DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144259

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Magnetic resonance imaging features of vascular leiomyoma of the ankle

Alta YT Lai, MB, BS, FRCR1;

CW Tam, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

John SF Shum, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)2;

Jennifer LS Khoo, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

WL Tang, FHKCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)3

1 Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2 Radiology Department, Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Clinical Pathology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Alta YT Lai (altalai@gmail.com)

Abstract

Vascular leiomyoma is a benign soft tissue tumour

with a predilection for middle-aged women. It is

most often seen in the extremities, particularly in the

lower leg. The typical lesion is a small, slow-growing

subcutaneous nodule. These tumours are often

unexpected or preoperatively confused with other

soft tissue tumours including low-grade sarcomas,

leading to wide surgical excision. This may partly

be due to the relatively few studies delineating the

characteristic imaging features of this entity. Here,

the imaging findings of a case of vascular leiomyoma

in the ankle are presented. Literature review of the

magnetic resonance imaging findings of published

reports and series of vascular leiomyomas of the

extremities is also performed.

Case report

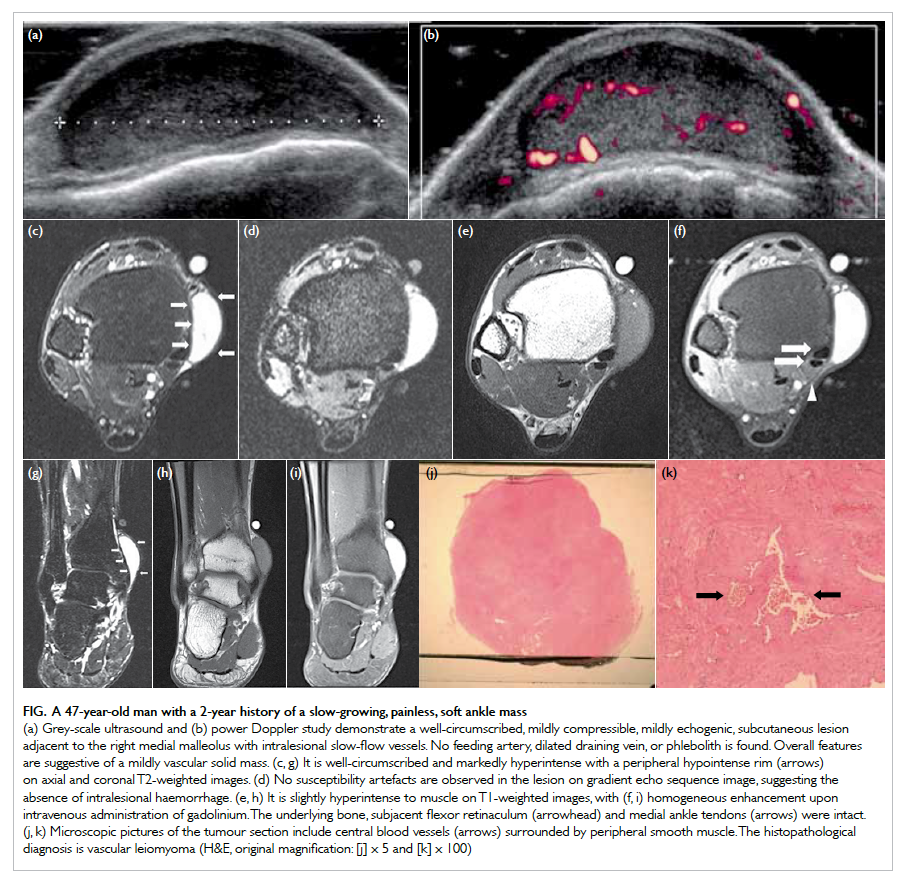

A 47-year-old previously healthy Hong Kong

Chinese man presented in January 2012 with a

2-year history of a slow-growing painless mass over

the right medial malleolus. Physical examination

showed a soft, well-marginated, non-tender mass

measuring 2 cm in diameter over the right medial

malleolus. The patient was referred for ultrasound

and subsequently magnetic resonance imaging (MRI;

Figs a to i). The lesion was excised. Macroscopically,

it was a disc-shaped mass with smooth outer surface.

Cut section showed a mass with a thin capsule and

homogeneous, greyish-to-whitish material without

necrosis. Microscopy showed proliferation of

smooth muscle cells associated with thick-walled

blood vessels without evidence of malignancy. The

histopathological diagnosis was vascular leiomyoma

(Figs j and k).

Figure. A 47-year-old man with a 2-year history of a slow-growing, painless, soft ankle mass

(a) Grey-scale ultrasound and (b) power Doppler study demonstrate a well-circumscribed, mildly compressible, mildly echogenic, subcutaneous lesion adjacent to the right medial malleolus with intralesional slow-flow vessels. No feeding artery, dilated draining vein, or phlebolith is found. Overall features are suggestive of a mildly vascular solid mass. (c, g) It is well-circumscribed and markedly hyperintense with a peripheral hypointense rim (arrows) on axial and coronal T2-weighted images. (d) No susceptibility artefacts are observed in the lesion on gradient echo sequence image, suggesting the absence of intralesional haemorrhage. (e, h) It is slightly hyperintense to muscle on T1-weighted images, with (f, i) homogeneous enhancement upon intravenous administration of gadolinium. The underlying bone, subjacent flexor retinaculum (arrowhead) and medial ankle tendons (arrows) were intact. (j, k) Microscopic pictures of the tumour section include central blood vessels (arrows) surrounded by peripheral smooth muscle. The histopathological diagnosis is vascular leiomyoma (H&E, original magnification: [j] x 5 and [k] x 100)

Discussion

Vascular leiomyoma, angiomyoma or

angioleiomyoma, is a rare benign smooth muscle

tumour that originates in the tunica media of

veins and arteries. It can be located in the skin,

subcutaneous fat, or superficial fasciae of the

extremities. It has a predilection for middle-aged

women. It can occur anywhere in the body, but is

most often seen in the extremities, particularly in

the lower leg.1

The most frequent clinical presentation is a

mass that enlarges slowly over several years. The

size usually ranges from subcentimetre to a few

centimetres in diameter, but occasionally may grow

larger. They are usually oval or round in shape, and

can be located in the skin, subcutaneous fat, or the

superficial fasciae of the extremities.

Pain, with or without tenderness, has been

reported in about 60% of patients, and is thought

to be caused by the active contraction of smooth

muscles resulting in local ischaemia, and is also

suggested to be mediated by intratumoural nerve

fibres.2 Treatment usually consists of marginal

excision.2

Angioleiomyomas are rarely diagnosed

preoperatively. In a series of 10 cases by Gupte et

al1 in 2008, the preoperative or pre-biopsy imaging

diagnoses included sarcoma not otherwise specified,

schwannoma, myositis ossificans, synovial

sarcoma, and fibroma. This may be partly due to the

relatively few studies delineating the characteristic

imaging features of this entity. The preoperative

differentiation of angioleiomyoma from other soft

tissue tumours is of clinical importance, especially

sarcomas, since angioleiomyomas are benign and can

be treated with simple excision. Literature review of

the MRI findings of currently published reports and

series of vascular leiomyomas of the extremities is

presented below.

Literature review

Materials, methods, and patient demographics

A PubMed search of the English literature

was performed, using the key words “vascular

leiomyoma”, “angioleiomyoma”, and “angiomyoma”.

From 1998 to 2011, 36 cases of biopsy-proven

vascular leiomyomas in the extremities of adults

with detailed descriptions of T1-weighted images

(T1WI) and T2-weighted images (T2WI) were

found. Articles without detailed descriptions or

figures of T1WI and T2WI were excluded. Not all

studies in the literature may have been included in

this review because of unavailability in PubMed or

in English language. After including our case, this

review has 37 cases. The mean age of the patients

was 51 years (range, 20-72 years). There were 16 male

and 17 female patients; the gender of the remaining

four patients was not stated.

Results

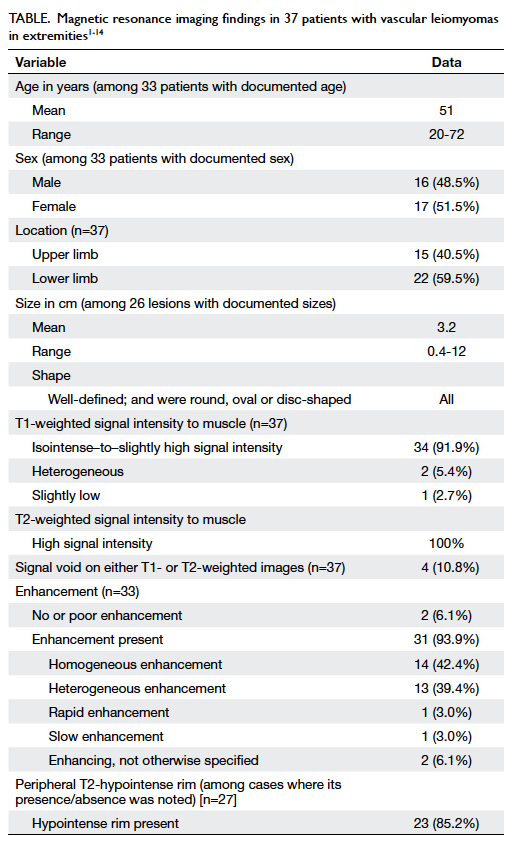

Among the 26 lesions with documented sizes, the

mean size of the lesions was 3.2 cm (range, 0.4-12

cm). Overall, 40.5% (15/37) of the lesions were in the

upper limb and 59.5% (22/37) were in the lower limb.

All of them were located in the subcutaneous layer,

were well-defined, and round, oval or disc-shaped.

On T1WI, 91.9% (34/37) of the tumours showed

isointense–to–slightly high signal intensity, 5.4%

were heterogeneous, and 2.7% showed low signal

intensity. On T2WI, all the cases demonstrated high

signal intensity. Signal voids were seen in 10.8% (4/37)

of the tumours, either on T1WI or T2WI. Among the

33 cases in which contrast was administered, only two

(6.1%) cases showed no or poor enhancement, 93.9%

(31/33) showed enhancement, 42.4% (14/33) were

homogeneous, and 39.4% (13/33) were described

as showing heterogeneous enhancement. One case

showed peripheral enhancement, one showed central

enhancement. One case showed rapid enhancement

and one case demonstrated slow enhancement.

Among the cases in which the presence or absence

of peripheral hypointense rim was recorded, a

hypointense rim was found on T2WI in 85.2% of

cases (23/27; Table1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14).

Table. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in 37 patients with vascular leiomyomas in extremities1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

Vascular leiomyomas often show similar signal

intensity to that of muscle on T1WI. A T2WI is

expected to demonstrate mixed areas that are hyper- and

isointense to muscle. A well-defined peripheral

T2-hypointense rim may be seen, representing

the fibrous capsule. It has been reported that T2-hyperintense areas correlated with strong contrast

enhancement, whereas isointense areas did not show

enhancement after intravenous administration of

contrast material.3 It was suggested that the smooth

muscle and numerous vessels corresponded to the

hyperintense areas, and the fibrous tissue appeared

isointense on T2WI. Tortuous vascular structures

with signal void may also be seen.

Imaging differentials

The differentials of a well-defined, enhancing,

subcutaneous nodule or mass with T2-hyperintense

signals include synovial sarcoma, other low-grade

soft tissue sarcomas, haemangioma, neurogenic

tumour, and nodular fasciitis.

Low-grade sarcomas such as synovial sarcoma

and low-grade myxofibrosarcoma may be slow-growing and appear well-circumscribed on MRI,

giving the misleading impression that the lesion

is well-localised. Haemorrhage may be present in

synovial sarcomas, which may be seen as fluid-fluid

levels, T2 hypointensity, or “triple signal intensity”,

namely areas of hyperintensity, isointensity and

hypointensity relative to fat, due to presence of

cystic, solid and fibrous elements with haemorrhage.

It is unknown whether the absence of haemorrhage,

a more homogeneous appearance, and the presence

of a peripheral hypointense rim are reliable

distinguishing features favouring angioleiomyoma

over otherwise benign-appearing, soft tissue

sarcomas; this may be a potential knowledge gap that

future prospective comparison studies may serve to

fill.

Haemangiomas may show homogeneous

signals if these are small, making it challenging to

differentiate from angioleiomyomas. Phleboliths

can be sought for on plain radiographs. Fatty and

serpentine vascular elements may be identified in

haemangiomas, which are pathognomonic. The

classical ‘target’ sign, ‘split-fat’ sign, and fusiform

tumour shape demonstrated in neurogenic tumours

are not found in angioleiomyomas. Although nodular

fasciitis demonstrates similar shape and size as

angioleiomyomas, linear extension along the fascia,

surrounding oedema, low T1 signal, heterogeneous

T2 signal, and non-homogeneous enhancement

are features that differ from characteristic imaging

features of angioleiomyoma.15

On microscopic examination, the presence

of tortuous vascular channels surrounded by

smooth muscle bundles and areas of myxoid change

may be seen. This explains the heterogeneity of

signal intensity in the tumour on T2WI. Magnetic

resonance imaging–histopathological correlation

published by Hwang et al2 stated that the smooth

muscle and numerous vessels within each type

of vascular leiomyoma corresponded with the

hyperintense areas on T2WI, and the tough fibrous

tissue appeared isointense on T2WI. In addition,

a well-defined peripheral hypointense area on

T2WI correlated with the fibrous capsule, and the

interlacing isointense areas within the tumour

correlated with the various quantity of connective

tissue and intravascular thrombus.3

Conclusions

Vascular leiomyoma should be considered a possible

diagnosis when a well-demarcated oval or round

subcutaneous mass with T1-isointense–to–slightly

high signal, T2-high signal intensity, hypointense

rim, and intense enhancement is seen in the soft

tissue of the extremities. It is unknown whether

the absence of haemorrhage, a more homogeneous

appearance, and the presence of a peripheral

hypointense rim are reliable distinguishing features

favouring angioleiomyoma over otherwise benign-appearing

soft tissue sarcomas; this may be a

potential knowledge gap that future prospective

comparison studies may serve to fill.

References

1. Gupte C, Butt SH, Tirabosco R, Saifuddin A.

Angioleiomyoma: magnetic resonance imaging features in

ten cases. Skeletal Radiol 2008;37:1003-9. CrossRef

2. Hwang JW, Ahn JM, Kang HS, Suh JS, Kim SM, Seo

JW. Vascular leiomyoma of an extremity: MR imaging–pathology

correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;171:981-5. CrossRef

3. Yoo HJ, Choi JA, Chung JH, et al. Angioleiomyoma in soft

tissue of extremities: MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol

2009;192:W291-4. CrossRef

4. Kinoshita T, Ishii K, Abe Y, Naganuma H. Angiomyoma

of the lower extremity: MR findings. Skeletal Radiol

1997;26:443-5. CrossRef

5. Turhan-Haktanir N, Haktanir A, Demir Y, Tokyol C,

Acar M. Toe leiomyoma: A case report with radiological

correlation. Acta Chir Belg 2006;106:92-5.

6. Nagata S, Nishimura H, Uchida M, Hayabuchi N, Zenmyou

M, Fukahori S. Giant angioleiomyoma in extremity: report

of two cases. Magn Reson Med Sci 2006;5:113-8. CrossRef

7. Hamoui M, Largey A, Ali M, et al. Angioleiomyoma in the

ankle mimicking tarsal tunnel syndrome: a case report and

review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg 2010;49:398.e9-15.

8. Shafi M, Hattori Y, Doi K. Angioleiomyoma of distal ulnar

artery of the hand. Hand (N Y) 2010;5:82-5. CrossRef

9. Gulati MS, Kapoor A, Maheshwari J. Angiomyoma of the

knee joint: value of magnetic resonance imaging. Australas

Radiol 1999;43:353-4. CrossRef

10. Kugimoto Y, Asami A, Shigematsu M, Hotokebuchi T.

Giant vascular leiomyoma with extensive calcification in

the forearm. J Orthop Sci 2004;9:310-3. CrossRef

11. Waldt S, Rechl H, Rummeny EJ, Woertler K. Imaging of

benign and malignant soft tissue masses of the foot. Eur

Radiol 2003;13:1125-36.

12. Sookur PA, Saifuddin A. Indeterminate soft-tissue tumors

of the hand and wrist: a review based on a clinical series of

39 cases. Skeletal Radiol 2011;40:977-89. CrossRef

13. Okahashi K, Sugimoto K, Iwai M, Oshima M, Takakura Y.

Intra-articular angioleiomyoma of the knee: a case report.

Knee 2006;13:330-2. CrossRef

14. Stock H, Perino G, Athanasian E, Adler R. Leiomyoma of

the foot: sonographic features with pathologic correlation.

HSS J 2011;7:94-8. CrossRef

15. Walker EA, Fenton ME, Salesky JS, Murphey MD. Magnetic

resonance imaging of benign soft tissue neoplasms in

adults. Radiol Clin North Am 2011;49:1197-217. CrossRef

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: