Hong Kong Med J 2025 Apr;31(2):130–8 | Epub 9 Apr 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Migrant workers’ well-being after the rampant

sweep of the Omicron wave in Hong Kong

Kitty KY Lai, BSc1; Hong Qiu, BSc, PhD1,2; Eliza LY Wong, MPH, PhD1,2

1 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Centre for Health Systems and Policy Research, The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Eliza LY Wong (lywong@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The impact of the coronavirus disease

2019 pandemic has rendered migrant workers a

vulnerable population susceptible to psychological

distress. This cross-sectional study aimed to estimate

the prevalence of anxiety and examine associations

of perceived social support and working conditions

with anxiety among Filipina domestic workers

(FDWs) after the peak of the Omicron wave in Hong

Kong.

Methods: In total, 370 female FDWs were recruited

through convenience sampling in Central, Hong

Kong, during holiday gatherings from June to August

2022; social normalcy had begun to return during

this period after the peak of the Omicron pandemic.

Anxiety levels were assessed using the Generalised

Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale. Perceived social

support and working conditions were measured

using validated instruments. Socio-demographic

characteristics and health-related information were

recorded for consideration as covariates.

Results: The estimated prevalence of anxiety

(GAD-7 score ≥10) was 8.6% (95% confidence

interval [CI]=5.8%-11.5%). Multivariable logistic

regression demonstrated that greater satisfaction

with compensation and salary (adjusted odds ratio

[aOR]=0.825, 95% CI=0.728-0.935), increased free time and rest periods (aOR=0.878, 95% CI=0.780-0.987), and higher satisfaction with value orientation

(aOR=0.887, 95% CI=0.796-0.989) were associated

with lower anxiety risk.

Conclusion: Migrant workers constitute a vital

workforce but are often neglected in preventive care.

Based on these findings, preventive measures such

as labour protection, compensation for overtime

work, adequate rest periods, and improved working

conditions are crucial in mitigating anxiety. This

study highlights key areas for policy refinement and

governmental support to enhance migrant workers’

well-being.

New knowledge added by this study

- Overall, 8.6% of Filipina domestic workers (FDWs) experienced probable anxiety after the Omicron wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Hong Kong.

- Associations between anxiety and working conditions were identified, indicating potential factors that influence the mental well-being of FDWs.

- No significant association was observed between anxiety and perceived social support.

- The Hong Kong government could prioritise refining policies to support favourable working conditions for migrant workers, including negotiation of an increase in meal allowances and strict enforcement of regular working hours.

- Non-governmental organisations could tailor psychological interventions to migrant workers to address diverse mental health needs.

Introduction

Declared a public health emergency of international

concern by the World Health Organization,

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has

continuously posed a threat to both physical and

psychological health.1 Beginning in December 2021,

the Omicron variant triggered the fifth wave of the

pandemic in Hong Kong, endangering psychological well-being.1 2 Filipina domestic workers (FDWs),

the primary group of migrant domestic workers,

constitute >2.5% of the Hong Kong population3

and are considered a vulnerable population. Before

the Hong Kong government reiterated the rights of

migrant workers, many FDWs faced mistreatment,

including abuse, exploitation, and illegal dismissal

upon infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).4 5 6 Filipina

domestic workers were susceptible to both direct and

indirect consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Migrant workers often experience poor

psychosocial conditions and substandard working

environments.4 5 6 7 8 However, few studies have

consistently examined the well-being of FDWs.8 9 10

Anxiety, a key indicator of well-being, commonly

coexists with other psychological conditions.

Considering the large number of domestic workers

in Hong Kong, efforts to safeguard the psychological

health of this minority population are essential to

prevent excessive strain on the healthcare system.11

Additionally, various aspects of working conditions

should be investigated in relation to anxiety.12

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of

anxiety and examine its relationships with perceived

social support and decent work among FDWs after

the peak of the Omicron wave during the COVID-19

pandemic in Hong Kong. Insights regarding the

psychosocial conditions encountered by FDWs

during the aftermath of the pandemic may contribute

to existing literature.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey, written in English, was

administered between June and August 2022. The

target population comprised FDWs. Eligibility

criteria included age ≥18 years, ability to read and understand English, and ability to provide informed

consent. Filipina domestic workers who began

employment on or after 1 February 2022 in Hong

Kong, as well as male FDWs, were excluded from

the present study. Because the majority of FDWs are

women (97.8%), the inclusion of a small sample of

male FDWs could compromise representativeness.3

Convenience sampling was utilised.

Recruitment was conducted at gathering places

in Central, Hong Kong, where a large proportion

of FDWs spend their days off. Data collection was

performed on rest days (Sundays and statutory

holidays). Support and clarifications were provided

to respondents who required assistance in

understanding the questions. Respondents were

offered a gratuity of HK$20 in cash as a token

of appreciation for their time and assistance.

According to Yeung et al,10 the prevalence of anxiety

among FDWs in Hong Kong at the beginning of the

pandemic was 25%. With a 95% confidence interval

(95% CI) and a desired margin of error of ±5%, the

minimum required sample size was estimated to be

289.

Data collection tool and measurement

The questionnaire consisted of four sections,

namely, anxiety, perceived social support, working

conditions, and potential covariates (eg, socio-demographic

and health-related factors). The

questionnaire was developed based on validated

instruments and a literature review of similar

contexts.12 13 14 15 16 17

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

scale was adopted to assess anxiety levels.13 The

total score ranges from 0 to 21; a threshold score

of ≥10 to identify self-reported anxiety provides

optimal sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%).13 The

GAD-7 has demonstrated high internal consistency

in the general population (Cronbach’s alpha=0.92)

and among FDWs working in Chinese regions

(Cronbach’s alpha=0.80).18 19

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived

Social Support, using a 7-point Likert scale, was

used to measure perceived social support across

three domains, namely, significant others, family,

and peers.14 Each domain comprises four items. We

calculated a mean score for each domain ranging

from 1 to 7 and a total mean score averaged from the

three concerned domains to represent the total score

of perceived social support. A higher score indicates

a greater level of perceived social support. The

authors of the scale proposed multiple approaches

for interpreting perceived social support, one of

which involved analysing continuous data for the

three domains and the overall score.14 This scale has

been validated with high internal consistency among

Southeast Asian domestic workers in Hong Kong

(Cronbach’s alpha=0.96).16 20

The Decent Work Scale was adopted to

evaluate working conditions, including 15 items

grouped into five components, namely, physically

and interpersonally safe working conditions, access

to essential healthcare support, sufficient income,

adequate rest time, and alignment of working

settings with social values.12 Each item scored from

1 to 7, resulting in component scores ranging from 3

to 21 and a total score ranging from 15 to 105, with

higher scores indicating better working conditions.

This scale has been validated with high internal

consistency among the working population in the

US (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86).12

Data analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

(Windows version 27.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

US). Confidence intervals were established at the

95% level, and P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant. We computed 95% CIs for

anxiety prevalence. Socio-demographic variables

were compared between anxiety statuses using the

Chi squared test, whereas scores for perceived social

support and working conditions were compared

using the independent samples t test.

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were computed

using a binary logistic regression model. For

univariable analysis, simple logistic regression was

conducted; perceived social support and working

conditions constituted the main independent

variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis

was performed to estimate the independent effects

of these variables while adjusting for potential

confounders.

The GAD-7 scores were categorised into

four levels of anxiety severity: minimal (0-4), mild

(5-9), moderate (10-14), and severe (15-21).13 We

conducted sensitivity analysis using the GAD-7 score

as an ordinal outcome and constructed an ordinal

logistic regression model to assess the robustness of

previously identified anxiety-associated factors.

Results

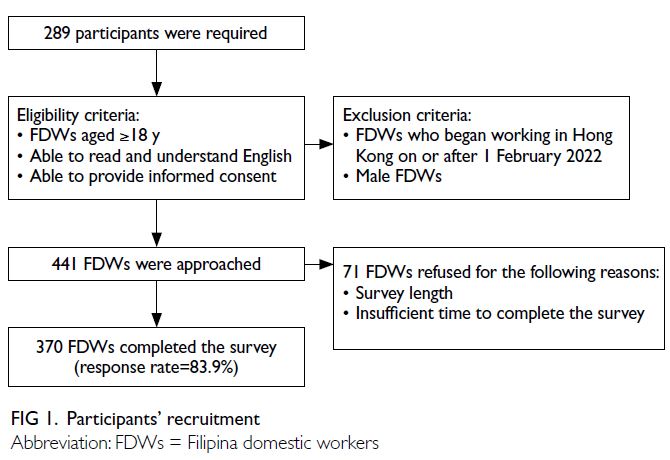

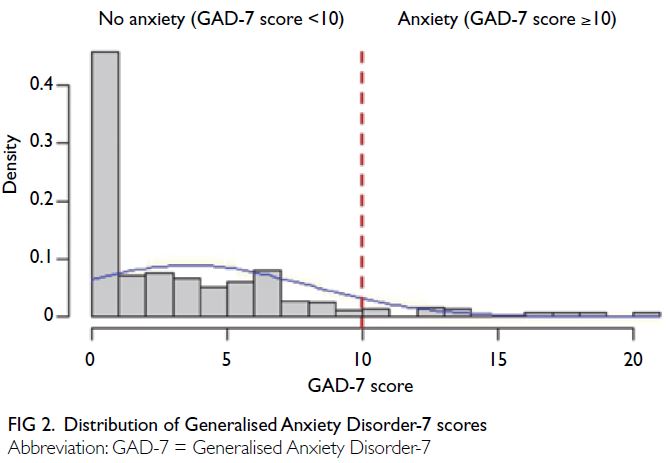

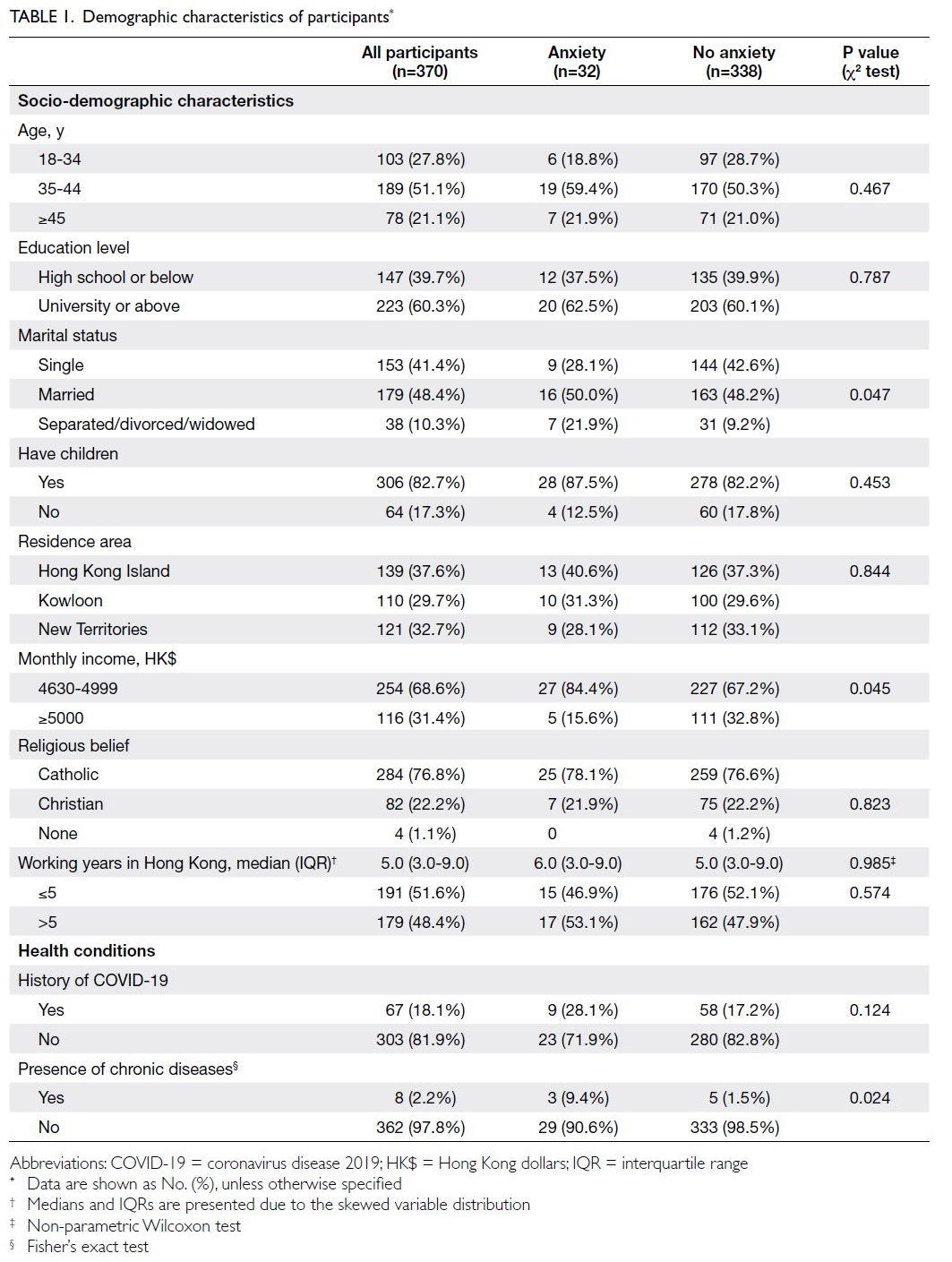

Among the 441 FDWs approached, 71 declined to

participate, yielding a response rate of 83.9% (Fig 1). Primary reasons for refusal were survey length

and time constraints. The distribution of GAD-7

scores was positively skewed (Fig 2). The estimated

prevalence of probable anxiety (GAD-7 score

≥10) was 8.6% (95% CI=5.8-11.5). Among the 370

respondents, approximately half were aged 35 to 44

years (51.1%) and married (48.4%). Most respondents

had attained a university-level education or higher

(60.3%), reported a monthly income ranging

from HK$4630 to HK$4999 (68.6%), and had

children residing in their home country (82.7%).

The proportions of respondents residing on Hong Kong Island, in Kowloon and the New Territories

were evenly distributed. The median (interquartile

range) duration of employment in Hong Kong

was 5.0 years (interquartile range, 3.0-9.0). Most

respondents had no history of COVID-19 (81.9%)

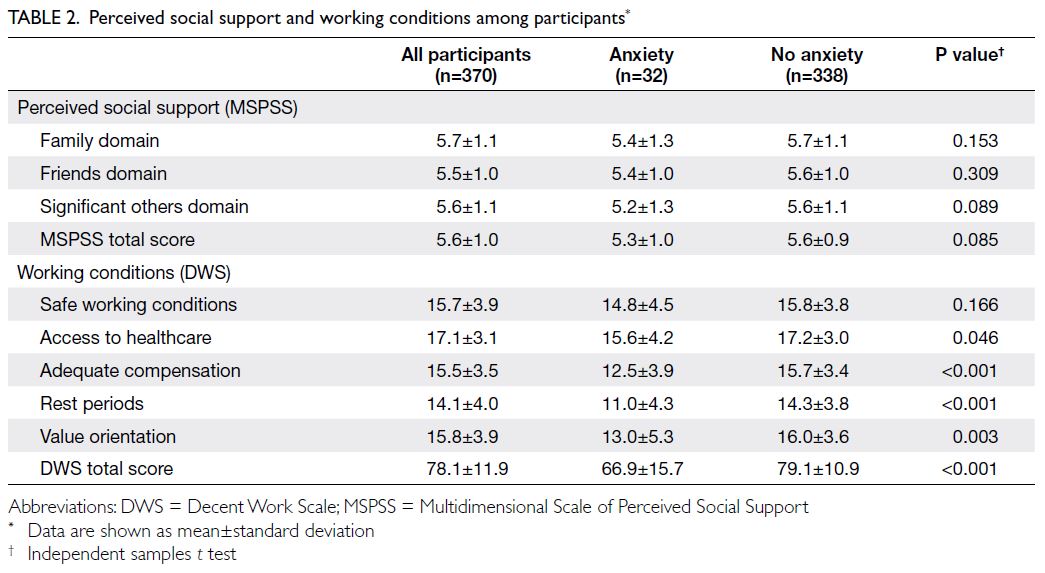

and no chronic diseases (97.8%) [Table 1]. Table 2

shows that the mean scores for the three domains

of perceived social support ranged from 5.5 to 5.7

out of 7, whereas the mean score for decent work

was 78.1 out of 105. Among the five components of

working conditions measured by the Decent Work

Scale, the lowest mean score was observed for rest

periods (14.1); access to healthcare had the highest

mean score (17.1).

Participants with probable anxiety had a

higher proportion of chronic diseases relative to

those without anxiety (9.4% vs 1.5%; P=0.024) [Table 1]. Respondents with probable anxiety reported worse perceptions of social support and working

conditions; they had lower scores across all domains

relative to those of respondents without anxiety

(Table 2).

Associations of perceived social support and

working conditions with anxiety

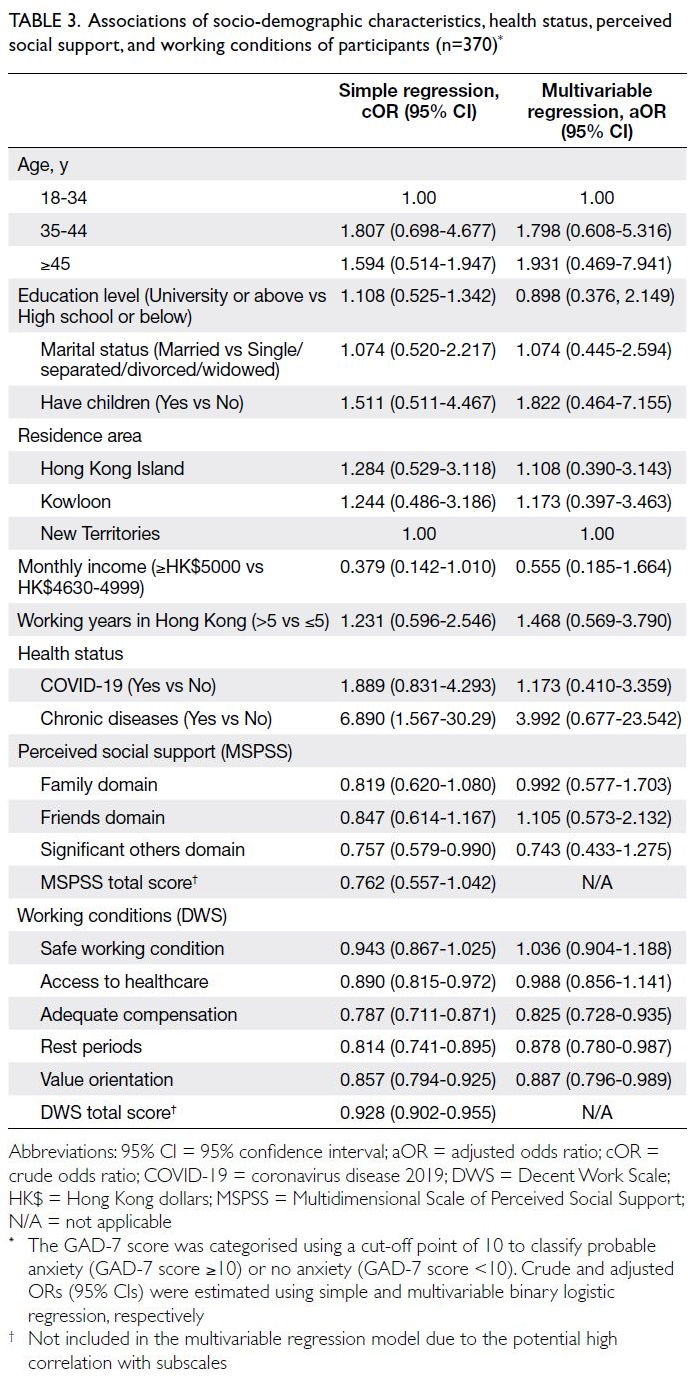

Simple logistic regression analysis indicated that one

domain of perceived social support and multiple

subscales of working conditions were significantly

associated with anxiety (Table 3). Filipina domestic

workers with higher perceived social support from

significant others, better access to healthcare, greater

satisfaction with compensation and salary, increased

free time and rest periods, and higher satisfaction

with their employer’s value orientation exhibited a

lower likelihood of experiencing probable anxiety.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis—adjusted

for all relevant socio-demographic variables, health

status, and subscales of perceived social support and

working conditions—identified three variables that

remained statistically significant (Table 3). Greater

satisfaction with compensation and salary (adjusted

odds ratio [aOR]=0.825, 95% CI=0.728-0.935),

increased free time and rest periods (aOR=0.878,

95% CI=0.780-0.987), and higher satisfaction with

value orientation (aOR=0.887, 95% CI=0.796-0.989)

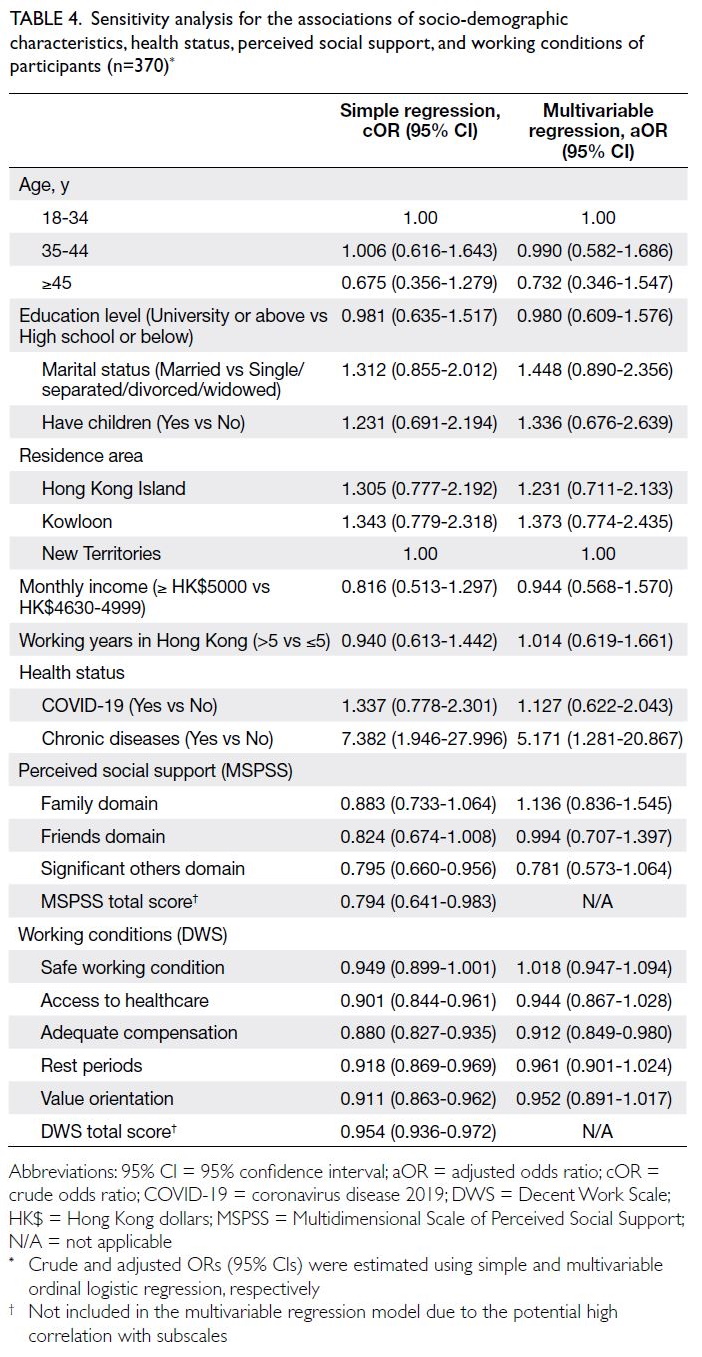

were associated with lower anxiety risk. Sensitivity

analysis, which examined the four levels of anxiety

as an ordinal outcome using an ordinal logistic

regression model, showed that effect estimates

were slightly attenuated. However, the findings

confirmed the association between anxiety levels

and inadequate compensation, while also identifying

a history of chronic diseases as a risk factor for

increased anxiety severity (Table 4).

Table 3. Associations of socio-demographic characteristics, health status, perceived social support, and working conditions of participants (n=370)

Table 4. Sensitivity analysis for the associations of socio-demographic characteristics, health status, perceived social support, and working conditions of participants (n=370)

Discussion

Estimated prevalence of anxiety

The observed prevalence of anxiety among FDWs was 8.6%, representing a lower proportion compared

with previous studies.10 11 21 22 The Omicron variant

led to an unprecedented surge in cases, which

peaked in early March 2022. Compared with a local

study conducted at the onset of the COVID-19

pandemic,10 the prevalence of probable anxiety

among FDWs declined from 25% to 8.6%. A

remarkably lower prevalence of anxiety was

observed when using the official cut-off score of ≥7

for the Anxiety subscale of the Depression, Anxiety,

and Stress Scale-21 Items (DASS-21-A) in both the

general population of Hong Kong (14%)11 and the

Philippines (38.4%).21 In Singapore, 17.5% of migrant

workers exhibited probable anxiety (DASS-21-A

score ≥8).22 The discrepancy in anxiety prevalence

across studies may be attributed to differences in

study contexts and timeframes. Although the fifth

wave of COVID-19 had nearly subsided in Hong

Kong during the present study period, other regions

were still experiencing high caseloads. The relatively

low prevalence of anxiety among FDWs may indicate

the development of psychological resilience after

the Omicron pandemic. Additionally, information

dissemination and vaccine availability were more

established compared with the second and third

waves of the pandemic.10

In response to the fifth wave of the COVID-19

pandemic, the local government implemented

comprehensive public health policies to safeguard

rights and facilitate risk communication among

minority populations in Hong Kong. Coronavirus

disease 2019 and vaccine-related information were

made available in multiple languages, including

Tagalog and English, thereby improving access to

formal and accurate health information for FDWs.

Access to adequate and accurate health information is essential for mitigating psychological distress

and reducing anxiety levels associated with the

pandemic, as demonstrated by the findings of a

study conducted in the Philippines.21

Access to COVID-19 vaccines may partially

explain the findings. In Hong Kong, domestic

workers were designated as a priority group for vaccination within 1 month of launching the

COVID-19 vaccination programme.23 Furthermore,

the initial procurement of 22.5 million vaccine doses

ensured sufficient supply for the entire population,

allowing domestic workers to choose between

Sinovac and BioNTech vaccines at no cost. The high

effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination may have

contributed to anxiety reduction. As of August 2021,

the majority of sampled domestic workers (80%) had

received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine.24

A study by McMenamin et al25 demonstrated the

substantial protective effect of COVID-19 vaccines

against severe or fatal outcomes (BioNTech: two

doses=83.9%; three doses=97.9%). Vaccination

significantly reduces the risk of severe COVID-19

complications, hospitalisation, and mortality, which

may have indirectly alleviated probable anxiety

among FDWs. This assumption is supported by

the results of a study examining the psychological

impact of COVID-19 vaccination, which revealed

lower anxiety levels among vaccinated individuals.26

However, the aforementioned local10 11 20 and

Singapore studies22 assessing the anxiety of migrant

workers were conducted during periods when no

pharmaceutical preventive measures were available.

Therefore, access to COVID-19 vaccines is a

plausible explanation for the lower prevalence of

probable anxiety among FDWs.

Additionally, job security may explain the

decline in probable anxiety. Some FDWs expressed

concerns regarding job insecurity and experienced

distress due to job loss.4 Amid increasing reports

of illegal contract terminations, the government

intervened to uphold FDWs’ employment rights.27

On 5 March 2022, a government spokesperson

emphasised zero tolerance for employers who

illegally dismissed FDWs exhibiting SARS-CoV-2

infection.27 Any violation of the Employment

Ordinance and related laws was subject to

prosecution and fines.27 Filipina domestic workers

exhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection or identified as

close contacts of individuals with COVID-19 receive

the same assistance and support as other Hong

Kong citizens, including quarantine and isolation

arrangements.27 Greater institutional support for

their employment may have contributed to the lower

prevalence of anxiety among FDWs.

Perceived social support and anxiety

The significant others domain of perceived social

support was negatively associated with anxiety in

univariable analysis but was no longer significant

according to multivariable regression. Significant

others are individuals that the respondents regard as

special persons.12 This finding contrasts with previous

studies that identified perceived social support as an

essential factor in coping with psychological distress

among migrant workers.8 9 This discrepancy may be

attributable to the small sample size. However, the

finding is consistent with results from a local study

conducted in a similar context.10

Filipina domestic workers migrate to foreign

countries to support their families’ livelihoods; they

are often portrayed as resilient and independent

figures by the Philippine Government. This narrative

may subtly reinforce the perception among FDWs

that they are the sole breadwinners responsible for

their families’ well-being.28 Consequently, although

FDWs may seek informal social support from

significant others, their self-disclosure remains

selective. Psychological concerns, in particular, may

be considered sensitive topics, leading to avoidance

of such discussions in an effort to protect their self-esteem.

This avoidance may explain the absence of

an observed association between perceived social

support and anxiety.

Working conditions and anxiety

Another key finding was that better working

conditions—including greater satisfaction with

compensation and salary, increased free time and

rest periods, and higher satisfaction with value

orientation—were associated with a lower likelihood

of probable anxiety. Working conditions are

recognised as social determinants of mental health.

Findings from the World Health Organization

suggest that jobs offering high rewards and a greater

sense of control serve as protective factors for mental

well-being, thereby reinforcing the importance of

favourable working conditions for employees.29

Consistent with the previous findings,30 high and

regular monetary compensation was linked to lower

probable anxiety in our study. According to the

Occupational Wages Survey in the Philippines,30 the

median monthly income was PHP13 646 (HK$1865,

US$239), whereas the minimum monthly wage in

Hong Kong was HK$4630 (US$594) during the study

period.31 Filipina domestic workers in Hong Kong

earned at least 2.48-fold more than their counterparts

in the Philippines. Higher monthly earnings are

often allocated toward property purchases in the

Philippines, meeting family obligations, and fulfilling

roles and responsibilities. Thus, greater satisfaction

with compensation and salary may have contributed

to lower probable anxiety among FDWs. Although

this factor may explain the observed association, a

qualitative study would provide deeper insights into

the relationship between higher compensation and

reduced psychological distress.

Additionally, increased free time and rest

periods were associated with a lower risk of probable

anxiety. An occupational health study32 established

an inverse relationship between working hours and

sleep duration, where anxiety and depression scores

were higher among individuals working longer

hours. These findings suggest that increased free

time and rest periods can help reduce anxiety risk.

Notably, greater alignment between FDWs’

working environments and their social values

was associated with lower anxiety risk. Value

orientation refers to the principles an individual

upholds, including ethics, morality, and attitudes toward work. In the workplace, each aspect of the

working environment is interconnected with FDWs

and their employers, influencing the likelihood of

psychological distress. Employers are encouraged

to engage in discussions with FDWs regarding

working conditions—such as job demands and

task restructuring—to ensure alignment in value

orientation between both parties.

Other covariates

While chronic disease was not a statistically

significant predictor of anxiety in multivariable

logistic regression model, sensitivity analysis using

an ordinal outcome revealed that it remained a risk

factor for increased anxiety severity. Despite the

inconclusive findings regarding this association,

a systematic review33 indicated that a history of

chronic diseases is linked to higher anxiety levels.

The presence of chronic diseases has a negative

impact on mental health.33

Limitations and strengths

Some limitations were inherent in our sampling

method and study design. First, we could not establish

causality. Because cross-sectional study designs

provide only short-term data regarding associations,

longitudinal studies are needed to examine temporal

sequences and causal relationships. Second, the use

of convenience sampling may introduce selection

bias; therefore, generalisations of the findings

to the entire FDW population should be made

with caution. However, this bias is likely minimal

because all FDWs were approached, and none were

selectively invited based on specific characteristics;

also, the demographic distribution of the sample

closely resembled that of domestic workers recorded

in the Hong Kong Population Census.34 The age

distributions in the Census data34 and the study

sample were comparable: 18-34 years (29.8% vs

27.8%), 35-44 years (48.2% vs 51.1%), and ≥45 years

(22.0% vs 21.1%). Additionally, the respondents’

residence areas were evenly distributed across Hong

Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories.

These findings suggest high representativeness and

generalisability in the study sample. Furthermore,

monetary incentives were provided, which may have

contributed to higher-quality responses.

Conclusion

This study identified associations between optimal

working conditions and lower probable anxiety

among FDWs. The findings update the estimated

prevalence of anxiety in this population and suggest

that favourable working conditions may serve as

protective factors. The study provides insights

for the development and refinement of public

health measures and occupational policies related

to migrant workers, including compensation for

overtime work, job security, and adequate rest

periods. Psychological interventions tailored to

domestic workers should be developed to address

diverse mental health needs while incorporating

labour protection. Regular review and refinement of

occupational policies may be necessary. The Labour

Department could consider conducting large-scale

quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews with

domestic workers to assess and accommodate their

occupational needs. Future studies should aim to

include domestic workers of various nationalities

and other migrant worker populations.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KKY Lai, ELY Wong.

Acquisition of data: KKY Lai.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKY Lai.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ELY Wong.

Acquisition of data: KKY Lai.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKY Lai.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ELY Wong.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Prof Marc KC Chong, Ms Annie WL

Cheung and Mr Jonathan CH Ma from the Centre for Health

Systems and Policy Research, The Jockey Club School of Public

Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong

Kong for their valuable comments on the study and support

in data analysis. The authors also thank all study respondents

for their valuable time in completing the questionnaires and

for their contributions as migrant workers in Hong Kong.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Survey and Behavioural

Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University

of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 018-22). The study

was conducted in accordance with the principles of the

Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from

the participants prior to commencement of the survey.

References

1. Centre for Health Protection and Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Statistics on 5th wave of COVID-

19 (from 31 Dec 2021 up till 31 May 2022 00:00). Available

from: https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/pdf/5th_wave_statistics/5th_wave_statistics_20220531.pdf . Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

2. Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19

pandemic on mental health in the general population: a

systematic review. J Affect Disord 2020;277:55-64. Crossref

3. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. 2021 Population Census. Main Results.

Available from: https://www.census2021.gov.hk/doc/pub/21c-main-results.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2025.

4. Chow Y. No home away from home for domestic workers

terminated after contracting coronavirus amid Hong

Kong’s fifth wave. Young Post. South China Morning Post;

2022 May 16. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/yp/discover/news/hong-kong/article/3177657/no-home-away-home-domestic-workers-terminated-after. Accessed 4 Dec 2022.

5. Cheung JT, Tsoi VW, Wong KH, Chung RY. Abuse and

depression among Filipino foreign domestic helpers.

A cross-sectional survey in Hong Kong. Public Health

2019;166:121-7. Crossref

6. Choy CY, Chang L, Man PY. Social support and coping

among female foreign domestic helpers experiencing

abuse and exploitation in Hong Kong. Front Commun 2022;7:1015193. Crossref

7. Sterud T, Tynes T, Mehlum IS, et al. A systematic review

of working conditions and occupational health among

immigrants in Europe and Canada. BMC Public Health

2018;18:770. Crossref

8. Ioannou M, Kassianos AP, Symeou M. Coping with

depressive symptoms in young adults: perceived social

support protects against depressive symptoms only under

moderate levels of stress. Front Psychol 2019;9:2780. Crossref

9. Straiton ML, Aambø AK, Johansen R. Perceived

discrimination, health and mental health among

immigrants in Norway: the role of moderating factors.

BMC Public Health 2019;19:325. Crossref

10. Yeung NC, Huang B, Lau CY, Lau JT. Feeling anxious

amid the COVID-19 pandemic: psychosocial correlates

of anxiety symptoms among Filipina domestic helpers in

Hong Kong. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8102. Crossref

11. Choi EP, Hui BP, Wan EY. Depression and anxiety in Hong

Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2020;17:3740. Crossref

12. Duffy RD, Allan BA, England JW, et al. The development

and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. J Couns

Psychol 2017;64:206-21. Crossref

13. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief

measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the

GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092-7. Crossref

14. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers

Assess 1988;52:30-41. Crossref

15. International Organization for Migration. The

Determinants of Migrant Vulnerability. Geneva: United

Nations; 2019. Available from: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/our_work/DMM/MPA/1-part1-thedomv.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

16. Garabiles MR, Lao CK, Yip P, Chan EW, Mordeno I, Hall

BJ. Psychometric validation of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in

Filipino migrant domestic workers in Macao (SAR), China.

J Pers Assess 2020;102:833-44. Crossref

17. Mendoza NB, Mordeno IG, Latkin CA, Hall BJ. Evidence

of the paradoxical effect of social network support: a study

among Filipino domestic workers in China. Psychiatry Res

2017;255:263-71. Crossref

18. Yeung NC, Kan KK, Wong AL, Lau JT. Self-stigma,

resilience, perceived quality of social relationships, and

psychological distress among Filipina domestic helpers in

Hong Kong: a mediation model. Stigma Health 2021;6:90-9. Crossref

19. Pan American Health Organization. Questionnaire to

Assess the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Diseases.

Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from:

https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/cncd_mgt_questionnaire.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2022.

20. Leung DD, Tang EY. Correlates of life satisfaction among

Southeast Asian foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong:

an exploratory study. Asian Pac Migr J 2018;27:368-77. Crossref

21. Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, et al. Psychological impact

of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord

2020;277:379-91. Crossref

22. Saw YE, Tan EY, Buvanaswari P, Doshi K, Liu JC. Mental

health of international migrant workers amidst large-scale

dormitory outbreaks of COVID-19: a population survey in

Singapore. J Migr Health 2021;4:100062. Crossref

23. Labour Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Foreign domestic helpers. Vaccination priority groups to

be expanded to cover people aged 30 or above. 2021 Mar 15.

Available from: https://www.fdh.labour.gov.hk/en/news_detail.html?year=2021&n_id=190. Accessed 28 Mar 2025.

24. Sumerlin TS, Kim JH, Wang Z, Hui AY, Chung RY.

Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among female

foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional

quantitative survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2022;19:5945. Crossref

25. McMenamin ME, Nealon J, Lin Y, et al. Vaccine effectiveness

of one, two, and three doses of BNT162B2 and CoronaVac

against COVID-19 in Hong Kong: a population-based

observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022;22:1435-43. Crossref

26. Babicki M, Malchrzak W, Hans-Wytrychowska A,

Mastalerz-Migas A. Impact of vaccination on the sense

of security, the anxiety of COVID-19 and quality of life

among polish. A nationwide online survey in Poland.

Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:1444. Crossref

27. Hong Kong SAR Government. Government’s response on

situation of foreign domestic helpers affected by COVID-19 (with photos) [press release]. 2022 Mar 5. Available

from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202203/05/P2022030500399.htm. Accessed 4 Dec 2022.

28. Rich GJ. Filipina migrant domestic workers in Asia:

mental health and resilience. In: Rich GJ, Jaafar JL, Barron

D, editors. Psychology in Southeast Asia: Sociocultural,

Clinical, and Health Perspectives. London: Routledge,

Taylor & Francis Group; 2020. Crossref

29. World Health Organization. Social determinants of mental

health. 2014 May 18. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506809. Accessed 1 Apr 2025.

30. Mapa DS. Average monthly wage rates of selected

occupations: 2018 and 2020 [Internet]. 2020 Occupational

Wages Survey (OWS). Philippine Statistics Authority; 2022.

Available from: https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/occupational-wages-survey/node/168472. Accessed 4 Dec 2022.

31. Hong Kong SAR Government. Minimum allowable wage

and food allowance for foreign domestic helpers [press

release]. 2021 Sep 30. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202109/30/P2021093000329.htm. Accessed 4 Dec 2022.

32. Afonso P, Fonseca M, Pires JF. Impact of working hours on

sleep and mental health. Occup Med (Lond) 2017;67:377-82. Crossref

33. Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their

relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the

epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust

2009;190:S54-60. Crossref

34. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. 2021 Population Census: Summary

Results. 2022. Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1120106/att/B11201062021XXXXB01.pdf . Accessed 4 Dec 2022.