Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:121–5 | Number 2, April 2014 | Epub 7 Oct 2013

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133988

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lower extremity lymphedema: local experience

MC Lam, MB, ChB; WH Luk, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology); KH Tse, MB, ChB

Department of Radiology and Organ Imaging, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MC Lam (karrylam1121@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To review our local experience in the use

of lymphoscintigraphy to evaluate lymphedema of

the lower extremities.

Design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: A local regional hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: Images and records of all patients

presenting to our hospital with suspected lower

limb lymphedema from 1998 to 2011 for whom

lymphoscintigraphy was performed were reviewed.

Main outcome measures: Lymphoscintigraphy

findings and clinical outcomes.

Results: In all, 24 patients (13 males and 11

females; age range, 14-83 years) had undergone

lymphoscintigraphy for suspected lower limb

lymphedema. Eight cases were confirmed positive, including one with lymphangiectasia, five with

lymphatic obstruction, and two with lymphatic

leakage. No complication was encountered.

Conclusion: Lymphoscintigraphy is safe and

effective for the evaluation of lymphedema in lower

extremities.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Our local experience confirmed the diagnostic value of lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphedema of lower extremities.

- Prompt diagnosis of lymphedema is crucial as effective treatment may be available. Lymphoscintigraphy aids the diagnosis of lymphedema, identification of causes and the approximate site of lymphatic obstruction, and should therefore be considered under appropriate clinical settings.

Introduction

Lymphedema is the accumulation of tissue fluid in

the interstitial spaces, resulting from anatomical

or functional lymphatic obstruction or defective

lymphatic drainage.1 Local data about the

prevalence of this condition are not available, but

it is estimated to affect 2 to 3 million inhabitants

in the US.2 Lymphoscintigraphy has emerged and

become the standard investigation in the evaluation

of lymphedematous extremities. We reviewed our

experience in the use of lymphoscintigraphy for this

purpose in a single regional hospital.

Methods

We retrospectively identified all the cases with

suspected lower limb lymphedema referred for

lymphoscintigraphy from 1998 to 2011. Case records

and imaging studies were reviewed.

Imaging techniques

Studies conducted from 1998 to 2007 were performed

with a single detector system (Picker Prism 1000; Picker International, Cleveland [OH], US). Studies

performed after 2007 were performed with a single

photon emission computed tomography–computed

tomography imaging system (Siemens Symbia T6;

TruePoint SPECT CT, Siemens Medical Solutions,

Illinois, US). The interdigital web space between the

first and second digits on the patient’s lower limbs

was anaesthetised with local anaesthetic cream,

and subsequently 0.5 mCi of Technetium-99m

filtered sulphur colloid (through 0.22 micron filter)

was injected into the preanaesthetised interdigital

web spaces, creating a wheal. About 1 to 2 minutes

after the injection, patients were encouraged to

exercise their toes. Two-phase dynamic images were

obtained at 5 minutes (from toes to knee) and 10

minutes (from knee to groin). Anterior whole-body

scans were obtained at 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes.

Delayed 4-hour and 24-hour whole-body scans were

obtained whenever deemed necessary.

Results

There were 24 patients with suspected lymphedema

of lower extremities who had undergone lymphoscintigraphy. The patients were aged 14 to 83

(mean, 58) years; 13 were males and 11 were females.

Apart from mild pain during injection, all patients

tolerated the examination well without any serious

complication.

Lymphoscintigraphy findings

A predictable sequence should be seen in patients

with normal lymphatic anatomy and function. In the

lower limb, there should be symmetrical migration

of radionuclide through discrete lymph vessels (3-5 per calf and 1-2 per thigh). Ilioinguinal nodes should

be visualised within 1 hour. Typically, 1 to 3 popliteal

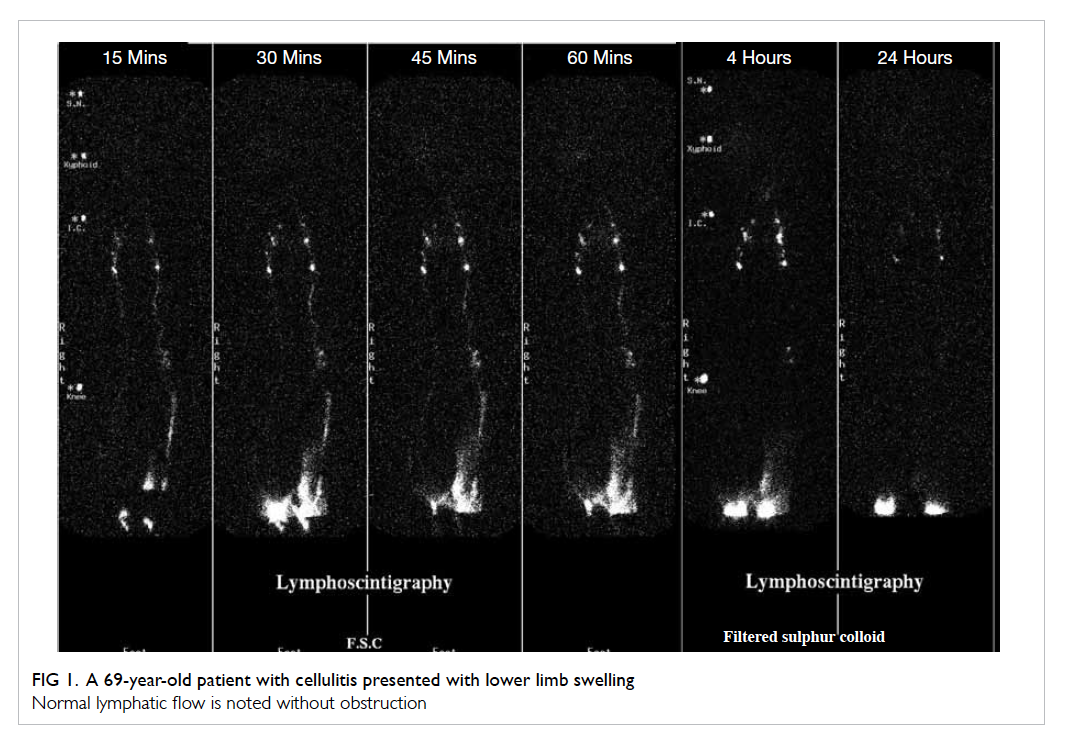

nodes and 2 to 10 ilioinguinal nodes are seen. Figure 1 shows a normal lymphoscintigraphic examination

of the lower limbs.

Abnormal lymphoscintigraphy scans manifest

a wide range of findings, including interruption of

lymphatic flow, collateral lymph vessels, dermal

backflow, reduced number of lymph nodes, dilated

lymphatics, delayed or non-visualisation of lymph

nodes and even the lymphatic systems.

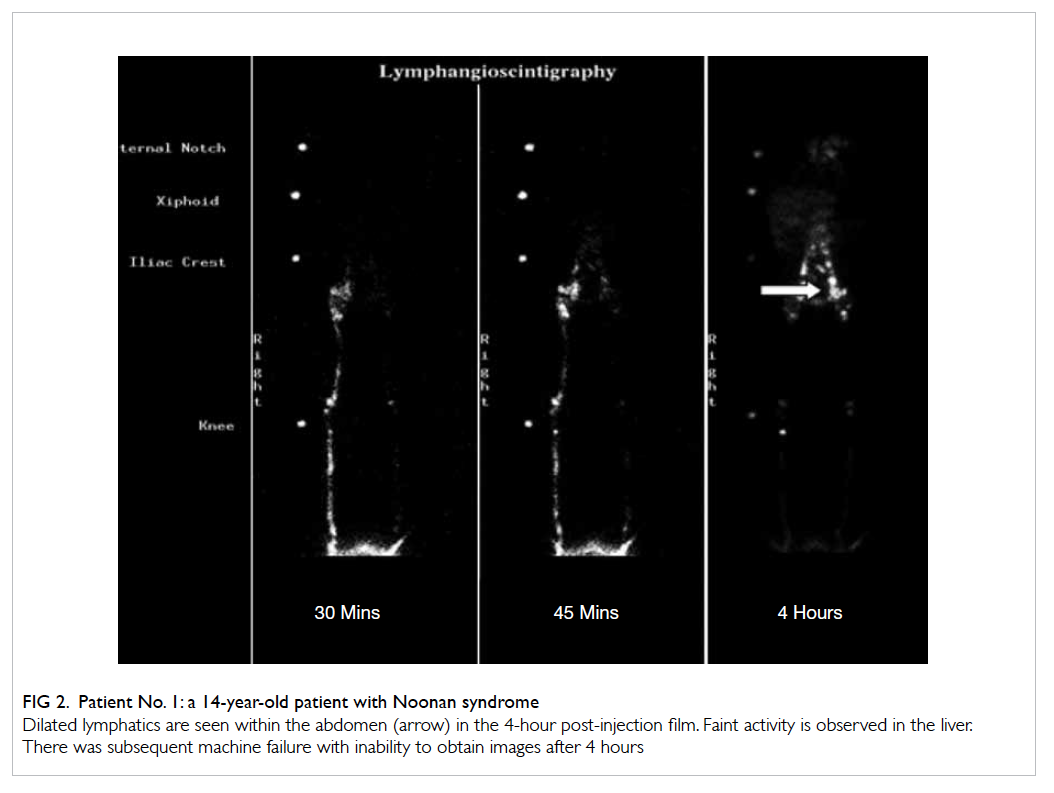

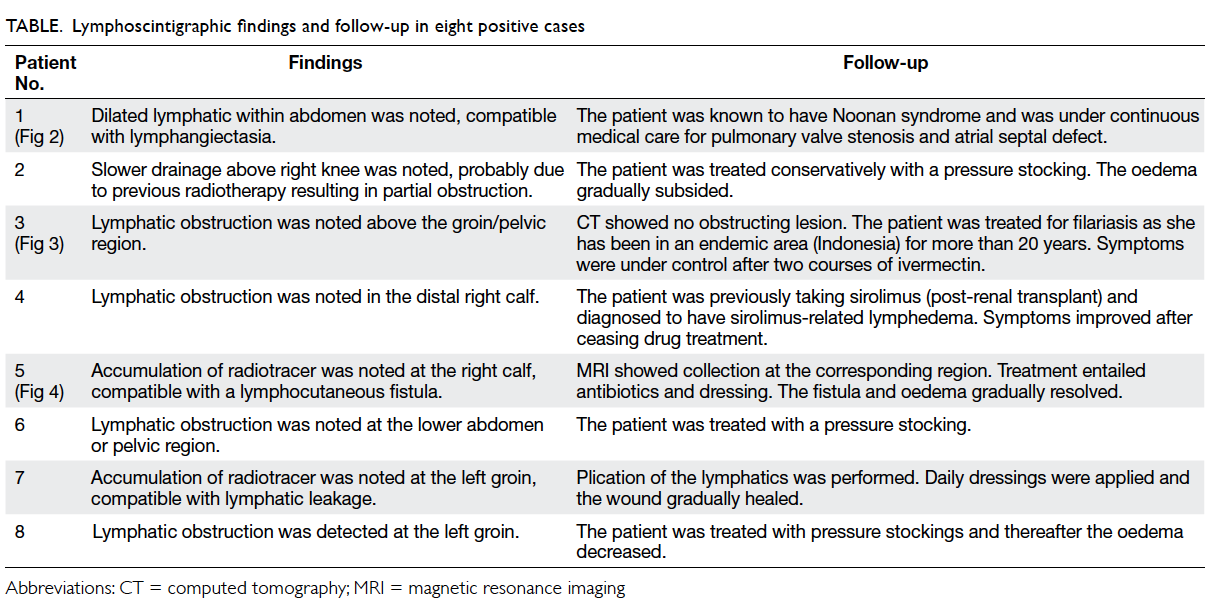

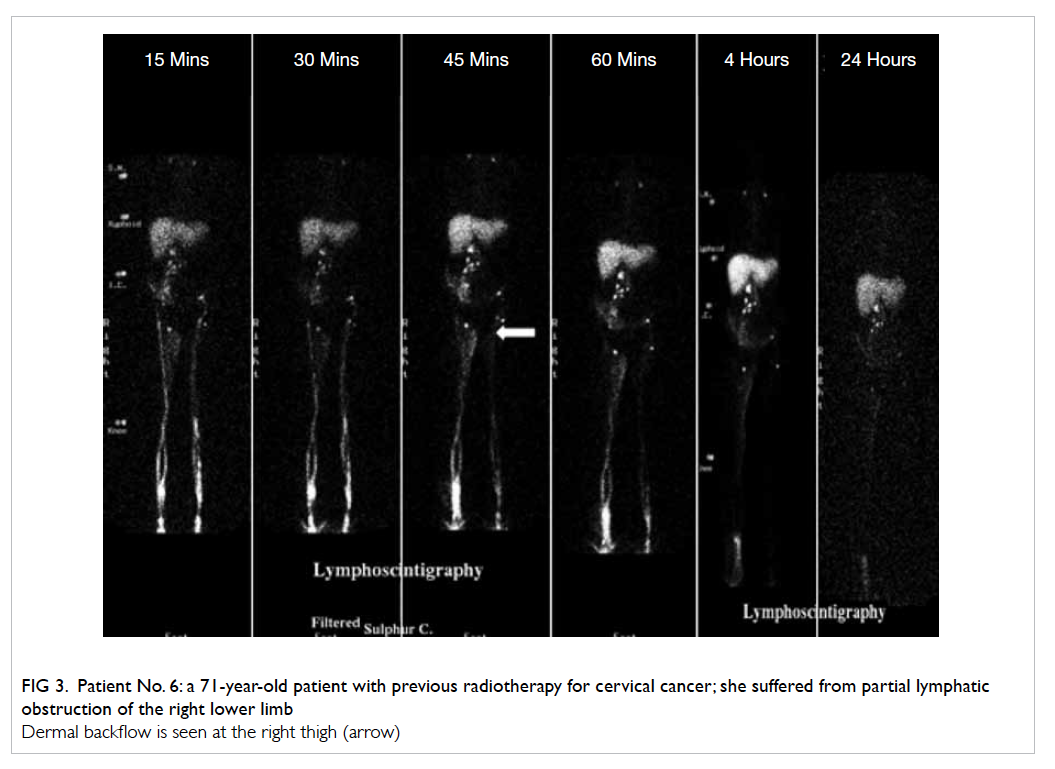

There were eight patients confirmed to be

positive for lymphedema. These included one

with lymphangiectasia (Fig 2), five with lymphatic

obstruction (Fig 3), and two with lymphatic

leakage (Fig 4). The Table summarises the

lymphoscintigraphic findings and follow-up data on

these eight cases.

Figure 3. Patient No. 6: a 71-year-old patient with previous radiotherapy for cervical cancer; she suffered from partial lymphatic obstruction of the right lower limb

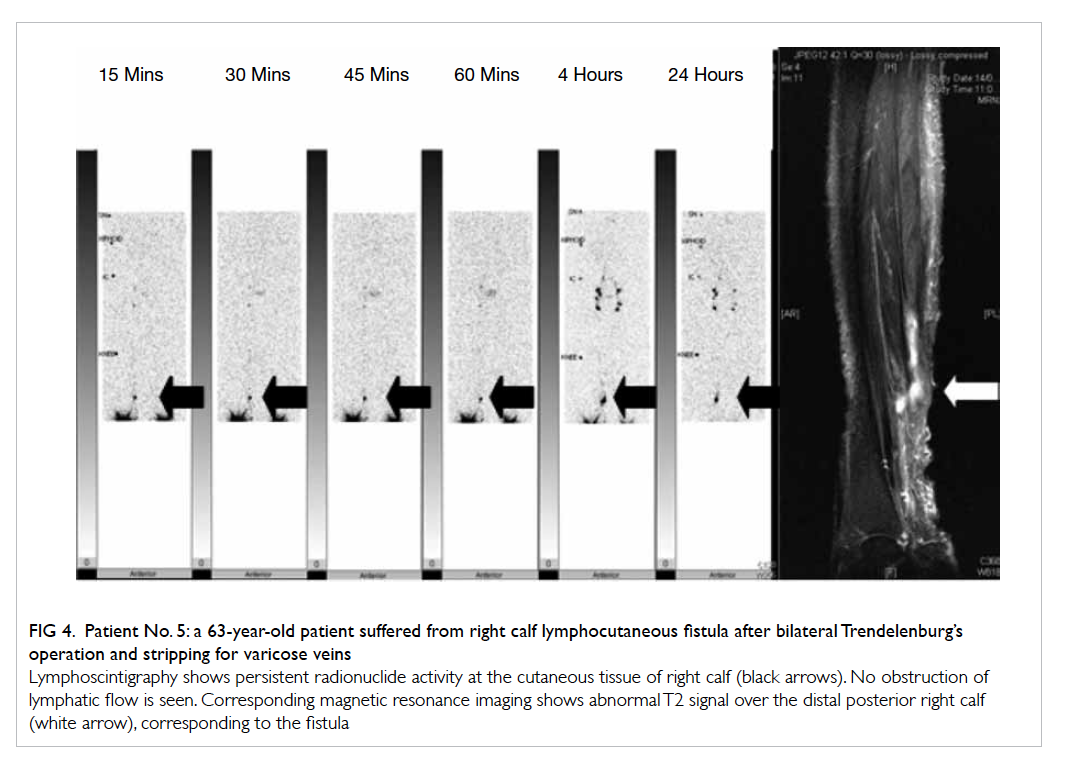

Figure 4. Patient No. 5: a 63-year-old patient suffered from right calf lymphocutaneous fistula after bilateral Trendelenburg’s operation and stripping for varicose veins

Discussion

Lymphedema of the extremities is typically a chronic

disease, which is often misdiagnosed and results in

significant functional impairment, and may give rise

to reduced coordination and mobility.3 Therefore,

prompt and accurate diagnosis of the condition is

important.

Decades ago, lymphangiography had been

used to investigate lymphatic disorders, but it

was a time-consuming investigation involving

direct cannulation of lymph vessels. Moreover, complications such as infections, hypersensitivity,

oil embolism, and lymphatic obstruction were

reported.4 Lymphoscintigraphy has replaced

lymphangiography and become the investigation of

choice. Its advantages include being non-invasive, free from adverse effects, and low radiation exposure

to patients. Furthermore, it can be repeated and

can even be used to follow-up after treatment

response.5 The reported sensitivity and specificity of

lymphoscintigraphy is approximately 66 to 100% and 83.5 to 99%, respectively.6

Lymphedema can usually be diagnosed

clinically. The differential diagnosis of suspected

lower-extremity lymphedema includes obesity,

chronic venous insufficiency, Milroy’s disease,7

and systemic diseases (eg hypoalbuminaemia).

Lymphoscintigraphy enables confirmation of the

diagnosis in unclear cases, assessing the risk of

developing lymphedema,8 predicting the outcome of

therapy,9 and assessing the results of lymphedema

treatment.10 11 12 13

Lymphoscintigraphy can usually identify

the approximate anatomical site of lymphatic

obstruction adequately. However, when greater

anatomical details are warranted, cross-sectional

imaging techniques like computed tomography

and magnetic resonance imaging can be used to

supplement the findings.14 This point was well

illustrated in this study.

Lymphoscintigraphy aids the diagnosis of

underlying lymphatic disorders and hence, guides

subsequent treatment, which have proven to be

effective in the management of lymphedema.15 16 17 18 19

Conservative treatment includes physical therapy,

drug therapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation.14

Operative treatment includes microsurgery,

liposuction, and surgical resection.14 The treatment

choice depends on the cause of lymphedema, disease

severity, functional impairment, and availability of

local expertise.

Conclusion

Lymphoscintigraphy is a safe and effective

investigation for suspected lymphatic disorders. Our

local experience supports its use in the investigation

of lower-extremity lymphedema in our locality.

References

1. Ter SE, Alavi A, Kim CK, Merli G. Lymphoscintigraphy. A reliable test for the diagnosis of lymphedema. Clin Nucl Med 1993;18:646-54. CrossRef

2. Rockson SG, Rivera KK. Estimating the population burden of lymphedema. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1131:147-54. CrossRef

3. Szuba A, Shin WS, Strauss HW, Rockson S. The third circulation: radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphedema. J Nucl Med 2003;44:43-57.

4. Van Rensburgl. Lymphangiography—its technique and value. S Afr Med J 1965;39:271-7.

5. Williams WH, Witte CL, Witte MH, McNeill GC. Radionuclide lymphangioscintigraphy in the evaluation of peripheral lymphedema. Clin Nucl Med 2000;25:451-64. CrossRef

6. Bourgeois P. Critical analysis of the literature on lymphoscintigraphic investigations of limb edemas. Eur J Lymphology Relat Probl 1996;6:1-9.

7. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, Odom RB, editors. Andrews' diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006: 849.

8. Bourgeois P, Leduc O, Leduc A. Imaging in the management and prevention of posttherapeutic upper limb edema. Cancer 1998;83(12 Suppl American):2805-13.

9. Szuba A, Strauss W, Sirsikar SP, Rockson SG. Quantitative radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy predicts outcome of manual lymphatic therapy in breast cancer–related lymphedema of the upper extremity. Nucl Med Commun 2002;23:1171-5. CrossRef

10. Campisi C. Lymphoedema: modern diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Int Angiol 1999;18:14-24.

11. Ho LC, Lai MF, Yeates M, Fernandez V. Microlymphatic bypass in obstructive lymphedema. Br J Plast Surg 1988;41:475-84. CrossRef

12. Brorson H, Svensson H, Norrgren K, Thorsson O. Liposuction reduces arm lymphedema without significantly altering the already impaired lymph transport. Lymphology 1998;31:156-72.

13. Hwang JH, Kwon JY, Lee KW, et al. Changes in lymphatic function after complex physical therapy for lymphedema. Lymphology 1999;32:15-21.

14. International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema. 2009 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2009;42:51-60.

15. McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Yurick JL, Dayes IS, Mackey JR. Conservative and dietary interventions for cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 2011;117:1136-48. CrossRef

16. Badger CM, Peacock JL, Mortimer PS. A randomized, controlled, parallel-group clinical trial comparing multilayer bandaging followed by hosiery versus hosiery alone in the treatment of patients with lymphedema of the limb. Cancer 2000;88:2832-7. CrossRef

17. Miller TA, Wyatt LE, Rudkin GH. Staged skin and subcutaneous excision for lymphedema: a favorable report of long-term results. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:1486-98; discussion 1499-501. CrossRef

18. Yamamoto Y, Sugihara T. Microsurgical lymphaticovenous implantation for treatment of chronic lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101:157-61. CrossRef

19. Matarasso A, Hutchinson OH. Liposuction. JAMA 2001;285:266-8. CrossRef