DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134085

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Novel use of idebenone in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy in Hong Kong

SW Cheng, MB, ChB, MRCPCH1; CH Ko, FHKAM (Paediatrics), FRCP RCPS (Glasg)1; SK Yau, MB, ChB, FRCSEd2; Chloe Mak, MD, PhD3; YF Yuen, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)2; CY Lee, FHKAM (Paediatrics), FRCP (Edin)1

1 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Caritas Medical

Centre, Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology, Caritas Medical Centre, Shamshuipo,

Hong Kong

3 Department of Pathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong

Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SW Cheng (csw350@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

We report a case of a young Chinese male presenting

with sequential, painless, bilateral visual loss in Hong

Kong. He was diagnosed to have Leber’s hereditary

optic neuropathy with genetic workup showing

G11778A mutation with over 80% heteroplasmy.

He was started on idebenone treatment 11 months

after onset of the binocular disease. To our best

knowledge, this is the first case of Leber’s hereditary

optic neuropathy treated with idebenone in Hong

Kong. The recent evidence of the diagnosis and

treatment of this devastating disease is reviewed.

Introduction

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is the

commonest mitochondrial disease found to affect

around 1 in 30 000 people in the first population-based

clinical and molecular genetic study carried

out in the UK.1 It is characterised by sequential

bilateral visual loss, optic nerve dysfunction, and

retinal ganglion cell degeneration. Characteristic

visual field defect in LHON includes either central or

cecocentral scotomas. Approximately 70% of patients

were found to be young adults in the UK study. Over

20 mitochondrial DNA point mutations have been

reported in LHON worldwide.2 Around 95% of the

LHON pedigree have one of the three mitochondrial

DNA point mutations namely, G3460A, G11778A,

and T14484C, which are responsible for coding of

complex I subunits of the mitochondrial respiratory

chain.

Case report

A 15-year-old Chinese male, with a history of

congenital red-green colour blindness, presented

with sudden blurring of right eye central vision in

August 2011. He did not experience any ocular pain

or photopsia. There was no family history of ocular

or neurological diseases.

On admission, his visual acuity was 6/120

in the right eye and 6/6 in the left eye. Right-eye

visual field examination showed central scotoma

associated with right relative afferent papillary

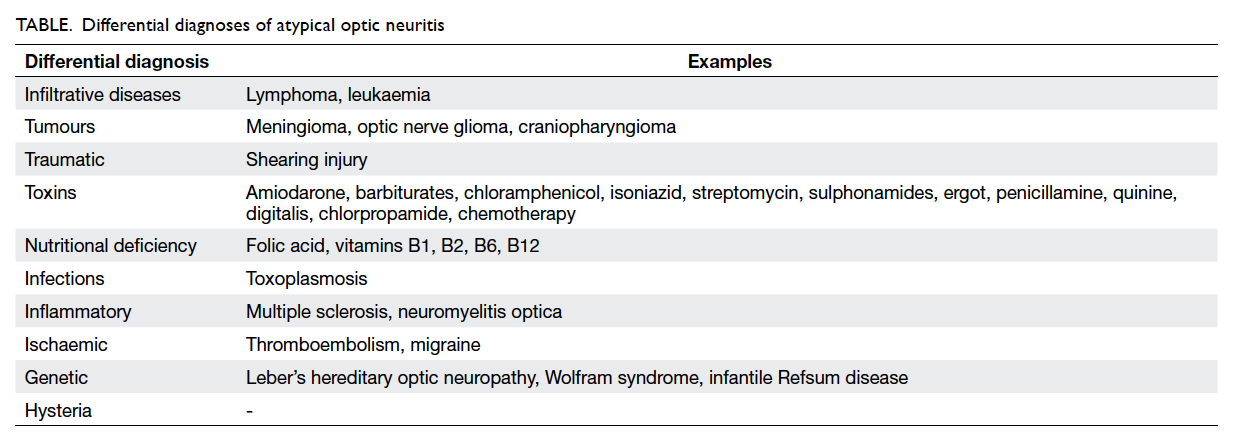

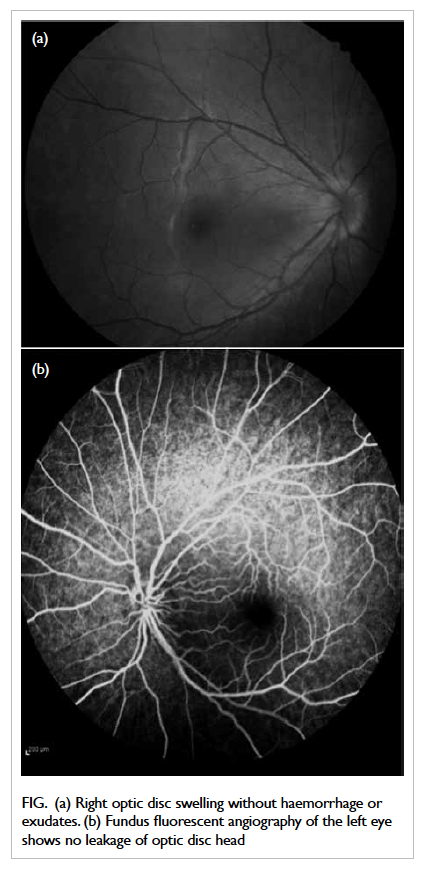

defect. Fundoscopy revealed right eye disc swelling

without peripapillary haemorrhage or exudate (Fig a). Neurological and cardiovascular examinations

were normal.

Figure. (a) Right optic disc swelling without haemorrhage or exudates. (b) Fundus fluorescent angiography of the left eye shows no leakage of optic disc head

Perimetry revealed right centrocecal scotoma.

Computed tomography of brain and orbit with

contrast showed normal eye globes and extra-ocular

muscles but mildly thickened intra-orbital right optic

nerve suggestive of right optic neuritis. Erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were not

elevated. Blood test for anti-nuclear antibody was

negative. Serologies for toxoplasmosis, herpes virus,

Lyme disease and syphilis as well as tuberculin test

were negative. Visual evoked potential revealed

prolonged P100 over the right eye compatible with

optic neuropathy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the

brain and orbit was unremarkable. The patient was

diagnosed to have optic neuritis and recommended

for steroid treatment according to Optic Neuritis

Treatment Trial (ONTT).3 However, his parents

declined the treatment due to the possible side-effects

of steroids.

Two months later, the patient experienced

sudden painless blurring of left eye central vision.

Visual acuity was 6/60 in the left eye while it

remained at 6/120 in the right eye. Cerebrospinal

fluid examination revealed normal biochemistry and

cell count, and was negative for oligoclonal bands.

Serum folate and vitamin B12 levels were normal.

He was started on an ONTT-recommended dose of

intravenous methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day) for

3 days, followed by oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day)

for 11 days. However, his visual function deteriorated

despite treatment. In view of the atypical features

of sequential visual bilateral optic neuritis without

recovery, LHON was suspected and confirmed

by identification of mitochondrial DNA point

mutation at 11778 guanine to adenine in the blood,

with high mutant load heteroplasmy (over 80%).

Fundus fluorescent angiography revealed left-disc

telangiectatic vessels without optic disc head leakage

compatible with typical angiographic features of

LHON (Fig b).

He was then put on high-dose oral antioxidants

(vitamin C 500 mg daily and co-enzyme Q10

ubiquinone). The medication was switched to

idebenone 900 mg per day in divided doses when the

drug became available in the hospital.

Six months after treatment with idebenone,

his visual acuity remained static: 1/60 and 2/60 in

the right and left eye, respectively. There were no

side-effects related to the treatment. He gradually

adapted to school life, with improvement in using

Braille. Genetic study revealed the mother to be a

LHON carrier (G11778A). His sister refused genetic

testing due to the possible implications on future

employment and academic considerations.

Discussion

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory disease of the optic

nerve. It is the second commonest acquired optic

nerve disorder in persons under 50 years old. The typical

presenting symptom includes sudden visual loss

with dyschromatopsia over several hours to days.

This may be associated with dull retrobulbar pain

which worsens with ocular movement. Symptoms

can occur in both eyes either simultaneously or

sequentially. A clinical diagnosis of optic neuritis may

be made based on the following signs and symptoms:

sudden visual loss with progression within 1 week,

dyschromatopsia, pain on extra-ocular movement,

no features of uveitis, and vision improvement

beginning in 3 to 4 weeks.4 According to the findings

in ONTT, 80% of patients with optic neuritis will

improve within the first 3 weeks.5 Over 95% will

regain visual acuity of at least 20/40, regardless of

treatment options at 12 months’ time from onset of

symptoms.6 The initial presentation of our patient

was similar to that of optic neuritis. However, failure

of spontaneous recovery in the absence of other

causes should alert the clinician to consider atypical

optic neuritis. The differential diagnoses of atypical

optic neuritis are listed in the Table. A detailed

history and clinical examination helps to understand

the underlying aetiology, which may be confirmed

by relevant radiological, serological, bacteriological,

electrophysiological, and molecular investigations.

Patients with LHON experience devastating

visual loss, typically worse than 20/200 in both eyes.

At least 97% of patients will have sequential eye

involvement within 1 year.7 Over 90% of patients

harbour one of the three pathogenic mitochondrial

mutations (G3460A, G11778A, T14484C), which

affect complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory

chain.8 The pathogenesis of LHON involves a

combination of decreased complex I–driven

adenosine triphosphate production, increase in free

radical production and, finally, retinal ganglion cell

apoptosis.9 The most important prognostic factor for

visual recovery is the mutation status. The T14484C

mutation carries the best chance of some degree of

visual improvement in 37% to 71% of patients, while

the G11778A mutation is associated with only 4%

chance of recovery.7

Kirkman et al10 suggested that visual loss

occurs more often in smokers and people with high

alcohol intake. It is essential to advise patients to

avoid tobacco smoking, excessive alcohol intake,

and medications that may have mitochondrial

toxicity (eg aminoglycosides, metformin, statins),

especially during the acute phase of visual loss.

Directed therapies for mitochondrial disorders are

very limited. To date, there is no effective treatment

for LHON. The mainstay of management remains

supportive, such as low visual aids to assist reading,

communication, and employment.

Anecdotal reports have shown beneficial effects

of idebenone, which is a short-chain benzoquinone

structurally related to co-enzyme Q10. It is a potent

antioxidant and inhibitor of lipid peroxidation. It

facilitates mitochondrial electron flux in bypassing

complex I.11 In a retrospective open-label study

involving 28 LHON patients, Mashima et al12

reported significantly shortened onset of visual

recovery (11.1 months vs 17.4 months; P=0.03) and

shortened interval for recovery of vision to ≥0.3 (17.6

months vs 34.4 months; P=0.01) in the treated group

versus the untreated group. Jancic13 administered

idebenone to nine patients at 135 mg/day for

up to 1 year. Three patients reported subjective

improvement in visual acuity, one with monocular

disease showed arrest of progression of visual loss to

the other eye, and four demonstrated improvement

in visual evoked potential. Klopstock et al14

conducted a 24-week multicentre double-blind,

randomised, placebo-controlled trial in 85 patients

given idebenone at a dose of 900 mg/day. There was

no significant difference in the overall group for best

recovery of visual acuity. However, in the subgroup

with discordant visual acuities at baseline (n=30), a

significant trend for improvement in visual acuity

was observed in the treated group. Idebenone was

well tolerated with no adverse effect. In summary,

current evidence suggests that idebenone is probably

beneficial in the early-stage LHON patients with

discordant visual acuities, and may help to shorten

the interval of visual recovery.

In our patient, the static eye condition in the

initial 6 weeks had prompted extensive diagnostic

investigations including molecular study. However,

the patient developed binocular involvement 2

months after onset of the symptoms. As idebenone

was not available with the local pharmaceutical

company, ordering of the drug from overseas had

involved time and administrative process. The poor

response of visual symptoms to idebenone might be

explained by the late introduction of the treatment,

in this case, 11 months after binocular involvement.

In our patient, the interval from disease onset

till binocular involvement was only 2 months.

Heightened physician awareness is important to

identify this devastating condition during this

interval, which may represent the golden window

for initiation of idebenone to prevent sequential

visual loss and hasten recovery. Molecular analysis

for the three common mutations, which is available

locally, aids definitive diagnosis, prognostication,

and detection of presymptomatic family members.

Those presymptomatic family members with

positive mutation require lifelong surveillance,

lifestyle modification, and prompt intervention at

disease onset.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms Josephine

Lui, pharmacist of Caritas Medical Centre, for her

arduous effort to source idebenone for this patient.

References

1. Man PY, Griffiths PG, Brown DT, Howell N, Turnbull DM,

Chinnery PF. The epidemiology of Leber hereditary optic

neuropathy in the North East of England. Am J Hum Genet

2003;72:333-9. CrossRef

2. Brown MD, Wallace DC. Spectrum of mitochondrial DNA

mutations in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Clin

Neurosci 1994;2:138-45.

3. Beck RW, Cleary PA, Anderson MM Jr, et al. A randomized,

controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute

optic neuritis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. N Engl J

Med 1992;326:581-8. CrossRef

4. Gal RL, Vedula SS, Beck R. Corticosteroids for treating optic

neuritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(4):CD001430.

5. Beck RW, Cleary PA, Backlund JC. The course of visual

recovery after optic neuritis. Experience of the Optic

Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology 1994;101:1771-8. CrossRef

6. Beck RW, Cleary PA. Optic neuritis treatment trial. One-year

follow-up results. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:773-5. CrossRef

7. Newman NJ, Biousse V, David R, et al. Prophylaxis

for second eye involvement in Leber hereditary optic

neuropathy: an open-labeled, nonrandomized multicenter

trial of topical brimonidine purite. Am J Ophthalmol

2005;140:407-15. CrossRef

8. Harding AE, Sweeney MG, Govan GG, Riordan-Eva P.

Pedigree analysis in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy

families with a pathogenic mtDNA mutation. Am J Hum

Genet 1995;57:77-86.

9. Fraser JA, Biousse V, Newman NJ. The neuro-ophthalmology

of mitochondrial disease. Surv Ophthalmol

2010;55:299-334. CrossRef

10. Kirkman MA, Yu-Wai-Man P, Korsten A, et al. Gene-environment

interactions in Leber hereditary optic

neuropathy. Brain 2009;132:2317-26. CrossRef

11. Haefli RH, Erb M, Gemperli AC, et al. NQO1-dependent

redox cycling of idebenone: effects on cellular redox

potential and energy levels. PLoS One 2011;6:e17963. CrossRef

12. Mashima Y, Kigasawa K, Wakakura M, Oguchi Y. Do

idebenone and vitamin therapy shorten the time to achieve

visual recovery in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy? J

Neuroophthalmol 2000;20:166-70. CrossRef

13. Jancic J. Effectiveness of idebenone therapy in Leber’s

hereditary optic neuropathy. Proceedings of 11th

European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP)

Regional Meeting; 2011 Apr 14-16; St. Petersburg, Russian

Federation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2011; 21: S175.

14. Klopstock T, Yu-Wai-Man P, Dimitriadis K, et al. A

randomized placebo-controlled trial of idebenone in

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2011;134:2677-86. CrossRef