DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134127

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Primitive neuroectodermal adrenal gland tumour

YP Tsang, MB, ChB, MRCS(Ed); Brian HH Lang, MS, FRACS; SC Tam, MB, BS, MRCS(Ed); KP Wong, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Gen)

Division of Endocrine Surgery, Department of Surgery, Queen Mary

Hospital, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Brian HH Lang (blang@hku.hk)

Abstract

Ewing’s sarcoma, also called primitive

neuroectodermal tumour of the adrenal gland, is

extremely rare. Only a few cases have been reported

in the literature. We report on a woman with adult-onset

primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the

adrenal gland presenting with progressive flank

pain. Computed tomography confirmed an adrenal

tumour with invasion of the left diaphragm and

kidney. Radical surgery was performed and the

pain completely resolved; histology confirmed the

presence of primitive neuroectodermal tumour, for

which she was given chemotherapy. The clinical

presentation of this condition is non-specific, and

a definitive diagnosis is based on a combination

of histology, as well as immunohistochemical and

cytogenic analysis. According to the literature, these

tumours demonstrate rapid growth and aggressive

behaviour but there are no well-established

guidelines or treatment strategies. Nevertheless,

surgery remains the mainstay of local disease control;

curative surgery can be performed in most patients.

Adjuvant chemoirradiation has been advocated yet

no consensus is available. The prognosis of patients

with primitive neuroectodermal tumours remains

poor.

Introduction

Ewing’s sarcoma (ES), also called primitive

neuroectodermal tumours (PNET), is a rare cancer

of presumed neuroectodermal origin and is mostly

found in children and young adults.1 Since it usually

involves the diaphysis of long bones, adrenal ES/PNET is extremely rare. To our knowledge, only a

handful of cases have been reported in the literature.

Herein we present a patient with adult-onset adrenal

PNET and discuss the diagnostic and management

issues.

Case report

A 37-year-old woman presented to our hospital

in May 2013 with progressive pain over left flank

and abdomen for 1 month. Physical examination

revealed a ballotable mass over the left flank.

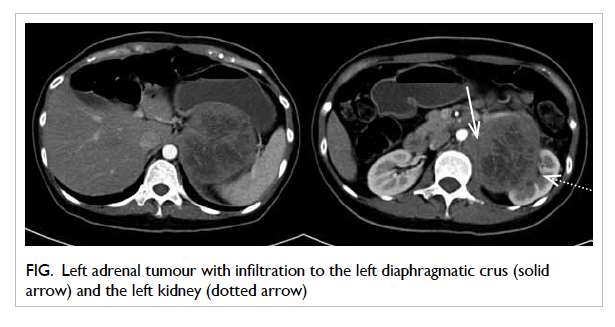

Contrast computed tomography (CT) demonstrated

a 12-cm left adrenal mass with infiltration to the left

crus of diaphragm and upper pole of the left kidney

(Fig). On closer examination, the left renal artery was encased by the tumour but there was no evidence

of distant metastases. Hormonal workup of this

adrenal mass suggested that it was a non-functioning

tumour. There was no excess in 24-hour urinary

catecholamines and metanephrines, while 24-hour

urinary free cortisol excretion was 71 (reference range

[RR], 24-140) nmol. The aldosterone-renin ratio

was 9.0 (reference level, <20) ng/dL per ng/(mL•h).

Luteinising hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone,

and testosterone levels were 3.0 (RR, 1.2-103.0) IU/L,

6.8 (1.8-22.5) IU/L, and 0.83 (0.35-2.60) nmol/L,

respectively. The dehydroepiandrosterone level was 4.5 (RR, 2-11) µmol/L. Owing to increasing pain

and the rapidly growing tumour, she underwent

surgery, which revealed a 12-cm adrenal tumour

compressing the aorta and superior mesenteric

artery, and the posterior part of the diaphragm and

left renal artery were invaded by the tumour bulk.

Accordingly, she underwent a left adrenalectomy

together with radical nephrectomy and partial

resection of the diaphragm. No gross tumour was

left behind. Thereafter, she made a good uneventful

recovery and was discharged on the fifth day. Her

back pain resolved completely after surgery.

Figure. Left adrenal tumour with infiltration to the left diaphragmatic crus (solid arrow) and the left kidney (dotted arrow)

Histology revealed a monotonous population

of small round tumour cells with hyperchromatic

nuclei, small nucleoli, and minimal cytoplasm

arranged in sheets and cords with occasional

vague rosette formation. Karyorrhexis, mitosis,

and ‘starry sky’ pattern were focally observed.

Immunohistochemically, the tumour cells stained

positively for MIC2 antigen (CD99), vimentin,

and FLI1. By contrast they stained negatively for

cytokeratin, leukocyte common antigen, MPO, WT1,

synaptophysin, S100, desmin, myogenin, CD68, and

CD34. The reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain

reaction confirmed a reciprocal translocation of

t(11;22)(q24;q12) involving the EWSR1 gene on

chromosome 22 and the FLI1 gene on chromosome

11 (ie EWSR1-FLI1 translocation). Overall, these

findings were consistent with ES/PNET.

She received adjuvant chemotherapy

(cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, and vincristine

alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide). The latest

CT at 5 months post-surgery revealed no evidence of

local or distant recurrence.

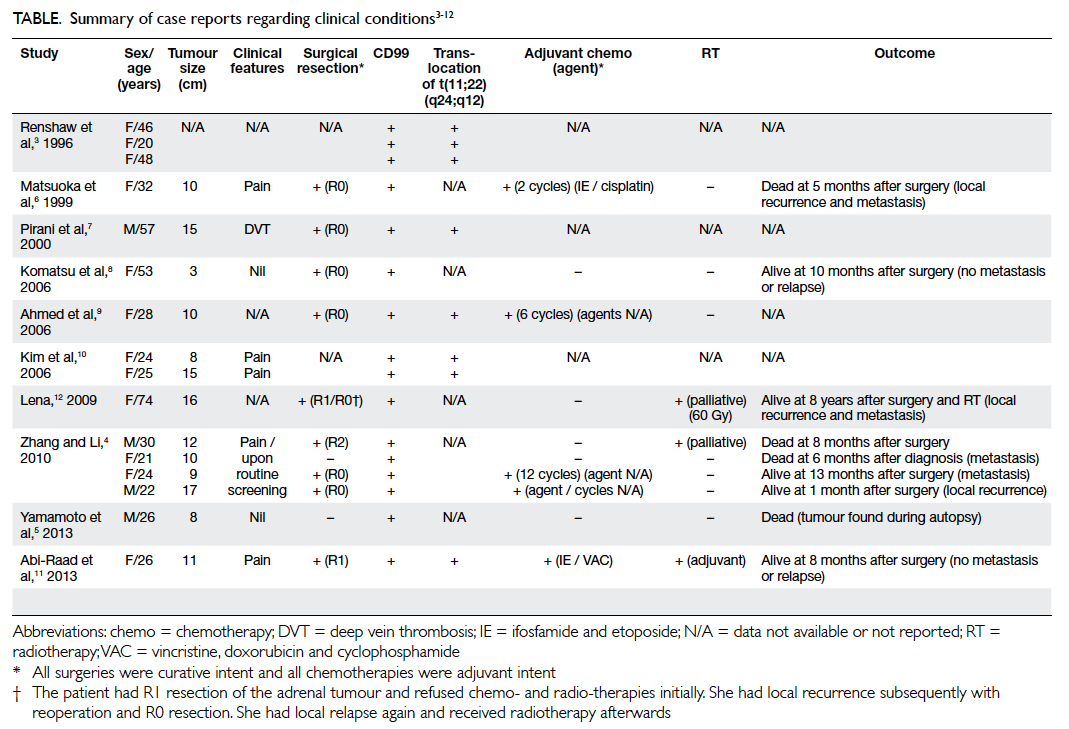

Discussion

Ewing’s sarcoma/PNET of the adrenal gland is rarely

reported.2 3 Our review of the English literature

revealed only 10 reports describing 16 patients

(Table).3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 As in our patient, CD99, a highly sensitive

marker for PNET, was found in all 16 of these

patients. Although not routinely looked for, as in our

patient over 90% of PNET cases exhibit a reciprocal

translocation of t(11;22)(q24;q12) involving the

EWSR1 gene on chromosome 22 and the FLI1 gene

on chromosome 11.1 3 6 7 8 9 11 12 These 16 reported cases

had a median age at diagnosis of 26 (range, 20-74)

years, and the female-to-male ratio was 3:1. The

median tumour size was 10.5 (range, 3-17) cm.

Nine of these patients underwent curative

surgery despite rapid growth and aggressive tumour

behaviour.4 7 8 12 13 Nevertheless, in a few patients

the tumour behaves indolently or has a relatively quiescent period before rapid growth. A case of

incidental PNET at autopsy has been reported in a 26-year-old man who committed suicide by hanging himself; his latent PNET measured 8 cm.5 Similarly, another patient aged 53 years underwent a laparoscopic adrenalectomy for a presumed non-functional incidental adrenocortical adenoma, but turned out to be a 3-cm PNET.8

Diagnostic issues

It is difficult to make a definitive diagnosis of ES/PNET before surgery because currently it is based on a combination of histology, immunohistochemistry, and cytogenetic analysis.4 8 Although needle biopsy is a possible approach to making a definitive diagnosis

without resection, it is rarely performed unless the tumour is considered not resectable or adrenal

metastases are suspected. Since our patient had a potentially resectable tumour with no evidence

of distant metastases, needle biopsy was not considered. Furthermore, she was clearly suffering

pain arising from the tumour and therefore surgical resection was clearly indicated.

Management issues

Due to its rarity, there are no well-established

guidelines or treatment strategies for PNET. Surgical

resection remains the mainstay for local disease

control.4 7 8 Since the tumour is believed to be both

chemo- and radio-sensitive, adjuvant chemotherapy

and radiotherapy have often been advocated for

better local and distant control, but there is no

consensus.13 A standard regimen of chemoirradiation

is not yet established due to the sporadic nature of

cases.13 Most chemotherapy regimens for adult-onset

PNET are akin to those for ES in children as both share the same origin.4 14 Chemotherapeutic agents such as cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine,

ifosfamide, or etoposide have been used.4 7 8 Recently, it has been noted that chemotherapy might be

effective only for the first few cycles, and that the tumours develop resistance very quickly.4 Adjuvant radiotherapy had been used for local recurrences as well as unresectable or incompletely resected

PNETs.4 12 From our review, adrenalectomies were

performed for 11 patients, while chemotherapy and radiotherapy was also given to six and three of

them, respectively. Follow-up revealed that these tumours were aggressive; three of the 16 patients

died within 1 year of diagnosis or surgery. Regarding the six patients who were still surviving when this

report was submitted, one had distant metastasis and another two had local recurrence. Because of

this high rate of recurrence, intensive follow-up with regular CT scans (every 6 months) has been

advocated even after seemingly curative surgery.12

Conclusion

Herein we report a rare case of adult adrenal PNET. The clinical presentation is often vague and non-specific and a definitive diagnosis depends on a combination of histology, immunohistochemistry, and cytogenetic analysis. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment coupled with adjuvant chemoirradiation. Nevertheless, the prognosis

appears poor.

References

1. Grier HE. The Ewing family of tumors. Ewing’s sarcoma

and primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Pediatr Clin North

Am 1997;44:991-1004. CrossRef

2. Quezado M, Benjamin DR, Tsokos M. EWS/FLI-1 fusion

transcripts in three peripheral primitive neuroectodermal

tumors of the kidney. Hum Pathol 1997;28:767-71. CrossRef

3. Renshaw AA, Perez-Atayde AR, Fletcher JA, Granter SR.

Cytology of typical and atypical Ewing’s sarcoma/PNET.

Am J Clin Pathol 1996;106:620-4.

4. Zhang Y, Li H. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of

adrenal gland. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:800-4. CrossRef

5. Yamamoto T, Takasu K, Emoto Y, et al. Latent adrenal

Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: a case report. Leg Med

(Tokyo) 2013;15:96-8. CrossRef

6. Matsuoka Y, Fujii Y, Akashi T, Gosehi N, Kihara K.

Primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the adrenal gland.

BJU Int 1999;83:515-6. CrossRef

7. Pirani JF, Woolums CS, Dishop MK, Herman JR. Primitive

neuroectodermal tumor of the adrenal gland. J Urol

2000;163:1855-6. CrossRef

8. Komatsu S, Watanabe R, Naito M, et al. Primitive

neuroectodermal tumor of the adrenal gland. Int J Urol

2006;13:606-7. CrossRef

9. Ahmed AA, Nava VE, Pham T, et al. Ewing sarcoma family

of tumors in unusual sites: confirmation by rt-PCR. Pediatr

Dev Pathol 2006;9:488-95. CrossRef

10. Kim MS, Kim B, Park CS, et al. Radiologic findings of

peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor arising in the

retroperitoneum. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:1125-32. CrossRef

11. Abi-Raad R, Manetti GJ, Colberg JW, Hornick JL, Shah JG,

Prasad ML. Ewing sarcoma/PNET arising in the adrenal

gland. Pathol Int 2013;63:283-6. CrossRef

12. Lena M. Retroperitoneal primitive neuroectodermal

tumour (PNET). A case report and review of the literature.

Rep Practical Oncol Radiother 2009;14:221-4. CrossRef

13. Malpica A, Moran CA. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of

the cervix: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical

study of two cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 2002;6:281-7. CrossRef

14. Bisogno G, Carli M, Stevens M, et al. Intensive

chemotherapy for children and young adults with

metastatic primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the soft

tissue. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002;30:297-302. CrossRef