion occurred in

six (3.2%) procedures. One procedure required

conversion to open surgery due to uncontrolled

bleeding. Post-procedural complications occurred

in 14 (7.5%) procedures; the most common causes

of which were bleeding (4.3%), stricture formation

(1.6%), and perforations (1.1%). All post-procedural

bleeding and stricture formation were managed

endoscopically. The procedures having perforation

were managed conservatively. No patients had post-procedural

mortality. The mean hospital stay was 3.7

± 3.1 days. Haemoglobin level was checked on the

first post-procedural day in 116 (62%) procedures.

Proton pump inhibitors were prescribed to 171

(91.4%) procedures; of these, 93 (80.2%) were

administered to ESD in the stomach. No difference

in size of lesions, hospital stay, or morbidities was

observed between university– and non-university–affiliated hospitals.

The types of knives used for mucosal incision

included the Dual knife (35.8%; KD-650U, Olympus

Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), the triangular tip knife (14.4%;

KD-640L, Olympus Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), the

needle knife (8%; KD-1L-1, Olympus Co Ltd, Tokyo,

Japan), the insulated tip (IT2) knife (7%; KD-610L,

Olympus Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and the Hybrid

knife (3.7%; ERBE Tübingen, Germany). Knives used

for submucosal dissection included the Dual knife

(48%; KD-650U, Olympus Co Ltd), the insulated tip

(IT2) knife (24.6%; KD-610L, Olympus Co Ltd), the

triangular tip knife (11.2.%; KD-640L, Olympus Co

Ltd), and the Hybrid knife (4.3%; ERBE).

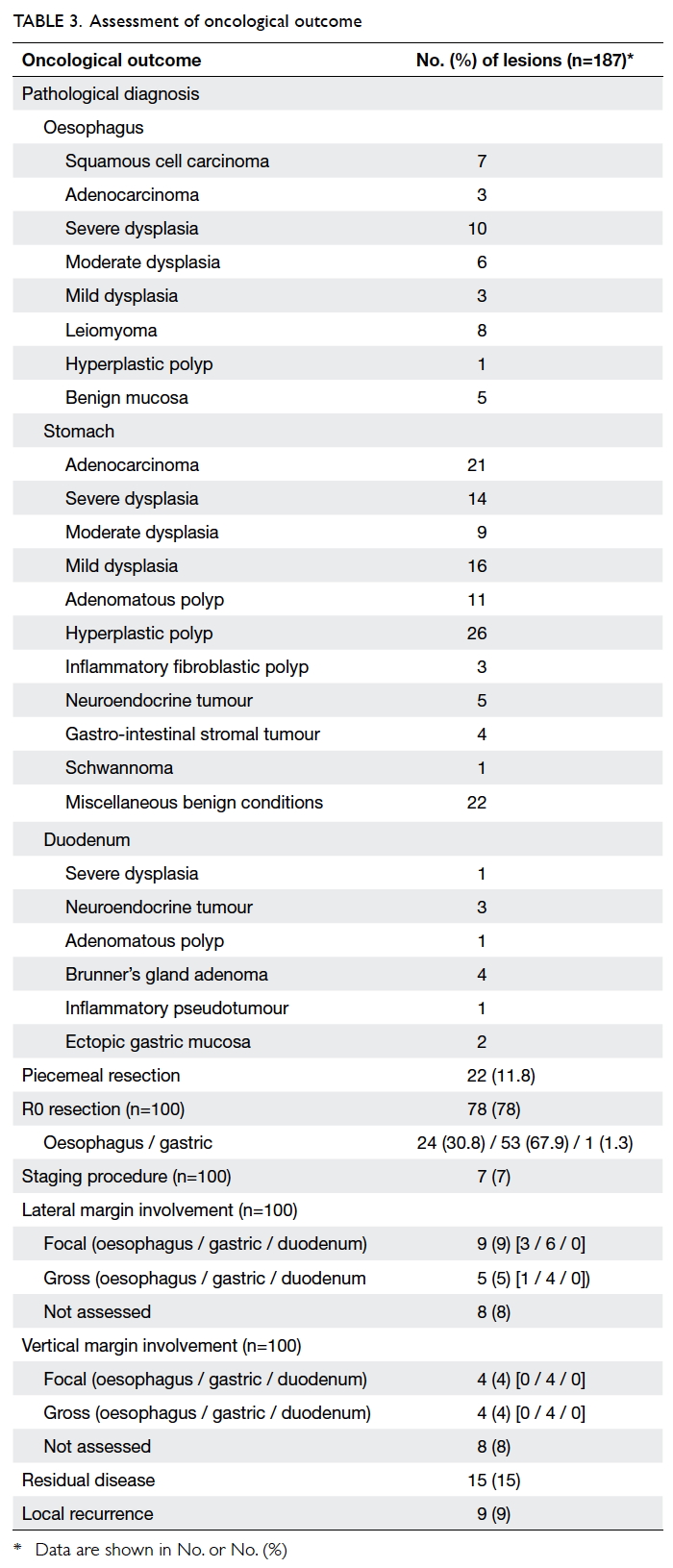

The oncological outcome of the procedures

is shown in Table 3. In 22 (11.8%) lesions, en-bloc

resection was not possible and the lesions had to

be resected in piecemeal. Among patients having

adenoma, dysplasia, or carcinoma (n=100), R0

resection was achieved in 78%. In 7% of the patients,

pre-procedural investigations were inconclusive on

the feasibility of endoscopic resection and ESD was

performed as a staging procedure. Lateral margin

involvement occurred in 14 (14%) procedures and

vertical margin involvement occurred in eight (8%)

procedures. Local recurrences occurred in nine

(9%) patients and five were treated by further ESD.

Residual disease was present in 15 (15%) patients,

four due to failure to complete ESD and 11 due

to margin involvement. Of these 15 patients with

residual disease, complete resection was achieved

in eight during salvage surgical resection, two

patients underwent repeat endoscopic resection,

two underwent radiofrequency ablation, and three

refused treatment. The mean follow-up time of

patients was 20.6 ± 10.8 months and the 2-year overall

survival rate and disease-specific survival rate was

90.6% and 100%, respectively (Fig b). Overall, 38.5%

of patients were followed up for at least 2 years. No

differences in oncological outcomes were observed

between university– and non-university–affiliated

hospitals.

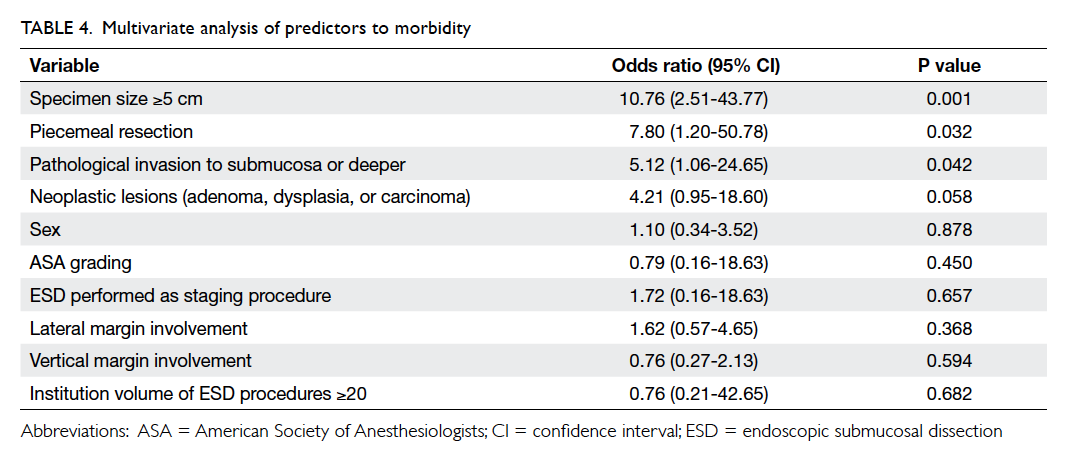

The predictors of morbidity in patients who

received endoscopic resection were then analysed

with multivariate logistic regression (Table

4). Specimen size of ≥5 cm (P=0.001), the need for

piecemeal resection (P=0.032), and pathological

invasion to the submucosa or deeper (P=0.042) were

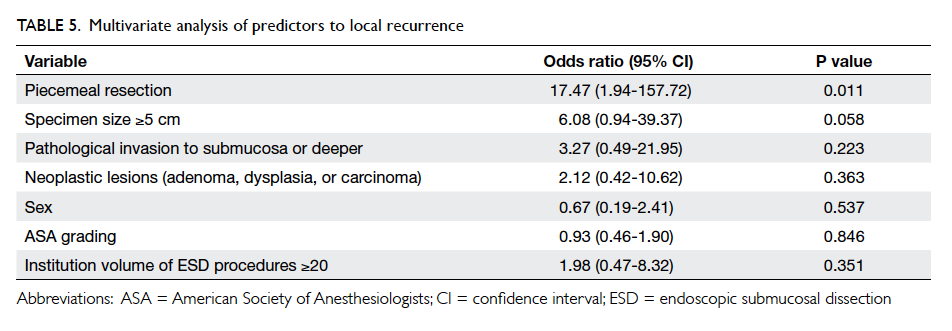

independent predictors of morbidity. The predictors

for local recurrences were also analysed: the need

for piecemeal resection was the only independent

predictor (P=0.011; Table 5).

Discussion

Using a hospital admission database, the outcome

for patients who underwent endoscopic resection of

superficial upper gastro-intestinal neoplasms among

12 government-funded hospitals in Hong Kong was

reviewed. The total number of procedures performed

was higher than expected and the procedures were

associated with a low risk of morbidity. Nonetheless

there may be room for improvement in the

oncological outcome, particularly in terms of rates

of margin involvement and the number of patients

with residual disease. The predictors of morbidity

and local recurrence were in line with those reported

from high-volume centres and the 2-year survival of

patients who had adenoma, dysplasia, or carcinoma

was excellent following endoscopic resection.

The adoption of ESD outside Japan and

Korea has been slow.5 8 15 16 17 18 The reported studies were

mostly small series and the results were variable. In

four European and two South-East Asian studies, the

number of patients included was between 23 and 70,

the en-bloc resection rate ranged from 25% to 100%

and morbidity 0% to 24%. These results contrast

with those obtained from Japan and Korea. In the

stomach, the rate of en-bloc resection was 94.9%

to 95.3% and piecemeal resection was 4.1%. The

risk of bleeding was 1.8% to 16.2% and perforation

was 1.2% to 4.5%. The risk of recurrence was less

than 1% and the 3- and 5-year overall survival rates

were 98.4% and 97.1% respectively.6 7 These results reflect the difficulty of introducing a technically

demanding ESD programme in low-to-medium volume localities outside Japan and Korea.19 The reasons for poorer clinical and oncological outcomes

may be explained by a combination of factors. These

include the early experience and learning curve

issues, technical difficulties leading to the need for

piecemeal resection, and failure to recognise tumour

margins.

The current study is the largest non-Japanese

and non-Korean report on the outcomes of ESD. The

results illustrate that an acceptable en-bloc resection

rate and morbidity rate can be achieved in low-to-medium–volume hospitals. The introduction of

endoscopic resection techniques in Hong Kong is

in its infancy with many challenges similar to those

described in western literature.20 21 22 The emphasis in

our region, however, was not just on the technical

performance of ESD but also the ability to detect

and diagnose these lesions. In 2011, a total of 1101

new cases of gastric cancer were diagnosed in Hong

Kong but the percentage of cases that were amenable

to endoscopic resection is unknown.23 Based on the

findings of this study, the percentages are likely to

have been much less than 10%. This figure contrasts

significantly with those reported from Spain (20%)

and Japan (53%).24 25 Hence, measures to further improve the early diagnosis of upper gastro-intestinal

malignancies are needed. Key personnel

to perform ESD in individual hospitals should be

identified and receive intensive training in screening

endoscopy to improve detection of early lesions.26

These individuals should attend local workshops

and clinical attachments at high-volume centres in

Japan and Korea to acquire such skills. Enhanced

endoscopic imaging systems (narrow band imaging,

flexible spectral imaging colour enhancement, or

autofluorescence imaging) that may improve the ease

of diagnosing early upper gastro-intestinal lesions

should also be obtained by those hospitals interested

in developing the technique and these should be

supported by the government on a regional scale.27 28 29

The use of population-based screening programmes

in our locality may not be justified because of the

moderate incidence of upper gastro-intestinal

cancers, but studies to evaluate screening of high-risk

groups may be justified.30 31 Better recognition of early upper gastro-intestinal neoplasms not only

increases the detection rates but may also allow more

accurate pre-ESD assessment and improve the rates

of margin involvement and oncological outcomes.

It is acknowledged that ESD remains a

technically demanding procedure that is associated

with risk of perforation and bleeding. To master such

skills, the surgeon must be familiar not only with

the ESD procedure, but also with the methods used

to treat complications. In addition, the difficulty of

ESD depends on the organ involved, as well as the

location within that organ.32 33 Thus, in high-volume centres, learning of ESD is usually done in a stepwise

approach, starting from easy small lesions located at

the antrum of the stomach and progressing to more

difficult lesions or lesions located in other parts of

the gastro-intestinal tract.34 35 The number required for mastering the technique is 20 to 40 procedures

in each location. These numbers are unlikely to be

attainable within a short period of time in Hong

Kong and most western countries. Hence, each

locality will need to decide on the most appropriate

training strategy to overcome the learning curve:

this will likely involve intensive training with the use

of animal models, apprenticeship with local experts,

and overseas training in high-volume centres.13 20 24

It may also be beneficial to the region to restrict

the performance of ESD to a few key personnel in

the main institutions and once they are proficient,

involve other endoscopists in the process.

To further improve the outcome of endoscopic

resection of upper gastro-intestinal lesions in

Hong Kong, a number of measures should be

implemented. The establishment of a task force on

endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of early gastro-intestinal

cancers with regular training should

be considered. A local standard in endoscopic

reporting and pathological examination is required

as these assessments of early upper gastro-intestinal

neoplasms are unique and pivotal to guiding

treatment. A ‘best practice’ guideline for performing

ESD and the provision of pre- and post-ESD care

should be established to provide a benchmark for

future audits.

There were a number of limitations to the

current study. First, patients included in the study

were identified using CDARS based on the diagnosis

and procedural coding. There is a risk of unidentified

procedures if they were incorrectly coded. Also,

those procedures that were performed outside the

Hospital Authority hospitals could not be accounted

for. Second, since this is a retrospective review, some

outcome parameters might not have been properly

defined or available for all patients. Finally, since

there is no standardised reporting system in Hong

Kong for ESD or EMR and pathological assessment,

there was a risk of information bias during extraction

of the data.

Conclusion

The introduction of ESD in Hong Kong is still in

its infancy; EMR and ESD were introduced in low-to-moderate–volume hospitals with acceptable

morbidity rates. The short-term survival was

excellent. Nonetheless, other oncological outcomes

were higher than those observed in high-volume

centres and more secondary procedures were

required.

References

1. Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic

mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper

gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4490-8. Crossref

2. Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, et al. Advantage of endoscopic

submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early

gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:877-83. Crossref

3. Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, et al. Endoscopic

submucosal dissection of esophageal squamous cell

neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:688-94. Crossref

4. Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, et al. Outcomes of

endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial

neoplasms in 200 consecutive cases. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2007;5:678-83. Crossref

5. Chiu PW, Chan KF, Lee YT, Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ng EK.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection used for treating early

neoplasia of the foregut using a combination of knives.

Surg Endosc 2008;22:777-83. Crossref

6. Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, et al. Endoscopic

submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale

feasibility study. Gut 2009;58:331-6. Crossref

7. Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, et al. Therapeutic outcomes in

1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early

gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter

study. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:1228-35. Crossref

8. Probst A, Golger D, Arnholdt H, Messmann H. Endoscopic

submucosal dissection of early cancers, flat adenomas,

and submucosal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:149-55. Crossref

9. Dinis-Ribeiro M, Pimentel-Nunes P, Afonso M, Costa

N, Lopes C, Moreira-Dias L. A European case series of

endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric superficial

lesions. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:350-5. Crossref

10. Repici A, Hassan C, Carlino A, et al. Endoscopic

submucosal dissection in patients with early esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma: results from a prospective

Western series. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:715-21. Crossref

11. Probst A, Golger D, Anthuber M, Märkl B, Messmann H.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection in large sessile lesions

of the rectosigmoid: learning curve in a European center.

Endoscopy 2012;44:660-7. Crossref

12. Kakushima N, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Muraki Y,

Tateishi A, Omata M. A learning curve for endoscopic

submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasms.

Endoscopy 2006;38:991-5. Crossref

13. Teoh AY, Chiu PW, Wong SK, Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ng

EK. Difficulties and outcomes in starting endoscopic

submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc 2010;24:1049-54. Crossref

14. Berr F, Ponchon T, Neureiter D, et al. Experimental

endoscopic submucosal dissection training in a porcine

model: learning experience of skilled Western endoscopists.

Dig Endosc 2011;23:281-9. Crossref

15. Rösch T, Sarbia M, Schumacher B, et al. Attempted

endoscopic en bloc resection of mucosal and submucosal

tumors using insulated-tip knives: a pilot series. Endoscopy

2004;36:788-801. Crossref

16. Farhat S, Chaussade S, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic

submucosal dissection in a European setting. A multi-institutional

report of a technique in development.

Endoscopy 2011;43:664-70. Crossref

17. Schumacher B, Charton JP, Nordmann T, Vieth M, Enderle

M, Neuhaus H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of

early gastric neoplasia with a water jet-assisted knife: a

Western, single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc

2012;75:1166-74. Crossref

18. Chang CC, Lee IL, Chen PJ, et al. Endoscopic submucosal

dissection for gastric epithelial tumors: a multicenter study

in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2009;108:38-44. Crossref

19. Chiu PW. Novel endoscopic therapeutics for early gastric

cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:120-5. Crossref

20. Coman RM, Gotoda T, Draganov PV. Training in

endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest

Endosc 2013;5:369-78. Crossref

21. Neuhaus H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the

upper gastrointestinal tract: present and future view of

Europe. Dig Endosc 2009;21 Suppl 1:S4-6. Crossref

22. Deprez PH, Bergman JJ, Meisner S, et al. Current practice

with endoscopic submucosal dissection in Europe: position

statement from a panel of experts. Endoscopy 2010;42:853-8. Crossref

23. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority. Available

from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/. Accessed 11 Feb

2013.

24. Miguélez Ferreiro S, Cornide Santos M, Martínez Moreno

E. Gastric cancer in a Spanish hospital: Segovia General

Hospital (2005-2008) [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol

2012;35:684-90. Crossref

25. Sugano K. Gastric cancer: pathogenesis, screening, and

treatment. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2008;18:513-22, ix. Crossref

26. Yamazato T, Oyama T, Yoshida T, et al. Two years’ intensive

training in endoscopic diagnosis facilitates detection of

early gastric cancer. Intern Med 2012;51:1461-5. Crossref

27. Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T, et al. Early detection of

superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck

region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: a multicenter

randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1566-72. Crossref

28. Jung SW, Lim KS, Lim JU, et al. Flexible spectral imaging

color enhancement (FICE) is useful to discriminate among

non-neoplastic lesion, adenoma, and cancer of stomach.

Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2879-86. Crossref

29. Lee JH, Cho JY, Choi MG, et al. Usefulness of

autofluorescence imaging for estimating the extent of

gastric neoplastic lesions: a prospective multicenter study.

Gut Liver 2008;2:174-9. Crossref

30. Takenaka R, Kawahara Y, Okada H, et al. Narrow-band

imaging provides reliable screening for esophageal

malignancy in patients with head and neck cancers. Am J

Gastroenterol 2009;104:2942-8. Crossref

31. Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, et al. Screening for

gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice.

Lancet Oncol 2008;9:279-87. Crossref

32. Oda I, Odagaki T, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S.

Learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection

of early gastric cancer based on trainee experience. Dig

Endosc 2012;24 Suppl 1:129-32. Crossref

33. Murata A, Okamoto K, Muramatsu K, Matsuda S.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer: the

influence of hospital volume on complications and length

of stay. Surg Endosc 2014;28:1298-306. Crossref

34. Choi IJ, Kim CG, Chang HJ, Kim SG, Kook MC, Bae JM.

The learning curve for EMR with circumferential mucosal

incision in treating intramucosal gastric neoplasm.

Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:860-5. Crossref

35. Gotoda T, Friedland S, Hamanaka H, Soetikno R. A learning

curve for advanced endoscopic resection. Gastrointest

Endosc 2005;62:866-7. Crossref