Hong Kong Med J 2014 Aug;20(4):350.e3–4

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134046

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Diffuse xanthomatous eruption

HF Cheng, MB, BS, MRCP (UK); William YM Tang, FRCP (Edin), FHKAM (Medicine); KC Lee, FRACPath, FHKAM (Pathology)

DERM 1 Skin Specialists Centre, Room 1102, Champion Building,

301-309 Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr HF Cheng (chf@doctor.com)

A 37-year-old non-smoker with no history of drug

allergy and history of childhood asthma presented

with itchy rash over his back for 1 month, which

progressed to involve his limbs and both axillae,

in January 2013. The patient was not taking any

medication apart from health supplements. He did

not have any complaints of joint pain or fever. He was

seen by a general practitioner who managed the rash

as viral infection. Family history of hyperlipidaemia

was negative. On examination, the patient was an

obese man with body mass index of 32 kg/m2, blood

pressure of 152/89 mm Hg, and pulse rate of 100

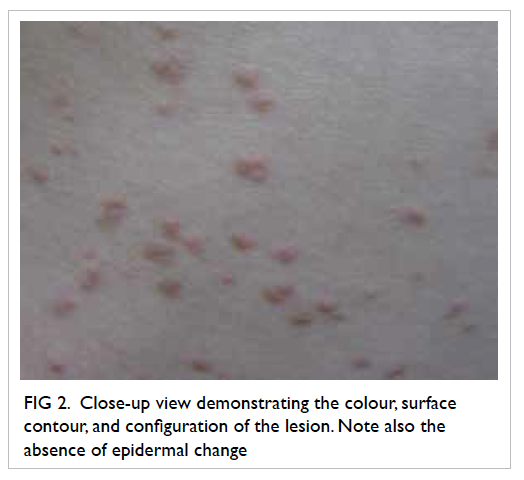

beats/min. There were widespread, reddish-yellow

papular eruptions over both sides of the trunk and

limbs, sparing the face, scalp, oral cavity, and ears

(Fig 1). There were no scales, vesicles, pus formation,

or erosions. The size of the lesions ranged from to

0.1 cm to 0.4 cm (Fig 2). There was no corneal arcus,

regional lymphadenopathy, abdominal organomegaly

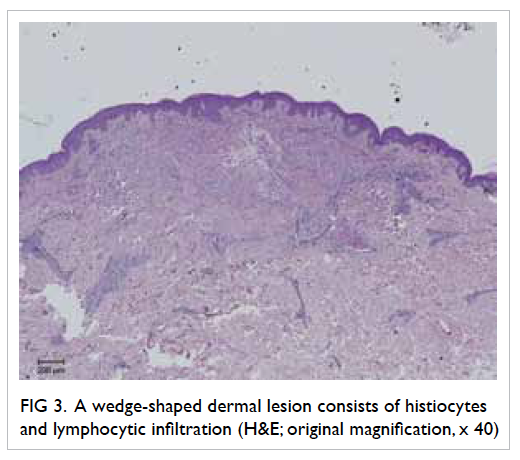

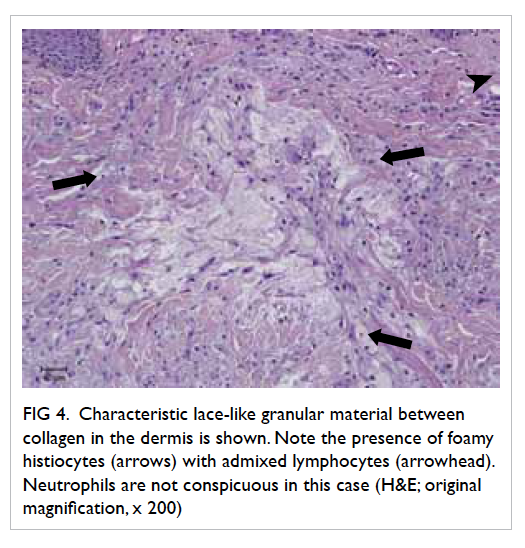

or arthropathy. A skin biopsy of the lesion showed

features of eruptive xanthoma (Figs 3 and 4). Fasting

blood examination showed markedly elevated levels

of total cholesterol (12.1 mmol/L), serum triglycerides (40.36 mmol/L), and plasma glucose (14.7 mmol/L).

Thus, he was urgently referred to an endocrinologist.

Figure 2. Close-up view demonstrating the colour, surface contour, and configuration of the lesion. Note also the absence of epidermal change

Figure 3. A wedge-shaped dermal lesion consists of histiocytes and lymphocytic infiltration (H&E; original magnification, x 40)

Figure 4. Characteristic lace-like granular material between collagen in the dermis is shown. Note the presence of foamy histiocytes (arrows) with admixed lymphocytes (arrowhead). Neutrophils are not conspicuous in this case (H&E; original magnification, x 200)

Discussion

Eruptive xanthoma is a benign lesion and patients

usually consult because of itchiness or for

cosmetic reasons. Morbidity arises from metabolic

complications such as acute pancreatitis or myocardial

infarction. The macroscopic lesions arise from

phagocytosis in the dermis of plasma lipoproteins

that leak from capillaries.1 Laboratory workup is

mandatory to exclude diabetes, nephrotic syndrome,

or hypothyroidism. Screening of family members is essential as genetic factors may contribute in the

development of the condition.2 Eruptive xanthoma

can occur in individuals with normal lipid levels.3

Under these circumstances, it is prudent to exclude

occult malignancy (eg lymphoproliferative disorders

and monoclonal paraproteinaemia) or infections (eg

human immunodeficiency virus infection).4 Solitary

lesions necessitate enquiry about previous local

trauma, dermatoses, or surgical operation for Köbner

phenomenon might have happened.

Differential diagnoses include eruptive

xanthogranuloma, xanthoma disseminatum,

and Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Xanthogranuloma usually arises in the head-and-neck

regions of children. It is mostly a solitary,

small-sized papule or nodule. Ophthalmologic

evaluation is indicated if ocular involvement is

suspected. Histopathology shows collection of

lipidised histiocytes, inflammatory infiltrates, and

Touton giant cells in the dermis. Known as non-LCH, xanthoma disseminatum is a non-familial

histiocytic disorder. Mucocutaneous as well as

systemic involvement has been reported. It shares

similar histopathological features with eruptive

xanthogranuloma but eosinophils may be absent, and

Touton giant cells may be inconspicuous. Treatment, by far, is unsatisfactory. Langerhans cell histiocytosis

comprises a spectrum of disorders with varied clinical

manifestations including cutaneous involvement.

Confirmation of diagnosis rests on histopathology.

Within the lesion is dense infiltration by abnormal

Langerhans cells which are characterised by their

folded nuclei. Presence of a mixed inflammatory

infiltrate with eosinophils in the background forms

the classical picture of LCH. The Langerhans cells

in LCH differ from the typical Langerhans cells by

the lack of dendritic cell processes, and this feature

is best demonstrated by CD1a immunostaining. All

these differential diagnoses lack the characteristic

deposits of lace-like material between collagen seen

in eruptive xanthoma.

Gradual resolution of the cutaneous lesions is

usually expected upon normalisation of lipid level in

patients with eruptive xanthoma. En-bloc surgical

excision or carbon dioxide laser vaporisation is equally

practical, depending on the extent of the disease. The

use of carbon dioxide laser has been reported in a skin

phototype VI patient with xanthoma disseminatum

with cosmetically acceptable post-inflammatory

hyperpigmentation.5 Finally, referral to a physician

is needed in patients with concomitant metabolic

syndrome.

References

1. Massengale WT, Nesbitt LT Jr. Xanthomas. In: Bolognia

JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd

ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2008: 1411-9.

2. Pickens S, Farber G, Mosadegh M. Eruptive xanthoma: a

case report. Cutis 2012;89:141-4.

3. Williford PM, White WL, Jorizzo JL, Greer K. The

spectrum of normolipemic plane xanthoma. Am J

Dermatopathol 1993;15:572-5. CrossRef

4. Ramsay HM, Garraido MC, Smith AG. Normolipaemic

xanthomas in association with human immunodeficiency

virus infection. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:571-3. CrossRef

5. Carpo BG, Grevelink SV, Brady S, Gellis S, Grevelink JM.

Treatment of cutaneous lesions of xanthoma disseminatum

with a CO2 laser. Dermatol Surg 1999;25:751-4. CrossRef