DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134208

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Helicobacter pylori–negative gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: magnifying endoscopy findings

TT Law, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery);

Daniel Tong, MS, PhD;

Sam WH Wong, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery);

SY Chan, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery);

Simon Law, MS, FRCSEd

Division of Esophageal and Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Simon Law (slaw@hku.hk)

Abstract

Gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue

lymphoma is uncommon and most patients

have an indolent clinical course. The clinical

presentation and endoscopic findings can be

subtle and diagnosis can be missed on white light

endoscopy. Magnifying endoscopy may help identify

the abnormal microstructural and microvascular

patterns, and target biopsies can be performed.

We describe herein the case of a 64-year-old

woman with Helicobacter pylori–negative gastric

mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

diagnosed by screening magnification endoscopy.

Helicobacter pylori–eradication therapy was given

and she received biological therapy. She is in clinical

remission after treatment. The use of magnification

endoscopy in gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid

tissue lymphoma and its management are reviewed.

Introduction

Primary extranodal low-grade B cell lymphoma of

the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALToma)

of stomach is uncommon. The clinical presentation

is variable and there is no endoscopic hallmark.

Magnifying endoscopy (ME) may help in the

diagnosis of gastric MALToma. Herein we report

the case of a patient who had gastric MALToma

diagnosed by ME.

Case report

A 64-year-old woman had a history of cancer of

alveolus that was in remission. She was considered

at increased risk of developing squamous cell

carcinoma of the upper aero-digestive tract;

therefore, she was referred to us for endoscopic

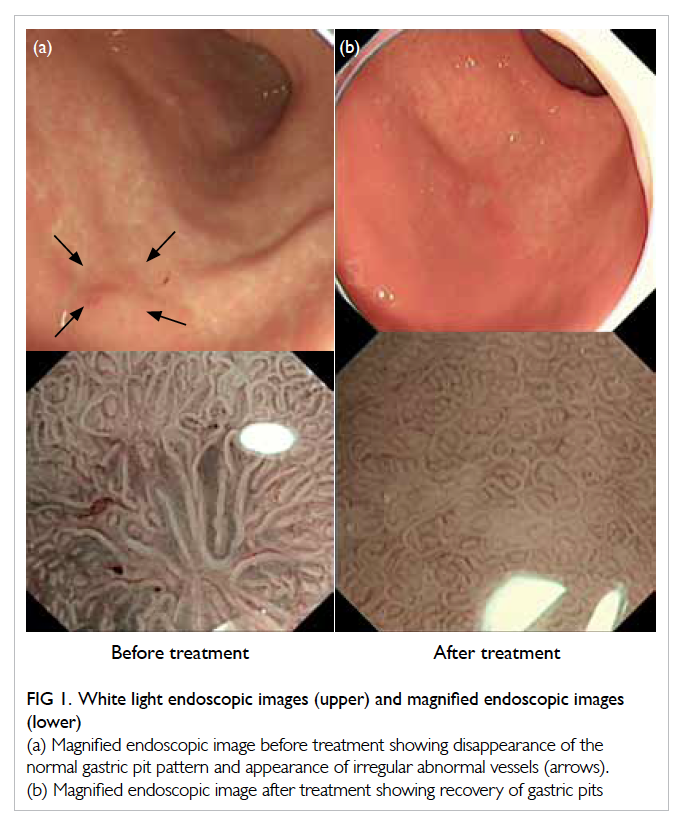

screening in May 2012. On white light endoscopy,

a well-demarcated erythematous zone measuring

3 cm in size was identified at the distal greater

curvature of the stomach (Fig 1a). To further

delineate this suspicious lesion, ME combined with

narrow-band imaging (NBI) was used. Magnifying

endoscopy was performed with a zoom endoscope

(GIF-Q260Z; Olympus Hong Kong and China Ltd,

China) which has a magnifying power of 80 times.

The tip of the endoscope was mounted with a

transparent cap for the purpose of focusing. Under

ME in combination with NBI, a non-structural area,

ie, complete or almost-complete disappearance of

gastric crypt epithelium and abnormal mucosal

capillary pattern was identified (Fig 1a). Biopsy of

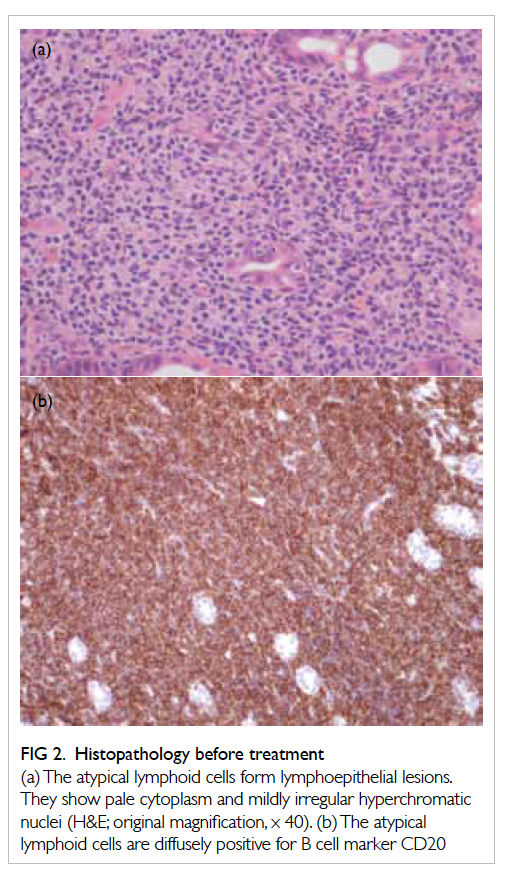

the suspicious zone revealed atypical lymphoid

cells with lymphoepithelial lesion formation.

Immunohistochemical stains confirmed that the

atypical lymphoid cells were positive for B cell

marker CD20 (pan-B-cell marker: L26, Dako, UK),

and negative for T cell markers CD3 and CD5 (Fig

2). Helicobacter pylori was not found. These findings

were consistent with gastric MALToma. Whole-body

positron-emission tomography scan did not

show abnormal uptake in the stomach and the rest

of body.

The patient was empirically treated with H

pylori–eradication therapy (esomeprazole 20 mg twice

daily, amoxicillin 1 g twice daily, and clarithromycin

500 mg twice daily for 1 week). She was then treated

with four doses of rituximab (weekly for 4 weeks);

this treatment was completed in June 2012. Repeated

endoscopy and biopsy at 4 weeks after treatment

showed a residual focus of MALToma. Radiotherapy

(30 Gy) was subsequently given for improved local

control in view of partial response to rituximab,

which was completed in December 2012. Endoscopy

performed 6 weeks after completion of radiotherapy

showed complete response, ie, recovery of gastric pit

pattern under ME (Fig 1b).

Figure 1. White light endoscopic images (upper) and magnified endoscopic images (lower)

(a) Magnified endoscopic image before treatment showing disappearance of the normal gastric pit pattern and appearance of irregular abnormal vessels (arrows). (b) Magnified endoscopic image after treatment showing recovery of gastric pits

Figure 2. Histopathology before treatment

(a) The atypical lymphoid cells form lymphoepithelial lesions. They show pale cytoplasm and mildly irregular hyperchromatic nuclei (H&E; original magnification, x 40). (b) The atypical lymphoid cells are diffusely positive for B cell marker CD20

Discussion

Gastric MALToma is uncommon and accounts

for 1% to 5% of all gastric cancers. Isaacson and

Wright1 first reported a low-grade gastric lymphoma

in 1983. Lymphoid tissue is absent in the normal

gastric mucosa. Helicobacter pylori is believed to

play a causative role in the development of gastric

MALToma.2 Gastric lymphoid tissue is acquired in

response to local infection by H pylori, and there is

a strong association between H pylori infection and

gastric MALToma. Approximately 90% of gastric

MALTomas are H pylori positive. Pathogenesis of

gastric MALToma is a multistep process; H pylori

infection causes chronic gastritis, which leads to

immunological reaction with formation of lymphoid

follicles and, subsequently, to genetic abnormalities

and malignant transformation. Eradication of H

pylori may lead to remission in 50% to 90% of cases.3 4

Most patients with gastric MALToma have an

indolent clinical course; the 5-year overall survival

after H pylori eradication has been reported to be

82% to 96%.5 6

The presentation of MALToma is variable.

Patients may present with non-specific symptoms

such as epigastric pain, vomiting, and weight loss.

Endoscopy with biopsy is diagnostic but there is no

endoscopic hallmark. The endoscopic appearance is

also non-specific. It is difficult to differentiate gastric

MALToma from gastric erosion or gastritis on

conventional white light endoscopy. Diagnosis can

be easily missed if multiple biopsies are not taken.

Narrow-band imaging allows enhanced visualisation

of microvascular and microsurface structures in

the superficial part of the mucosa. The use of ME

with NBI is useful for the diagnosis of early gastric

cancer.7 Recently, retrospective studies have shown

the characteristics of gastric MALToma on ME. Chiu

et al8 reported abnormal spider-like vasculature and

disappearance of gastric pits in nine patients with

histological diagnoses of gastric MALToma, while

Ono et al9 reported that non-structural areas with

abnormal vessels were observed in 11 patients before

treatment. The use of ME may help the endoscopist

to take targeted biopsies from the abnormal areas.10

The histological criteria of gastric MALToma

were established according to the World Health

Organization criteria in 2001, which included

(i) invasion of epithelial structures resulting in

‘lymphoepithelial lesions’; (ii) small lymphocytes,

marginal zone cells, and/or monocytoid B cells; (iii)

infiltration of diffuse, perifollicular, interfollicular, or

even follicular type due to colonisation of reactive

follicles.11

Surgery has been replaced by medical therapy

in the management of gastric MALToma.12 It is

generally recommended that H pylori–eradication

therapy be the first-line therapy for H pylori–positive patients with localised gastric MALToma;

eradication therapy should also be given to H pylori–negative patients, as there may be false-negative results.13 About 60% to 90% of patients with gastric

MALToma achieve complete response after H pylori

eradication.13 The presence of atrophic-like mucosa

is a characteristic finding after treatment of gastric

MALToma. Reported post-treatment ME findings

include recovery of gastric pits and resolution of

abnormal vascular pattern.8 It was demonstrated

that the disappearance of non-structural areas

with abnormal vessels was related to pathological

remission.10

There is no consensus on treatment for those

who fail to respond to eradication therapy. It is

evident that patients with progressive disease or

clinically evident relapse should undergo further

treatment. Different treatment modalities include

chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In a recently

published multicentre cohort, high response rate

to radiotherapy (94%) and chemotherapy (88%)

was reported when used as second-line treatment

in 82 non-responders and eight responders with

relapse.14 Nine patients (out of 420 patients) showed

transformation into diffuse large B cell lymphoma

at a median follow-up period of 6 years.14 The

management of patients with clinically partial

remission is not well defined. A ‘watch and wait’

strategy has been advocated, and patients are

followed up with interval endoscopies for evidence of

progressive disease before considering oncological

treatment.14 Rituximab, a chimeric antibody directed

against CD20, is another therapeutic option. CD20 is

a B cell–specific antigen expressed abundantly by the

neoplastic cells of MALToma. The response rate has

been reported to be around 70% in small series.15

In summary, patients with gastric MALToma

present with non-specific symptoms, and there is no

endoscopic hallmark. Endoscopy and biopsy are the

gold standard for diagnosis. Magnifying endoscopy

findings in MALToma include abnormal vessel

patterns and disappearance of gastric pits; however,

these findings have not been confirmed by large-scale

prospective studies. Helicobacter pylori eradication

is the first-line treatment. While the majority of

patients respond to eradication therapy, those who

fail to respond and develop progressive disease

require oncological treatment. The management

of partial responders is uncertain. Surveillance

endoscopy is recommended in the follow-up of

patients with MALToma in order to detect relapse.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Florence Loong (Department of

Pathology, The University of Hong Kong Li Ka

Shing Faculty of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital) of

providing the histopathology slides.

References

1. Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell

lymphoma. Cancer 1983;52:1410-6. Crossref

2. Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson

PG. Helicobacter pylori–associated gastritis and primary

B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet 1991;338:1175-6. Crossref

3. Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, et al. Regression

of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue type after eradication of

Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 1993;342:575-7. Crossref

4. Zullo A, Hassan C, Cristofari F, et al. Effects of Helicobacter

pylori eradication on early stage gastric mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol

2010;8:105-10. Crossref

5. Stathis A, Chini C, Bertoni F, et al. Long-term outcome

following Helicobacter pylori eradication in a retrospective

study of 105 patients with localized gastric marginal zone

B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Ann Oncol 2009;20:1086-93. Crossref

6. Zullo A, Hassan C, Andriani A, et al. Eradication therapy

for Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastric MALT

lymphoma: a pooled data analysis. Am J Gastroenterol

2009;104:1932-7. Crossref

7. Yao K, Oishi T, Matsui T, Yao T, Iwashita A. Novel

magnified endoscopic findings of microvascular

architecture in intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastrointest

Endosc 2002;56:279-84. Crossref

8. Chiu PW, Wong TC, Teoh AY, et al. Recognition of

changes in microvascular and microstructural patterns

upon magnifying endoscopy predicted the presence of

extranodal gastric MALToma. J Interv Gastroenterol

2012;2:3-7. Crossref

9. Ono S, Kato M, Ono Y, et al. Characteristics of magnified

endoscopic images of gastric extranodal marginal zone

B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid

tissue, including changes after treatment. Gastrointest

Endosc 2008;68:624-31. Crossref

10. Ono S, Kato M, Ono Y, et al. Target biopsy using magnifying

endoscopy in clinical management of gastric mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2011;26:1133-8. Crossref

11. Isaacson PG, Muller-Hermelink HK, Paris MA, et al.

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). In: Jaffe

ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World

Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology

and genetics of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid

tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001: 157-60.

12. Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, et al. The role of surgery in

primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical

trial. Ann Surg 2004;240:44-50. Crossref

13. Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Dragosics B, Greiner

A, Stolte M. Long term outcome of patients with gastric

marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated

lymphoid tissue (MALT) following exclusive Helicobacter

pylori eradication therapy: experience from a large

prospective series. Gut 2004;53:34-7. Crossref

14. Nakamura S, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto T, et al. Long-term

clinical outcome of gastric MALT lymphoma after

eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre cohort

follow-up study of 420 patients in Japan. Gut 2012;61:507-13. Crossref

15. Martinelli G, Laszlo D, Ferreri AJ, et al. Clinical activity

of rituximab in gastric marginal zone non-Hodgkin’s

lymphoma resistant to or not eligible for anti–Helicobacter

pylori therapy. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1979-83. Crossref