Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 1 Apr 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Filicide (child homicide by parents) in Hong Kong

Yuen Dorothy Yee Tang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Psychiatry)1; Jessica PY Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Psychiatry)2; Amy CY Liu, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Psychiatry)1; Bonnie WM Siu, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Psychiatry)1

1 Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Psychiatry, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Yuen Dorothy Yee Tang (tyy551@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Filicide refers to an act in which a

parent or stepparent kills a child. This retrospective

study provides the first comprehensive analysis of

filicides in Hong Kong over a 15-year period.

Methods: The study explored the local epidemiology,

differences between maternal and paternal filicides,

associated mental illnesses, and the criminal

responsibility of the perpetrators.

Results: Among 81 filicide cases (43 female

victims, 37 male victims, and 1 victim of unknown

gender), the incidence rate was 0.7 per 100 000

population. Mothers were responsible for two-thirds

(66.7%) of the cases, fathers for 19.8%, and

the remainder involved both parents. Victims aged

<1 year (n=44) were nearly equal in number to

those aged between 1 and 17 years (n=41). Mental

illness was diagnosed in 31.0% of the perpetrators,

predominantly depression and psychotic disorders.

Paternal perpetrators exhibited a higher prevalence

of mental illness and were more frequently involved

in filicide-suicides. One-third (33%) of perpetrators

with mental illness invoked the psychiatric defence of diminished responsibility, resulting in Hospital

Order sentencing. Reduced culpability due to mental

illness and the application of infanticide provisions

provided legal protections for mothers who killed

their children aged <1 year.

Conclusion: Understanding the local epidemiology

of filicide and the mental health conditions of

perpetrators may help identify at-risk populations

and develop effective intervention strategies.

New knowledge added by this study

- The epidemiology, differences between maternal and paternal filicides, associated mental illnesses, and the criminal responsibility of the perpetrators in Hong Kong from 2003 to 2017 were explored.

- Maternal perpetrators were disproportionately responsible for infanticides, highlighting the protective legal provisions applied to mothers who kill their children aged <1 year.

- Understanding the local epidemiology of filicide and the mental health conditions of perpetrators may help identify at-risk populations and develop effective intervention strategies.

- Enhanced mental health screening and support for parents, particularly mothers of infants, could potentially prevent cases of filicide.

Introduction

Child homicide represents a rare but important

global issue with devastating consequences for

families and communities. The global homicide

rate among children aged 0 to 17 years was 1.6 per

100 000 population in 2016,1 and approximately

95 000 children are murdered annually.2 A 2017

review by Stöckl et al3 found that the majority of child

homicides were committed by a family member;

parents were responsible for over half of the cases

involving child victims.3

Filicide

Filicide refers to the act of killing one’s own child.

Subcategories of filicide include neonaticide, a term introduced by Resnick4 to describe the murder of

a child within the first 24 hours after birth, and

infanticide, which applies when the victim is aged <1

year. Resnick4 identified various motives for filicide. In

altruistic filicide, the parent believes that the act is in

the child’s best interests. An acutely psychotic parent

may kill a child under the influence of severe mental

illness. In unwanted child filicide, a parent kills a child

who is perceived as a hindrance. Accidental/fatal

maltreatment describes the unintentional death of a

child due to parental abuse or neglect. Spouse revenge

filicide occurs when a child is killed as a means

of exacting revenge upon the spouse or the other

parent. Bourget and Bradford5 later emphasised the

importance of the perpetrator’s gender by introducing

paternal filicide as a distinct category.

Victim and perpetrator characteristics

vary in cases of filicide. The first year of life is

a critical period, and the highest risk of filicide

occurs within the first 24 hours. Neonaticides are

predominantly committed by mothers,6 and mothers

are overrepresented across the entire spectrum of

filicide.4 5 However, contradictory results have been

reported.5 7 8 The gender distribution of victims also

varies. Male children aged <1 year are at greater risk

in high-income Western countries, such as the US9

and the UK10; the opposite trend has been observed

in India and China.11 Some studies have shown that

boys are overrepresented among victims,7 12 whereas

others have identified comparable numbers of male

and female filicide victims.13

Maternal and paternal perpetrators of filicide

exhibit distinct characteristics.14 15 Maternal

perpetrators tend to be younger and have younger

victims compared with fathers.15 Younger maternal

perpetrators are often poor, experience psychosocial

stress, and lack family and community support,

whereas older maternal perpetrators frequently have

mental illnesses and lack criminal histories.13 14 16 In

contrast, paternal perpetrators are more commonly

driven by anger, jealousy, or marital and life

discord.15 Fatal abuse and acts of retaliation are more

prevalent among paternal perpetrators than among

maternal perpetrators.17 Fathers are also more likely

to attempt or die by suicide12 17 18 when committing

filicide.14 18 Additionally, fathers typically use more violent methods to cause death.19

Filicide and mental illness

Pathological filicide, characterised by altruistic or actively psychotic motives, constitutes one

of the most common categories of filicide.17

Psychiatric factors are involved in 36% to 85% of

all filicide cases.5 16 20 21 22 Maternal perpetrators are

more likely to have a history of mental illness and

to exhibit symptoms at the time of the offence.22

The most frequent diagnosis among maternal

perpetrators is major depressive disorder, followed

by schizophrenia.5 16 20 23 Personality disorders and substance use are more often associated with

paternal filicides.8

The criminal justice system and infanticide

laws

Filicide presents unique challenges for the criminal

justice system. Societal attitudes regarding parents

who kill their children are often ambivalent,

balancing the need for justice due to loss of innocent

life against calls for mercy towards offenders who

may require care rather than punishment.

Legal systems worldwide acknowledge that

filicide should be treated differently from other forms

of homicide. The UK enacted the Infanticide Act in

1922 (amended in 1938)24 to recognise the biological

vulnerability of women to psychiatric illnesses

during the perinatal period. The Act mandated

sentences of probation and psychiatric treatment for

offenders.24 By the late 20th century, 29 countries had

revised penalties for infanticide to consider unique

biological and psychological changes associated with

childbirth.25

In Hong Kong, perpetrators with mental

illnesses can invoke psychiatric defences, including

insanity or diminished responsibility. The insanity

defence is based on the M’Naghten principles, which

hold that it is unjust to punish an individual for an

action performed without the mental capacity to

control it. The defence of diminished responsibility

applies when the offender demonstrates abnormal

mental function arising from a recognised medical

condition, which has substantially impaired their

ability to either understand the nature of their

conduct, form a rational judgement, or exercise self-control

(or any combination of these impairments).

Perpetrators with mental illnesses who are found not

guilty by reason of insanity, or who successfully raise

the partial defence of diminished responsibility—thereby reducing the charge from murder to

manslaughter—may be sentenced to a Hospital

Order at the Correctional Services Department

Psychiatric Centre (Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre

[SLPC]), under Section 75 of the Criminal Procedure

Ordinance26 or Section 45 of the Mental Health

Ordinance,27 respectively, for psychiatric observation

and management.

A separate legal provision exists for mothers

who kill their children aged <1 year. Hong Kong has

adopted the UK concept of infanticide, in which mothers experiencing vulnerability after childbirth

are charged with infanticide rather than murder,

under Section 47C of the Offences against the Person

Ordinance.28

A study has shown that the local homicide rate

in Hong Kong is lower than global averages (0.32 vs

6.1 victims per 100 000 population in 2017),29 but no

filicide-specific data are available. The underlying

hypothesis in this study was that the incidence

of filicide would be lower in Hong Kong than in

Western countries, consistent with the lower local

homicide rate and the protective effects of cultural

factors. The objectives of this study were to describe

the epidemiology of filicide in Hong Kong, examine

the characteristics of victims and perpetrators

(including associated mental illnesses), and evaluate

the local criminal justice system’s response to

infanticide and other forms of filicide.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Hong Kong Police Force

regarding child homicide cases that occurred from

2003 to 2017. These data included the age and gender

of the victim, relationship of the perpetrator to the

victim, mode of death, year of offence, and charges

against the defendant along with corresponding

outcomes and sentences. Medical records from the

Hospital Authority and the SLPC of the Correctional

Services Department were reviewed to determine

any history of mental illness. Psychiatric diagnoses

of the perpetrators, based on the International

Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, were

documented during forensic psychiatric assessments

conducted by two psychiatrists, at least one of whom

was a specialist. For the minority of defendants who

were not sent to psychiatric hospitals or SLPC after

the offences, the presence or absence of mental

illness was cross-referenced using newspaper

articles. Charges and sentences were verified

through judgements available on the Judiciary’s

official website.

All statistical analyses were performed using

SPSS software (Windows version 21.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], US). Data were analysed with

descriptive statistics, including the mean, median,

standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, and

percentages for categorical variables. Differences

between groups in demographic characteristics

were assessed using t tests and univariate analysis of

variance for continuous data. For nominal data, the

Kruskal–Wallis and Chi squared tests were utilised.

Results

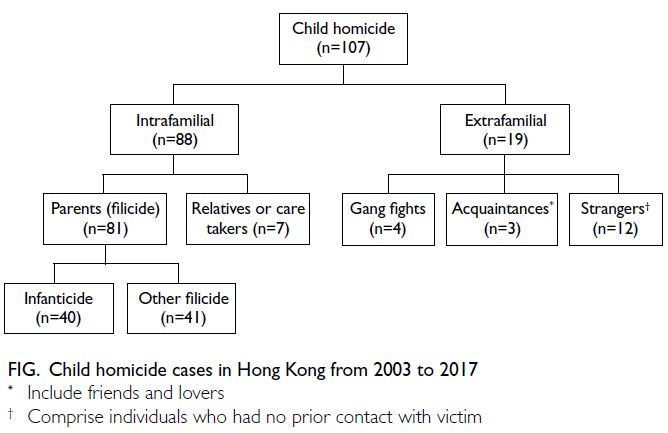

Epidemiology of child homicide

From 2003 to 2017, 107 child homicide victims were

recorded in Hong Kong, equating to approximately

0.70 death per 100 000 population, based on a population of 1 024 000 children aged <18 years in

2010.30 Among these victims, 81 (75.7%) were killed

by their parents (Fig).

Characteristics of victims and perpetrators

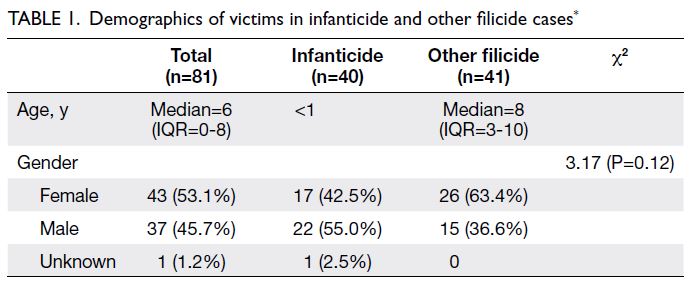

Among the filicide victims (n=81), 53.1% were

female, 45.7% were male, and the gender of the

remaining victim was unknown. There was no

significant correlation between the gender of the

victim and the gender of the perpetrator (χ2=0.13;

P=0.82). The median age of the victims was 6 years

(interquartile range [IQR]=0-8) [Table 1].

Of the 81 filicide victims, 54 (66.7%) were killed

by their mothers, 16 (19.8%) by their fathers, and 11

(13.6%) by both parents. The median age of victims

varied across perpetrator groups; the paternal group

victims had a median age of 7.5 years (IQR=5-10.25),

compared with 0 year (IQR=0-3.5) for the maternal

group and 2 years (IQR=0-5) for the parental couple

group (H2=14.31; P<0.001).

Characteristics of infanticide and other

filicide cases

Forty victims aged <1 year were killed by 44 perpetrators, and 41 victims aged ≥1 year were killed

by 40 perpetrators. No significant gender differences

were observed among the victims (Table 1).

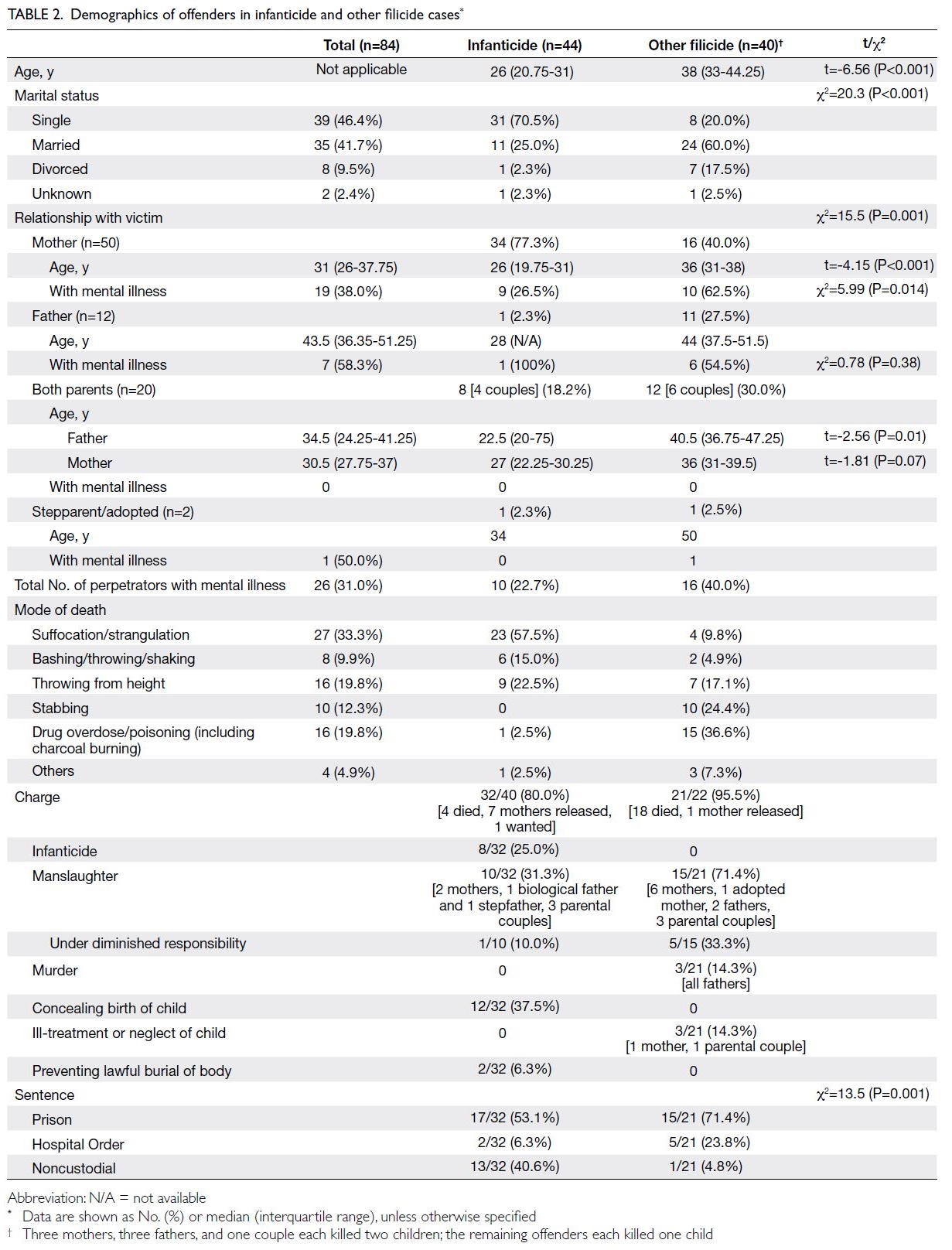

The median age of paternal perpetrators,

43.5 years, was significantly older than the median

ages of maternal and parental couple perpetrators

(H2=16.50; P<0.001). The median age of offenders

in the infanticide group was younger than that of

offenders in the other filicide group. In the infanticide

group, nine mothers (26.5%) were <20 years, and all

pregnancies had been concealed. These infants were

killed immediately after birth. Single offenders were

more prevalent in the infanticide group, whereas

married offenders were more common in the other

filicide group. Biological mothers were the main

perpetrators in both groups; similar to paternal and

couple perpetrators, maternal perpetrators were

younger in the infanticide group (Table 2). The

maternal group was responsible for 40% of victims

aged <4 years, compared with 7.1% in the paternal

group. A higher prevalence of mental illness was

identified among perpetrators, particularly mothers,

in the other filicide group. Among perpetrators

in the infanticide group, depression (40%) was the

most common diagnosis, followed by a psychotic

disorder (20%), mental and behavioural disorders

due to psychoactive substance use (20%), and mental

retardation (20%). The only biological father in the

infanticide group was diagnosed with harmful use of

alcohol. In the other filicide group, among maternal

perpetrators, 25.0% had a psychotic disorder, 18.8%

had depression, 6.4% had bipolar affective disorder,

and the remainder had unknown diagnoses. Among

paternal perpetrators, 18.0% had depression, 9.1%

had a psychotic disorder, and the remainder had

undocumented diagnoses.

Suffocation or strangulation was the most

common mode of death in infanticides, occurring

in 95.7% of cases with maternal perpetrators. In

contrast, paternal perpetrators (100%) and couples

(50%) caused death mainly by bashing, throwing, or

shaking the infants. The two most common modes

of death across all filicides were drug overdose or

poisoning (including charcoal burning) and stabbing.

Drug overdose or poisoning was most frequently

performed by maternal perpetrators (36.8%) and

couples (57.1%), whereas paternal perpetrators most

often engaged in stabbing (57.1%).

Excluding the four perpetrators who died by

suicide, 80.0% of perpetrators in the infanticide group

faced criminal charges and were convicted. The most

common convictions were concealing the birth of a

child, manslaughter, and infanticide (Table 2). In the

other filicide group, excluding the 18 perpetrators

who died by suicide, 95.5% of perpetrators were charged and convicted; manslaughter was the most

common conviction, followed by murder. Sentences

significantly differed between the infanticide and

other filicide groups. Noncustodial sentences were

more frequent in the infanticide group than in the

other filicide group. Given the higher prevalence

of mental illness in the other filicide group, 33.3%

(5/15) of the perpetrators were convicted of

manslaughter under diminished responsibility and

sentenced to a Hospital Order, compared with 6.3%

in the infanticide group (Table 2). Among paternal

and couple perpetrators, 80% in the infanticide

group and 92.3% in the other filicide group received

prison sentences, ranging from 3 to 10 years and 18

months to life imprisonment, respectively. Similar

proportions of maternal perpetrators in both

groups—41.0% in the infanticide group and 42.9% in

the other filicide group—were imprisoned. Among

maternal perpetrators in the infanticide group,

all but one received prison sentences of <1 year;

the exception received an 8-year sentence. In the

other filicide group, maternal perpetrators received

sentences of 4 to 7 years.

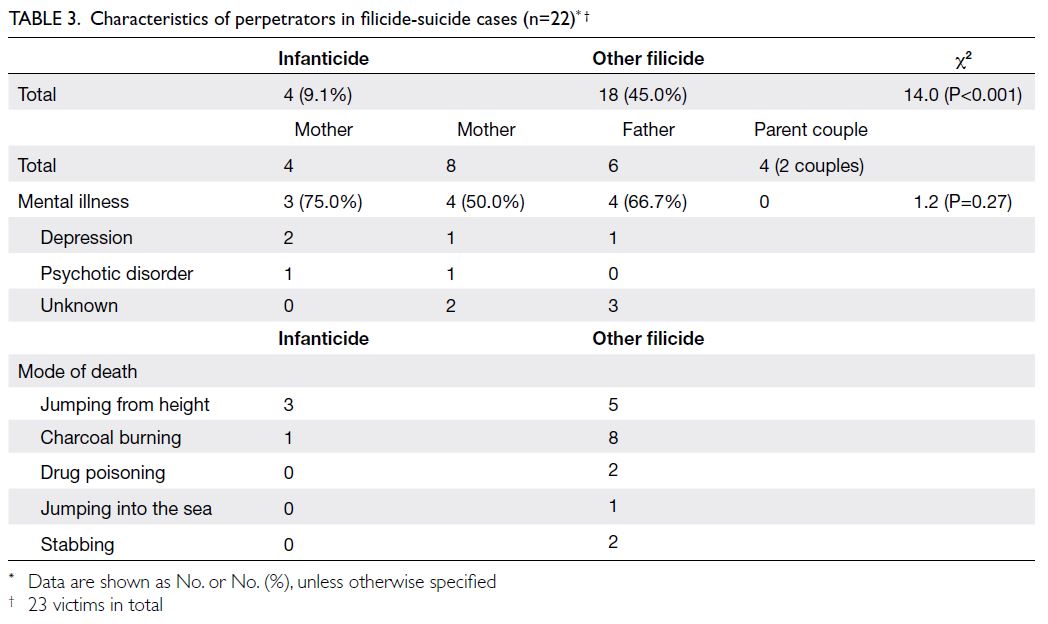

Filicide-suicide is defined as the perpetrator

dying by suicide within 24 hours of committing

filicide. A significantly greater proportion of filicide-suicides

occurred in the other filicide group. In the

infanticide group, all perpetrators were biological

mothers. In contrast, within the other filicide group,

half of maternal perpetrators and 66.7% of paternal

perpetrators had a diagnosed mental illness. The

difference in mental illness prevalence between the

two groups was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Mental illness of filicide offenders

Of the 84 filicide perpetrators, 26 (31.0%) were

diagnosed with mental illness. No mental illness

was reported in the parental couple group. A higher

prevalence of mental illness was observed among

paternal perpetrators (58.3%) than among maternal

perpetrators (38.0%), although the difference was

not statistically significant. Depression was the most

common diagnosis, followed by psychotic disorder.

In cases of filicide-suicide, mental illness prevalence

was higher among paternal perpetrators; this

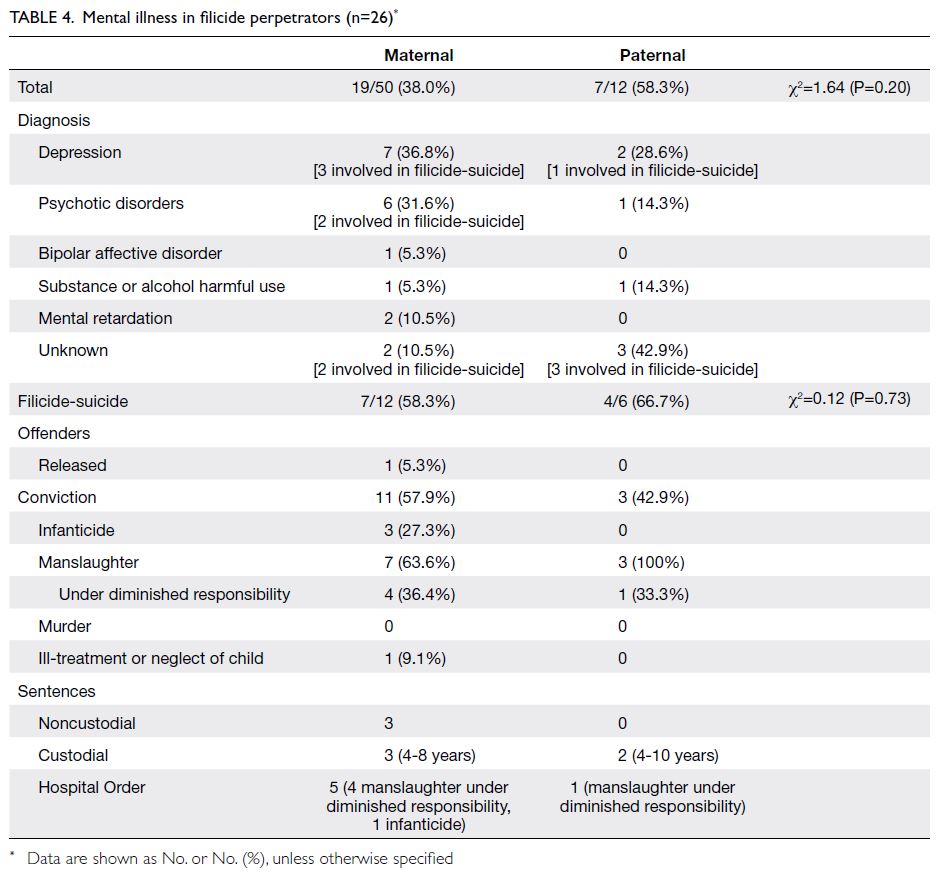

difference was not statistically significant (Table 4).

Excluding perpetrators who died by suicide,

41.7% of maternal perpetrators with mental illness

received a Hospital Order for an unspecified period.

Among the three paternal perpetrators with mental

illness who did not die by suicide, only one (33.3%)

was sentenced to a Hospital Order for an unspecified

period.

Discussion

The incidence of child homicide in Hong Kong, at

0.7 per 100 000 population, is lower than the global average (1.6 per 100 000 population)1 and lower than

that of Asian countries with similar socio-economic

status, such as South Korea (1.03 per 100 000

population).31 The protective influence of traditional

Confucian cultural values may play a prominent role

in Hong Kong.32 An idiom from the Sung dynasty,

‘even a vicious tiger would not eat its cubs’, continues

to be taught in modern primary schools. This cultural

ethos could explain why the incidence of child

maltreatment in Hong Kong, at <0.14%,30 remains

lower than the global rate of 0.3% to 0.4%.33 Consistent

with studies worldwide,3 most child homicides in

Hong Kong were perpetrated by parents. Mothers

were the predominant perpetrators in filicides. The

typical profile of an infanticidal perpetrator was a

young, single mother who suffocated or strangled

the infant. Some cases may represent neonaticides,

as suggested by charges of concealing the birth of

a child. Among cases involving the filicide of older

children, perpetrator characteristics were more

heterogeneous. Perpetrators tended to be older and

married; they used methods such as overdosing,

poisoning, or stabbing. The profiles of perpetrators

and victims in this group also differed. The median

age of maternal perpetrators was younger and their

victims tended to be younger. Mothers most often

caused death through overdosing or poisoning,

whereas fathers were more likely to kill by stabbing.

Mental illness in filicides

In the present study, 31.0% of filicidal perpetrators

had a diagnosed mental illness, a lower rate

compared with other population studies.8 20 22 23 This discrepancy could be attributed to the lower

prevalence of mental illness in Hong Kong. The

Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey (2010-2013)

revealed a 13.3% prevalence of mental disorders

among Chinese adults,34 compared with 18.5%

among adults in the US in 2013.35 It is also plausible

that some perpetrators, especially those involved

in filicide-suicide cases, had no prior contact

with mental health services and may have had

undiagnosed psychiatric illnesses. Mental illness

prevalence was higher among paternal perpetrators

than among maternal perpetrators in our filicide

sample. This finding may be related to the small

sample size or could reflect societal changes, such as

fathers assuming greater childcare responsibilities.17

Consistent with some studies,20 22 depression was

the most common diagnosis, followed by psychotic

disorder.

Filicide-suicides

Substantial proportions of filicide perpetrators

(23.0% of maternal and 34.8% of paternal) died by

suicide during or after committing the act. Charcoal

burning was the most common method, comparable

to the frequency of jumping from height. Charcoal

burning is a relatively recent suicidal method,36 which

has spread as a contagious phenomenon in other

Asian countries; it is often portrayed as a ‘peaceful

way of dying’ and has been used during >10% of

suicides in the region.37 The proportion of filicide-suicides

observed in this study was lower than that

reported in other studies.17 23 This difference may be

related to the lower prevalence of mental illness in our sample, the relatively lower lethality of charcoal

burning in Hong Kong compared with firearm use in

Western countries, or the possibility that attempted

suicides not resulting in death were not captured in

our data. Filicide-suicide events were more frequent

in cases involving older children than in infanticides,

potentially due to differences in underlying motives.

Half of the filicide-suicide perpetrators in the present

study had a history of mental illness, suggesting that

altruistic motives were involved. Depression was

the most frequently diagnosed condition in these

cases.18 20

The local law and filicides

The majority of perpetrators with mental illness

were convicted of manslaughter under diminished

responsibility and sentenced to a Hospital Order

at SLPC for an unspecified period under Section

45 of the Mental Health Ordinance.27 No insanity pleas were recorded in our sample. Consistent with

international studies,38 maternal perpetrators in

Hong Kong received more lenient outcomes relative

to paternal perpetrators. Some young mothers who

killed their children aged <1 year were released

without charge; among those convicted, a few

received noncustodial sentences. In contrast, all

fathers who killed their children were imprisoned,

with the exception of one who was sentenced to a

Hospital Order at SLPC.

Hong Kong developed its legislation based

on the UK law, including the British Infanticide Act

of 1922.21 24 Section 47C of the Offences against the

Person Ordinance28 defines the offence of infanticide

as follows: “Where a woman by any wilful act or

omission causes the death of her child being a child

under the age of 12 months but at the time of the act

or omission the balance of her mind was disturbed

by reason of her not having fully recovered from the

effect of giving birth to the child or by reason of the effect of lactation consequent upon the birth of the

child, then, notwithstanding that the circumstances

were such that but for the provisions of this section

the offence would have amounted to murder, she

shall be guilty of infanticide, and shall be liable to

be punished as if she were guilty of manslaughter.”

In the present study, eight mothers who killed

their children aged <1 year were convicted under

the infanticide provision. There appears to be

considerable application of this provision in Hong

Kong; lenient noncustodial sentences are issued to

mothers in such cases.

Limitations

First, information provided by the Police was

restricted to arrest cases; thus, the study may

underreport the true incidence of filicides in

Hong Kong. Second, although multiple sources

of information were utilised, details regarding the

perpetrators’ and victims’ abuse or victimisation

histories, involvement with social services, or autopsy

reports were unavailable. Third, the classification of

neonaticides was challenging, although charges of

concealing the birth of a child may indicate the death

of a victim within 24 hours of birth. Fourth, although

most diagnoses of offenders with mental illnesses

were accessible, the availability of psychiatric records

was limited. Information for a small number of cases

(<5) was obtained from newspaper reports. Sixth,

the absence of critical details, such as the onset of

mental illness, symptomatology, and medication

adherence, impeded a thorough exploration of the

relationship between mental illness and filicides. A

more comprehensive approach, such as conducting

psychological autopsies—particularly in filicide-suicide

cases—would provide deeper insights.

Finally, the sample size was insufficient to allow

for robust comparisons among perpetrators in

maternal, paternal, parental couple, and stepparent

filicide groups.

Conclusion

In this study, most child homicides were perpetrated

by parents; mothers committed filicide more

frequently than fathers. Maternal perpetrators and

their victims were younger than their counterparts

in the paternal perpetrator group. Mental illness

was prevalent among filicidal perpetrators of both

genders, with a higher prevalence in paternal

perpetrators. Filicide-suicide is a substantial problem.

Psychiatrists should remain vigilant in identifying

depressed or psychotic parents and in eliciting self-harm

or filicidal ideations among both mothers and

fathers. Social support and child protection services

should be actively offered to young single mothers.

In Hong Kong, a comprehensive child development

service has been established since 2005,39 with the aim of identifying and intervening early in cases that

involve children and mothers in need; this service

seeks to improve health outcomes for children and

families. However, no local policies specifically

address the needs of fathers. A multidisciplinary

approach involving mental health professionals

and social workers is recommended to screen

fathers experiencing mental illness or distress

and to identify early warning signs of risk. Finally,

given the high prevalence of mental illness among

filicidal perpetrators, forensic psychiatrists and

related professionals should maintain a high index

of suspicion for the presence of mental illness when

evaluating filicidal offenders.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YDY Tang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YDY Tang, JPY Lam.

Drafting of the manuscript: YDY Tang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: YDY Tang.

Acquisition of data: YDY Tang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YDY Tang, JPY Lam.

Drafting of the manuscript: YDY Tang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: YDY Tang.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the New Territories West

Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority,

Hong Kong (Ref No.: NTWC/REC/19021). A waiver for

informed patient consent was granted by the Committee due

to the retrospective nature of the research.

References

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Study

on Homicide. Killing of Children and Young Adults. 2019.

Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/Booklet_6new.pdf. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

2. UNICEF. Hidden in plain sight: a statistical analysis of

violence against children. New York: United Nations

International Children’s Emergency Fund. 2014 Sep 4.

Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/hidden-in-plain-sight-a-statistical-analysis-of-violence-against-children/. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

3. Stöckl H, Dekel B, Morris-Gehring A, Watts C, Abrahams N.

Child homicide perpetrators worldwide: a systematic

review. BMJ Paediatr Open 2017;1:e000112. Crossref

4. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review

of filicide. Am J Psychiatry 1969;126:325-34. Crossref

5. Bourget D, Bradford JM. Homicidal parents. Can J

Psychiatry 1990;35:233-8. Crossref

6. Wilson RF, Klevens J, Fortson B, Williams D, Xu L, Yuan K. Neonaticides in the United States—2008-2017. Acad Forensic Pathol 2022;12:3-14. Crossref

7. Vanamo T, Kauppi A, Karkola K, Merikanto J, Räsänen E.

Intra-familial child homicide in Finland 1970-1994:

incidence, causes of death and demographic characteristics.

Forensic Sci Int 2001;117:199-204. Crossref

8. Bourget D, Gagné P. Paternal filicide in Québec. J Am Acad

Psychiatry Law 2005;33:354-60.

9. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic

understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32

years of U.S. arrest data. Forensic Sci Int 2014;236:46-53. Crossref

10. Brookman F, Nolan J. The dark figure of infanticide in

England and Wales: complexities of diagnosis. J Interpers

Violence 2006;21:869-89. Crossref

11. Sahni M, Verma N, Narula D, Varghese RM, Sreenivas V,

Puliyel JM. Missing girls in India: infanticide, feticide

and made-to-order pregnancies? Insights from hospital-based

sex-ratio-at-birth over the last century. PLoS One

2008;3:e2224. Crossref

12. Dawson M. Canadian trends in filicide by gender of the

accused, 1961–2011. Child Abuse Negl 2015;47:162-74. Crossref

13. Camperio Ciani AS, Fontanesi L. Mothers who kill their

offspring: testing evolutionary hypothesis in a 110-case

Italian sample. Child Abuse Negl 2012;36:519-27. Crossref

14. Harris GT, Hilton NZ, Rice ME, Eke AW. Children killed

by genetic parents versus stepparents. Evol Hum Behav

2007;28:85-95. Crossref

15. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill

their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci

2009;54:463-8. Crossref

16. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by

mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge

and a research agenda. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1578-87. Crossref

17. Bourget D, Grace J, Whitehurst L. A review of maternal and

paternal filicide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2007;35:74-82.

18. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, Noffsinger SG,

Resnick PJ. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents

who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad

Psychiatry Law 2005;33:496-504.

19. West SG, Hatters Friedman S. Filicide: a research update.

In: Browne RC, editor. Forensic Psychiatry Research

Trends. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2007: 29-62.

20. Bourget D, Gagné P. Maternal filicide in Québec. J Am

Acad Psychiatry Law 2002;30:345-51.

21. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers:

patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry 2007;6:137-41.

22. Flynn SM, Shaw JJ, Abel KM. Filicide: mental illness in

those who kill their children. PLoS One 2013;8:e58981. Crossref

23. Kauppi A, Kumpulainen K, Karkola K, Vanamo T,

Merikanto J. Maternal and paternal filicides: a retrospective

review of filicides in Finland. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law

2010;38:229-38.

24. Legislation.gov.uk. Infanticide Act 1938. Available from:

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/1-2/36. Accessed 25 Mar 2025.

25. Oberman M. Mothers who kill: coming to terms with

modern American infanticide. Am Crim L Rev 1996;34:1-110.

26. Hong Kong SAR Government. Criminal Procedure

Ordinance (Cap 221). Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap221. Accessed 17 Mar 2025.

27. Hong Kong SAR Government. Mental Health Ordinance

(Cap 136). Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap136. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

28. Hong Kong SAR Government. Offences against the

Person Ordinance (Cap 212). Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap212. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

29. Hong Kong Police Force. Crime statistics comparison.

2017. Available from: https://www.police.gov.hk/ppp_en/09_statistics/csc.html. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

30. Child Fatality Review Panel, Social Welfare Department,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Second report for child

death cases in 2010-2011. July 2015. Available from:

https://www.swd.gov.hk/storage/asset/section/655/en/fcw/CFRP2R-Eng.pdf. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

31. Jung K, Kim H, Lee E, et al. Cluster analysis of child homicide

in South Korea. Child Abuse Negl 2020;101:104322. Crossref

32. Lassi N. A Confucian theory of crime [dissertation].

University of North Dakota; 2018.

33. Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LR,

van IJzendoorn MH. The prevalence of child maltreatment

across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child

Abuse Rev 2015;24:37-50. Crossref

34. Lam LC, Wong CS, Wang MJ, et al. Prevalence, psychosocial

correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety

disorders in Hong Kong: the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity

Survey (HKMMS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

2015;50:1379-88. Crossref

35. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality,

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, US Department of Health and Human

Services. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug

Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. November

2014. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHmhfr2013/NSDUHmhfr2013.pdf. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

36. The Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research

and Prevention, The University of Hong Kong. Statistics

of suicide data in Hong Kong (by year). Distribution

of method of suicide by age group in Hong Kong. 2020.

Available from: https://www.csrp.hku.hk/statistics/. Accessed 6 Apr 2023.

37. Chang SS, Chen YY, Yip PS, Lee WJ, Hagihara A, Gunnell D.

Regional changes in charcoal-burning suicide rates in East/

Southeast Asia from 1995 to 2011: a time trend analysis.

PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001622. Crossref

38. Porter T, Gavin H. Infanticide and neonaticide: a review

of 40 years of research literature on incidence and causes.

Trauma Violence Abuse 2010;11:99-112. Crossref

39. Education Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Comprehensive Child Development Service. 2021.

Available from: https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/edu-system/preprimary-kindergarten/comprehensive-child-development-service/index.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2025.