DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134155

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Digital ischaemia: a rare but severe complication of jellyfish sting

Stacey C Lam, BS, MB, ChB; YW Hung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery);

Esther CS Chow, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); Clara WY Wong, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); WL Tse, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); PC Ho, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Division of Hand and Microsurgery, Department of Orthopaedics, Prince of

Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YW Hung (ywhung@ort.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

We report a case of digital ischaemia in a 31-year-old

man who presented with sudden hand numbness,

swelling, and cyanosis 4 days after a jellyfish

sting. This is a rare complication of jellyfish sting,

characterised by a delayed but rapid downhill course.

Despite serial monitoring with prompt fasciotomy

and repeated debridement, he developed progressive

ischaemia in multiple digits with gangrenous change.

He subsequently underwent major reconstructive

surgery and aggressive rehabilitation. Although

jellyfish stings are not uncommon, no severe jellyfish

envenomation has been reported in the past in Hong

Kong and there has not been any consensus on the

management of such injuries. This is the first local

case report of jellyfish sting leading to serious hand

complications. This case revealed that patients who

sustain a jellyfish sting deserve particular attention

to facilitate early detection of complications and

implementation of therapy.

Case report

Our patient was a 31-year-old man with

unremarkable past health. He was swimming in the

waters of Phuket, Thailand, when he experienced

a sudden, intense burning pain in his right arm

and right thigh. He spotted a jellyfish in the water

after the incident. After getting out of the water, he

noticed immediate reddening and swelling over the

right thigh and right upper limb (from elbow down

to the hand). No systemic symptoms were reported.

The locals gave him some water to irrigate the sting

site and slathered a soothing cream on it. He was

then admitted to the local hospital and given a dose

of steroids.

The next day, he was discharged from the

local hospital and returned to Hong Kong. He was

admitted to the Department of Orthopaedics and

Traumatology of Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong

Kong, in July 2013. It was the second day after his

injury, and his right arm was swollen up to the

midarm, and there were multiple maculopapular

lesions over his right thigh and arm (Fig 1a, 1b). The injury site in the right forearm was explored

the same day, revealing healthy subcutaneous tissue,

fascia, and muscle (without features of necrotising

fasciitis). Wound swab culture was negative.

Figure 1. Serial photos showing progressive digital gangrene and large skin defect after repeated debridement

Typical lesion after jelly fish sting over (a) right thigh, (b) elbow, and (c) hand on day 2 after injury: linear; papular whip-like dermatitis (‘tentacle print’). (d) Finger tip with cyanotic changes on day 8 after injury. (e) Well-demarcated gangrenous change over finger tips on day 15 after injury. (f) Extensive skin defect with expose tendon after debridement on day 17 after injury. (g) Reconstruction included a two-stage operation with groin flap to cover the dorsum of hand and a second groin flap to cover gangrene tip (6 weeks after injury). (h) Outcome (attempt to make tight fist) after multiple major reconstruction (8 months after injury)

On the fourth day after the sting, he

experienced sudden onset of numbness and pain in

his right hand which rapidly progressed to almost

complete loss of sensation. The swelling in the right

arm and forearm also increased. The skin was cold

with cyanotic change in all fingers and the thumb;

capillary refill was sluggish (<4 seconds) but with

preserved turgor (Fig 1c). The radial pulse was not palpable. Compartment pressure measured

with Stryker needle revealed superficial flexor

compartment pressure of 35 mm Hg, deep flexor

compartment pressure of 25 mm Hg, and extensor

compartment pressure of 22 mm Hg.

Immediate fasciotomy of the right forearm

was done, revealing subcutaneous oedema but no

evidence of myonecrosis. Arteriotomy was not

performed in view of return of palpable radial and

ulnar pulse. Again, wound swab culture revealed no

bacterial growth. Biopsy revealed muscle necrosis

and infiltrate with white cells (predominantly

polymorph). Postoperatively, he was put in a warm

room with adequate fluid replacement and started

on subcutaneous fraxiparine.

Despite wound debridement and aggressive

medical treatment, 2 weeks after his initial insult,

his right hand circulation remained sluggish,

with progressive gangrenous change in the distal

phalanges of the thumb, index finger, middle finger,

half of the ring finger, and dorsum of the hand (Fig 1d, 1e). Computed tomography angiogram showed that the brachial artery was patent down to the palmar

arch level, suggesting distal small vessel disease. As

such, his gangrene would not be amenable to surgical

intervention. Finally, he had a staged reconstructive

surgery with distal amputation of his distal index

finger and thumb; a groin flap (distant pedicle

flap) was used to cover the major skin defect over

the dorsum of the hand and the thumb (Fig 1f, 1g).

With careful reconstructive surgery and aggressive

rehabilitation, 9 months after the incident, his right

hand regained movement, although it remained

functionally impaired with significant stiffness and

numbness (Fig 1h).

Discussion

Jellyfish belong to a family of Cnidaria found all

over the world. There are more than 2000 different

types of jellyfish, of which approximately 70 are

toxic to humans.1 The pathophysiology of jellyfish

sting is a combination of toxin and immunological

response (immediate allergic reaction and delayed

reaction).2 The toxins are composed of a mixture

of polypeptides and enzymes, leading to local or

systemic inflammatory responses.2 There has also

been a report on toxins causing platelet aggregation.3

Hence, the physiological response of jellyfish sting

depends on the species of jellyfish and the toxins

they release.

The toxin of Cnidaria is located in the

cnidocytes, which are stinging cells composed of

organelles called ‘nematocysts’. Nematocysts are

present on the outer surfaces of tentacles or near the

mouth. These are released when the victim’s skin is

in contact with jellyfish, injecting the venom into the

victim via a thread tube, sufficient to penetrate the

dermis of human skin.2

The majority of jellyfish stings are mild with

local skin reactions. The usual presentation is a

painful papular-urticaria at site of contact, which

looks like multiple whip-like eruptions. This is

compatible with the sting on the right leg in our case,

with a linear whip-like ‘tentacle print’. Lesions can

last for minutes or hours. Other local reactions also

include hyperhidrosis of skin, lymphadenopathy,

fat atrophy, vasospasm, gangrene, and contracture.

Systemic reactions—including gastro-intestinal

symptoms, cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest and

anaphylactic shock—are rare but not impossible.2

Hong Kong is a city surrounded by ocean. Many

people enjoy recreational water sports and, thus,

injury related to marine life is unavoidable. The latest

annual report by the Hong Kong Poison Information

Centre ranked venomous stings and bites as the

seventh commonest cause of poisoning.4 This is

likely an underestimation as most marine accidents

are managed at the scene, and this figure only takes

into account the ones reported. In the English

literature, there have only been three case reports of

serious jellyfish sting injuries leading to serious hand

or foot complications,5 6 7 and our case is the first local

case report. Similar to the sudden deterioration in

our patient, these documented cases all reported

patients who suffered from sudden oedema, cyanotic

changes, and weak pulse. This occurred around 3 to

4 days after the initial insult. In addition, the case

reported by Abu-Nema et al7 noted that the patient

had suffered from arterial spasm complicated by

thrombosis, and was subsequently treated with

urokinase. Our patient shares a similar complication

of vasospasm, as evidenced by patent but diminished

flow in distal arteries. It may be postulated that the

delayed vasospasm and possible thrombosis may

have led to this rare complication of jellyfish sting.

Although jellyfish injuries usually present with acute

skin reactions, our patient presented with clinical

deterioration of the hand on day 4 when the lower

limb skin reaction was actually improving.

The differences between our case and the other

case reports are in terms of alternative management

modalities and complications. Our patient received

fasciotomy, repeated debridement, and fraxiparine.

Some of the other authors incorporated other

surgical interventions such as cervicodorsal or

thoracic sympathectomy and medical treatments

such as dextran, prednisolone, reserpine, and

urokinase in case of thrombosis. Our patient suffered

from gangrenous thumb and fingers. In other case

reports, reported complications ranged from a

mere loss of superficial sensation, to amputation of

necrotic digits with Volkmann’s contracture.

Despite the adverse effects of cnidarian

stings, literature on treatment is limited and often

conflicting. It is difficult to perform high-quality

studies with sound methodology, owing to reasons

including limited number of cases and lack of

randomisation.8 The majority of cases are dealt with

at the scene by the general physician or accident and

emergency department. It is important for us to be

well equipped with management strategies for this

type of injury and maintain a high level of suspicion

for major complications. Our recommendations are

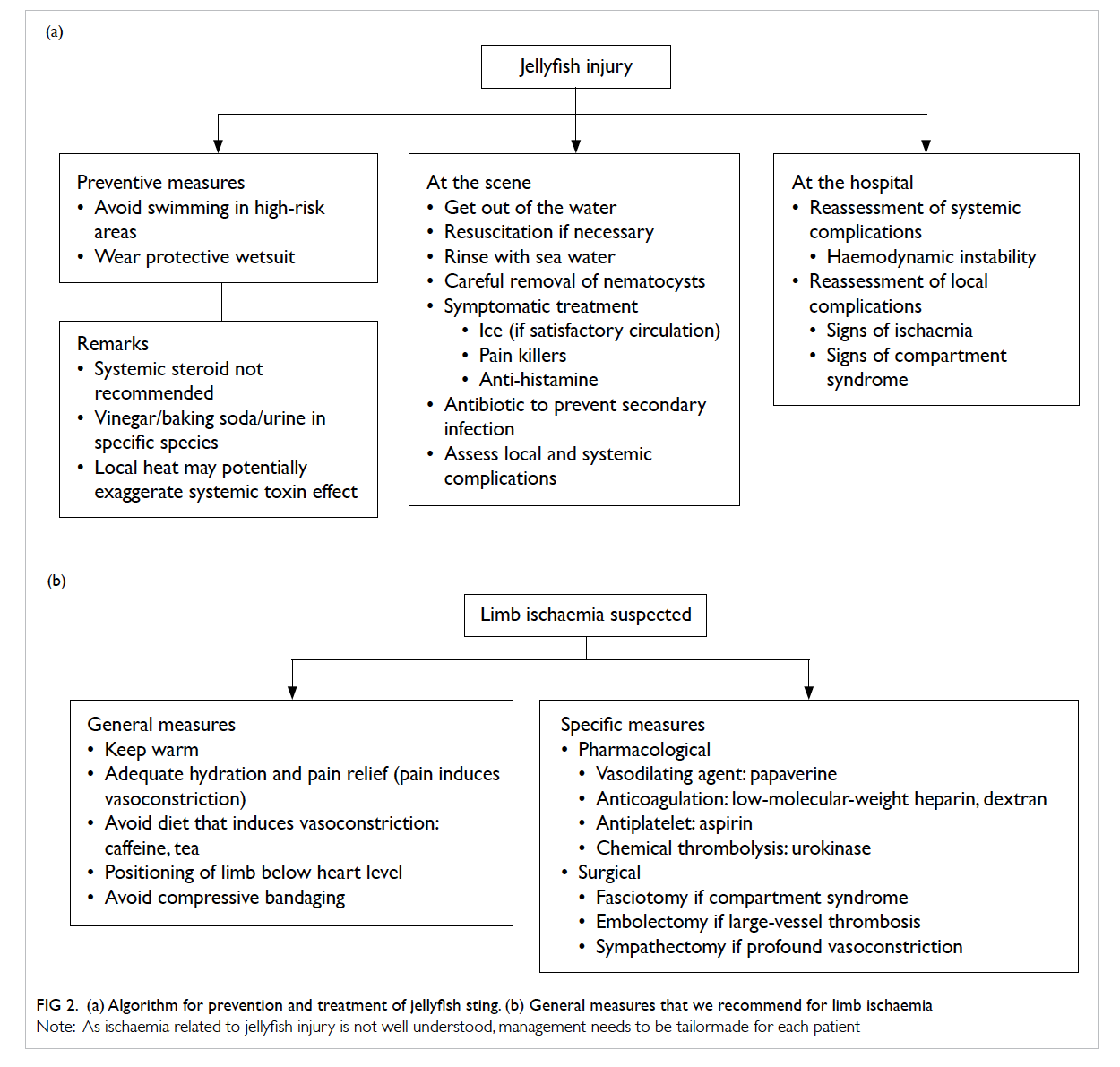

summarised in Figure 2a.

Figure 2. (a) Algorithm for prevention and treatment of jellyfish sting. (b) General measures that we recommend for limb ischaemia

Note: As ischaemia related to jellyfish injury is not well understood, management needs to be tailormade for each patient

The principles of the management of jellyfish

injury are:

(1) Best treatment remains prevention of injury

(2) Alleviate the local effect of venom (pain and

tissue damage)

(3) Prevent further discharge of nematocysts

(4) Control systemic reaction, including shock

Some important points need to be highlighted.

After rapid resuscitation, the next step is to remove

nematocysts, if technically feasible. It is also

important to note that popular home remedies such

as alcohol, physical rubbing by sand, or rinsing by

fresh water can actually worsen symptoms for the

victim, as these may lead to a massive nematocyst

discharge and toxin release. Another common folk

measure is the use of vinegar or urine to inactivate

the venom. Unfortunately, these two methods

are not applicable to all types of jellyfish stings as

different species have different toxins. We do not

recommend the general population to use either

vinegar or baking soda if the offending organism is

not well known.

Ice therapy is safe in general for pain relief due

to an unclear mechanism; whereas the application of

local heat is still debated, as it may potentially induce

vasodilation and a systemic toxic reaction rather

than denaturation of the venom. Anti-histamine

is generally safe for local symptom control and

antibiotics are also recommended for secondary

infection. There are no studies to support the use

of systemic corticosteroids in toxic reactions.8 Anti-venom

exists for a species of jellyfish called Chironex

fleckeri (sheep-derived whole immunoglobulin G).

However, it has unknown cardiotoxic effects and,

therefore, not approved or readily available.9

The underlying mechanism of local ischaemia

in our case was not well understood. Toxin- and

hypersensitivity-induced vasospasm and secondary

thrombosis are the postulated mechanisms. The

management algorithm in Figure 2b is based on this postulation. As there is no standardised management

in the literature, management should be tailored to

the patient and should balance the risks and benefits.

Further research is needed to confirm our postulation

and formulate a protocol for management of jellyfish

stings.

References

1. Brennan J. Jellyfish and other stingers. In: World Book’s

animals of the world. Chicago, IL: World Book, Inc;

2003.

2. Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Burnett HW. Jellyfish envenomation

syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;14:100-6. CrossRef

3. Azuma H, Sekizaki S, Satoh A, Nakajima T, Ishikawa M.

Platelet aggregation caused by a partially purified jellyfish

toxin from Carybdea rastonii. Toxicon 1986;24:489-99. CrossRef

4. Chan YC, Tse ML, Lau FL. Hong Kong Poison Information

Centre: Annual Report 2010. Hong Kong J Emerg Medicine

2012;19:110-20.

5. Giordano AR, Vito L, Sardella PJ. Complication of a

Portuguese man-of-war envenomation to the foot: a case

report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2005;44:297-300. CrossRef

6. Drury JK, Noonan JD, Pollock JG, Reid WH. Jelly fish sting

with serious hand complications. Injury 1980;12:66-8. CrossRef

7. Abu-Nema T, Ayyash K, Wafaii IK, Al-Hassan J, Thulesius

O. Jellyfish sting resulting in severe hand ischaemia

successfully treated with intra-arterial urokinase. Injury

1988;19:294-6. CrossRef

8. Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, Mastrangelo G.

Jellyfish stings and their management: a review. Mar Drugs

2013;11:523-50. CrossRef

9. Balhara KS, Stolbach A. Marine envenomations. Emerg

Med Clin North Am 2014;32:223-43. CrossRef