Hong Kong Med J 2015 Jun;21(3):237–42 | Epub 8 May 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144344

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Mechanism and epidemiology of paediatric finger injuries at Prince of Wales Hospital in

Hong Kong

WH Liu, MB, BS; Johann Lok, MB, ChB; MS Lau, MB, ChB; YW Hung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); Clara WY Wong, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); WL Tse, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery);

PC Ho, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Prince of Wales Hospital,

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WH Liu (liuwinghong@yahoo.com.hk)

This paper was presented at the 27th Annual Congress of the Hong Kong

Society for Surgery of the Hand, 15-16 March 2014, Hong Kong.

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the mechanism and

epidemiology of paediatric finger injuries in Hong

Kong during 2003-2005 and 2010-2012.

Design: Comparison of two case series.

Setting: University-affiliated teaching hospital, Hong Kong.

Patients: This was a retrospective study of two cohorts of

children (age, 0 to 16 years) admitted to Prince of

Wales Hospital with finger injuries during two 3-year

periods. Comparisons were made between the

two groups for age, involved finger(s), mechanism

of injury, treatment, and outcome. Telephone

interviews were conducted for parents of children

who sustained a crushing injury of finger(s) by door.

Results: A total of 137 children (group A) were

admitted from 1 January 2003 to 31 December

2005, and 109 children (group B) were admitted

from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2012. Overall,

the mechanisms and epidemiology of paediatric

finger injuries were similar between groups A and

B. Most finger injuries occurred in children younger

than 5 years (group A, 56%; group B, 76%) and in

their home (group A, 67%; group B, 69%). The most

common mechanism was crushing injury of finger by

door (group A, 33%; group B, 41%) on the hinge side

(group A, 63%; group B, 64%). The right hand was

most commonly involved. The door was often closed

by another child (group A, 37%; group B, 23%) and

the injury often occurred in the presence of adults

(group A, 60%; group B, 56%). Nailbed injury was the

commonest type of injury (group A, 31%; group B,

39%). Fractures occurred in 24% and 23% in groups

A and B, respectively. Traumatic finger amputation

requiring replantation or revascularisation occurred

in 12% and 10% in groups A and B, respectively.

Conclusions: Crushing injury of finger by door

is the most common mechanism of injury among

younger children and accounts for a large number

of hospital admissions. Serious injuries, such as

amputations leading to considerable morbidity,

can result. Crushing injury of finger by door occurs

even in the presence of adults. There has been no

significant decrease in the number of crushing

injuries of finger by door in the 5 years between the

two studies despite easily available and affordable

preventive measures. It is the authors’ view that

measures aimed at promoting public awareness and

education, and safety precautions are needed.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Similar to other countries, crushing injury of finger by door was the most common cause of paediatric finger injuries in Hong Kong.

- Although many preventive measures are available and easily accessible at low cost, there were no significant differences in injury mechanism and epidemiology between 2003-2005 and 2010-2012.

- Paediatric crushing injury of finger by door can occur even in the presence of adults. Reinforcement of public education on the use of safety measures, including door modification and precautions in the home, should be conducted to prevent such injuries.

Introduction

Injuries to the hand and fingers are extremely

common in children, yet they can have a significant impact on a child’s growth and development. Fingers

are used to explore surroundings and perform daily

activities such as playing, eating, and homework.

Restricting children from these activities due to

injuries can have immediate short- and long-term

detrimental effects on the function of the hand,

psychological wellbeing, and quality of life of the

children. A 10-year review on the psychological

impact on children and adolescents with finger or

hand injuries noted that “Hand injuries are common

and loss of a dominant hand or opposition is most

important [sic]. Self-esteem and skill are associated

with hand sensation, appearance, and functions.”1

Studies by Al-Anazi2 and Doraiswamy3 have identified crushing injury of finger(s) by door as the

main cause of finger injuries in children. However,

there has been no local study to identify the main

cause of finger injuries in Hong Kong. In 2007,

Lau and Ho presented data on the epidemiology of

childhood finger injuries (unpublished data; Lau M,

Ho PC. 20th Annual Congress of the Hong Kong

Society for Surgery of the Hand, Hong Kong, 2007)

that supported the findings in other cities. Similar

to Al-Anazi2 and Doraiswamy,3 Lau and Ho found

that crushing injury of finger by door was the most

common cause of paediatric finger injuries from

2003 to 2005, and recommended various preventive

measures.

The present study aimed to compare the

previous set of data from 2003 to 2005 reported by

Lau and Ho with more recent data obtained from

2010 to 2012. By comparing the epidemiology and

mechanisms of finger injuries among local Hong

Kong children, we aimed to determine whether there

have been any significant changes over the past 5

years.

Methods

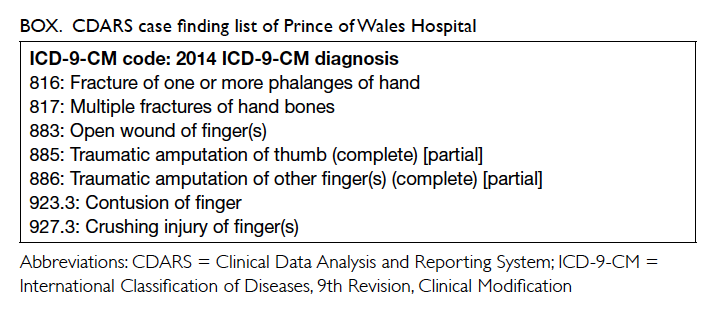

Data of patients admitted to Prince of Wales

Hospital from 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2005

(group A) and from 1 January 2010 to 31 December

2012 (group B) were retrieved using the Clinical

Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS) of the

Hospital Authority’s Clinical Management System.

Children aged 0 to 16 years, and with at least one

of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th

Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes

listed in the Box among the top three diagnoses were

included in the analysis.

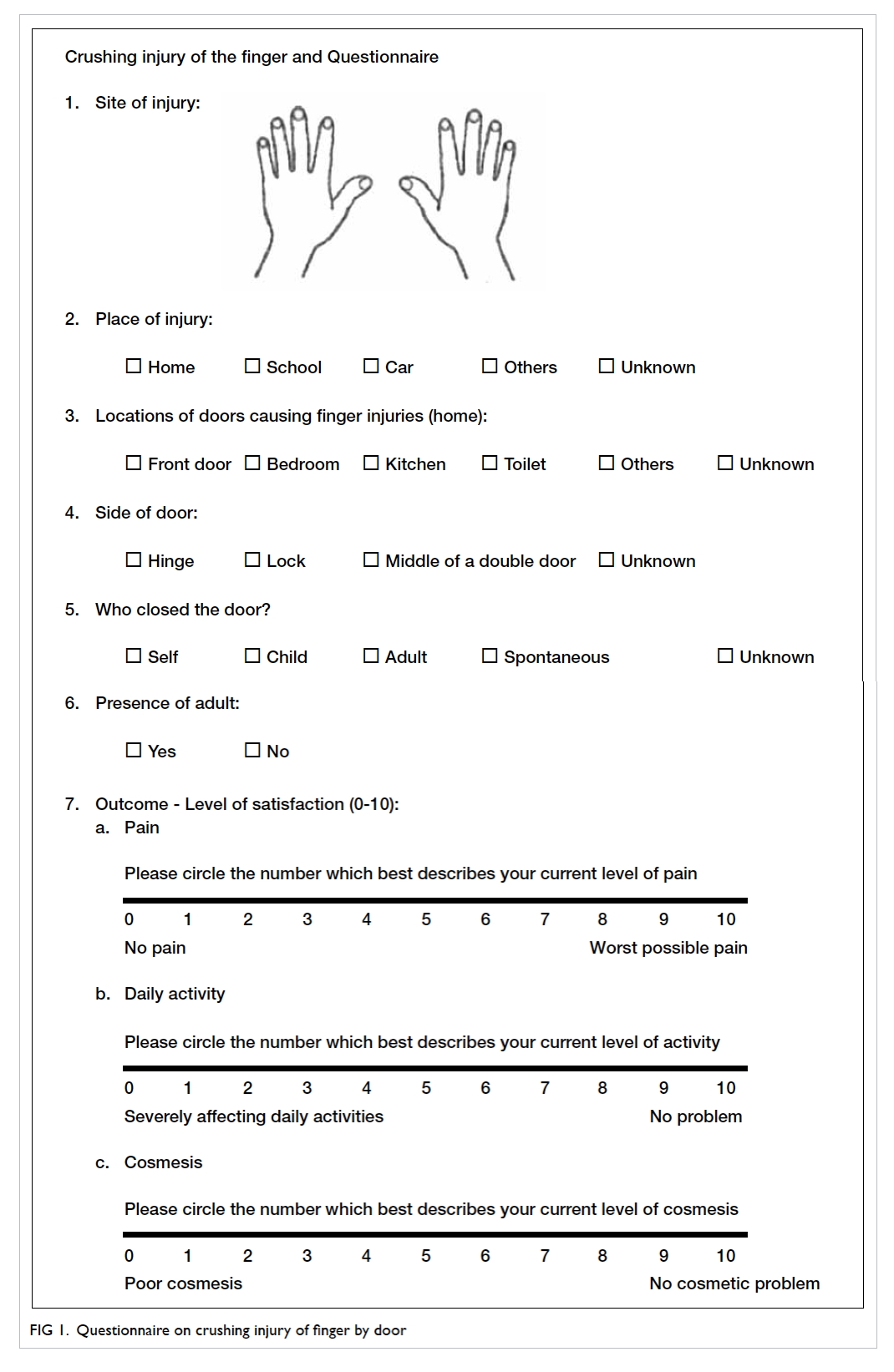

Discharge summaries of all patients were

reviewed to identify the mechanisms of finger

injuries. For children in whom the mechanism was

not immediately discernable from the discharge

summary, further clarifications were obtained by

telephone interviews with the child’s parents, which

were conducted in 2006 for group A and in 2013 for

group B. For children in whom crushing injury of

finger(s) were due to closing doors, additional data

were collected by telephone interviews with their

parents using a specifically designed questionnaire

(Fig 1).

Results

Group A consisted of 140 children who presented

with finger injury to Prince of Wales Hospital from

1 January 2003 to 31 December 2005. Three children

from this group were excluded due to coding error.

Group B comprised 109 children who presented

from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2012. No

children from this group were excluded.

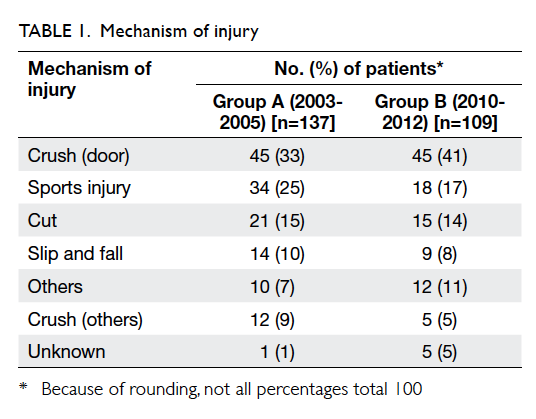

In both groups, crushing injury of finger by

door was the most common cause of injury—45

(33%) in group A and 45 (41%) in group B—followed

by sports injury, cut, and slip and fall (Table 1).

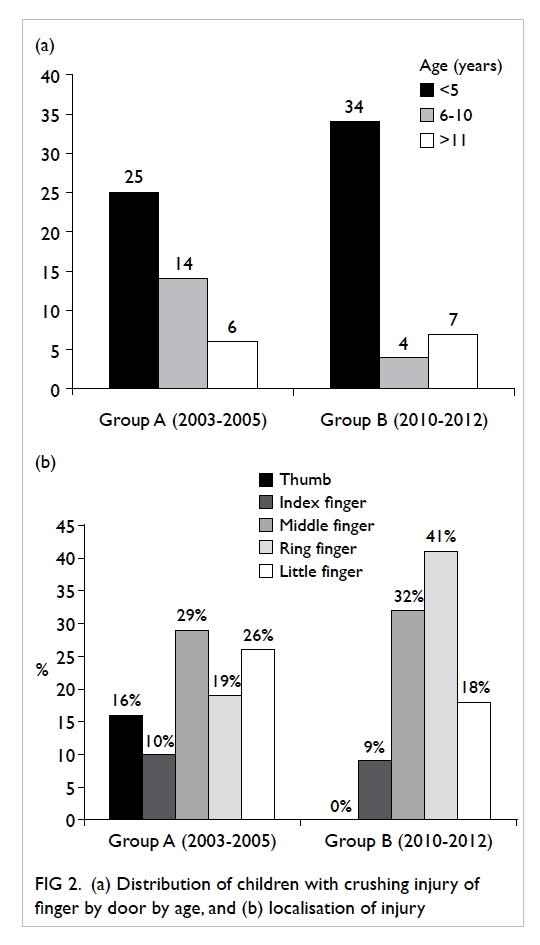

Among children with crushing injury of finger by

door, younger children were the most commonly

injured (Fig 2a). The male-to-female ratio was 1:1.25

in group A and 1.37:1 in group B.

Figure 2. (a) Distribution of children with crushing injury of finger by door by age, and (b) localisation of injury

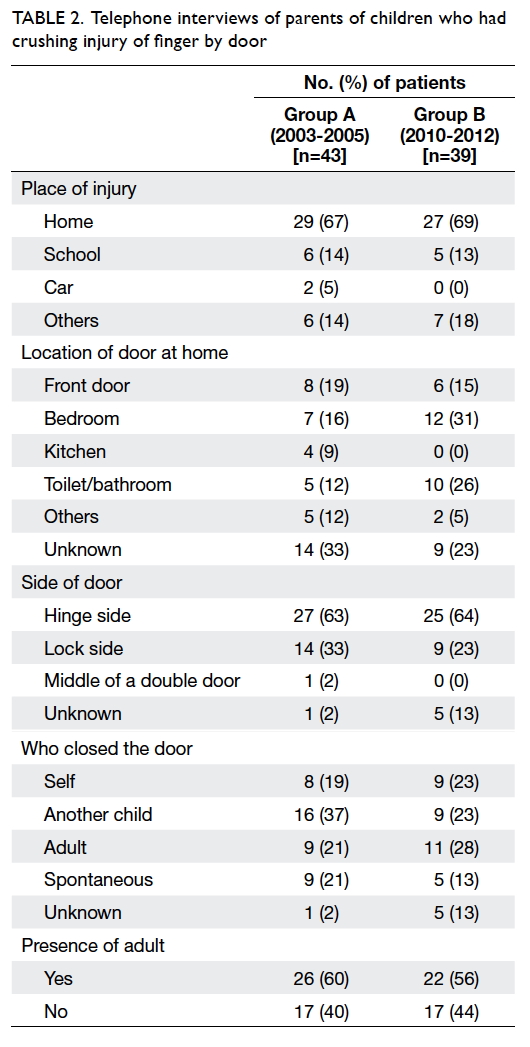

In the telephone interviews conducted with the

parents of the 45 children who had crushing injury

of finger by door, parents of two children in group A

and six children in group B could not be contacted.

Overall, all the parameters measured were similar

between the periods 2003-2005 and 2010-2012.

In both groups, most of the fingers involved were

from the right hand, with the middle, ring, and little

fingers being more commonly affected than the

other fingers (Fig 2b).

Most of the injuries occurred at home—29

(67%) in group A and 27 (69%) in group B. At home,

fingers were most frequently crushed at the hinge

side of the door—27 (63%) in group A and 25 (64%)

in group B—followed by the lock side and the middle

of a double door. The doors were frequently closed

by another child—16 (37%) in group A and 9 (23%) in

group B and, in more than half of the cases, occurred

even in the presence of adults—26 (60%) in group A

and 22 (56%) in group B (Table 2).

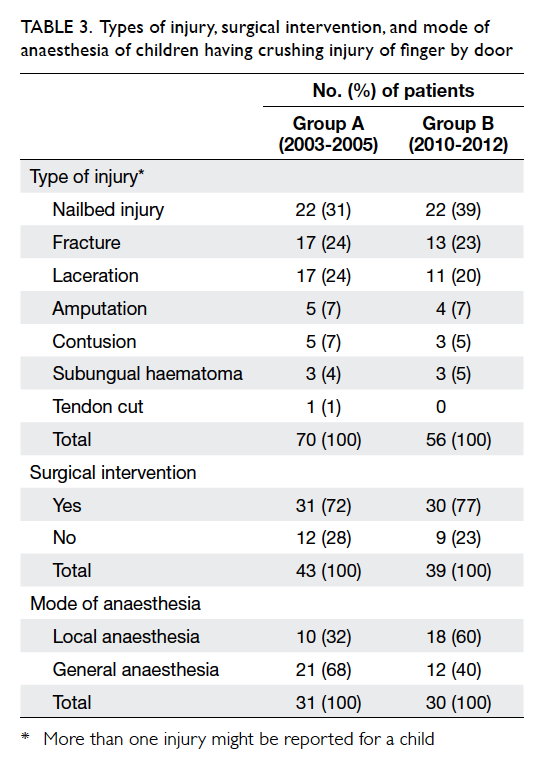

The types of injury and their relative

frequencies were compared between the groups

(Table 3). Among the more common injuries were: nailbed injury—22 (31%) in group A and 22 (39%) in

group B; fracture—17 (24%) in group A and 13 (23%)

in group B; and laceration—17 (24%) in group A and

11 (20%) in group B. Most of the children in both

group A (31 [72%]) and group B (30 [77%]) required

operation. Among the 31 operations in group A, 21

(68%) were performed under general anaesthesia. By

contrast, only 12 (40%) of the 30 operations in group

B involved general anaesthesia.

Table 3. Types of injury, surgical intervention, and mode of anaesthesia of children having crushing injury of finger by door

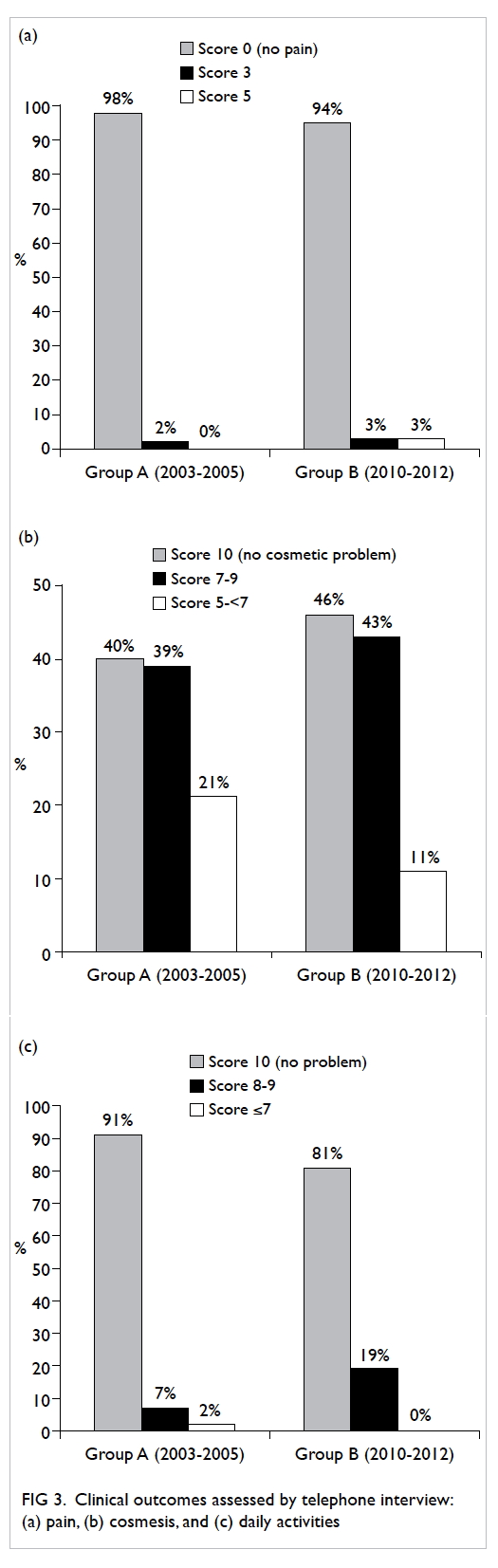

Clinical outcomes were assessed when the

telephone interviews were conducted, ie, in 2006

for group A and in 2013 for group B. Most children

had a good recovery following treatment. Overall,

42 (98%) of children in group A and 37 (94%) of

children in group B reported no pain. Only minor

cosmetic problems prevailed in most children, with

34 (79%) in group A and 35 (89%) in group B rating

their current level of cosmesis over 7 out of 10 (score

10 = no cosmetic problem). The injuries had minimal

adverse effects for most children, with 42 (98%) in

group A and 39 (100%) in group B rated their daily

activities with a score over 8 (score 10 = no problem)

[Fig 3].

Figure 3. Clinical outcomes assessed by telephone interview: (a) pain, (b) cosmesis, and (c) daily activities

However, five (12%) children in group A and

four (10%) children in group B had crushing injury

of finger by door resulting in finger amputation.

Altogether seven children in groups A and B

received replantation or revascularisation, one child

underwent open reduction and fixation only, and

one had a failed replantation due to failure to locate

the arteries intra-operatively.

In group A, one child developed thrombosis

following replantation of the right ring finger,

requiring a subsequent revascularisation procedure

3 days later. This was complicated by hooknail

deformity 1 year post-replantation and was

subsequently treated by further reconstructive

procedures. The levels of satisfaction in terms of

appearance and daily function at final follow-up

were rated 5 and 3 (out of 10, with 10 means no

cosmetic problem and no problem in daily activities),

respectively.

Discussion

Crushing injury of finger by door is common. The

true incidence of this type of injury is likely to be

higher, as our data were limited to public hospitals

so relied on the correct entry of ICD-9-CM codes

into the CDARS. Data from the accident and

emergency department and private practitioners

were not analysed. Furthermore, many minor

injuries might have been managed at home and not

reported.

Crushing injury of finger by door is not just

a local problem. Studies from Saudi Arabia and

Glasgow showed that this type of injury accounted

for most childhood fingertip injuries in these areas.2 3 These injuries consistently occurred at home, with

the involved finger being frequently crushed at the

hinge side of doors. Younger children were mostly

affected. The similarity in epidemiology between

the overseas data and our local data can help with

recommendations for suitable door safety devices.

In this study, we identified that crushing injury

by door was the major cause of paediatric finger

injuries leading to hospital admission in both 2003-2005 and 2010-2012. Although most children were

satisfied with the level of pain, cosmesis, and daily

function of the injured digit at their final follow-up

after treatment, serious injuries involving fractures

and amputations occurred in a minority of patients.

In addition to the surgical intervention and long-term

hospitalisation required, these injuries could

further lead to detrimental effects on the children’s

growth and development.

Our study showed the presence of adults did

not reduce the rate of these accidents, since most

occurred even in the presence of an adult. This

highlights the need for other preventative measures.

Many types of safety devices are easily

available and affordable in Hong Kong. As the hinge

side of doors is the most common side for fingers

to be crushed, finger guard devices can be installed

to prevent fingers being trapped in the opposing

surfaces. Triangular-shaped rubbers, plastic or

wooden stoppers can be inserted at the bottom of

a door to prevent spontaneous closure. Magnets

applied to the back of a door and its opposing wall

surface present another equally effective and simple

method of preventing unintended door closures.

Dampers can be set up to reduce the speed of closing

doors, thereby decreasing the force exerted on

trapped fingers. The use of automatic doors should

be avoided.

Yet, despite the easy availability and

accessibility of these safety devices, there has been

no significant change or improvement in terms of

incidence and morbidity of children with crushing

injury of fingers by door admitted to Prince of Wales

Hospital in the 5-year period between 2003-2005

and 2010-2012. Thus, we should promote public

awareness about this type of injury and provide

more educational programmes on safety precautions

in order to reduce the incidence of crushing injury

of finger by door.

Conclusions

Crushing injury of finger by door accounts for the

most common cause of paediatric finger injury

requiring hospitalisation in Hong Kong. These

injuries frequently result in hospital admission and

surgical intervention, with considerable morbidity

and high treatment cost. Crushing injury of finger by

door occurs even in the presence of adults. Despite

the easily available and affordable preventative

measures in Hong Kong, our comparison revealed

no significant difference in the incidence, nature, and

severity of these domestic injuries between the years

2003-2005 and 2010-2012. Thus, it is our view that

more effort should be invested into raising public

awareness and education about these preventable

injuries and to promote prevention measures.

References

1. Stoddard F, Saxe G. Ten-year research review of physical

injuries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:1128-45. Crossref

2. Al-Anazi AF. Fingertip injuries in paediatric patients—experiences at an emergency centre in Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc 2013;63:675-9.

3. Doraiswamy NV. Childhood finger injuries and safeguards. Inj Prev 1999;5:298-300. Crossref