Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):38–44 | Epub 21 Nov 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144241

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Role of fine-needle aspiration cytology in human immunodeficiency virus–associated lymphadenopathy: a cross-sectional study from northern India

Naveen Kumar, MD1; BB Gupta, MD1; Brijesh Sharma, MD1; Manju Kaushal, MD2; BB Rewari, MD1; Deepak Sundriyal, MD1

1 Department of Medicine, PGIMER and Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi 110001, India

2 Department of Pathology, PGIMER and Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi 110001, India

Corresponding author: Dr Naveen Kumar (docnaveen2605@yahoo.co.in), (2605docnaveen@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the role of fine-needle

aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–associated

lymphadenopathy.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Tertiary care teaching hospital, India.

Patients: Fifty consecutive HIV-positive patients,

who presented with lymphadenopathy at the out-patient

department and antiretroviral therapy clinic.

Results: Tubercular lymphadenitis was the most

common diagnosis, reported in 74% (n=37) of

patients; 97.2% of them were acid-fast bacilli–positive. Reactive lymphadenitis and fungal

lymphadenitis were present in 10 and 1 cases,

respectively. The most common cytomorphological

pattern of tubercular lymphadenitis was necrotising suppurative

lymphadenitis, present in 43.2% (n=16)

of patients. Of eight biopsies done in reactive cases,

six turned out to be tubercular lymphadenitis. Fine-needle

aspiration cytology had a sensitivity of 83.7%

for diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis.

Conclusion: Necrotising suppurative lymphadenitis

should be recognised as an established pattern of

tubercular lymphadenitis. Reactive patterns should

be considered inconclusive rather than a negative

result, and re-evaluated with lymph node biopsy.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology is an excellent test

for diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis in HIV-associated

lymphadenopathy.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Necrotising suppurative lymphadenitis should be recognised as an established pattern of tubercular lymphadenitis.

- In advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, reactive lymphadenitis should be considered inconclusive rather than a negative result, and re-evaluated with lymph node biopsy.

- As lymphadenopathy is common in all stages of HIV disease, judicious use of fine-needle aspiration cytology can be helpful in diagnosing associated opportunistic infections and other pathological conditions.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

is an important worldwide public health problem.

Developing nations, where resources are limited, are

the worst affected nations. Until curative treatment

for HIV infection becomes available, the crux of

management is early diagnosis and treatment with

highly active antiretroviral therapy.

As HIV is a lymphotropic virus, lymphoid

tissues are the major anatomical site where the

virus establishes itself during early infection. These

lymphoid tissues act as reservoirs for the virus in

the asymptomatic phase of infection. In the late

stage, HIV disseminates from these sites to cause a

full-blown acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

(AIDS).1 Thus, lymph node involvement is found

in all stages of infection. The cause of lymph node

enlargement is often difficult to establish by history,

physical examination, radiographic studies, and

routine laboratory tests. Surgical biopsy is the gold

standard for diagnosis. However, it has several

drawbacks: costly, time-consuming, and requiring

more elaborate precautions. Fine-needle aspiration

cytology (FNAC) does not have any of these

limitations, and is also comparatively less invasive.

Furthermore, the cost of aspiration cytology is only

10% to 30% of that of surgical biopsy.2

We performed FNAC to establish the

aetiological diagnosis in our study subjects with HIV

infection. To detect false-negative results, biopsy was

done in cases diagnosed as reactive lymphadenitis.

The aims of the study were to assess the accuracy of

FNAC and to correlate the findings with clinical and

laboratory parameters like CD4 counts.

Methods

The study was conducted in the Departments of

Medicine and Pathology, PGIMER and Dr RML

Hospital, New Delhi, India, from January 2009 to

December 2009. The study protocol and proforma

were approved by the ethics committee of the

institute. Informed written consent was obtained

from all patients. Fine-needle aspiration cytology

was performed in 50 consecutive HIV-positive

patients presenting with lymphadenopathy at the

antiretroviral clinic, or the out-patient or in-patient

services. Detailed history was taken and examination

of the patients was performed. Clinical stage (as per

the World Health Organization [WHO] classification)

and CD4 counts were recorded for all patients. Fine-needle

aspiration cytology was performed by the

clinician on the largest non-inguinal lymph node

using standard precautions. The area was cleaned

and draped. A 10-mL syringe and 23-gauge needles

were used. If the sample was insufficient, another

sample was taken from a different lymph node. Slides

for Papanicolaou and Periodic-acid Schiff (PAS)

stains were fixed with 95% ethanol immediately after

preparing the smear; others were air dried. A total of

six slides were prepared from each aspirate and were

immediately processed by staining with Giemsa

stain, Papanicolaou’s stain, Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain

for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), PAS stain for fungi, and

Gram stain. Cases that were AFB-positive on ZN

staining were diagnosed as tubercular lymphadenitis;

otherwise, they were retained as suspected cases.

Based on the presence or absence of granulomas,

caseation (necrosis) and neutrophilic infiltration,

tubercular lymph nodes were classified into four

cytomorphological categories: granulomatous

lymphadenitis (GL), necrotising granulomatous

lymphadenitis (NGL), necrotising lymphadenitis

(NL), and necrotising suppurative lymphadenitis

(NSL). Lymph node biopsies were performed in

cases which showed a reactive pattern or suspected

tubercular lymphadenitis on FNAC. Sensitivity,

specificity, and positive and negative predictive

values were calculated for FNAC as a diagnostic

modality compared with biopsy. Statistical analysis

for association between FNAC findings and

various parameters was done using univariate

and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Data

analysis was performed by the Statistical Package for the

Social Sciences (Windows version 19.0; SPSS Inc,

Chicago [IL], US). A P value of less than 0.05 was

regarded as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 50 patients (43 men and 7 women) were

included in the study. The mean age of the patients

was 32.4 years. Cervical region was the most

common site of lymphadenopathy (n=39; 78%)

followed by axillary and inguinal regions. The lymph

nodes were matted and generalised in 62% (n=31)

and 48% (n=24) of cases, respectively. Generalised

lymphadenopathy was present in 54% (n=20) of

cases with tubercular lymphadenitis and 40% (n=4)

of cases with reactive lymphadenitis. Nature of

aspirate was bloody in 21 (42%) cases, caseous in 24

(48%), and mixed (with blood and caseation) in the

remaining patients. The CD4 count ranged from

12 cells/µL to 353 cells/µL, with a mean count of 131

cells/µL. Most of the patients were in WHO clinical

stage 3 (n=31; 62%).

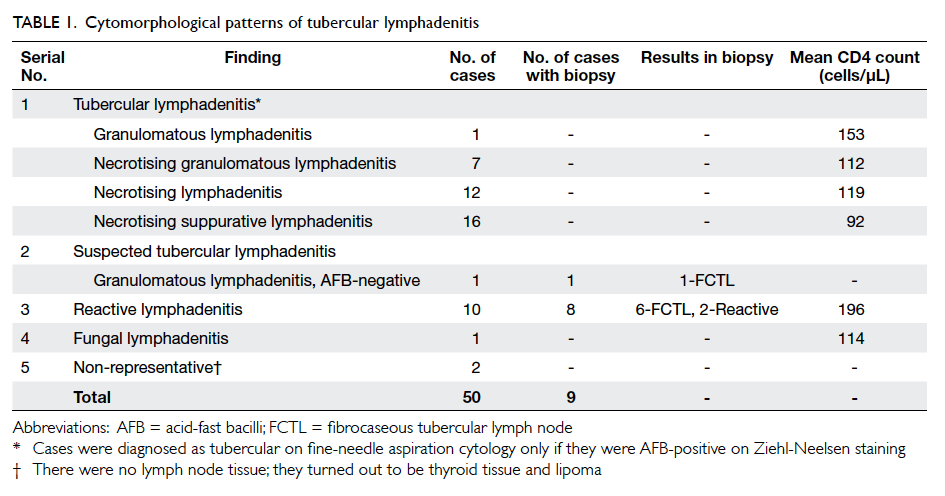

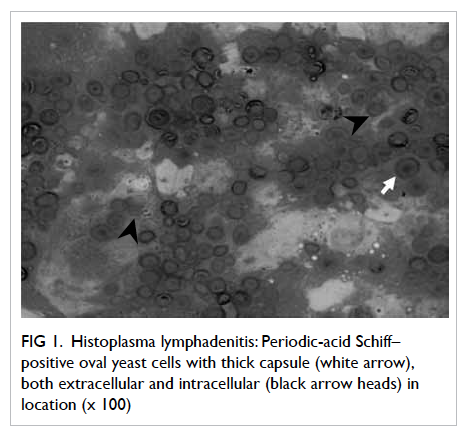

The most common cytological diagnosis was

tubercular lymphadenitis (n=37; 74%) followed by

reactive pattern (n=10; 20%). Only one FNAC was

diagnosed as fungal lymphadenitis showing PAS-positive

spores of Histoplasma capsulatum (Fig 1). In two cases, the cytologies were suggestive of thyroid tissue and lipoma; these were treated as failed FNACs. Tubercular lymphadenitis was further categorised into four cytomorphological patterns, as shown in Table 1. All tubercular cases were AFB-positive except one which was a AFB-negative GL on FNAC. Subsequently, this was shown to be AFB-positive tubercular lymphadenitis on biopsy. Of the 10 cases reported as reactive lymph nodes on FNAC, eight gave consent for biopsy. Biopsy showed AFB-positive fibrocaseous tubercular lymphadenopathy in six out of these eight cases; in the remaining

two cases, biopsy findings matched with the FNAC findings.

Figure 1. Histoplasma lymphadenitis: Periodic-acid Schiff–positive oval yeast cells with thick capsule (white arrow), both extracellular and intracellular (black arrow heads) in location (x 100)

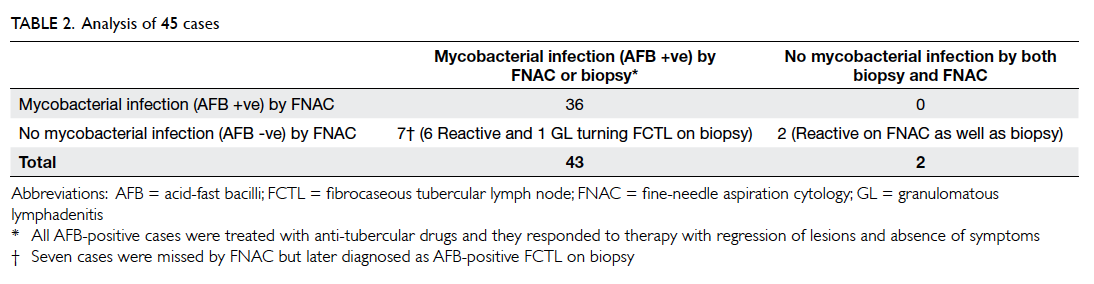

All cases diagnosed as having mycobacterial

disease on FNAC and those who underwent biopsy

were included in the analysis. Hence 45 cases were

analysed: 36 cases diagnosed as mycobacterial

(tubercular) lymphadenitis on FNAC, one case of

GL which was AFB-positive fibrocaseous tubercular

lymph node on biopsy, and eight cases of reactive

lymphadenopathy that underwent biopsy (Table 2). The sensitivity and negative predictive value of

FNAC for diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis were

83.7% and 22.2%, respectively. As AFB positivity was the requisite criterion for diagnosing

tubercular lymphadenitis, it was expected that there

would be no diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) in any

case which was AFB-negative on FNAC; thus, the

specificity and positive predictive value were 100%.

We performed logistic regression analysis with

tubercular lymphadenitis as the dependent variable

and four parameters as covariates. On univariate

analysis, CD4 count (P=0.016), nature of aspirate

(P=0.013), and matted nodes on examination

(P=0.028) were associated with tubercular aetiology

on FNAC; lymph node distribution did not show any

such association (P=0.401). However, in multivariate

analysis, none of these factor was associated with

tubercular aetiology on FNAC. Moreover, none of

these factors was associated with the severe form

(NL or NSL) of tubercular lymphadenitis either on

univariate or multivariate analysis.

Discussion

Lymphadenopathy in HIV patients is very

common; it can be a presenting feature in about

35% of patients with AIDS.3 Causes can be varied,

depending on the stage of the disease, and may

include persistent generalised lymphadenopathy,

lymphoid malignancies, and opportunistic infection.

All these can be easily and efficiently diagnosed

by aspiration study of these lymph nodes. These

causes of lymphadenopathies are important causes

of death in AIDS patients. In this study, we aimed

to investigate the performance of FNAC for the

accurate diagnosis of lymphadenopathies. We also

compared our results with those from similar Indian

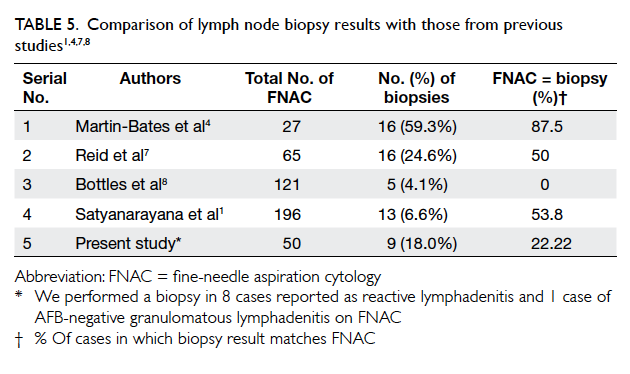

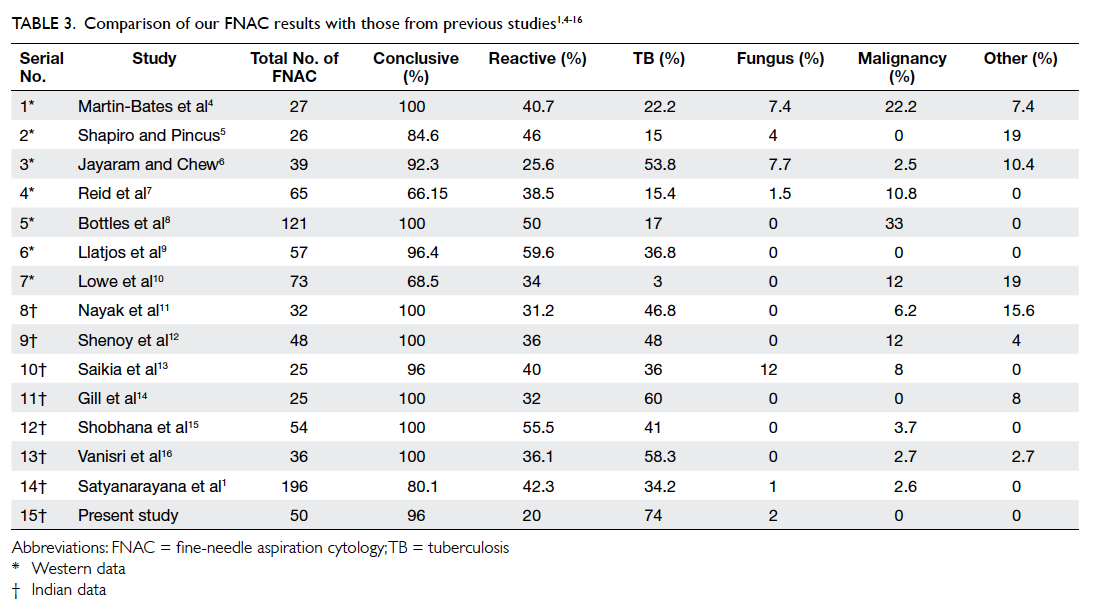

and western studies (Table 3

1 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16).

Table 3. Comparison of our FNAC results with those from previous studies1 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Tuberculosis is the most frequent opportunistic infection in HIV patients.17 18 Lymph nodes are the commonest site of extra-pulmonary TB in patients with AIDS.19 20 Using FNAC as the diagnostic modality, we also found tubercular lymphadenitis to be the most common cause of lymphadenopathy, present in 74% of our patients. Similar conclusion was drawn in other Indian studies; however they reported a prevalence of 34.2% to 60% (Table 3). The high prevalence of tubercular lymphadenitis in our series may be related to the low immunity of the majority of patients; 41 out of 50 patients had CD4 counts of <200 cells/µL.

There are two specific pathological criteria for

diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis—caseation

and granuloma formation. Both are less likely to

be present in tubercular lymphadenitis associated

with advanced HIV disease. This is because T-cell

function, which is suppressed in advanced HIV

disease, is required for granuloma formation. On the

basis of these two findings, tubercular lymphadenitis

is classified into three categories21 22: GL, NGL, and

NL.

The GL pattern can occur due to several

causes. However, in a country like India, where TB

is very common, this pattern is considered to be

due to TB until proven otherwise. We found this

pattern in 5.4% (2 out of 37 cases with tubercular

lymphadenitis) of TB cases, a finding similar to that

in other previous studies where it ranged from 4.3%

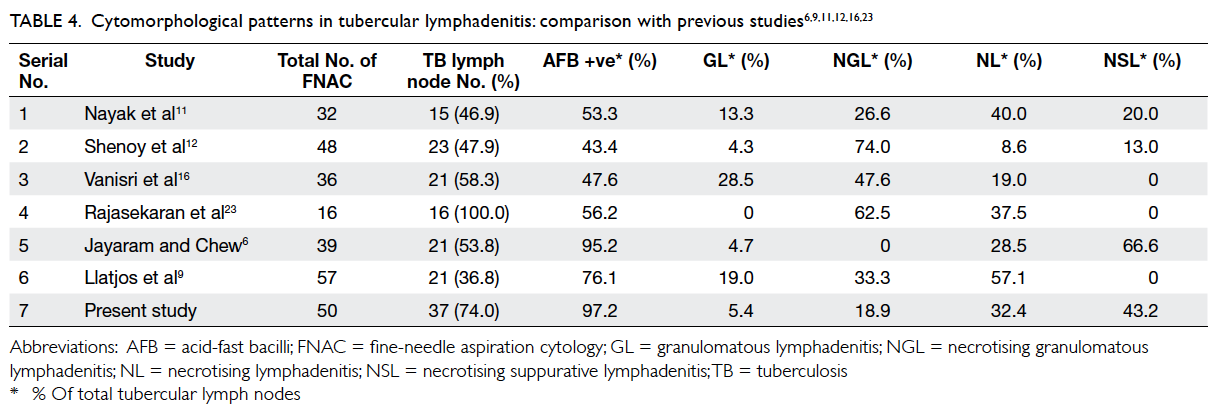

to 28.5% (Table 4).6 9 11 12 16 23 The NGL pattern, with

both caseation and epithelioid granulomas, is the

most typical pattern of tubercular lymphadenitis. It

was present in 18.9% (7 out 37 cases of tubercular

lymphadenitis) of our cases; other studies have

reported it in the range of 26.6% to 74% (Table 4).9 11 12 16 23 Necrotising lymphadenitis represents

the most severe cytomorphological pattern of tubercular lymphadenitis. There is complete

necrosis with only ‘acellular’ debris. It is not labelled as ‘purulent’ because there are no degenerated

polymorphonuclear cells. Complete necrosis reflects impaired cell-mediated immunity in this group of

patients. Cases of NGL can be wrongly labelled as NL if material is aspirated from that part of the node

which contains only caseation. This was the second most common pattern reported in our study (32.4%;

12 out of 37 cases of tubercular lymphadenitis). In other studies, the reported prevalence rates range

from 8.6% to 57.1% (Table 4).6 9 11 12 16 23

Table 4. Cytomorphological patterns in tubercular lymphadenitis: comparison with previous studies6 9 11 12 16 23

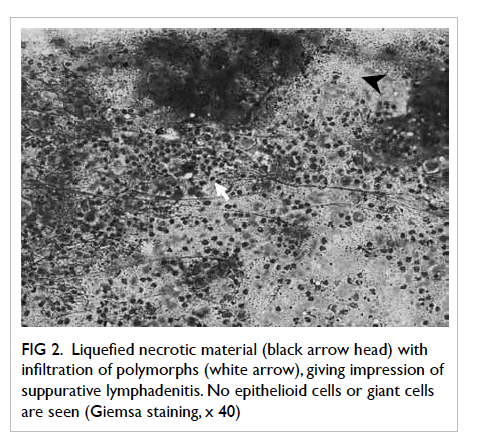

The NSL pattern of tubercular lymphadenitis

(Fig 2) was the most common cytomorphological

picture, seen in 43.2% (16 out of 37 cases of tubercular lymphadenitis) of patients. This pattern

was reported in 20% and 13% cases of tubercular lymphadenitis by Nayak et al11 and Shenoy et al,12 respectively (Table 4). Jayaram and Chew6 reported this pattern in 67% of their TB cases in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Although reported in these case series, unlike the other three patterns, the NSL pattern is not yet a well-recognised cytomorphological type of tubercular lymphadenitis. However, this pattern is important, especially in HIV patients. If ZN staining is not done, the thin caseation commonly present in these cases can be mistaken for pus, and the case wrongly labelled as pyogenic lymphadenitis. Similar observations have been made in some studies.6 11 12 24

Figure 2. Liquefied necrotic material (black arrow head) with infiltration of polymorphs (white arrow), giving impression of suppurative lymphadenitis. No epithelioid cells or giant cells are seen (Giemsa staining, x 40)

Studies have shown that FNAC is more sensitive for the diagnosis of TB in HIV-positive patients than in seronegative patients.25 In our series, AFB positivity rate in TB cases was 97.2% (n=36/37),

which was higher than that in previous studies (43.4% to 95.2%).6 9 11 12 16 This could be due to the fact that the disease was quite advanced in our group of tubercular lymphadenitis patients (mean CD4 count of 108 cells/µL). Moreover, as the cytomorphological pattern deteriorated and necrosis appeared, AFB positivity increased from 50% to 100%. This was in agreement with data from earlier studies.6 9 11 12 16 Chances of detecting AFB were least in lymph nodes

showing GL pattern: four out of five studies6 9 11 12 16 did not report any AFB-positive case with this pattern of lymphadenopathy. Further, although TB is very common in HIV subjects, Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is not frequently seen in India. Its chance further decreases by adding MAC prophylaxis of azithromycin to the patient’s treatment regimen.

A reactive lymphadenitis was observed in only 20% of cases in our study. Most of the western studies reported it as the most common lymph node pathology, observed in 25.6% to 59.6% of cases (Table 3). One case of histoplasmosis was detected in our

study (Fig 1). On Giemsa staining, the lymph

node showed reactive lymphoid cells, histiocytes, areas of granuloma formation, along with sheets

of Histoplasma capsulatum organism, located both extracellularly and intracellularly, which were

positive on PAS staining. Hence, although the finding of GL without AFB in HIV-infected patients

in India is taken as TB unless proven otherwise, causes like fungal infection (by PAS staining) should

be excluded, especially if the CD4 count is low.

We performed a lymph node biopsy in 18% of our cases (Table 5). Among these, the findings

were different from those in FNAC in 77.8% of the cases. False-negative rate in our study was 16.3% (7

out of 43 cases of TB; Table 2). The false-negative rate in other studies ranges from 2% to 9.2%.1 4 7 8 Of these seven false-negative cases, six were diagnosed

as reactive nodes on FNAC which later showed fibrocaseous nodes on biopsy. Possible reasons for

discordance could be focal tubercular involvement of the nodes. On FNAC, the tubercular area could

have been missed and, hence, wrongly labelled as reactive cases. Also, different nodes in the same area can enlarge due to different pathologies. Hence, a report of reactive pattern in advanced disease, like in our group of patients (mean CD4 in reactive group being 196 cells/µL), does not have much value, and should not be the end of further assessment. It should be considered an inconclusive result rather

than a negative one. It emphasises the importance of performing a biopsy in this group of patients.

A falling CD4 count in our group of patients

was associated with increasing risk of tubercular

lymphadenitis. However, CD4 counts did not

predict the severity of cytomorphological forms

of tubercular lymphadenitis. Of note, 41 out of 50

patients had CD4 counts of <200 cells/µL. Hence,

we did not have a group of patients with higher

CD4 counts in whom less severe forms of tubercular

lymphadenitis were more common. This association

should be studied further by recruiting patients with

a wide range of CD4 counts.

In univariate analysis, a matted lymph node

on examination (P=0.028) and caseous material

(P=0.013) on aspiration were found more often in TB

cases versus reactive cases. Hence, apart from routine

cytology stains, these observations guide us for

ordering special staining like ZN staining. However,

their association with cytomorphological pattern

of TB was not significant on univariate analysis, as

the whole spectrum of pattern can have caseation

on aspiration (except GL) and matted nodes on

examination, although cytomorphologically these

are of increasing severity.

Conclusion

Tuberculosis is the most common aetiology of

HIV-associated lymphadenopathy in India. Acid-fast

bacilli positivity is very high in HIV-associated

tubercular lymphadenitis. We recommend routine

AFB staining for all lymph nodes undergoing FNAC

in HIV patients. Lymph nodes showing AFB-negative

GL pattern on FNAC should be stained for

fungus, especially if CD4 count is low. If a patient’s

CD4 count is low, a reactive FNAC pattern should be

taken as an inconclusive result and is an indication

for biopsy. All lymph nodes showing NSL pattern on

FNAC should undergo ZN staining in HIV-positive

patients. It should be recognised as a tubercular

cytomorphological pattern, especially in patients

with low immunity like those with AIDS. Fine-needle

aspiration cytology of lymph nodes is a valuable test

for diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis in HIV-associated

lymphadenopathy.

References

1. Satyanarayana S, Kalighatgi AT, Murlidhar A, Prasad RS,

Jawed KZ, Trehan A. Fine needle aspiration cytology of

lymph node in HIV infected patients. Medical Journal

Armed Forces India 2002;58:33-7. CrossRef

2. Kaminsky DB. Aspiration biopsy for community hospital.

In: Johnston WW, editor. Masson monograph in

diagnostic cytopathology. New York: Masson Publication; 1981: 12-3.

3. Guidelines for prevention and management of common

opportunistic infection/malignancy among HIV-infected

adult and adolescents. NACO. Ministry of Health & Family

Welfare. Government of India; May 2007.

4. Martin-Bates E, Tanner A, Suvarna SK, Glazer G, Coleman

DV. Use of fine needle aspiration cytology for investigating

lymphadenopathy in HIV positive patients. J Clin Pathol

1993;46:564-6. CrossRef

5. Shapiro AL, Pincus RL. Fine-needle aspiration of diffuse

cervical lymphadenopathy in patients with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg 1991;105:419-21.

6. Jayaram G, Chew MT. Fine needle aspiration cytology

of lymph nodes in HIV-infected individuals. Acta Cytol

2000;44:960-6. CrossRef

7. Reid AJ, Miller RF, Kocjan GI. Diagnostic utility of fine

needle aspiration (FNA) cytology in HIV-infected patients

with lymphadenopathy. Cytopathology 1998;9:230-9. CrossRef

8. Bottles K, McPhaul LW, Volberding P. Fine-needle aspiration

biopsy of patients with acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome (AIDS): experience in an outpatient clinic. Ann

Intern Med 1988;108:42-5. CrossRef

9. Llatjos M, Romeu J, Clotet B, et al. A distinctive cytologic

pattern for diagnosing tuberculous lymphadenitis in AIDS.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993;6:1335-8.

10. Lowe SM, Kocjan GI, Edwards SG, Miller RF. Diagnostic

yield of fine-needle aspiration cytology in HIV-infected

patients with lymphadenopathy in the era of highly active

antiretroviral therapy. Int J STD AIDS 2008;19:553-6. CrossRef

11. Nayak S, Mani R, Kavatkar AN, Puranik SC, Holla VV.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology in lymphadenopathy of

HIV-positive patients. Diagn Cytopathol 2003;29:146-8. CrossRef

12. Shenoy R, Kapadi SN, Pai KP, et al. Fine needle aspiration

diagnosis in HIV related lymphadenopathy in Mangalore,

India. Acta Cytol 2002;46:35-9. CrossRef

13. Saikia UN, Dey P, Jindal B, Saikia B. Fine needle aspiration

cytology in lymphadenopathy of HIV-positive cases. Acta

Cytol 2001;45:589-92. CrossRef

14. Gill PS, Arora DR, Arora B, et al. Lymphadenopathy.

An important guiding tool for detecting hidden HIV-positive cases: a 6-year study. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS

Care (Chic) 2007;6:269-72. CrossRef

15. Shobhana A, Guha SK, Mitra K, Dasgupta A, Neogi DK,

Hazra SC. People living with HIV infection / AIDS—a study on lymph node FNAC and CD4 count. Indian J Med Microbiol 2002;20:99-101.

16. Vanisri HR, Nandini NM, Sunila R. Fine-needle aspiration

cytology findings in human immunodeficiency virus

lymphadenopathy. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2008;51:481-4. CrossRef

17. Harries AD. Tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency

virus infection in developing countries. Lancet

1990;335:387-90. CrossRef

18. Sharma SK, Kadhiravan T, Banga A, Goyal T, Bhatia I,

Saha PK. Spectrum of clinical disease in a series of 135

hospitalised HIV-infected patients from north India. BMC

Infect Dis 2004;4:52. CrossRef

19. Shafer RW, Kim DS, Weiss JP, Quale JM. Extrapulmonary

tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency

virus infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991;70:384-97. CrossRef

20. Arora VK, Kumar SV. Pattern of opportunistic pulmonary

infections in HIV sero-positive subjects: observations

from Pondicherry, India. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci

1999;41:135-44.

21. Das DK, Pant JN, Chachra KL, et al. Tuberculous

lymphadenitis: correlation of cellular components and

necrosis in lymph-node aspirate with A.F.B. positivity and

bacillary count. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 1990;33:1-10.

22. Das DK. Fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of

tuberculous lesion. Lab Med 2000;31:625-32. CrossRef

23. Rajasekaran S, Gunasekaran M, Jayakumar DD, et al.

Tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis in HIV positive and

negative patients. Indian J Tuberc 2001;48:201-4.

24. Havlir DV, Barnes PF. Tuberculosis in patients with

human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med

1999;340:367-73. CrossRef

25. Shriner KA, Mathisen GE, Goetz MB. Comparison of

mycobacterial lymphadenitis among persons infected with

human immunodeficiency virus and seronegative controls.

Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:601-5. CrossRef

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: