Hong Kong Med J 2014;20(6):511–8 | Epub 29 Aug 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134150

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Nurse-led orthopaedic clinic in total joint replacement

Jason CH Fan, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); Carmen KM Lo, MN; Carson KB Kwok, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); KY Fung, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong

This study was presented at the 33rd Annual Congress of the Hong Kong

Orthopaedic Association on 23 November 2013.

Corresponding author: Dr Jason CH Fan (fchjason@netvigator.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To introduce the practice of a nurse-led

orthopaedic clinic for managing stable patients

after total hip or knee replacement and to evaluate

its efficacy.

Design: Case series.

Setting: A public hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: Patients who had stable primary total knee

replacement or total hip replacement done for longer

than 2 years were managed in a nurse-led total joint

replacement pilot clinic.

Results: From July 2012 to March 2014, 431 patients

(including 317 with total knee replacement and

114 with total hip replacement) were handled, and

408 (94.7%) nurse assessments were independently

performed. Six cases of prosthesis-related

complications were diagnosed. One patient was

hospitalised for prosthetic complications within

3 months after follow-up. The satisfaction rate

was 100%. From November 2012 to April 2013, an

advanced practice nurse, one resident specialist,

and one associate consultant independently charted

Knee Society Knee Score or Harris Hip Score for the

patients attending preoperative assessment clinic

to check the inter-observer reliability. Overall, 23

patients with 37 knees and 11 patients with 17 hips

were examined. The mean correlation coefficient

between assessments by the associate consultant

and advanced practice nurse was 0.912 for Knee

Society Knee Score, and 0.761 for Harris Hip Score.

The advanced practice nurse could achieve better

or equally good correlation with associate consultant when compared with the correlation between resident specialist and associate consultant (0.866 and 0.521 for Knee Society Knee Score and Harris Hip Score, respectively) and with international standard.

Conclusion: Nurse-led total joint replacement clinic

was safe, reliable, and well accepted by patients.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Management of stable postoperative total joint replacement patients by well-trained nurses is safe, reliable, and well accepted by patients.

- Nurse-led clinics should be established for managing patients with total joint replacement to handle the escalating workload in Hong Kong.

- Well-structured nurse training should be organised for managing stable patients with total joint replacement in orthopaedic clinics.

Introduction

Nursing practice is moving towards both

proletarianisation and professionalisation.1 The

former means the transfer of some basic routine care

to less-skilled assistants. The latter means advanced

nursing practice with nurses handling complex

health problems using advanced health assessment

and intervention measures. Nurse-led clinic is one

of the forms of professionalisation and has been

adopted in Hong Kong since 1990s. Diabetes clinic,

wound clinic, and continence clinic are the three

most common nurse-led clinics in Hong Kong2

and they have demonstrated significant impact on

patient outcomes.3 Orthopaedic nurses in total joint

replacement (TJR) have been focusing on patient

education in preoperative assessment clinics.

In order to enhance the role of orthopaedic

nurses and ensure the continuity of patient care

before and after TJR, a new advanced nursing

practice was introduced, namely, the Ambulatory

Comprehensive Arthroplasty Clinic (ACAC), a

nurse-led orthopaedic postoperative clinic in TJR.

An advanced practice nurse (APN) with 17 years of

post-registration experience and 5 years of advanced

nursing practice was interviewed and showed

dedication and enthusiasm towards the orthopaedic

work in TJR. She received some basic training from

November 2011 and the ACAC started in January

2012. She ran the clinic one session each week

under the supervision of an associate consultant

(AC) till June 2012, and then independently. She

was supported by a multidisciplinary team and

could refer patients to physiotherapy, occupational

therapy, and prosthetics and orthotics as indicated.

She also participated in a multidisciplinary meeting

for day-patient rehabilitation after TJR.

The APN continued with her one-on-one

training by an AC specialised in TJR. Each week,

she observed about 15 cases in the specialist TJR

clinic and two cases in the preoperative assessment

clinic. She was exposed to and was taught the basic

knowledge on total knee replacement (TKR) and

total hip replacement (THR), the proper way to

chart Knee Society Knee Score (KSKS) and Harris

Hip Score (HHS), and about physical findings

and radiographic features of stable prosthesis,

infection, and aseptic loosening. Reading material

and tutorials were also provided to teach her about

various complications of TJR. Until March 2014, she

completed about 110 weeks of continuous training.

As we have been using KSKS and HHS since

1998 for assessing the progress of patients after TJR,

these were retained as part of the assessment tools

in ACAC for continuity of care. In part of the KSKS

and HHS, physical examination is necessary. It was a

difficult area for the APN and could lead to potential

error and discrepancy. Therefore, part of the APN

training was concentrated in this area and a separate

study was launched to test her reliability.

This article aimed to introduce the practice of

a nurse-led orthopaedic clinic for managing stable

postoperative patients with TKR and THR and

describe the outcomes in a series of cases. This also

presents the result of the reliability of the APN in

charting various scores.

Methods

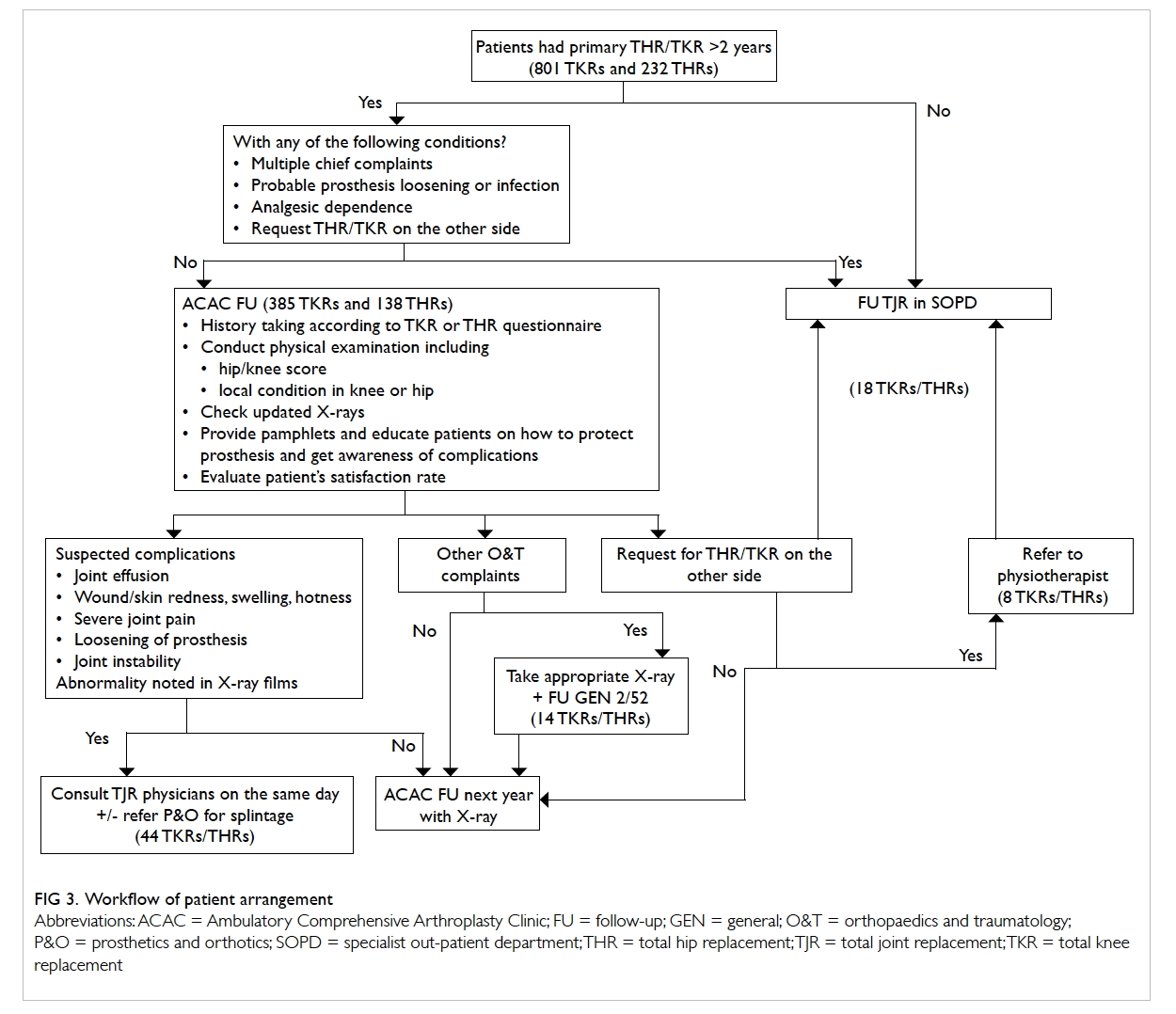

From August 1997 to December 2013, 895 primary

TKRs and 268 primary THRs were performed in

Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital. Until 31

December 2013, 801 TKRs and 232 THRs were

performed for more than 2 years and were followed

up yearly in the specialist out-patient clinic. During

each follow-up, the assessment included history

taking and physical examination, charting KSKS

or HHS, and checking radiographs. Patients who

had undergone primary TKR or THR more than 2

years ago and who were assessed as being stable and

minimally symptomatic by specialists were recruited

in the ACAC for yearly follow-up. One day before

follow-up, the AC analysed the radiographs taken in

the earlier year and the finding was discussed with

the APN for teaching purpose. During ACAC, the

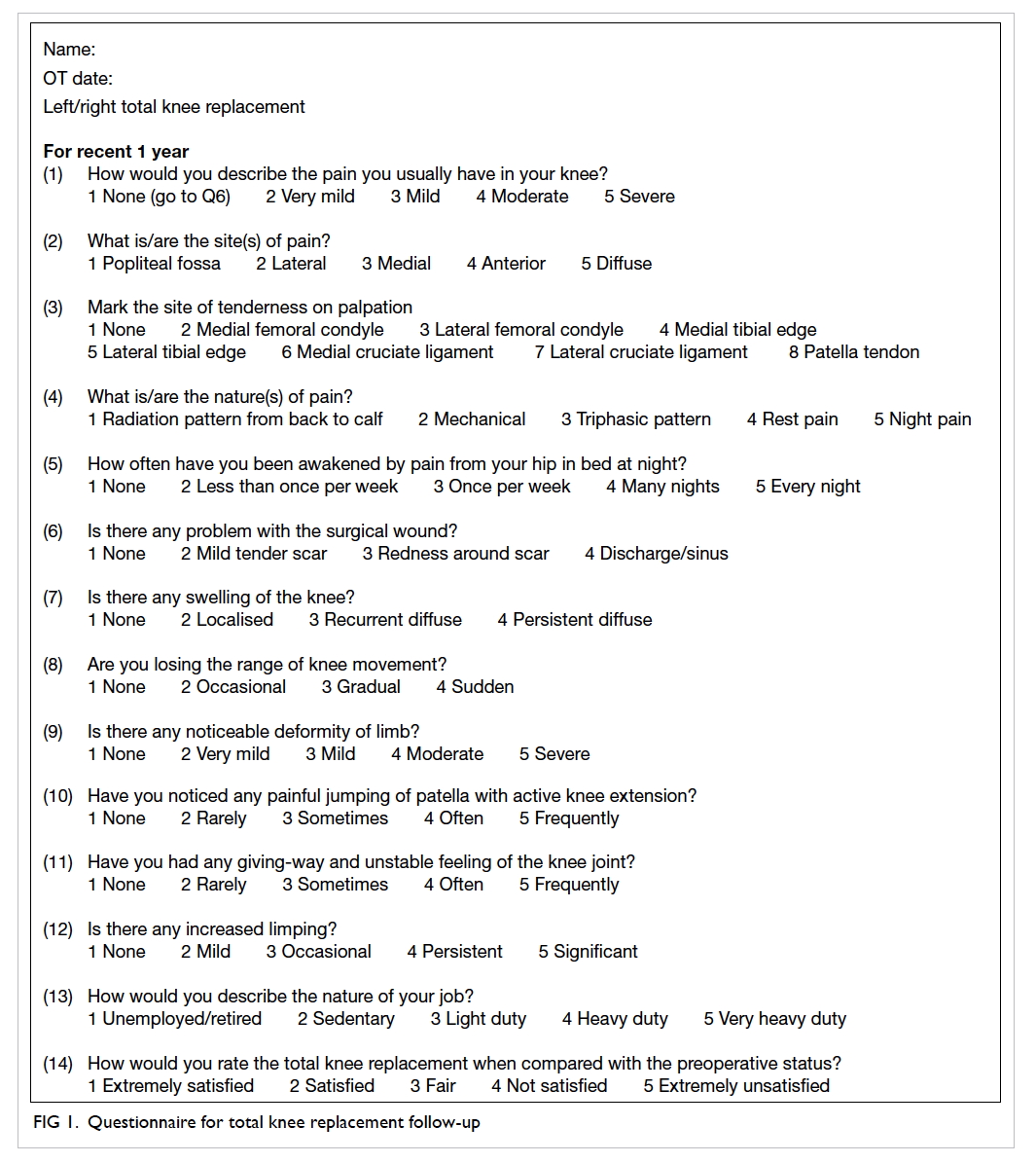

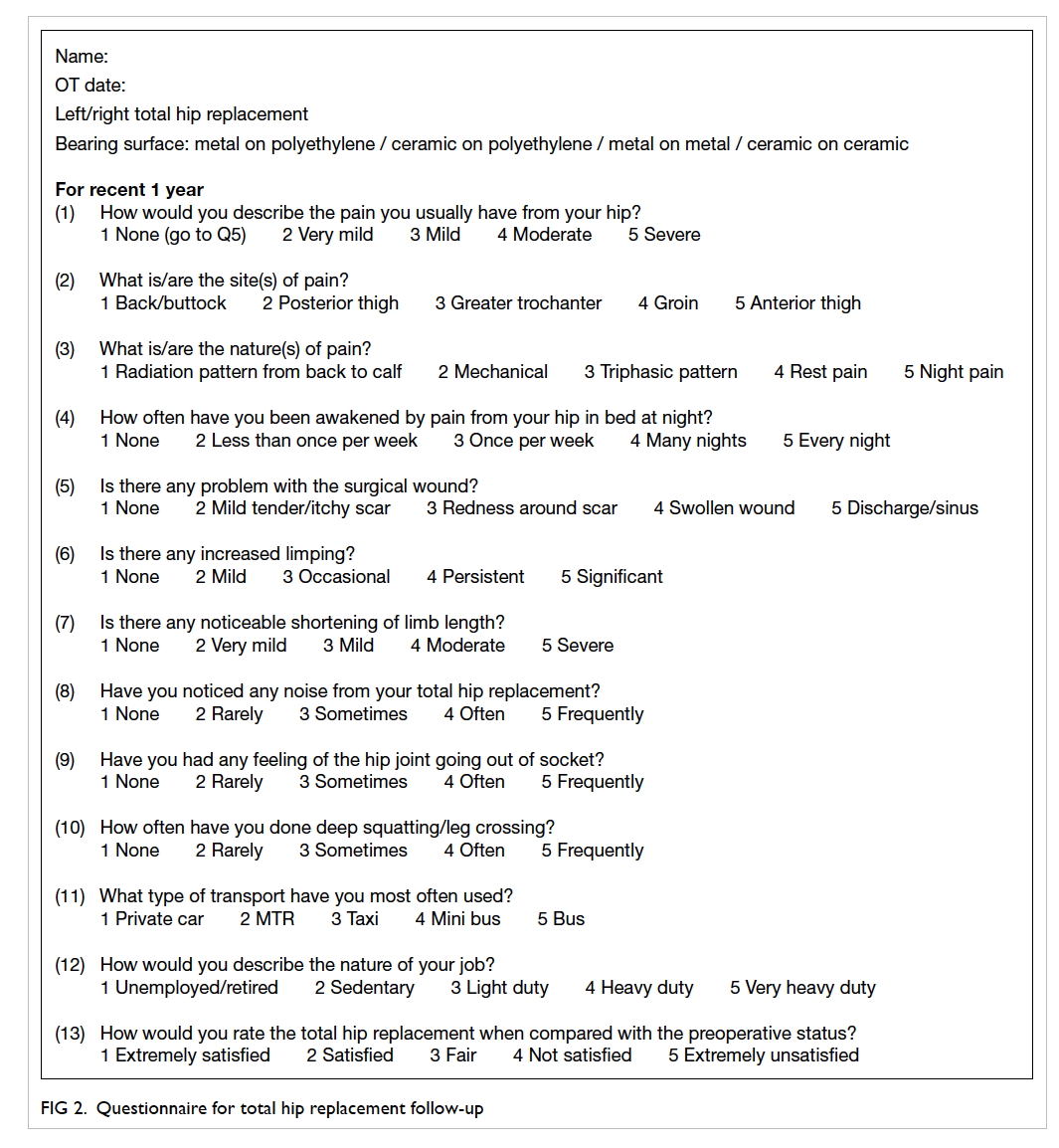

APN assessed the patients by TKR (Fig 1) or THR (Fig

2) questionnaire, charted KSKS or HHS, interpreted

follow-up radiographs, and then educated the patients

on care of and precautions with the prosthesis. The

findings were recorded in consultation notes in the

computer medical system (CMS). Patients were

managed according to the workflow (Fig 3). When the

TJR specialist was consulted on-site for any problem

related to the prosthesis, minor procedures like knee

aspiration could be done by the specialist at the same

consultation. After the clinic, the questionnaires and

the radiographs were screened by the specialist for

any significant problems.

The questionnaires were collected and the

consultation notes in CMS were studied. The

relevant data were then summarised and described

in an Excel file, including the number of cases of

TKRs and THRs, the number of on-site specialist

consultations, the number of prosthesis-related

complications diagnosed by the APN, the number

of patients referred to orthopaedic clinic and other

health care professionals, the number of medication

prescriptions, patients’ satisfaction, and patients’

acceptance of consultation without medication.

Patients’ waiting time for the clinic was also

obtained by calculating the difference between the

consultation time and the allocated time slot. The

CMS was also checked for any hospital admission

or clinic attendance for any problems related to TJR

after ACAC follow-up.

From November 2012 to April 2013, an APN,

one resident with specialist qualification (RS), and

one AC independently charted KSKS or HHS for

patients attending the preoperative assessment

clinic. Knee Society Knee Score is composed of

function score (FS) and knee score (KS)—FS is

made up of three components and KS is made up of

seven components. Harris Hip Score is composed of

17 components. Overall, 23 patients with 37 knees

and 11 patients with 17 hips were examined. In

order to analyse the inter-rater reliability between

the AC and APN (comparison A), between AC

and RS (comparison B), and between RS and APN

(comparison C), each component of the KSKS and

HHS was analysed for single-measure intraclass

correlation coefficient (ICC) and statistical

significance using the Statistical Package for the

Social Sciences (Windows version 15.0; SPSS Inc,

Chicago [IL], US). To see any statistically significant

difference between ICCs among the three groups

and between comparison A and international

standards,4 5 Fisher’s z-transformation was performed

by online calculator (www.vassarstats.net/rdiff.html).

Results

In the initial period from January to June 2012,

on-site specialist consultation was necessary in 21

(22.8%) cases out of the 92 cases (68 TKRs and 24

THRs). From July 2012 to March 2014, a total of 431

patients (including 317 TKRs and 114 THRs) were

managed and 408 (94.7%) nurse assessments were

independently performed. Six cases of prosthesis-related

complication were diagnosed including two

cases of patellar clunk in TKR, two cases of TKR

loosening, and two cases of THR loosening. Number

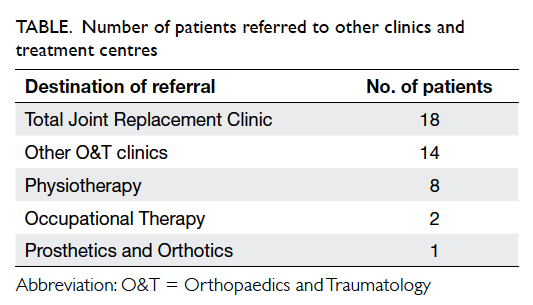

of referrals to other orthopaedic clinics and health

care professionals is shown in the Table. Among the 523 patients on ACAC follow-up, 131 (25.0%) requested medications. Average patient waiting time improved over the study period (26 minutes in December

2012, 18 minutes in April 2013, and 14 minutes in

March 2014). Of these 523 patients, 485 patients were interviewed; 354 were extremely satisfied and 131 were satisfied with ACAC follow-up by the nurse, and 373 (76.9%) patients accepted follow-up without drug prescription.

One patient who had undergone right TKR 12

years ago was hospitalised at 3 months after nurse

clinic follow-up because of sudden onset of right

knee effusion. X-ray showed no sign of prosthesis

loosening. Surgical exploration of the right knee

showed catastrophic wear of the polyethylene insert

while the prosthesis was stable. Two patients at 6

months after nurse assessment attended general out-patient

clinic for getting analgesics.

Study of reliability of the advanced practice

nurse in charting Knee Society Knee Score

and Harris Hip Score

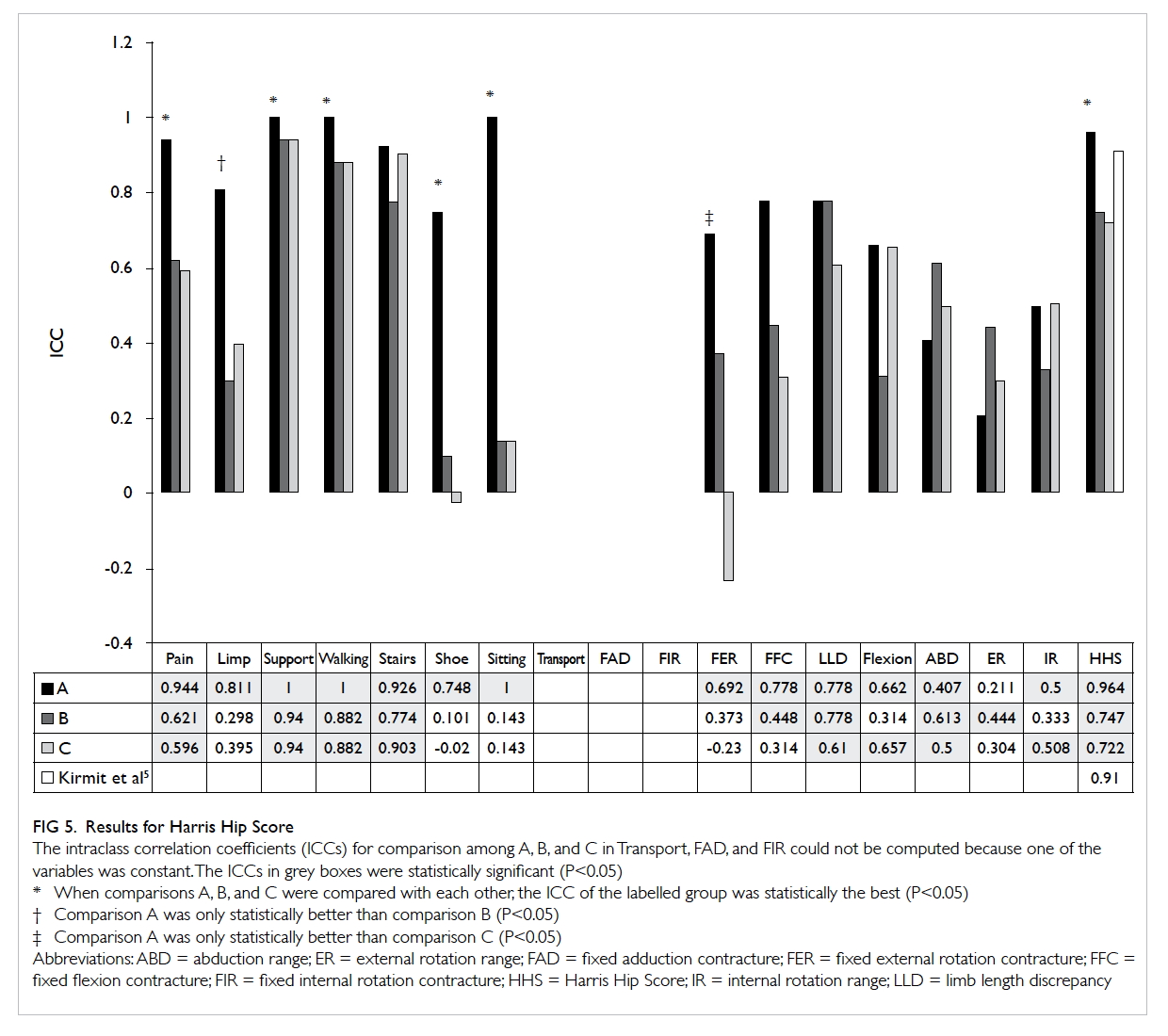

The result for KSKS is shown in Figure 4. The mean

ICCs were 0.912 (range, 0.660-0.987), 0.866 (range,

0.735-0.974), and 0.851 (range, 0.599-0.996)

for comparisons A, B and C, respectively. The

lowest ICC among all the components in KSKS was

that of mediolateral stability (0.599-0.797). When

comparing with those of Bach et al,4 the ICCs of

FS and all its components for comparison A were

significantly better. This was also the case for ICCs

of three of the five computable components of KS

and that of KS.

Figure 4. Results for Knee Society Knee Score

The ICCs for comparison among A, B, and C in AP and Ext lag could not be computed because one of the variables was constant. All the available ICCs for comparison between A and C were statistically significant (P<0.05)

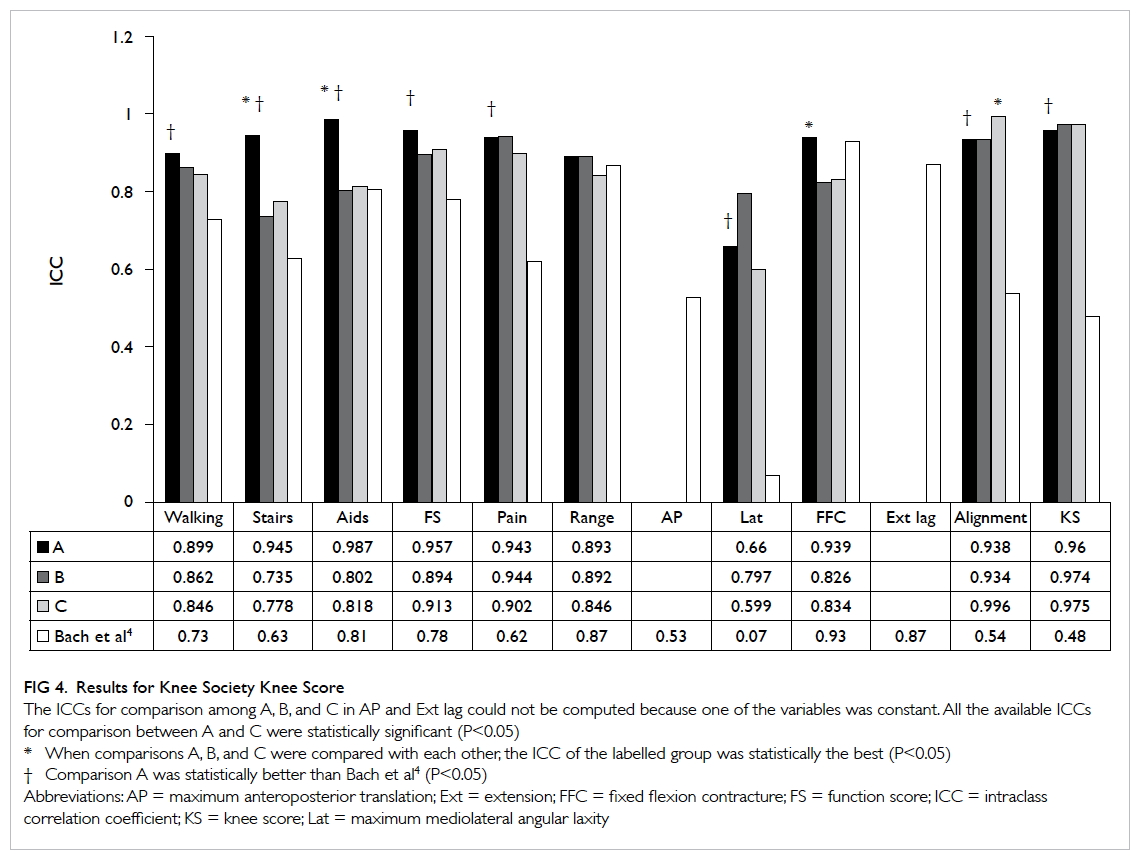

The result for HHS is shown in Figure 5.

The mean ICCs were 0.761 (range, 0.211-1) for

comparison A, 0.521 (range, 0.101-0.940) for

comparison B, and 0.481 (range, -0.231 to 0.940) for

comparison C. The ICCs for charting total HHS were

0.964, 0.747, and 0.722 for comparisons A, B and C,

respectively. When the ICC of comparison A (0.964)

was compared with that in the study by Kirmit et al5

(0.91), the difference was found to be statistically insignificant (P=0.124).

Discussion

In the current study, the well-trained APN

could independently handle 94.7% of the stable

postoperative cases in TJR after the initial learning

phase. She could successfully diagnose six cases

of prosthesis-related complications out of all the

523 patients she handled. One patient who was

asymptomatic at the ACAC follow-up presented

with sudden onset of right knee effusion, and showed

catastrophic wear of polyethylene. Nurse-led clinic

in TJR was, therefore, safe. It was well accepted by

patients with a 100% satisfaction rate. As the APN

grew more confident and gained more experience,

she also became more efficient. This, together with

improvement in workflow in taking radiographs, led

to progressive shortening of patient waiting time

from 26 minutes in the initial phase (December

2012) to 14 minutes in March 2014. It could greatly

relieve the burden of the specialist clinic. Within

2 years, 523 patient attendances were handled by

the APN. About five to seven cases were seen in

each session of this clinic. Moreover, more detailed

patient education, which is not possible in the busy

specialist clinic, can be provided to patients who

may have forgotten the details given several years

ago before the operation.

Bach et al4 studied the inter-observer correlation

of four commonly used TKR outcome scores—Hungerford score, Hospital for Special Surgery

score, Knee Society score, and Bristol score. Two

experienced orthopaedic surgeons independently

assessed 118 TKRs in 92 patients. The correlation

coefficient for mediolateral knee stability was the

lowest among all the components of all scoring

systems (0-0.38). This was due to the difficulty in

physical examination and proper measurement with

goniometer at the same time. For all the comparisons

in this study, we encountered the same difficulty

and found the same finding of lowest correlation

coefficient for mediolateral stability (0.599-0.797)

among all the components in KSKS. Kirmit et al5

evaluated the inter-observer reliability of five different

hip scores including HHS. Three physiotherapists

assessed 48 hips with osteoarthritis in 35 patients.

The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.82 to 0.91

for HHS, which was comparable to the result in

our study (0.722-0.964). With proper training of the

APN by the AC in this hospital, she could achieve

better or equally good correlation with the AC

as compared with an orthopaedic specialist and

international standard for charting KSKS and HHS.

In order to match the evolution of the health

care environments and patient care needs, the roles

and responsibilities of APNs have been reshaping.6

They have active and important places in taking

care of patients from various specialties. Their

contribution by running nurse-led clinics has been

shown to be tremendous in and outside Hong Kong.

They add value to patient care and complement

specialist clinics.3 7 8 9 Over 80% of their work are

independent of or interdependent with physicians

and involve skills such as adjusting medications, and

initiating therapies and diagnostic tests according to

protocols.3 10 To further advance professionalisation of nursing practice, Newey et al11 reported the training

of nurse practitioners to provide initial assessment in

clinics, perform carpal tunnel release, and manage

these patients in postoperative follow-up.

Shiu et al12 pointed out four boundaries

and six hindering factors for expanding advanced

nursing practice in nurse-led clinics. The

former included community-hospital, wellness-illness, public-private, and professional-practice

boundaries. The latter included stakeholder and

public awareness of advanced nursing practice role

in nurse-led clinics, provision of advanced specialty

education programmes, organisational support,

multidisciplinary collaboration, and changing

health care context and provision. When ACAC was

commenced, professional-practice boundary was the

first and the most important hurdle. The APN was

directly coached by an AC about various aspects in

TJR. The TKR and THR questionnaires and workflow

protocol were devised to facilitate the patient care

process. She was authorised to order standard

radiographs according to the region of interest,

and make referral to physiotherapy, occupational

therapy, prosthetics and orthotics, and the general

orthopaedic clinic. However, nurse prescription was

not possible and doctor prescription was necessary

in 25% of the cases. Getting help from doctors was

also required in a few cases for writing referral

letters to medical departments, applying for car park

permits for the disabled, applying for public housing,

and signing disability allowance forms. In order to

solve these remaining problems, there should be

appropriate legislation to redefine the professional

code of nursing practice, and organisational support

to offer a clear policy for nurse prescribing.12

Stakeholder and public awareness should be aroused

to allow inter-departmental referral and granting

public certification.

The second hurdle was the provision of

advanced specialty education programmes.

Currently, there is no programme or course in

universities and Hospital Authority teaching nurses

about TJR. Direct coaching was chosen as the training

method, and continuous education was provided to

broaden her exposure. This may be less than ideal and

a complete curriculum was not present. If the nurse-led

clinic were to be promoted and accepted as the

method to deal with the escalating workload from

various joint replacement centres, the Co-ordinating

Committee (COC), which is one of the Hospital

Authority Head Office committees for clinical

service, in orthopaedics and traumatology has to

collaborate with COC in nursing to formulate a good

training programme for nurses with special interest

in TJR. Knowledge of pharmacology is

also necessary for nurse prescription. The nursing

schools in various universities should revise the

curriculum to make nurse-led orthopaedic clinics

feasible and safe.

Conclusion

The success of nurse-led postoperative clinic in

TJR is multifactorial including the experience

and dedication of the APN, support of the trainer

specialist and department, a good working guideline

and protocol, and support of other health care

professionals. Its running is not perfect yet because

the specialty nurse cannot prescribe medications

and she is not community-recognised to sign

legal documents. However, such a clinic should

be established in Hong Kong to align with the

development of joint replacement centres in Hospital

Authority. Apart from the preoperative assessment

clinic and postoperative follow-up clinic, the trained

specialist nurse can also play important roles in

other stages of patient care. This requires further

exploration and collaboration with other health care

professionals.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Amy MY Cheng and Winnie YC Lam

for valuable inputs when setting up the nurse-led

clinic.

References

1. Wong FK. Health care reform and the transformation of

nursing in Hong Kong. J Adv Nurs 1998;28:473-82. CrossRef

2. Hospital Authority Annual Plan 2008-2009. Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Parent_ID=100&Content_ID=300&Dimension=100&Lang=ENG.

Accessed Aug 2010.

3. Wong FK, Chung LC. Establishing a definition for a nurse-led

clinic: structure, process, and outcome. J Adv Nurs

2006;53:358-69. CrossRef

4. Bach CM, Nogler M, Steingruber IE, et al. Scoring

systems in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res

2002;399:184-96. CrossRef

5. Kirmit L, Karatosun V, Unver B, Bakirhan S, Sen A, Gocen

Z. The reliability of hip scoring systems for total hip

arthroplasty candidates: assessment by physical therapists.

Clin Rehabil 2005;19:659-61. CrossRef

6. Bonsall K, Cheater FM. What is the impact of advanced

primary care nursing roles on patients, nurses and

their colleagues? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud

2008;45:1090-102. CrossRef

7. Larsson I, Bergman S, Fridlund B, Arvidsson B. Patients’

experiences of nurse-led rheumatology clinic in Sweden: a

qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci 2012;14:501-7. CrossRef

8. Slight C, Marsden J, Raynel S. The impact of a glaucoma

nurse specialist role on glaucoma waiting lists. Nurs Prax

N Z 2009;25:38-47.

9. Kirkwood BJ, Pesudovs K, Latimer P, Coster DJ. The

efficacy of a nurse-led preoperative cataract assessment

and postoperative care clinic. Med J Aust 2006;184:278-81.

10. Ng SL, Tse YB, Ho KL, Yiu MK. Efficacy of a Urology

Nurse-led Clinic in Queen Mary Hospital of Hong Kong.

Proceedings of the 11th Asian Congress of Urology of the

Urological Association of Asia; 2012 Aug 22-26; Pattaya,

Thailand. Int J Urol 2012;19(Suppl

1):432 abstract no. OP2512-07.

11. Newey M, Clarke M, Green T, Kershaw C, Pathak P. Nurse-led

management of carpal tunnel syndrome: an audit of

outcomes and impact on waiting times. Ann R Coll Surg

Engl 2006;88:399-401. CrossRef

12. Shiu AT, Lee DT, Chau JP. Exploring the scope of expanding

advanced nursing practice in nurse-led clinics: a multiple-case

study. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:1780-92. CrossRef