Hong Kong Med J 2014 Oct;20(5):379–85 | Epub 6 Jun 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in patients

with primary open-angle glaucoma

Ege G Balbay, MD1; Oner Balbay, MD1; Ali N Annakkaya, MD1; Kezban O Suner, MD1; Harun Yuksel, MD2; Murat Tunç, MD2; Peri Arbak, MD1

1 Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Düzce University, 81620 Düzce, Turkey

2 Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Düzce University, 81620 Düzce, Turkey

This study was presented as thematic poster in the 21st European

Respiratory Society Annual Congress in Amsterdam, The Netherlands,

24-28 Sep 2011. The abstract was published in European Respiratory

Journal 2011;38(Suppl 55):2253.

Corresponding author: Dr Ege G Balbay (egegulecbalbay@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the prevalence of

obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in patients with

primary open-angle glaucoma.

Design: Case series.

Setting: School of Medicine, Düzce University,

Turkey.

Patients: Twenty-one consecutive primary

open-angle glaucoma patients (12 females and 9

males) who attended the out-patient clinic of the

Department of Ophthalmology between July 2007

and February 2008 were included in this study. All

patients underwent polysomnographic examination.

Results: The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea

syndrome was 33.3% in patients with primary

open-angle glaucoma; the severity of the condition

was mild in 14.3% and moderate in 19.0% of the

subjects. The age (P=0.047) and neck circumference

(P=0.024) in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea

syndrome were significantly greater than those

without the syndrome. Triceps skinfold thickness in

glaucomatous obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome

patients reached near significance versus those

without the syndrome (P=0.078). Snoring was

observed in all glaucoma cases with obstructive

sleep apnoea syndrome. The intra-ocular pressure

of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma

with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome was

significantly lower than those without obstructive

sleep apnoea syndrome (P=0.006 and P=0.035 for

the right and left eyes, respectively). There was no significant difference in the cup/disc ratio and visual

acuity, except visual field defect, between primary

open-angle glaucoma patients with and without

obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome.

Conclusions: Although it does not provide evidence

for a cause-effect relationship, high prevalence

of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in patients

with primary open-angle glaucoma in this study

suggests the need to explore the long-term results

of coincidence, relationship, and cross-interaction of

these two common disorders.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Although this study did not provide an evidence for a cause-effect relationship between obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) and primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), the high prevalence of OSAS in patients with POAG might present a new perspective to ophthalmologists when managing glaucoma patients.

- In clinical practice, OSAS is often not taken into diagnostic consideration for glaucoma patients. The high prevalence of OSAS in patients with POAG might present a new perspective to ophthalmologists and encourage them to explore the long-term results of coincidence, relationship, and cross-interaction of these two common disorders. Based on data from the present study, we recommend eliciting history of sleep apnoea symptoms in patients with glaucoma, especially in those who are obese and have thick necks. We also recommend polysomnography in patients with two or more major sleep disturbance symptoms.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) is

characterised by repetitive, complete, or partial

collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep and, generally, reduction in oxygen desaturation.1 The

prevalence of OSAS is estimated to be 1% to 2% in

men and 1.2% to 2.5% in women.2 The prevalence

of OSAS in Turkey was reported as 1.8% in

epidemiological studies.3

Sleep-disordered diseases are associated with

a number of eye disorders including floppy eyelid

syndrome, optic neuropathy, keratoconus, retinal

vascular tortuosity and congestion, retinal bleeding,

non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

and papilloedema secondary to increased

intracranial pressure, normal tension glaucoma, and

primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).4 5 6 7 Sleep-disordered

breathing may impair autoregulation

of optic nerve perfusion due to the direct effect of

hypoxia. Glaucoma is a multifactorial and specific

optic neuropathy often characterised by increased

intra-ocular pressure (IOP) that results in typical

and progressive visual field loss.8

The prevalence of glaucoma in the general

population is between 1% and 2%.9 While the

aetiology of POAG still remains unclear, several

risk factors have been associated with the

condition. It was known that OSAS effects the

oxygenation, neurohumoral factors, and vascular

haemodynamics.4 It has been suggested that OSAS

aggravates or even causes glaucoma by impaired

optic nerve head blood flow and tissue atrophy,

infarction due to vascular dysregulation or by direct

damage to the optic nerve secondary to prolonged

hypoxia.4 9

In addition to elevated IOP, cardiovascular risk factors—such as arterial hypotension and

hypertension, vasospasms, autoregulatory defects,

and atherosclerosis—are of increasing importance

in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, especially in

normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Several recent

reports4 5 10 11 suggest that OSAS may be an

additional risk factor for glaucoma. Some of the

possible causes of glaucoma-like abnormal blood

coagulation, vasospastic disease, and optic nerve

vascular dysregulation are also consequences of

OSAS. It is not surprising, therefore, that some

studies4 5 10 11 show an increased prevalence of OSAS

in patients with glaucoma and vice versa. In clinical

practice, OSAS is often not taken into diagnostic

consideration in glaucoma patients.11

The association between glaucoma and OSAS

has been reported in many studies. Most of them

focused on the prevalence of glaucoma in OSAS

patients and indicated it as a risk factor. Some of

these articles have been observational case reports

or case series.4 12 13 14 15 The objective of this study was to

investigate the prevalence of OSAS in patients with

POAG.

Methods

Study group

This was a prospective case series that included 30

consecutive adult POAG patients who attended the

out-patient clinic of the Düzce University, School

of Medicine, Turkey between July 2007 and February 2008.

Informed consent was obtained from the study

participants.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals with diabetes mellitus (n=4), thyroid

function disorders (n=2), hyperlipidaemia (n=2),

and who refused to participate in the study (n=1)

were excluded.

Ophthalmological examination

All patients underwent routine eye examination,

including Snellen visual acuity, manifest refraction,

slit-lamp examination of the anterior eye segment,

IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and binocular

examination of the optic disc.

Patients were considered to have POAG if

they had untreated IOP of ≥21 mm Hg, an open

anterior chamber angle, glaucomatous visual field

defects or glaucomatous cupping of the optic disk,

and no fundus or neurological lesion other than

glaucomatous cupping to account for the visual field

defect.

Data collection

Prior to the sleep test, all POAG patients completed

a questionnaire about sleep disturbance. Data from the questionnaire were used to evaluate basic

OSAS symptoms such as snoring (presence of

snoring for at least five nights per week), witnessed

apnoea (spouse or relatives of patients with OSAS,

identifying noisy and irregular snoring, and arrested

respiration through the mouth and nose), and

daytime sleepiness. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale

was used to objectively evaluate excessive daytime

sleepiness. If the score obtained on this scale

was above 10, excessive daytime sleepiness was

considered present.16 All POAG patients received an

otorhinolaryngeal examination.

In addition, polysomnography (PSG; Somno-Medics Gmbh-8 Co. KG, Nonnengarten 8, D-97270

Kist Germany. Model: Somnoscreen-PSG, Ser-No:

0372 CAA5-OJ), electroencephalography, electro-oculography,

chin electromyography, oral and nasal

airflow (nasal-oral ‘thermistor’ and nasal cannula),

thorax movements, abdominal movements, arterial

oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry instrument),

electrocardiogram, and snoring recordings (>6

hours) were obtained from all patients. All records

were scored manually in a computer environment.

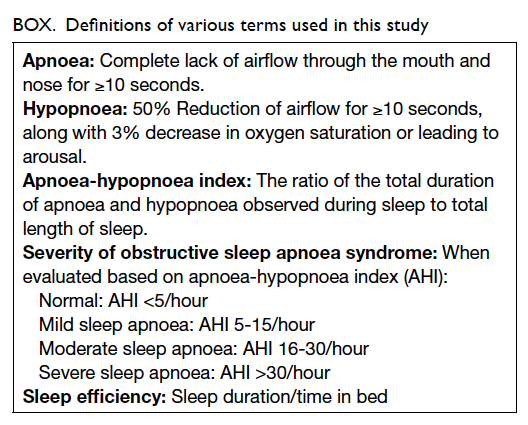

Definitions of various terms are shown in the Box.17

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for

the Social Sciences (Windows version 10.0; SPSS Inc,

Chicago [IL], US). Mann Whitney U test was used

for comparing quantitative data. Chi squared test or

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical

data. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically

significant. Spearman’s test was used for evaluating

correlations between sample pairs.

Results

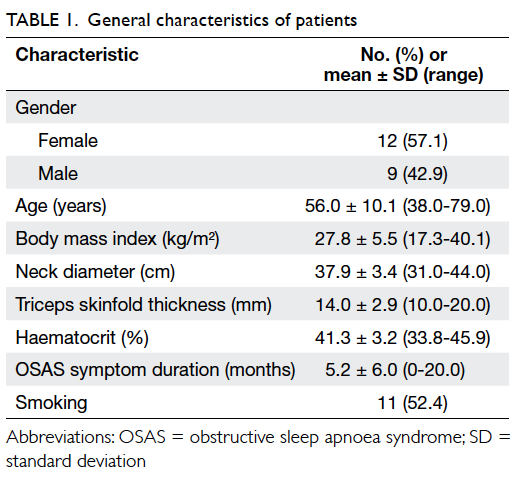

Of the 21 POAG patients, 12 were female and 9

were male. Demographic and clinical features of the

patients are summarised in Table 1.

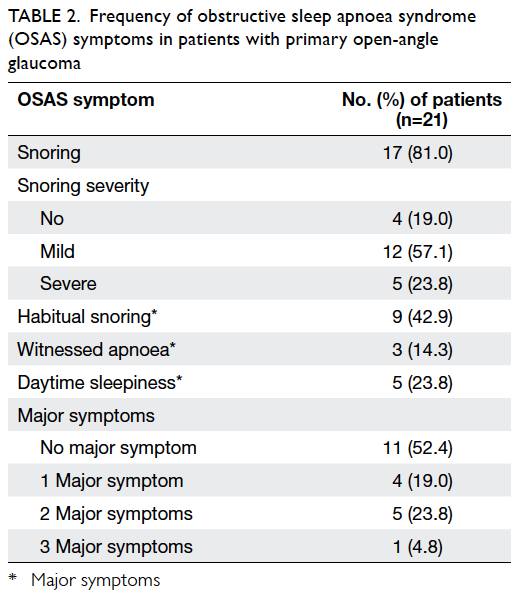

Snoring was the most prevalent (81.0%) major

symptom of OSAS; snoring was habitual in 42.9%

of the patients. Daytime sleepiness and witnessed

apnoea were found in 23.8% and 14.3% of the

patients, respectively. While no major symptom

was present in 52.4% of POAG patients, three major

symptoms were concomitantly present in one (4.8%)

POAG patient (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) symptoms in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma

Polysomnographic study showed that OSAS

was present in 33.3% (n=7) of the POAG patients

(apnoea-hypopnoea index [AHI] ≥5/hour). The

severity of OSAS was mild (AHI of 5-15/hour) in

14.3% (n=3) and moderate (AHI of 16-30/hour) in

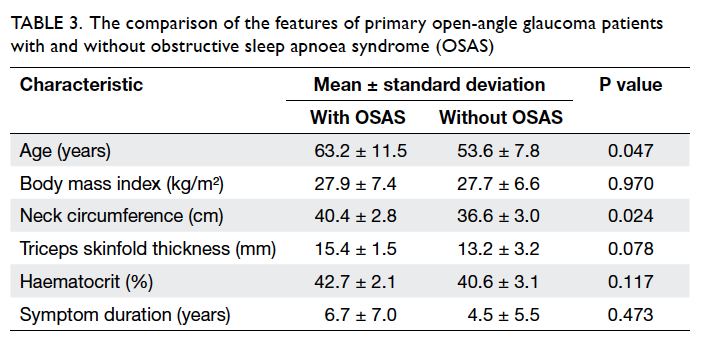

19.0% (n=4) of the patients. Age (P=0.047) and neck circumference (P=0.024) were significantly higher

in POAG patients with OSAS versus those without

OSAS; triceps skinfold thickness was also higher

in OSAS patients, but it did not reach statistical

significance (P=0.078). No significant difference

was observed between POAG patients with and without OSAS with regard to body mass index and

the duration of one or more major OSAS symptom

(Table 3).

Table 3. The comparison of the features of primary open-angle glaucoma patients with and without obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)

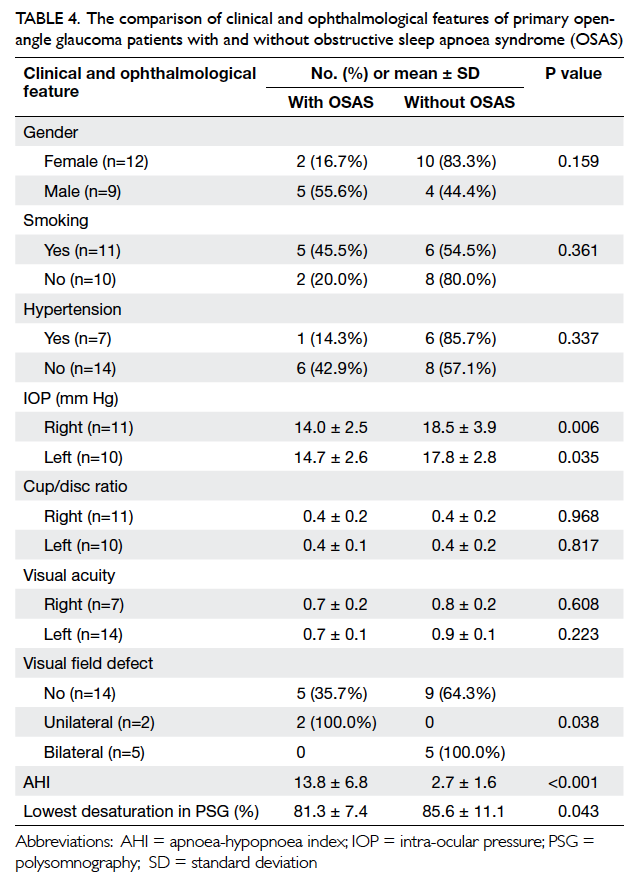

Primary open-angle glaucoma patients with

and without OSAS did not differ significantly in

terms of gender, smoking, hypertension, cup/disc

ratio, and visual acuity. Intra-ocular pressure in

POAG patients with OSAS was significantly lower

than that in patients without OSAS (P=0.006 and

P=0.035 for the right and left eyes, respectively).

Apnoea-hypopnoea index was significantly higher

(P<0.001) and the lowest desaturation on PSG was

significantly lower (P=0.043) in POAG patients with

OSAS than those without OSAS. Visual field defects

were significantly more common in POAG patients

with OSAS (P=0.038) [Table 4].

Table 4. The comparison of clinical and ophthalmological features of primary open-angle glaucoma patients with and without obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)

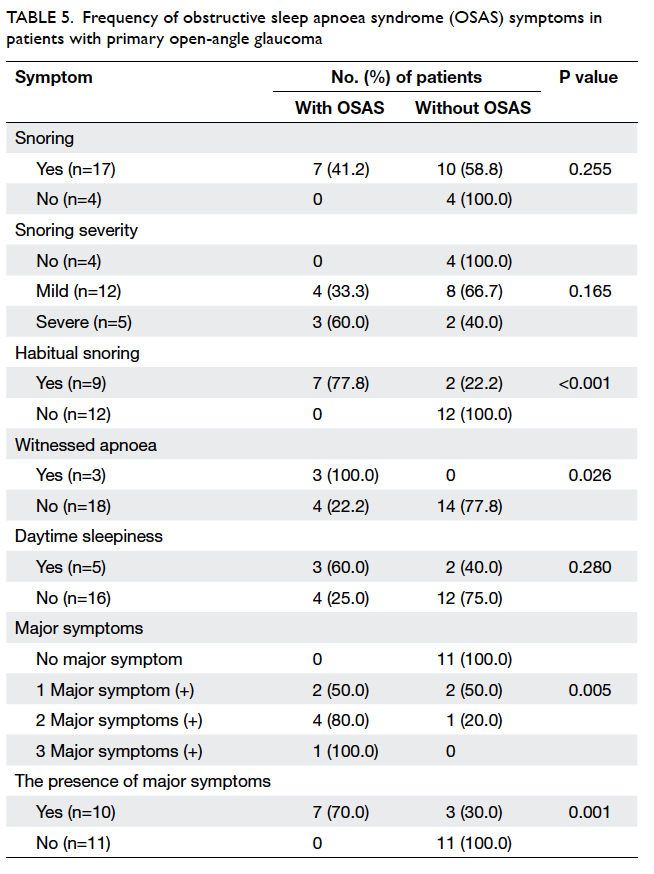

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome was

not observed in POAG patients with no snoring

(including simple snoring). As the degree of snoring

increased, OSAS prevalence reached almost

statistical significance. The symptoms of habitual

snoring (P<0.001) and witnessed apnoea (P=0.026)

were significantly more frequent in POAG patients

with OSAS versus those without OSAS (Table 5).

Table 5. Frequency of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) symptoms in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma

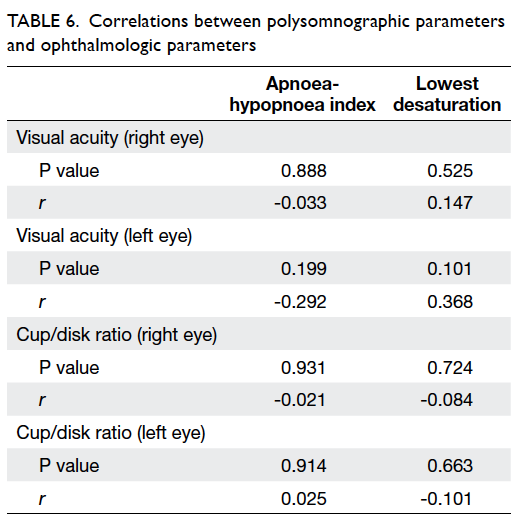

No correlation was detected between PSG

parameters (AHI, lowest desaturation in PSG) and

ophthalmologic parameters (cup/disc ratio, visual

acuity) in POAG patients (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of OSAS and the

associated symptoms were higher in POAG patients

than that in the general population.2 The prevalence

of OSAS of at least mild severity was even higher

compared with that in middle-aged adults (9% in

women and 24% in men).3 Intra-ocular pressure

levels in patients with OSAS were significantly lower

than in those without OSAS. Another important

finding of the present study was that there was a

statistically significant but clinically insignificant

difference between OSAS and non-OSAS patients

regarding visual field defect.

Vascular risk factors for POAG have

been hypothesised and researched. It has been

reported that potential cardiovascular risk factors

including systemic hypertension, atherosclerosis,

vasospasm, and acute hypotension are associated

with glaucoma.5 Nevertheless, some patients may

experience progression of their neuropathy even

though their IOP seems appropriately controlled.

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome could be

considered one of the risk factors for POAG. Since

glaucomatous optic neuropathy is multifactorial,

treatment of OSAS—which is currently a known and

modifiable risk factor—may help the control of IOP

and management of glaucoma.18

There are a few studies examining the

correlation between POAG and OSAS. A recent study19 determined the prevalence of OSAS in

POAG associated with snoring. Thirty-one snoring

glaucomatous patients prospectively underwent

PSG. Of these, 49% were diagnosed to have OSAS.19

Mojon et al4 performed overnight transcutaneous

finger oximetry in 30 consecutive patients having

POAG (mean age, 76.0 ± 7.9 years) and found that the

oximetry disturbance index (ODI) was significantly

higher (11%) in these patients compared with normal

controls of the same age and sex distribution. They

reported OSAS prevalence as 20% (n=6/30) in POAG

patients according to ODI.4 In a group of 16 NTG

patients, the OSAS prevalence was 50% in patients

aged 45 to 64 years, and 63% in patients older than

64 years.10 We found an OSAS prevalence of 33.3% in

POAG patients according to AHI.

Mojon et al5 reported a 7.2% prevalence of

NTG among 69 white patients with OSAS (mean

age, 52.6 ± 9.7 years), and it was significantly higher

than that expected in general white population (2%).5

In another study, Sergi et al20 found a 59% prevalence

of NTG in 51 OSAS patients (mean age, 64 ± 10

years). Contrary to the other studies, the prevalence

of glaucoma in a study involving 228 patients with

OSAS was reported to be the same as in the general

population.21

Age is a common risk factor of both OSAS and

POAG; the latter itself is an ageing-associated disease.

The incidence of OSAS in the general population has

been shown to be the highest between 45 and 65

years of age.22 Thus, high mean age (56.0 years) in

our study might have contributed to the observed high

prevalence of OSAS.

Snoring is known to be the most common

symptom in OSAS.23 A group of out-patients,

including those with POAG and without POAG,

was recruited for evaluation of sleep-disordered

breathing symptoms such as snoring, excessive

daytime sleepiness, and insomnia with the help of a

questionnaire.9 The authors reported high prevalence

of sleep-disordered breathing in POAG patients.

Compared with those without POAG, POAG patients

showed a higher prevalence of snoring (47.6% vs

38.0%), snoring plus excessive daytime sleepiness

(27.3% vs 17.3%), and snoring plus excessive

daytime sleepiness plus insomnia (14.6% vs 7.8%).9

The authors speculated that the large nocturnal

fluctuations in blood pressure of OSAS patients may

have interfered with normal ocular haemodynamics,

making the eye vulnerable to glaucoma.9 In the

logistic regression model, snoring was significantly

associated with glaucoma. However, that study was

not a follow-up study of glaucomatous patients

and snoring could not be accepted as a prognostic

factor of POAG.9 Moreover, their study did not use

objective measures such as overnight PSG for the

diagnosis; instead, they only relied on self-reported

symptoms.9 In another study,7 the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing symptoms was higher in

patients with NTG versus those without NTG (57%

vs 3%). However, contrary to our study, they only

offered PSG to patients with a positive sleep history.7

In our study, the prevalence rates of snoring, habitual snoring,

witnessed apnoea, excessive daytime sleepiness were

81.0%, 42.9%, 14.3%, and 23.8%, respectively. The concomitant presence of two or three

major OSAS symptoms was observed in 23.8% and

4.8% of our POAG patients, respectively. Blumen

Ohana et al19 reported high prevalence of OSAS in

patients with POAG and suggested that presence of

snoring should be explored at interview. Conversely,

patients who snore should be asked whether they

have POAG, and if so, should undergo all-night sleep

recording for the presence of OSAS.19 Mojon et al5

also found that respiratory disturbance index (RDI)

was positively correlated with IOP in 114 OSAS

patients. Because of the observational nature of that

study, they concluded only an association between

glaucoma and OSAS rather than a direct causal

relationship.5 A study by Karakucuk et al15 found that

the prevalence of glaucoma in patients with OSAS

was 12.9% (n=4/31); all these four patients with

glaucoma were in the severe OSAS group. There

was also a positive correlation between IOP and

AHI, and they suggested that increased IOP values

may reflect the severity of OSAS.15 In another cross-sectional

study, there was no correlation between

IOP and RDI.21 In the present study, IOP level in

patients with OSAS was significantly lower than that

in those without OSAS. Intra-ocular pressure shows

diurnal variation and patients with OSAS may have

elevated IOP and perfusional disturbance of retinal

nerve fibres during sleep. Therefore, these patients

may have completely normal or low IOP during the

daytime. On the other hand, most patients with

OSAS were regularly under glaucoma medication

which lowers the IOP to within normal limits.

Sergi et al20 did not find any difference in the

cup/disk ratio between the study patients and the

control group. They found a significant correlation

between AHI and the cup/disk ratio but none between

awake arterial blood gases and the ophthalmologic

examination data.20 They speculate that POAG could

be a consequence of changes in vascular tone and of

the increased platelet aggregability which frequently

occur in OSAS patients. In contrast with their study,

our study shows that the cup/disk ratio did not differ

between POAG patients with and without OSAS.

A study in Hong Kong24 examined the

computerised visual fields and optic discs of OSAS

patients with normal IOP and compared these with

non-OSAS population. Visual field indices were

significantly lower and the incidence of suspicious

glaucomatous disc changes was higher versus the

control arm.24 A variety of visual field defects in OSAS

patients were also reported by Mojon et al25 in nine patients; the field defects stabilised in two of these

after 18 months following continuous positive airway

pressure (CPAP). Kremmer et al11 have also reported

patients with NTG and progressive field loss despite

IOP-lowering eye drops and surgery. Nevertheless,

they stabilised field loss of patients after diagnosis

of OSAS and treatment with CPAP.11 Although there

was statistically significant difference in the visual

field defects of POAG patients with and without

OSAS in our study, it was clinically insignificant.

Only significant glaucomatous visual field defects

were considered in our evaluation. Therefore, minor

changes due to lenticular opacifications or other

aetiology were not taken into account as major

glaucomatous visual field changes.

Hypoxaemia and haemodynamic changes

resulting from intermittent apnoea and hypopnoea

during sleep are believed to play a role in

glaucomatous optic neuropathy.21 Although there is

no clear evidence for a cause-effect relationship in

the present study, the high prevalence of OSAS in

patients with POAG suggests a possible relationship.

Conclusions

In this study, the prevalence of OSAS was higher

in POAG patients versus the general population.

In clinical practice, OSAS is often not taken into

diagnostic consideration in glaucoma patients. The

high prevalence of OSAS in patients with POAG

suggests the need to explore the long-term results

of coincidence, relationship, and cross-interaction

between these two common disorders. Based on

data from the present study, we recommend that

the history of sleep apnoea symptoms be asked in

patients with glaucoma, especially in those who are

obese and have thick necks. In addition, PSG should

be performed in those patients with two or more

major sleep disturbance symptoms. Further large-scale studies are required to explore the

long-term results of these two common disorders, particularly in patients who

have been treated with CPAP therapy.

References

1. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults:

recommendations for syndrome definition and

measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report

of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force.

Sleep 1999;22:667-89.

2. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr

S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among

middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1230-5. CrossRef

3. Köktürk O. Epidemiology of sleep apnea syndrome. Tuberk

Toraks 1998;46:193-201.

4. Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, Böhnke M, Körner F,

Mathis J. Primary open-angle glaucoma is associated with

sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmologica 2000;214:115-8. CrossRef

5. Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, et al. High prevalence

of glaucoma in patients with sleep apnea syndrome.

Ophthalmology 1999;106:1009-12. CrossRef

6. McNab AA. The eye and sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev

2007;11:269-76. CrossRef

7. Marcus DM, Costarides AP, Gokhale P, et al. Sleep

disorders: a risk factor for normal-tension glaucoma? J

Glaucoma 2001;10:177-83. CrossRef

8. Dhillon S, Shapiro CM, Flanagan J. Sleep-disordered

breathing and effects on ocular health. Can J Ophthalmol

2007;42:238-43. CrossRef

9. Onen SH, Mouriaux F, Berramdane L, Dascotte JC,

Kulik JF, Rouland JF. High prevalence of sleep-disordered

breathing in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma.

Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000;78:638-41. CrossRef

10. Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, et al. Normal-tension

glaucoma is associated with sleep apnea syndrome.

Ophthalmologica 2002;216:180-4. CrossRef

11. Kremmer S, Selbach JM, Ayertey HD, Steuhl KP. Normal

tension glaucoma, sleep apnea syndrome and nasal

continuous positive airway pressure therapy—case report

with a review of literature [in German]. Klin Monbl

Augenheilkd 2001;218:263-8.

12. Grieshaber MC, Flammer J. Blood flow in glaucoma. Curr

Opin Ophthalmol 2005;16:79-83. CrossRef

13. Grieshaber MC, Mozaffarieh M, Flammer J. What is the

link between vascular dysregulation and glaucoma? Surv

Ophthalmol 2007;52 Suppl 2:S144-54.

CrossRef

14. Hayreh SS. The 1994 Von Sallman Lecture. The optic

nerve head circulation in health and disease. Exp Eye Res

1995;61:259-72. CrossRef

15. Karakucuk S, Goktas S, Aksu M, et al. Ocular blood flow

in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).

Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;246:129-34. CrossRef

16. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime

sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540-5.

17. International classification of sleep disorders, version 2:

diagnostic and coding manual. Rochester, MN: American

Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

18. Blumen-Ohana E, Blumen M, Aptel F, Nordmann JP.

Glaucoma and sleep apnea syndrome [in French]. J Fr

Ophtalmol 2011;34:396-9. CrossRef

19. Blumen Ohana E, Blumen MB, Bluwol E, Derri M, Chabolle

F, Nordmann JP. Primary open angle glaucoma and

snoring: prevalence of OSAS. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol

Head Neck Dis 2010;127:159-64. CrossRef

20. Sergi M, Salerno DE, Rizzi M, et al. Prevalence of normal

tension glaucoma in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

patients. J Glaucoma 2007;16:42-6. CrossRef

21. Geyer O, Cohen N, Segev E, et al. The prevalence of

glaucoma in patients with sleep apnea syndrome: same as in

the general population. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:1093-6. CrossRef

22. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A.

Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and

severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:144-8. CrossRef

23. Köktürk O. The clinical features of OSAS. Tuberk Toraks

1999;47:117-26.

24.

Tsang CS, Chong SL, Ho CK, Li MF. Moderate to severe

obstructive sleep apnoea patients is associated with a higher

incidence of visual field defect. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:38-42. CrossRef

25.

Mojon DS, Mathis J, Zulauf M, Koerner F, Hess CW.

Optic neuropathy associated with sleep apnea syndrome.

Ophthalmology 1998;105:874-7. CrossRef