DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134103

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Xanthogranulomatous inflammation of terminal ileum: report of a case with small bowel

involvement

KC Wong, MCSHK, MRCSEd1;

Wilson MS Tsui, FIAC, FRCPath2;

SJ Chang, FRCS, FRCSEd1

1 Department of Surgery, Caritas Medical Centre, Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Caritas Medical Centre, Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KC Wong(kamkam44@gmail.com)

Abstract

Xanthogranulomatous inflammation is a rare

pathological condition most frequently detected

in the kidney and gallbladder. Reported herein is

a case of xanthogranulomatous inflammation in

a 51-year-old male presenting as a mass-forming

lesion in the terminal ileum with mucosal ulceration.

Diagnostic laparoscopy followed by ileocecectomy

was performed due to intra-operative suspicion

of carcinoma of appendix. This is a report of

the condition involving the terminal ileum with

mucosal ulceration and full-thickness involvement

of bowel wall which are uncommon features of

xanthogranulomatous inflammation in previously

reported lower gastro-intestinal tract lesions.

Introduction

Xanthogranulomatous inflammation (XGI) is a

rare but well-defined disease, first reported by

Oberling in 1935.1 The disease process was most

frequently reported in the kidney and gallbladder.

Rare occurrence in the gastro-intestinal tract was

illustrated in only one recently reported case in the

terminal ileum,2 four reported cases in the colon,3 4 5 6 eight cases in a series of interval appendicectomy

specimens,7 and eight cases with gastric

involvement.8 9 10 11 12 13 Of the four cases with colonic

involvement, two involved the sigmoid colon,3 4 one involved the caecum,5 and one involved the ascending

colon.6 Most of these colonic lesions presented with a

mass-forming lesion with predominant submucosal

involvement, while primary mucosal involvement

was only reported in the last case involving the

ascending colon. We, herein, report the second case

of XGI in the terminal ileum with mucosal ulceration

and full-thickness involvement of the bowel wall,

presenting as a painful right-lower-quadrant

abdominal mass.

Case report

A 51-year-old Chinese male presented to the

Emergency Department on 2 December 2012. He

was a chronic smoker and alcoholic. He complained

of right-sided abdominal pain for the past 2 weeks.

The pain was not associated with nausea, vomiting,

constipation, or diarrhoea. There was no anorexia

or weight loss. There was no history of melaena. His

medical history included diabetes, hypertension,

and gout. There was no history of tuberculosis.

He was admitted to a hospital in Mainland

China 10 days before the index admission for the

same problem. While in that hospital, he had raised

white cell count of 16.2 x 109 /L, and an ultrasound

of abdomen revealed a gallstone and a renal stone.

There was no hydronephrosis. A course of antibiotics

was given, but the symptoms persisted. The patient

returned from Mainland China on 2 December

2012, and attended our Emergency Department for

further management.

On admission, the physical examination of

the respiratory, cardiovascular, and central nervous

systems was unremarkable. Abdominal examination

revealed tenderness in the right lower quadrant.

Per rectal examination revealed no blood, melaena,

or mass. Abdominal X-ray showed no specific

abnormalities.

His blood tests revealed mildly elevated

white cell count of 10.6 x 109 /L (reference range

[RR], 3.7-9.2 x 109 /L), haemoglobin level of 137 g/L

(RR, 134-171 g/L), normal amylase level of 57 U/L

(RR, 30-128 U/L), and normal electrolytes and liver

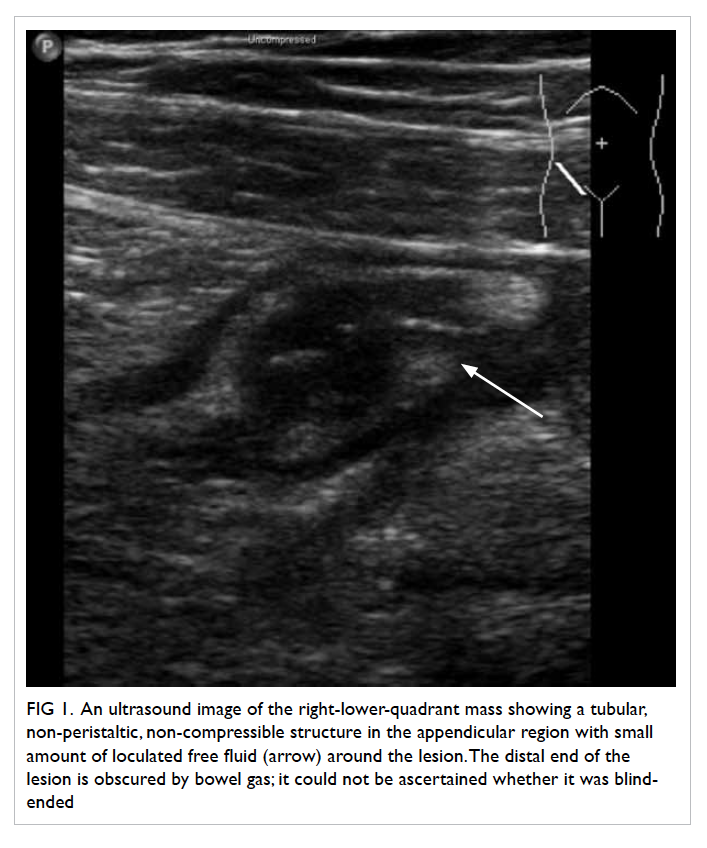

enzymes. An urgent ultrasound of the abdomen

and pelvis raised suspicion of acute appendicitis,

with a tubular, non-peristaltic, non-compressible

structure measuring 1.55 cm in diameter at the

appendicular region, with small amount of loculated

fluid around the lesion (Fig 1), corresponding with

the site of maximum tenderness. The distal end of

the lesion was obscured by bowel gas; it could not be

ascertained whether it was blind-ended. The same

study also revealed the presence of a gallstone and a

right lower pole renal stone.

Figure 1. An ultrasound image of the right-lower-quadrant mass showing a tubular, non-peristaltic, non-compressible structure in the appendicular region with small amount of loculated free fluid (arrow) around the lesion. The distal end of the lesion is obscured by bowel gas; it could not be ascertained whether it was blind-ended

With a preliminary diagnosis of acute

appendicitis, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed

on 3 December 2012. There was an ileocaecal

mass fixed to the posterior abdominal wall, which

was difficult to mobilise despite an open approach

via gridiron incision. Upon conversion to midline

laparotomy, a large inflammatory mass was found

at the ileocaecal junction, compatible with an

infiltrative tumour. The mass demonstrated through-and-through invasion into the ileal mesentery,

involving several loops of the ileum. Ileocaecal

lymph node enlargement was noted. The appendix

was not identified. There was no gross cavity or

pus. With the suspicion of carcinoma of appendix,

limited right hemicolectomy with en-bloc resection

of the mass together with 65 cm of the terminal

ileum, caecum, and proximal ascending colon was

performed. Primary sub-end to sub-end, side-to-side

anastomosis was fashioned.

The postoperative course of the patient was

complicated by on-and-off fever with elevated white

cell count of up to 22.5 x 109 /L. Blood culture taken

on postoperative day 2 yielded no bacterial growth.

Erythema and serous discharge were noted in the

paraumbilical region of the laparotomy and gridiron

wounds, which were managed with dressing and

packing. Wound swab yielded scanty growth of

Escherichia coli. The fever responded to a 10-day

course of cefuroxime and metronidazole. He was

discharged on postoperative day 10.

A colonoscopy done 4 months after the

operation in April 2013 revealed no abnormalities.

Pathological examination

Gross examination of the ileocolectomy specimen

revealed a 0.5-cm ileal mucosal ulcer, which

was 1.5 cm proximal to the ileocaecal valve.

The periappendicular mass was haemorrhagic

and covered with exudate, within which was a

retrocaecal appendix, measuring 5 cm in length

and 1 cm in diameter, surrounded by necrotic and

yellowish tissue. Cut surface of the appendix was

unremarkable. A few lymph nodes were found in the

ileocaecal fossa.

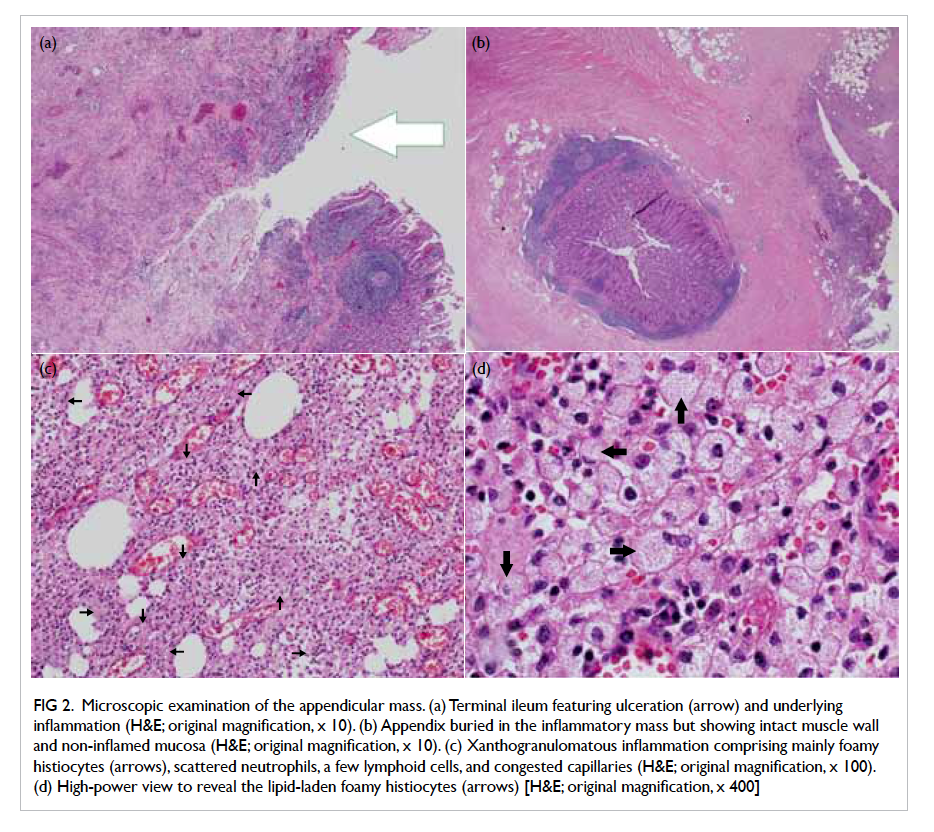

Microscopic examination of the appendicular

mass showed abscess, haemorrhage, and XGI which

consisted predominantly of foamy histiocytes,

scattered neutrophils, lymphoplasmacytic cells,

a few multinucleated giant cells, and congested

capillaries with surrounding fibrosis (Fig 2). The

foamy histiocytes were positive for CD68 on

immunostaining, confirming their histiocytic origin.

No Michaelis-Gutmann bodies were detected. The

terminal ileum ulcer revealed similar XGI which

extended through the bowel wall to involve the

mesentery. The appendicular mucosa showed no

neutrophilic infiltrate. A few reactive lymph nodes

were noted. There was no evidence of malignancy or

granuloma.

Figure 2. Microscopic examination of the appendicular mass. (a) Terminal ileum featuring ulceration (arrow) and underlying inflammation (H&E; original magnification, x 10). (b) Appendix buried in the inflammatory mass but showing intact muscle wall and non-inflamed mucosa (H&E; original magnification, x 10). (c) Xanthogranulomatous inflammation comprising mainly foamy histiocytes (arrows), scattered neutrophils, a few lymphoid cells, and congested capillaries (H&E; original magnification, x 100). (d) High-power view to reveal the lipid-laden foamy histiocytes (arrows) [H&E; original magnification, x 400]

Discussion

Xanthogranulomatous inflammation is a form of

chronic inflammatory condition characterised

macroscopically by mass-forming golden yellow

tumours and microscopically by aggregation of lipid-laden foamy histiocytes including multinucleated

giant cells, with a minor component of chronic and

acute inflammatory cells and fibrous reaction. It was

first described by Oberling in 1935 in three cases of

retroperitoneal xanthogranulomas.1 Its occurrence

in the endometrium, ovary, fallopian tubes, vagina,

testis, epididymis, stomach, bone, skin (as fistulation

secondary to inflammation primarily involving

another internal organ),14 appendix,7 15 urinary

bladder, thyroid, and adrenal glands has been

reported, with the highest prevalence reported in

the kidney and gallbladder. A majority of XGI cases

present as a mass-like lesion with an extension of

fibrosis and inflammation to the surrounding tissues,

leading to diagnostic difficulties in differentiating

them from infiltrative malignant tumours.

Pathological differential diagnoses bearing

similar histological features include malakoplakia,

which is characterised by an inflammatory and

destructive xanthomatous proliferation with the

presence of Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, which are

intracytoplasmic laminated concretions usually

positive for periodic acid–Schiff, von Kossa, and Prussian blue

stains. Macrophages known as von Hansemann

cells are more granular and eosinophilic and have

less vacuolated cytoplasm than ordinary histocytes.

Other differential diagnoses include localised

xanthoma deposits without parenchymal destruction

or xanthomas with prominent foam cell features.

Although the pathological features of XGI are

well described, its exact pathogenesis is not well

established.

Various proposed mechanisms include chronic

recurrent infection, obstruction, immunological

disorders, and defective lipid transport. It is generally

believed that the localised proliferation of lipid-laden

foamy histiocytes in XGI represents chronic

suppurative inflammation secondary to interaction

between the host and micro-organisms. Examples

of immunological disorders include disrupted

chemotaxis of polymorphs and macrophages, which

is a specific immune response toward Proteus and

Escherichia infections. A recently reported case2

involving the terminal ileum proposed a possible

mechanism of perforation due to an ingested foreign

body. However, none of the above hypotheses were

able to fully explain the anatomical distribution of the

condition, which is most common in the appendix

where neither perforation due to ingested foreign

bodies nor chronic suppurative inflammation is

most often found. In this reported case, infected

laparotomy wound swab yielded E coli, while there

were no symptoms to suggest pre-existing chronic

suppurative inflammation. There was no evidence

of a penetrating foreign body on history or gross

examination of the pathological specimen.

Rare occurrence of XGI in the lower gastro-intestinal

tract is illustrated by only one reported

case in the terminal ileum,2 four reported cases in

the colon with two involving the sigmoid colon,3 4 one involving the caecum,5 and one involving the

ascending colon.6 However, a histopathological

review of 22 interval appendicectomy specimens by Guo and Greenson7 in 2003 reported presence of XGI in eight cases (36.4%) of interval appendicectomy

versus none in the 44 matched patients receiving

acute appendicectomy, suggesting XGI may be

underreported as a delayed consequence of acute

inflammation and that these histological changes

are secondary to the time interval of inflammation

rather than intrinsic factors specific to the patient or

disease.

Due to endoscopic, radiological, and the intra-operative

macroscopic resemblance to infiltrative

malignant neoplasms, these lesions warrant excision

with a wide margin, similar to treatment of locally

advanced malignancies.

However, there has been inadequate evidence

to suggest association between XGI and gastro-intestinal

malignancies. Of the eight cases of XGI

of the stomach reported in the literature,8 9 10 11 12 13 co-existence

of XGI with gastric cancer was reported

in three cases. Histological examination of these

cases did not support continuity between the

xanthogranuloma and adenocarcinoma. In the other

case of XGI in the terminal ileum reported by Yoon et

al,2 preoperative endoscopy and biopsy showed ulcers

with acute and chronic inflammation only. However,

surgical resection was considered unavoidable in

view of the radiological findings highly suggestive of

appendiceal cancer. While preoperative endoscopic

biopsy may not be helpful to exclude malignancy as

most of the lesions are submucosal, intra-operative

frozen section may be helpful to avoid unnecessary

radical surgery.

Conclusion

We report a case of XGI with full-thickness

involvement of the terminal ileum presenting with

a tender intraperitoneal mass. This report aimed to

emphasise ileal involvement of XGI, although rare,

as one of the differential diagnoses of mass lesions

in the small bowel mimicking malignant neoplasms.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

References

1. Oberling C. Retroperitoneal xanthogranuloma. Am J

Cancer 1935;23:477-89. CrossRef

2. Yoon JS, Jeon YC, Kim TY, et al. Xanthogranulomatous

inflammation in terminal ileum presenting as an

appendiceal mass: case report and review of the literature.

Clin Endosc 2013;46:193-6. CrossRef

3. Lo CY, Lorentz TG, Poon CS. Xanthogranulomatous

inflammation of the sigmoid colon: a case report. Aust N Z

J Surg 1996;66:643-4. CrossRef

4. Oh YH, Seong SS, Jang KS, et al. Xanthogranulomatous

inflammation presenting as a submucosal mass of the

sigmoid colon. Pathol Int 2005;55:440-4. CrossRef

5. Anadol AZ, Gonul II, Tezel E. Xanthogranulomatous

inflammation of the colon: a rare cause of cecal mass with

bleeding. South Med J 2009;102:196-9.

6. Dhawan S, Jain D, Kalhan SK. Xanthogranulomatous

inflammation of ascending colon with mucosal

involvement: report of a first case. J Crohns Colitis

2011;5:245-8. CrossRef

7. Guo G, Greenson JK. Histopathology of interval (delayed)

appendectomy specimens: strong association with

granulomatous and xanthogranulomatous appendicitis.

Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1147-51. CrossRef

8. Zhang L, Huang X, Li J. Xanthogranuloma of the stomach:

a case report. Eur J Surg Oncol 1992;18:293-5.

9. Guarino M, Reale D, Micoli G, Tricomi P, Cristofori

E. Xanthogranulomatous gastritis: association with

xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. J Clin Pathol

1993;46:88-90. CrossRef

10. Lespi PJ. Gastric xanthogranuloma (inflammatory

malignant fibrohistiocytoma). Case report and literature

review [in Spanish]. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam

1998;28:309-10.

11. Lai HY, Chen JH, Chen CK, et al. Xanthogranulomatous

pseudotumor of stomach induced by perforated peptic

ulcer mimicking a stromal tumor. Eur Radiol 2006;16:2371-2. CrossRef

12. Kubosawa H, Yano K, Oda K, et al. Xanthogranulomatous

gastritis with pseudosarcomatous changes. Pathol Int

2007;57:291-5. CrossRef

13. Kinoshita H, Yamaguchi S, Sakata Y, Arii K, Mori K,

Kodama R. A rare case of xanthogranuloma of the stomach

masquerading as an advanced stage tumor. World J Surg

Oncol 2011;9:67. CrossRef

14. Rogers S, Slater DN, Anderson JA, Parsons MA. Cutaneous

xanthogranulomatous inflammation: a potential indicator

of internal disease. Br J Dermatol 1992;126:290-3.

15. Chuang YF, Cheng TI, Soong TC, Tsou MH.

Xanthogranulomatous appendicitis. J Formos Med Assoc

2005;104:752-4. CrossRef

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: