© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

A vintage childhood vaccination card

SK Chuang, FHKAM (Community Medicine)

Guest Author, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

Consultant Community Medicine (Family and Student Health), Family and Student Health Branch, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR, China

Hong Kong’s childhood immunisation programme is

crucial for reducing infant mortality and controlling

many once-common childhood diseases. In 1948,

Hong Kong’s government implemented a free

childhood immunisation programme against

tuberculosis (the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

[BCG] vaccine), diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis.1

Following the opening of new Maternal and Child

Health Centres in the 1950s,2 greater vaccine

research and the World Health Organization’s

approval of new vaccines, further immunisations,

such as those protecting against poliomyelitis (polio)

and measles, were included in the 1960s.1

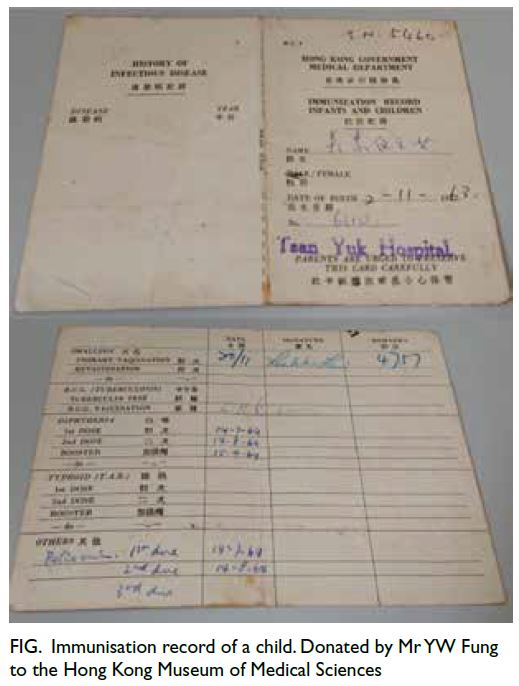

This immunisation record shown in the Figure

was issued by Tsan Yuk Hospital to a girl born there

in 1963. It documents the various vaccines the girl

received as a child. According to this record, she

received the BCG vaccine a few days after birth; the

smallpox vaccine within her first month; two doses

of the polio vaccine, 1 month apart, at about 8 and 9

months old and three doses of the diphtheria vaccine

at 8, 9 and 10 months old. There is no indication that she received the typhoid, paratyphoid A and

paratyphoid B (TAB) vaccine though this was offered

to school children and the public at that time.3

Figure. Immunisation record of a child. Donated by Mr YW Fung to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

General infant vaccination has successfully

eradicated smallpox worldwide. In 1890, Hong

Kong’s Vaccination Ordinance was enacted, legally

requiring all infants to be vaccinated against smallpox

before the age of 6 months.4 The 1923 Vaccine

Ordinance further mandated that every child born

or brought into the territory had to be vaccinated

against the disease within a specified period.5 Yet

in spite of this legal requirement, the initial public

response was poor because many Chinese people

believed that a child should experience two Chinese

New Years before receiving vaccinations.6 In 1946,

postwar Hong Kong experienced almost 2000

smallpox cases,7 but thanks to extensive vaccination

campaigns, the disease was gradually wiped out.

The last recorded case occurred in 1952,8 and Hong

Kong was declared smallpox-free in 1979.7 On 8

May 1980, the World Health Assembly announced

that the disease had been eradicated globally and

recommended countries cease vaccination.9 Hong

Kong removed the smallpox vaccine from its

required childhood immunisation programme in

1981.7

Following smallpox, polio is on course to be the

second infectious disease eradicated worldwide.10

An oral polio vaccine, comprising three types of

virus (types 1, 2 and 3), was added to Hong Kong’s

childhood immunisation programme in 196311 and

was replaced with an inactive viral vaccine in 2007,

which was less likely to cause complications.12 Before

the implementation of vaccination, Hong Kong had

200 to 300 polio cases per year.13 After, the incidence

of polio dramatically reduced7 to the point that Hong

Kong was declared polio-free in 2000.14 However,

due to low vaccination rates in other corners of the

world, the disease has yet to be fully eradicated.10

Another vaccine, the BCG protecting against

tuberculosis, was developed in 1927 and introduced

into Hong Kong’s immunisation programme in

1952 with the assistance of the United Nations

International Children’s Emergency Fund and

the World Health Organization.15 Initially, a mass

vaccination campaign focused on young people

aged <15 years and newborn babies. Subsequently,

newborns were routinely immunised and primary

school children were revaccinated if they failed to react to the tuberculin skin test.16 However,

the revaccination programme was discontinued

from the school year 2000/2001 onwards based

on the available scientific evidence.17 Currently,

only the BCG is administered at birth. Since the

BCG’s introduction, both the notification rate of

tuberculosis and infant mortality from the disease

have steadily declined.7

The first vaccine against diphtheria was

developed in the 1920s.15 Nonetheless, Hong Kong

experienced around 200 cases of this bacterial

infection, half of which proved fatal, annually

between 1928 and 1940.7 Indeed, the incidence of

diphtheria notably increased after the Second World

War,18 peaking in 1959 with an excess of 2000 cases

despite the availability of free immunisation at infant

welfare centres, public dispensaries, hospitals and

schools prior to 1952, and free annual immunisation

campaigns targeting children aged between 6

months and 10 years from 1952 onwards.18 A

major breakthrough in the battle against diphtheria

occurred in 1959 when the immunisation campaign

adopted a house-to-house approach to ensure no

children were overlooked.7 Consequently, the number

of diphtheria cases has fallen drastically since 1960,

and the last fatal case was reported in 1982.7

Enteric fevers (typhoid and paratyphoid) are

life-threatening infections spread by contaminated

food or water. The first vaccine against Salmonella

typhi was developed in 1896 and became widely

used from 1911.19 The TAB vaccine was produced

locally in Hong Kong by the then Bacteriological

Institute as early as 192016 20 and later by the

Institute of Immunology.7 During the early 1950s,

the disease was prevalent in the territory, with

>1000 cases annually. The TAB vaccine was offered

to the public throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and annual campaigns, preceded by publicity, intensified

between May and July.21 22 23 As a result, the number of

cases decreased substantially.8 Following the World

Health Organization’s advice, in 1981, the TAB

vaccine was replaced by the monovalent typhoid

vaccine and was only indicated for individuals

deemed high risk, such as those who lived with a

typhoid carrier or who were travelling to specific

areas.7 Currently, with the improvement in general

hygiene in Hong Kong, typhoid vaccines are only

required for those visiting other areas where typhoid

is endemic, particularly long-stay travellers and

those visiting rural regions where food and beverage

choices may be limited.24

Since the childhood immunisation

programme’s inception, other vaccines, such as those

against rubella, mumps, hepatitis B, chickenpox

and human papillomavirus, have been added.25 The

programme has consistently achieved high coverage

rates of >95% for various vaccines in preschool

children.26

Since 1992, the Advisory Committee on

Immunisation, comprising immunology and public

health experts, set up under the Department of

Health has reviewed Hong Kong’s immunisation

strategy and advised the Director of Health regarding

the childhood immunisation programme.27 This was

replaced when the Centre for Health Protection—under the Director of Health—was established in

2004,28 and the Scientific Committee on Vaccine

Preventable Diseases assumed the role of the

Advisory Committee on Immunisation.29

Nowadays, digital vaccination records stored

and accessed via the eHealth mobile app have

replaced physical immunisation record cards,

thereby saving the trouble of handling paper records

and avoiding losing this vital information.30

References

1. Chan-Yeung MM. A Medical History of Hong Kong: 1942-2015. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 2019: 42. Crossref

2. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. 80th Anniversary Family Health Service 2012. 2013:13. Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/archive/files/reports/DH_booklet_18-7-2013.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2024.

3. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Annual Departmental Report, 1963-1964. Available

from: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/r2081p212#?c=&m=&s=&cv=32&xywh=119%2C2148%2C1024%

2C405. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

4. Historical Laws of Hong Kong Online. Vaccination Ordinance, 1890. Available from: https://oelawhk.lib.hku.hk/items/show/653. Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

5. Historical Laws of Hong Kong Online. Vaccination Ordinance, 1923. Available from: https://oelawhk.lib.hku.hk/items/show/1362. Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

6. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Annual Departmental Report, 1936. Available from:

https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/cj82s8120#?c=&m=&s=&cv=217&xywh=79%2C773%2C1612%2C638.

Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

7. Lee SH. Epidemiological surveillance of communicable diseases [MD thesis]. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong; 1991.

8. Chan-Yeung MM. A Medical History of Hong Kong: 1842-1941. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 2018: 215-7. Crossref

9. Shchelkunova GA, Shchelkunov SN. 40 years without smallpox. Acta Naturae 2017;9:4-12. Crossref

10. Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Polio Eradication Strategy 2022-2026. Delivering on a Promise. 2021. Available

from: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Polio-Eradication-Strategy-2022-2026-Delivering-on-a-Promise.pdf. Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

11. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. How Hong Kong defeats

viruses. The chapter on vaccines. Jan 2021. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/how_hong_kong_defeats_viruses_covid19_vaccines.pdf . Accessed 7 Feb 2025.

12. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Updated Childhood Immunisation Programme to launch

in 2007 [press release]. 2006 Dec 13. Available from: https://www.dh.gov.hk/english/press/2006/061213_1.html.

Accessed 2 Jan 2025. Crossref

13. Starling A, Ho FC, Luke L, Tso SC, Yu EC. Plague, SARS and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2006: 51.

14. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Director of Health is proud of Hong Kong being polio-free

[press release]. 2000 Oct 30. Available from: https://www.dh.gov.hk/english/press/2000/00_10_30.html. Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

15. Chan-Yeung MM. A Medical History of Hong Kong: 1842-1941. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 2018: 261. Crossref

16. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Director of Medical and Health Services. Annual Departmental Reports 1953-54: 44-6.

17. Tam CM, Leung CC. Cessation of the BCG (Bacille Calmette Guérin) revaccination programme for primary school

children in Hong Kong. Public Health & Epidemiology Bulletin 2000;9:25-7. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/grp_cessation_of_bcg_revaccination_program_en_2004052100.pdf . Accessed 15 Nov 2024.

18. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Director of Medical and Health Services. Annual Departmental Reports 1953-54: 17-8.

19. Joi P. Vaccine profiles: Typhoid. 2023 Jan 11. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/routine-vaccines-extraordinary-impact-typhoid#:~:text=The%20first%20vaccine%20against%20S,Antibiotics%20became%20available%20in%201948 . Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

20. HH Scott. Report of Bacteriological Institute 1920. Medical and Sanitary Reports for the Year 1920. Available

from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ee/Administrative_Reports_for_the_year_1920%2C_Appendix_M%2C_Medical_and_Sanitary.pdf . Accessed 12 Feb 2025.

21. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Annual Departmental Report 1957-1958.

Available from: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/r2081p20s#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-2837%2C-

148%2C7473%2C2957. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

22. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Annual Departmental Report, 1958-1959. Available

from: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/qv340234j#?c=&m=&s=&cv=29&xywh=112%2C1842%2C1770%

2C700. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

23. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong Government. Annual Departmental Report, 1961-1962. Available from:

https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/tt44wq35c#?c=&m=&s=&cv=38&xywh=-92%2C547%2C1808%2C715.

Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

24. Travel Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Vaccine and prophylaxis. Typhoid

vaccination. 2020 Dec 28. Available from: https://www.travelhealth.gov.hk/english/vaccine_prophylaxis/typhoid.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

25. Family Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Schedule of Hong Kong Childhood

Immunisation Programme. 2024 May 21. Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/main_ser/child_health/child_health_recommend.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

26. World Health Organization. WHO immunisation data portal. Available from: https://immunizationdata.who.int/global?topic=Vaccination-coverage&location=HKG. Accessed 7 Nov 2024.

27. Leung CW. Immunisation. HK J Paediatr (New Series) 1999;4:52-62.

28. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Centre for Health Protection Strategic Plan 2010-2014. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/chp_strategic_plan_2010-2014.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2025.

29. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Scientific Committee on

Vaccine Preventable Diseases. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/24008.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

30. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. School Immunisation Teams.

2024 Sep 6. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/features/102121.html. Accessed 15 Nov 2024.