Hong Kong Med J 2025 Feb;31(1):24–31 | Epub 12 Feb 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Success rate of induction of labour in twin pregnancies relative to singleton pregnancies in a predominantly Chinese population

CK Wong, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); Catherine MW Hung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); Vivian KS Ng, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); WK Yung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); WC Leung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); WL Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr CK Wong (wck936@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study assessed the efficacy of

induction of labour in twin pregnancies relative

to singleton pregnancies within a predominantly

Chinese patient population.

Methods: This retrospective case-matched cohort

study included patients with twin pregnancies who

underwent induction of labour at our institution in

Hong Kong between 2012 and 2020. Patients with

twin pregnancies were matched one-to-one with

singleton pregnancies based on parity, maternal

age, and the indication for induction of labour. The

primary outcome was the mode of delivery. Secondary

outcomes included the time from oxytocin infusion

to delivery, indications for caesarean or instrumental

delivery, and maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Results: In total, 160 women with twin pregnancies

met the inclusion criteria and were matched with

160 singleton pregnancies. Caesarean section

was performed in 42 patients (26.3%) with twin

pregnancies and 27 patients (16.9%) with singleton

pregnancies undergoing induction of labour.

Patients with twin pregnancies had a significantly

higher risk of caesarean section relative to those

with singleton pregnancies (odds ratio=2.14, 95%

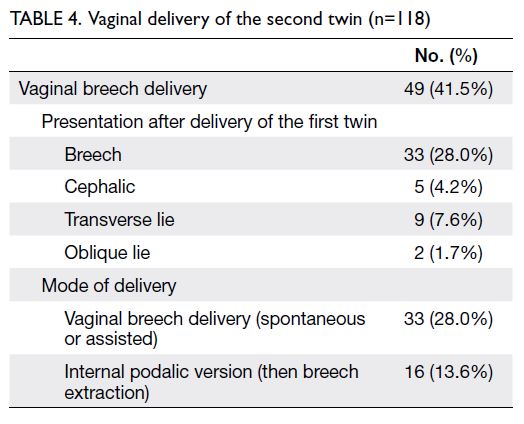

confidence interval=1.14-4.04; P=0.024). Internal podalic version was required in 13.6% of cases for

the vaginal delivery of the second twin. There was no

significant difference between the groups in the time

from oxytocin administration to vaginal delivery

(P=0.143).

Conclusion: Despite a higher induction failure

rate, about three quarters of twin pregnancy

patients achieved successful vaginal deliveries.

Our findings inform decision making for patients

and obstetricians, emphasising the importance of

training for internal podalic version to aid second

twin delivery and reduce caesarean rates in twin

pregnancies.

New knowledge added by this study

- Approximately three-quarters of patients with twin pregnancies who underwent induction of labour achieved successful vaginal deliveries.

- The failure rate of induction of labour was higher in twin pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies.

- The probability of requiring a caesarean section for the second twin when the first twin is delivered vaginally is only 0.8% if experts in twin vaginal delivery are available. Internal podalic version was necessary in 13.6% of cases for the vaginal delivery of the second twin.

- Patients with twin pregnancies undergoing induction of labour should be counselled regarding the increased risk of unsuccessful labour induction relative to singleton pregnancies.

- Proficient obstetricians skilled in internal podalic version should be readily available during the delivery of the second twin to improve the success rate of vaginal delivery for the second twin.

- Greater emphasis should be placed on implementing training opportunities, simulation models, and practices for junior obstetricians to enhance proficiency in internal podalic version. These measures can facilitate second twin delivery and reduce the need for caesarean sections in second twin births.

Introduction

The global twin birth rate has increased by one-third

since the 1980s, rising from 9.1 to 12 per

1000 deliveries, resulting in approximately 1.6

million twin pairs born annually.1 One major factor contributing to this trend is the growing

use of assisted reproductive techniques in recent

decades.1 Relative to singleton pregnancies, twin

pregnancies are associated with higher incidences

of maternal and fetal complications, which may require earlier delivery.2 3 Even in uncomplicated

cases, the National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend delivery

at 37 weeks for dichorionic twin pregnancies and

36 weeks for monochorionic twin pregnancies.4

Consequently, earlier delivery is frequently required

in twin pregnancies. The Twin Birth Study,5 a large

multicentre randomised controlled trial published

in 2013, demonstrated the safety of both vaginal and

caesarean birth in twin pregnancies where the first

twin presented in cephalic position at 32 weeks of

gestation or later. These findings have supported an

increase in vaginal deliveries for twin pregnancies

through induction of labour.

The success rate, benefits, and complications

associated with induction of labour in singleton

pregnancies have been extensively studied.6 7

However, only a limited number of studies have

compared the success rate of induction of labour in

twin pregnancies relative to singleton pregnancies.8 9 10 11

According to Loscul et al8 and Okby et al,9 induction

of labour in twin pregnancies increases the likelihood

of caesarean section. In contrast, Fausett et al10 and

Taylor et al11 reported that the risk of caesarean delivery in twin pregnancies is comparable to the

risk in singleton pregnancies undergoing induction

of labour. These conflicting findings may arise from

variations in induction methods, ethnicity-related

factors, selection biases, and differences in study

designs.

To provide appropriate counselling to patients, obstetricians must understand the likelihood of

vaginal delivery after induction of labour. Reliance

on data from singleton deliveries to estimate this

likelihood for twin pregnancies may be inappropriate

due to inherent differences between twin and

singleton pregnancies.12 Considering the current

lack of robust evidence regarding induction of labour

in twin pregnancies, this study aimed to evaluate

the rate of caesarean section (including classical or

lower segment caesarean sections) and associated

outcomes in twin pregnancies undergoing induction

of labour, compared with singleton pregnancies.

Methods

Study design

Our institution, a regional public hospital in Hong

Kong, provides obstetric services for 3000 to 5000

deliveries annually. All cases of twin pregnancies are

recorded in a specialised twin pregnancy clinic registry

and managed by a dedicated team of obstetricians

and midwives in the Twin Pregnancy Clinic. The

medical professionals overseeing this clinic have

specialised expertise in maternal fetal medicine.13

In accordance with departmental protocol, patients

attend regular follow-up appointments and

undergo ultrasound examinations. When a patient

approaches term or requires earlier delivery, the

attending obstetrician discusses the mode of delivery

with the patient. For uncomplicated dichorionic-diamniotic

and monochorionic-diamniotic twin

pregnancies, vaginal delivery is encouraged if the

first twin presents in cephalic position.

The same induction of labour protocol is

applied to both twin and singleton pregnancies.

Patients are admitted to the hospital and a cervical

examination is conducted to assess the modified

Bishop score. If the cervix is unfavourable with a

modified Bishop score (Calder score) <6, cervical

priming is performed using either dinoprostone

tablets or a cervical ripening balloon (Cook Medical,

Bloomington [IN], United States). If the cervix

is favourable with a modified Bishop score ≥6,

the patient is transferred to the labour ward for

artificial rupture of membranes and administration

of synthetic oxytocin. The induction of labour

protocol used in this study aligns with NICE

recommendations, except that the modified Bishop

score was used instead of the Bishop score to assess

cervical readiness for induction.14 15

Medical records of patients with twin

pregnancies who underwent induction of labour

and delivered at our institution between January

2012 and December 2020 were retrospectively

identified using the International Classification of

Diseases codes through the Clinical Data Analysis

and Reporting System of Hospital Authority.

The identified medical records were individually

reviewed. Study participants were required to meet all of the following inclusion criteria: gestational

age ≥24 weeks, intact membranes, and planned

induction of labour. Exclusion criteria included

premature rupture of membranes, labour in the

latent or active phase, threatened preterm labour

resulting in spontaneous labour, and intrauterine

fetal death.

Each twin pregnancy patient who underwent

induction of labour was matched with a singleton

pregnancy patient at a 1:1 ratio in the same hospital

during the same study period. Matching was based

on specific criteria, including parity (nulliparous or

multiparous),16 maternal age (advanced maternal

age of ≥35 years, or not),16 17 and the indication for

induction of labour.18 These criteria were selected to

minimise confounding factors that could affect the

success rate of induction of labour. To further reduce

the impact of variations in medical practice during

the study period, the singleton pregnancy patient

with the delivery date closest to that of the twin

pregnancy patient was selected.

For both twin and singleton pregnancies,

demographic data, past obstetric history, parity,

modified Bishop score, method of cervical priming,

indication for induction of labour, and use of epidural

analgesia were recorded. The primary outcome was

the mode of delivery. Secondary outcomes included

the time from oxytocin infusion to vaginal delivery or

caesarean section, indications for caesarean section

or instrumental delivery, and maternal and neonatal

outcomes. Postpartum haemorrhage was defined

as blood loss of ≥500 mL, regardless of the mode of

delivery. Patients who underwent caesarean section

for the second twin after vaginal delivery of the first

twin were considered to have undergone caesarean

section.

Statistical analyses

To calculate the required sample size, it was assumed

that the incidences of caesarean section were 25%

in the control group and 40% in the study group.

The proportion of discordant pairs was assumed

to be 0.45. A two-sided significance level of 0.05

was selected, and the study aimed to achieve a 1:1

comparison between the groups. Calculations in

G*Power software (version 3.1.9.6; Erdfelder, Faul,

& Buchner, Germany) indicated that a total sample

size of 160 pairs would provide 80% power for the

analysis.

Categorical variables are reported as numerator

and denominator values (%), whereas continuous

variables are presented as mean±standard deviation.

McNemar’s test was used to analyse the primary

outcome for twin pregnancies and their matched

controls. Data for the matched pairs are presented

in a 2×2 table, showing concordant and discordant

study pairs. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated as the

ratio of discordant pairs, and the test statistic was derived from McNemar’s test. For the remaining

outcomes, paired t tests, Wilcoxon signed rank

test and analyses of variance were used to analyse

continuous variables, whereas McNemar’s tests

or Fisher’s exact tests were utilised for categorical

variables when comparing the case and control

groups. For non-matched data, the Chi squared test

was applied for categorical data, and unpaired t tests

were used for normally distributed continuous data.

Statistical analyses of data using McNemar’s

test were performed with Epi Info (version 7.2.5.0;

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

[GA], US). All other analyses were conducted with

SPSS (Windows version 27.0; IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], US). Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 760 women with twin

pregnancies were recorded out of 42 280 maternity

cases. Of these, 160 women met the inclusion criteria

for this study. The incidence of twin pregnancies

was 1.8% and the rate of induction of labour in twin

pregnancies was 21.1%.

The study group consisted of women with twin

pregnancies who underwent induction of labour,

whereas the control group comprised women with

singleton pregnancies who delivered at the same

hospital during the same period. The two groups

were matched in terms of age, parity and indication

for induction of labour, and were well balanced with

respect to these matching factors. Patients with

twin pregnancies had a significantly lower body

mass index (21.1 kg/m2 vs 22.2 kg/m2; P=0.008) and

a significantly higher modified Bishop score (6.2

vs 5.4; P<0.001) relative to the control group. The

mean gestational age at delivery was significantly

earlier in twin pregnancies than in the control group

(37.1 weeks vs 40.2 weeks; P<0.001). Other baseline

characteristics, including ethnicity, prior caesarean

section, and use of epidural anaesthesia, did not

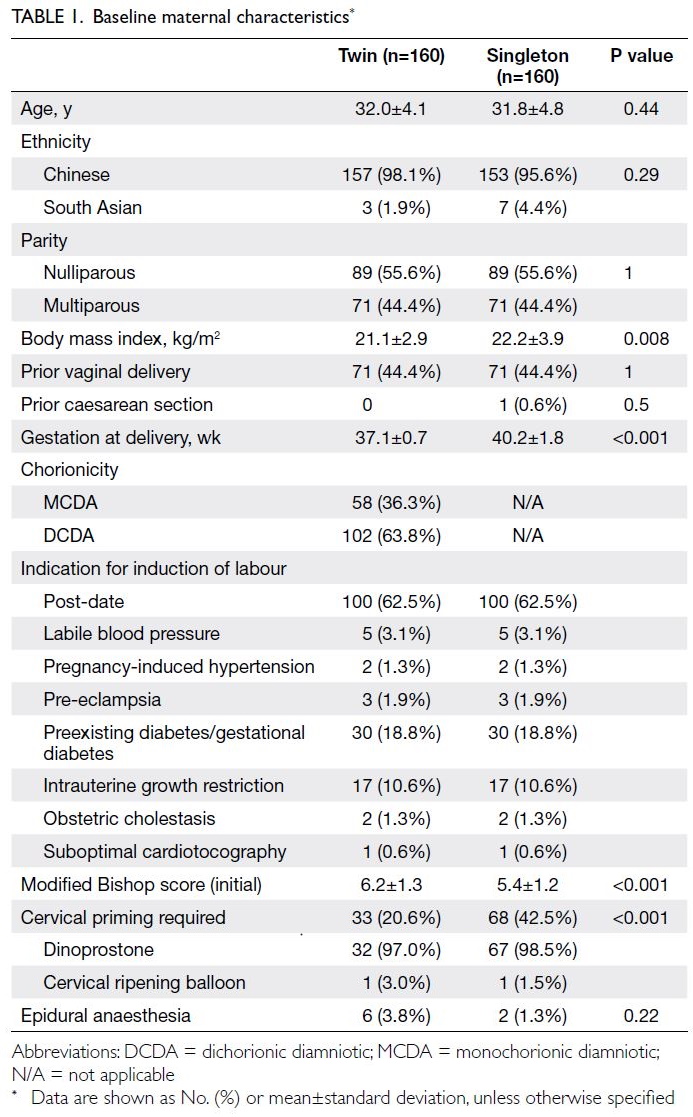

significantly differ between the two groups (Table 1).

Success rate of induction of labour

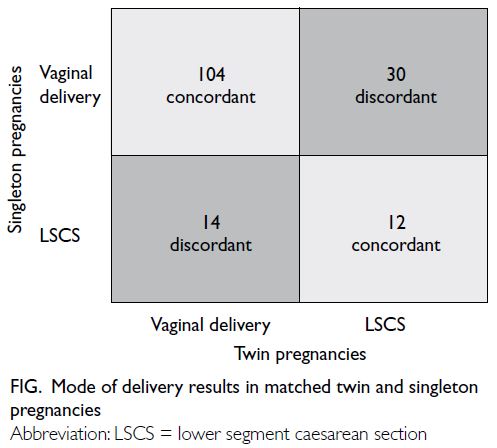

Out of 160 pairs, 44 were discordant (ie, one member

of the pair had a caesarean section and the other

had a vaginal delivery), and 116 were concordant

(ie, both members of the pair had either a caesarean

section or a vaginal delivery) [Fig]. Patients with

twin pregnancies who underwent induction of

labour had a significantly higher risk of caesarean

section relative to those with singleton pregnancies

(OR=2.14, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.14-4.04;

P=0.024).

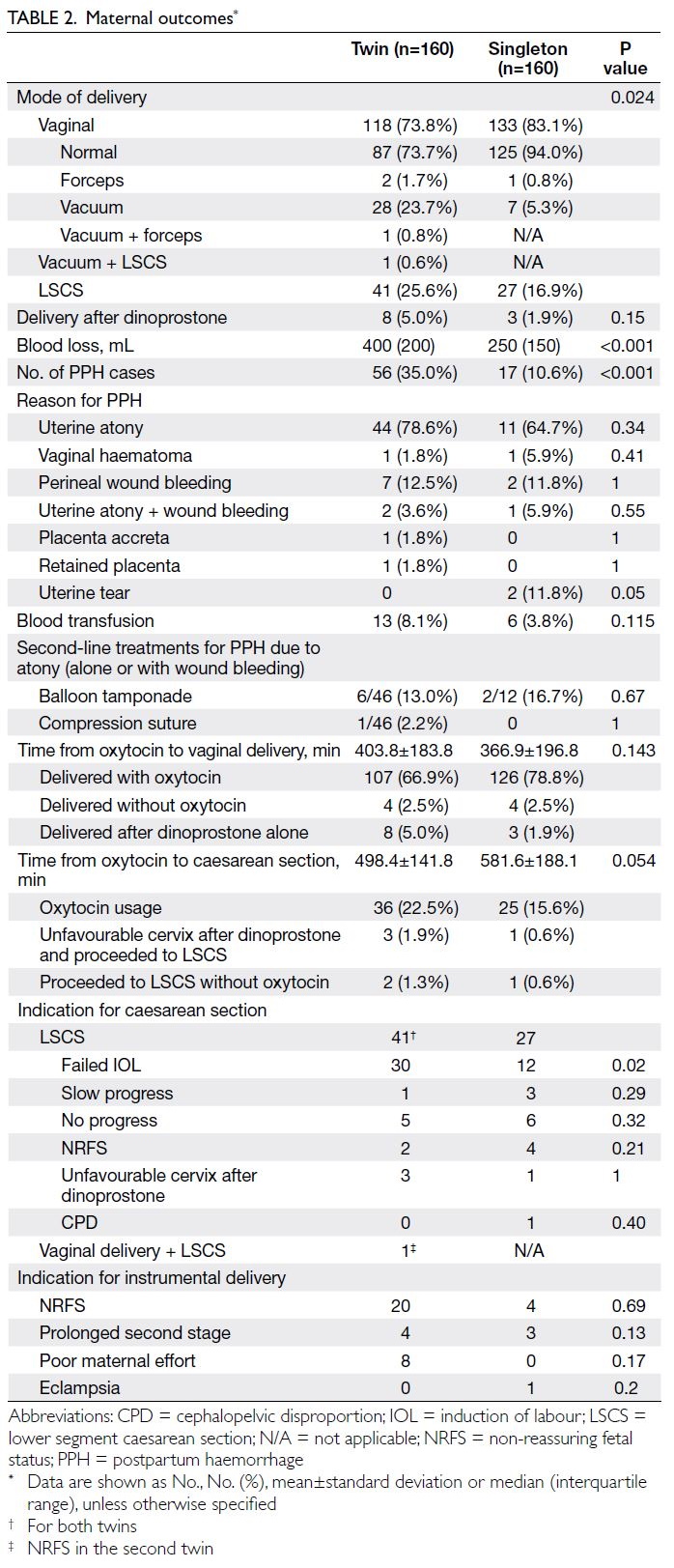

Among the patients with twin pregnancies,

there were 118 vaginal deliveries, 41 caesarean

sections, and one case in which the first twin

was delivered vaginally and the second twin was delivered by caesarean section. Among the patients

with singleton pregnancies, there were 133 vaginal

deliveries and 27 caesarean sections. Instrumental

deliveries were performed in 32 patients with twin

pregnancies and eight patients with singleton

pregnancies (Table 2).

There was no significant difference between the

groups in the time from oxytocin administration to

vaginal delivery (P=0.143) or the time from oxytocin

administration to caesarean section (P=0.054). In

total, eight patients with twin pregnancies and three

patients with singleton pregnancies delivered after

dinoprostone insertion without requiring artificial

rupture of membranes or oxytocin infusion. Three

patients with twin pregnancies and one patient with a singleton pregnancy had an unfavourable cervix

after repeated doses of dinoprostone; thus, caesarean

section was performed (Table 2).

Obstetric outcomes

Twin pregnancies were associated with significantly

greater blood loss relative to singleton pregnancies

(median: 400 mL vs 250 mL; P<0.001) and a higher

incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (35.0% vs

10.6%; P<0.001). However, there was no significant

difference between the groups in blood transfusion

rates (8.1% vs 3.8%; P=0.115). The aetiology of

postpartum haemorrhage and need for second-line

treatments were also comparable between the two

groups (Table 2).

Mode of delivery in twin pregnancies

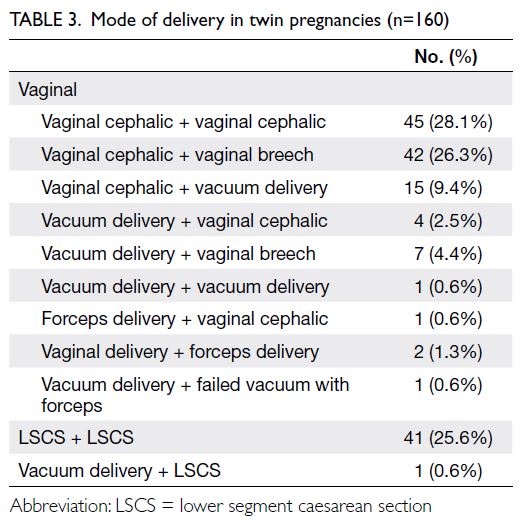

Among those 118 vaginal deliveries, 45 had vaginal

cephalic deliveries of both twins, whereas 42 had a

vaginal cephalic delivery of the first twin followed

by a vaginal breech delivery of the second twin.

Additionally, 32 patients required instrumental

delivery with vacuum or forceps for at least one twin

(Table 3).

In cases where vaginal breech delivery was

required for the second twin, most babies were in

breech presentation. Internal podalic version was

performed in 16 patients (13.6%) to facilitate delivery

of the second twin (Tables 3 and 4). Notably, even

in five cases where the second twin was in cephalic

presentation, internal podalic version was performed

by manual upward displacement of the fetal head to

expedite delivery due to fetal bradycardia or cord

presentation.

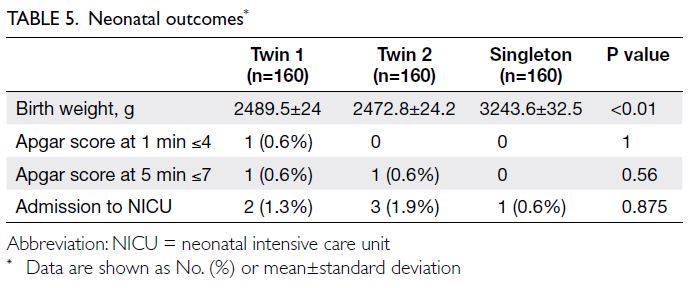

Neonatal outcomes

When neonatal outcomes were compared between the two groups, no significant differences were

observed in Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes or in

rates of admission to neonatal intensive care units.

However, both the first and second twins were

significantly lighter in weight relative to neonates in

singleton pregnancies (Table 5).

Discussion

Primary outcomes

This case-control study, utilising matched controls,

demonstrated that the rate of failed induction of

labour was significantly higher in twin pregnancies

than in singleton pregnancies. Nevertheless, 73.8% of

patients with twin pregnancies achieved successful

vaginal deliveries. This study represents the largest

cohort investigation of its kind in a predominantly

Chinese population and differs from previous studies

conducted in Western countries.8 9 10 11 A previous

study19 revealed that ethnic variation can influence

the success of induction of labour; thus, our findings

provide valuable insights for counselling and

managing Chinese patients with twin pregnancies.

Comparison with previous studies

The literature on induction of labour in twin

pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies

remains limited. The present findings are consistent

with those reported by Loscul et al8 and Okby et al,9

both of which identified an increased risk of caesarean

delivery after induction of labour in twin pregnancies.

Loscul et al8 reported an adjusted OR of 1.8 (95%

CI=1.4-2.2), whereas Okby et al9 reported an adjusted

OR of 2.2 (95% CI=1.7-2.7). Similarly, the current

study demonstrated an OR of 2.14, reinforcing the

notion that induction of labour in twin pregnancies

is associated with a higher rate of caesarean

section relative to singleton pregnancies. However,

limitations existed in these studies. For instance, the

large cohort study by Loscul et al,8 which included

1995 twin deliveries and 2771 singleton deliveries,

did not consider chorionicity, and the methods

of induction were not described; considering the

multicentre retrospective design of that study,

interhospital variations may have existed in terms

of induction methods, intrapartum assessment, and

decisions regarding caesarean section. Furthermore,

Okby et al9 included 191 twin deliveries and 25 913

singleton deliveries, but did not provide details

regarding induction methods, cervical status prior to

induction, Bishop score, or the chorionicity of twin

pregnancies. Conversely, Fausett et al10 and Taylor

et al11 included smaller cohorts of twin pregnancies

(62 and 100 patients, respectively), and their findings

may have been influenced by the small sample sizes.

The method of random patient selection used in the

control group of the study by Taylor et al11 may have

introduced potential bias. Another factor potentially contributing to differences in findings among these studies is ethnic variation.

Physiological explanations

Physiological differences in the myometrium between twin and singleton pregnancies may explain the higher incidence of failed labour induction in twin

pregnancies. Research has shown that myometrial

activity in twin pregnancies is characterised by

shorter and more frequent contractions compared

with singleton pregnancies, particularly at term.20

Shortened contraction duration may result

in ineffective and dysfunctional contractions,

increasing the likelihood of failed labour induction.

Additionally, the uterus undergoes greater distension

and stretching in twin pregnancies. Physiological

studies have indicated that increased myometrial

stretching is associated with reduced uterine

contraction in response to oxytocin stimulation.21

One potential mechanism for this phenomenon is

that prolonged stretching enhances the expression

or activity of TWIK-related K+ channels, which

subsequently diminish myometrial contraction in

response to oxytocin.21 Further physiological and

molecular investigations are warranted to explore the

differences between singleton and twin pregnancies

in greater detail.

Clinical implications of secondary outcomes

In conjunction with the primary outcomes, the

secondary outcomes of this study provide important

clinical insights and have substantial implications.

Notably, 26.3% of twin pregnancies delivering

vaginally required a vaginal breech delivery for

the second twin (Tables 3 and 4). Therefore, we

recommend that senior obstetricians with expertise

in internal podalic version and breech extraction be

present during such deliveries.

This study identified one patient who required

a caesarean section for the second twin after the

first twin had been delivered vaginally. When the

first twin was delivered vaginally in our cohort,

the probability of caesarean section for the second

twin was 0.8%. Patients should be informed of this

potential risk prior to induction of labour. Previous

studies have shown that the risk of caesarean

section for the second twin after vaginal delivery

of the first twin ranges from 4.3% to 10.7%.5 22 23 24 In

our cohort, the percentage of caesarean deliveries

for second twins was much lower than that in

other series, including another retrospective study

conducted in Hong Kong with the same ethnic

population.22 23 24 This discrepancy may be attributed

to selection bias because the present study included

only patients undergoing induction of labour,

whereas other studies included patients with both

induction of labour and spontaneous onset of

labour. Furthermore, elective induction of labour for

twin pregnancies in our unit is typically scheduled

during daytime hours. This practice ensures the

availability of experienced staff proficient in internal

podalic version, potentially improving the likelihood

of successful vaginal delivery for the second twin.

Our findings showed that 13.6% of cases involving second twin deliveries required internal podalic

version, primarily due to transverse or oblique lie

(Table 4). Even when the second twin presented in

cephalic position (as observed in five cases), internal

podalic version was required to expedite delivery

because of complications such as cord presentation

or fetal bradycardia. The presence of experienced

staff skilled in performing internal podalic version

can significantly increase the likelihood of achieving

successful vaginal delivery for the second twin. At

our hospital, vaginal twin deliveries during daytime

hours are typically supervised by experienced

obstetric consultants or associate consultants.

Strengths and limitations

To minimise the impact of variations in medical

practice during the study period, we utilised a

rigorous matching approach in which the singleton

pregnancy patient with the delivery date closest to

that of the twin pregnancy patient was selected.

This approach effectively reduced the potential for

confounding factors, including variations in medical

practices, and ensured that the same induction of

labour protocol was applied to both patient groups.

Also, we recorded detailed information concerning

chorionicity, indications for induction of labour, and

the modified Bishop score. Finally, the induction of

labour protocol used in this study aligns with NICE

recommendations; thus, the results are applicable to

other centres that use a similar protocol.

However, this study had some limitations.

The earlier gestational age at delivery in the twin

pregnancy group, as recommended by international

guidelines4 even for uncomplicated twin pregnancies,

may have affected the efficacy of induction of labour

and influenced the overall outcomes. Additionally,

patients with twin pregnancies had a higher initial

modified Bishop score relative to those with

singleton pregnancies. This difference may be due to

selection bias because obstetricians often discourage

vaginal delivery in patients with low initial modified

Bishop scores; instead, they recommend caesarean

section. Despite the higher initial modified Bishop

score in twin pregnancies, the success rate of vaginal

delivery remained lower in this group than in

singleton pregnancies, suggesting that this factor did

not significantly influence the study’s results.

Although the induction of labour protocol was

consistent for both twin and singleton pregnancies,

variations in obstetricians’ assessments of cervical

dilatation, labour progression, and confidence in

managing vaginal twin deliveries may have influenced

study outcomes. Obstetricians with less experience

or confidence in vaginal twin delivery may have been

more likely to diagnose failed induction of labour

and proceed with caesarean section. However, no

statistically significant difference was observed in

the time from initiation of oxytocin to selection of caesarean section between the two groups.

The retrospective nature of the study introduced

potential biases, and the limited incidence of twin

pregnancies in a single regional hospital restricted

the sample size. A larger sample size and multicentre

design would enhance the generalisability of the

findings. Furthermore, because the study primarily

included Chinese patients, the applicability of these

conclusions to other ethnic groups is limited; there

is a need for further research in this area.

Conclusion

The failure rate of induction of labour was higher

in twin pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies.

Nevertheless, 73.8% of patients with twin

pregnancies achieved successful vaginal deliveries;

approximately 20% required instrumental delivery

for at least one twin. Furthermore, twin pregnancies

were associated with a higher incidence of

postpartum haemorrhage. These findings can help

facilitate informed decision making for patients and

obstetricians when considering induction of labour

and selecting the most appropriate mode of delivery

for patients with twin pregnancies.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CK Wong, WL Lau.

Acquisition of data: CK Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CK Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: CK Wong, CMW Hung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: CK Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CK Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: CK Wong, CMW Hung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Kwong Wah Hospital Clinical Research

Centre and Mr Steven Lau, Biostatistician from the Centre for

Clinical Research and Biostatistics of The Chinese University

of Hong Kong, for their statistical advice.

Declaration

This work was posted on Authorea as a registered online

preprint (https://doi.org/10.22541/au.169320065.53300017/v1).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Kowloon Central Cluster/Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: KC/KE-22-0113/ER-3). The requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the

Committee due to the retrospective nature of the research

and the use of anonymised data in the research.

References

1. Monden C, Pison G, Smits J. Twin peaks: more twinning

in humans than ever before. Hum Reprod 2021;36:1666-73. Crossref

2. Santana DS, Cecatti JG, Surita FG, et al. Twin pregnancy and

severe maternal outcomes: the World Health Organization

multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health.

Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:631-41. Crossref

3. Cheong-See F, Schuit E, Arroyo-Manzano D, et al.

Prospective risk of stillbirth and neonatal complications

in twin pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ 2016;354:i4353. Crossref

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE

guideline [NG137]. Twin and triplet pregnancy. London:

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2019.

5. Barrett JF, Hannah ME, Hutton EK, et al. A randomized

trial of planned cesarean or vaginal delivery for twin

pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1295-305. Crossref

6. Sotiriadis A, Petousis S, Thilaganathan B, et al. Maternal

and perinatal outcomes after elective induction of labor at

39 weeks in uncomplicated singleton pregnancy: a meta-analysis.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53:26-35. Crossref

7. Stock SJ, Ferguson E, Duffy A, Ford I, Chalmers J,

Norman JE. Outcomes of elective induction of labour

compared with expectant management: population-based

study. BMJ 2012;344:e2838. Crossref

8. Loscul C, Schmitz T, Blanc-Petitjean P, Goffinet F, Le

Ray C; JUMODA and MEDIP study groups. Risk of

cesarean after induction of labor in twin compared to

singleton pregnancies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

2019;237:68-73. Crossref

9. Okby R, Shoham-Vardi I, Ruslan S, Sheiner E. Is induction

of labor risky for twins compare to singleton pregnancies?

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:1804-6. Crossref

10. Fausett MB, Barth WH Jr, Yoder BA, Satin AJ. Oxytocin

labor stimulation of twin gestations: effective and efficient.

Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:202-4. Crossref

11. Taylor M, Rebarber A, Saltzman DH, Klauser CK, Roman AS,

Fox NS. Induction of labor in twin compared with singleton

pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:297-301. Crossref

12. Amikam U, Hiersch L, Barrett J, Melamed N. Labour induction in twin pregnancies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2022;79:55-69. Crossref

13. Yung WK, Liu AL, Lai SF, et al. A specialised twin pregnancy

clinic in a public hospital. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet

Midwifery 2012;12:21-32.

14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE

guideline [NG207]. Inducing labour. London: National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2021.

15. Thomas J, Kavanagh J, Kelly A, editors. RCOG Evidence-based Clinical Guidelines Induction of labour. RCOG Press; 2001.

16. Batinelli L, Serafini A, Nante N, Petraglia F, Severi FM,

Messina G. Induction of labour: clinical predictive factors

for success and failure. J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;38:352-8. Crossref

17. Jeong Y, Choo SP, Yun J, Kim EH. Effect of maternal age

on maternal and perinatal outcomes including cesarean

delivery following induction of labor in uncomplicated

elderly primigravidae. Medicine (Baltimore)

2021;100:e27063. Crossref

18. Chan YY, Lo TK, Yu EL, Ho LF. Indications for induction

of labour and mode of delivery in nulliparous term women

with an unfavourable cervix. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet

Midwifery 2021;21:69-75. Crossref

19. Papoutsis D, Antonakou A, Tzavara C. The effect of ethnic

variation on the success of induced labour in nulliparous

women with postdates pregnancies. Scientifica (Cairo)

2016;2016:9569725. Crossref

20. Turton P, Arrowsmith S, Prescott J, et al. A comparison of

the contractile properties of myometrium from singleton

and twin pregnancies. PLoS One 2013;8:e63800. Crossref

21. Yin Z, He W, Li Y, et al. Adaptive reduction of human

myometrium contractile activity in response to prolonged

uterine stretch during term and twin pregnancy. Role of

TREK-1 channel. Biochem Pharmacol 2018;152:252-63. Crossref

22. Mok SL, Lo TK. Vaginal delivery of second twins: factors

predictive of failure and adverse perinatal outcomes. Hong

Kong Med J 2022;28:376-82. Crossref

23. Tang HT, Liu AL, Chan SY, et al. Twin pregnancy outcomes

after increasing rate of vaginal twin delivery: retrospective

cohort study in a Hong Kong regional obstetric unit. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:1094-100. Crossref

24. Kong CW, To WW. The predicting factors and outcomes

of caesarean section of the second twin. J Obstet Gynaecol

2017;37:709-13. Crossref