Hong Kong Med J 2025 Feb;31(1):9–11 | Epub 7 Feb 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

Clinical errors and mistakes: civil or criminal

liability?

Albert Lee, MD, LLM1,2,3,4; Monique A Anawis, MD5; JD, Roy G Beran, MD, FRACP6,7,8; Tracy Cheung, LLB, PCLL9,10; Calvin Ho, LLM, JSD2,11; Hwan Kim, LLM, CPCU12

1 Emeritus Professor, The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Centre for Medical Ethics and Law, Faculties of Law and Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Adjunct Professor, International Centre for Future Health System, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

4 Vice President (Asia), World Association for Medical Law, United States

5 Clinical Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, United States

6 Conjoint Professor, South Western Sydney Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

7 Conjoint Professor, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

8 Professor, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia

9 Consultant, Wanda Tong & Co, Hong Kong SAR, China

10 Lecturer, School of Law, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

11 Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

12 Senior Vice President, Healthcare Division (Asia Pacific), Allied World Assurance Company

Corresponding author: Dr Albert Lee (alee@cuhk.edu.hk); Ms Tracy Cheung (tracycheung@bosc.com.hk)

Civil liability of doctors arises when there is a

clinically negligent act or omission resulting in harm

as a consequence of a doctor not meeting the standard

of care as expected from reasonable medical practice

or failure to warn.1 Do clinical errors and mistakes

necessarily equate to negligence? The essential

elements required to establish negligence, are: (1)

the existence of a duty of care owed to the patient;

(2) a breach of duty as determined by standard of

care; (3) the patient has experienced harm; and (4) a

causal connection, between the defendant’s careless

act and the resulting damage incurred with the

damage considered foreseeable and not too remote.2

In Hatcher v Black,3 Lord Denning explained a case

that a woman P, who suffered side-effects from

an operation on her throat and sued the surgeon

concerned. Denning J stated that:

“…on the road or in a factory there ought not to be any accidents if everyone used proper care, but in a hospital there was always a risk. It would be disastrous to the community if a doctor examining a patient or operating at the table, instead of getting on with his work, were forever looking over his shoulder to see if someone was coming up with a dagger. The jury should not find the defendant negligent simply because one of the risks inherent in an operation actually took place, or because in a matter of opinion he made an error of judgement. They should find him liable only if he had fallen short of the standard of medical care, so that he was deserving of censure…”

(The jury found in favour of the defendant).

“…on the road or in a factory there ought not to be any accidents if everyone used proper care, but in a hospital there was always a risk. It would be disastrous to the community if a doctor examining a patient or operating at the table, instead of getting on with his work, were forever looking over his shoulder to see if someone was coming up with a dagger. The jury should not find the defendant negligent simply because one of the risks inherent in an operation actually took place, or because in a matter of opinion he made an error of judgement. They should find him liable only if he had fallen short of the standard of medical care, so that he was deserving of censure…”

(The jury found in favour of the defendant).

According to the Bolam test,4 “a doctor will not

be found negligent if he/she has acted in accordance

with a practice accepted as proper by a reasonable body of medical opinion”. It appears unreasonable or

of limited social value to impose a criminal sanction

on a medical practitioner for genuine clinical errors

and mistakes.

The majority of litigation, following alleged

medical malpractice, is brought under the tort of

negligence (civil claims) and the remedy sought is

monetary compensation. Criminalisation of medical

malpractice falls into the realm of retributive justice

which is a system of criminal justice focusing solely

on punishment, rather than deterrence or the

rehabilitation of offenders. The punishment should

be in proportion to the seriousness of the crime

committed.5 The negligent act should be culpable to

constitute a criminal act, such as gross negligence

manslaughter (GNM).6 This raises pertinent issues

and questions in health care, such as: Is criminal

prosecution really promoting patient safety and

safeguarding public interest? Should the focus be

on conduct rather than outcome? Should the use of

restorative justice, emphasising retribution, surpass

deterrence and rehabilitation?7

An expert panel conducted a pre-recorded

seminar, followed by an interactive panel, to analyse

GNM, in the healthcare setting, across different

common law jurisdictions (including Australia,

England, Hong Kong, Singapore and the United

States) in November 2021.8 A paper is under

preparation which reports the critical points of those

presentations, together with further analyses of cases

and literature in jurisdictions adopting common law,

to provide a better understanding of how clinical

negligence might lead to criminal proceedings.

This editorial aims to recap the English case of Bawa-Garba,9 to discuss the factors to be taken

into consideration for medical crime. There were a

number of high-profile criminal investigations and

prosecutions of healthcare professionals (HCPs)

in England, with no offence recorded in Scotland

and only 14 HCPs being charged with offences of

criminal negligence in Canada and just over 30

GNM prosecutions since 1830 in England.7

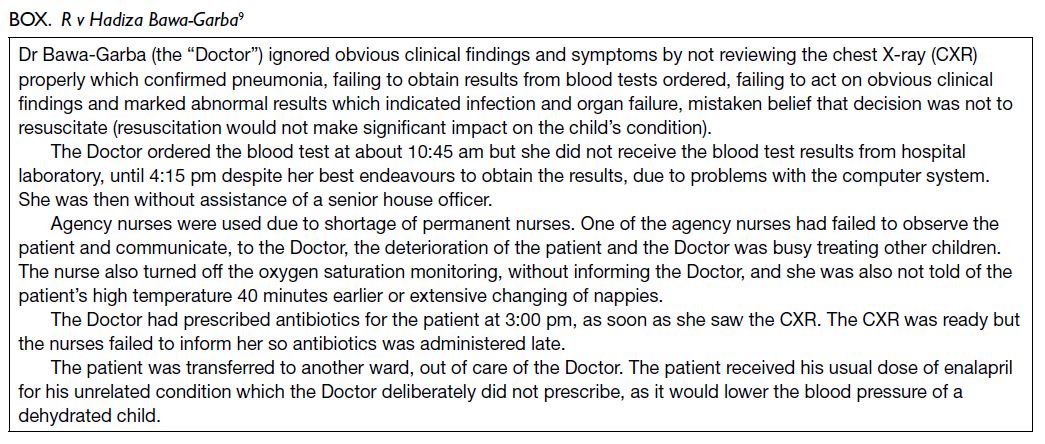

In the Garba case,9 the jury found the defendant

paediatrician’s conduct to be “truly exceptionally

bad” (meaning it was far below the standard of care

expected by a competent paediatrician and that it

amounted to the criminal offence of GNM). The

literature has raised criticisms of the findings for

failing to give due consideration to organisational

factors, such as system failure or lack of permanent

supporting staff.6 10 The Box summarises the

negligence of the defendant doctor and factors

contributing to her negligence.

The investigations and prosecutions regarding

Garba were perceived as arbitrary and inconsistent.11

This resulted in a rapid policy review, as described

in Gross Negligence Manslaughter in Healthcare in

2018.12 The panel was clear that HCPs could not be,

or be seen to be, above the law and should be held to

account where necessary. It was equally evident that

HCPs are working in the complexity of a modern

healthcare system, under a stressful environment

and this should also be taken into consideration when

deciding whether to pursue a GNM investigation.

Doctors who have made an erroneous or suboptimal

decision, without the intent to harm, acted in a

manner that arguably does not rise to the level of

criminal blameworthiness.13

A negligent doctor should not be held

criminally liable for a brief lapse of concentration or

an inadvertent error of judgement and it has been

argued that three factors: (1) awareness; (2) choice

(choose to run the risk); and (3) control (has the opportunity to act differently) should be present

for the establishment of the negligent conduct to be

considered culpable within the criminal context.13 An

error is trying to do the right thing but performing

same wrongly which does not reflect an intentional

deviation from accepted practices.14

Would Garba9 be ruled differently, with

consideration of culpability and violation of the three

factors of awareness, choice and control? Dr Bawa-Garba’s fitness to practise had been found to be

impaired causing her suspension from practising for

1 year by the tribunal. The General Medical Council

appealed, on the ground that the tribunal should

have ordered her to be erased from the register

and substituted the sanction of erasure for that

of suspension.15 The ruling led to a backlash from

doctors who believed that she should not have been

singled out for punishment because of the multiple

system failures which led to the boy’s death. Dr Bawa-Garba finally won an appeal against being struck off,

restoring the 1-year suspension.16 The judgement

states that the task of the tribunal was to decide

what sanction would “most appropriately meet the

overriding objective of protecting the public.”16 Taking

into account the particular circumstances of this

case and the aggravating and mitigating factors, the

Court of Appeal felt that erasure was not necessary

to meet the objectives of: protecting the public;

maintaining public confidence; and promoting and

upholding proper professional standards. The Court

considered that the expert tribunal was entitled to

form the view that a suspension order could meet

these statutory objectives.

Dr Bawa-Garba is now back at work and has

finished her specialist training.17 The main lessons

learned are: to analyse all circumstances; to assess

whether the negligent act is truly exceptionally bad;

and whether there were extenuating circumstances

that need to be taken into account.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: A Lee, T Cheung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: A Lee, T Cheung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This editorial has been presented in the Gross Negligence

Manslaughter Seminar and Panel Discussion: Reflection from

different Jurisdictions adopting Common Law organised by

the Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion of The

Chinese University of Hong Kong and co-organised by the

Centre for Medical Ethics and Law of The University of Hong

Kong, New Medico-Legal Society of Hong Kong, American

College of Legal Medicine, the Australasian College of Legal

Medicine, and the Healthcare Division of Allied World

Assurance Company held in November 2021.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed reflect the views of the authors not the institutions to which they are affiliated.

References

1. Lee A. Clinical liability in Hong Kong: revisiting duty and

standard of care. In: Raposo VL, Beran RG, editors. Medical

Liability in Asia and Australasia. Ius Gentium: Comparative

Perspectives on Law and Justice, vol 94. Singapore: Springer; 2022. Crossref

2. Jones M, Dugdale AM, Simpson M. Clerk & Lindsell on Torts. 23rd Edition, London: Sweet & Maxwell; 2020.

3. Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee. 1 WLR 582; 1957.

4. Hatcher v Black. The Times. 2 July 1954.

5. Meyer JF. Retributive Justice. Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Sep 2014. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/retributive-justice. Accessed 6 Jan 2024.

6. Lee A. Key elements of gross negligence manslaughter in

the clinical setting. Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:99-101. Crossref

7. Farrell AM, Alghrani A, Kazarian M. Gross negligence

manslaughter in healthcare: time for a restorative justice

approach? Med Law Rev 2020;28:526-48. Crossref

8. Anawis M, Beran RG, Cheung T, Ho C, Kim H, Lee A. Gross

Negligence Manslaughter Seminar and Panel Discussion:

Reflection from different Jurisdictions adopting Common

Law. November 2021. Available from: https://www.chep.cuhk.edu.hk/GNM/. Accessed 15 Jan 2024.

9. R v Hadiza Bawa-Garba. EWCA Crim 1841; 2016.

10. Cohen D. Back to blame: the Bawa-Garba case and the

patient safety agenda. BMJ 2017;359:j5534. Crossref

11. Lee DW, Tong KW. What constitutes negligence and gross

negligence manslaughter? In Chiu JS, Lee A, Tong KW,

editors. Healthcare Law and Ethics: Principles and Practices.

Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press; 2023.

12. Department of Health and Social Care of the United

Kingdom. Gross Negligence Manslaughter in Healthcare.

The Report of a Rapid Policy Review. June 2018. Available

from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/717946/Williams_Report.pdf . Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

13. Robson M, Maskill J, Brookbanks W. Doctors are

aggrieved—should they be? Gross negligence manslaughter

and the culpable doctor. J Crim Law 2020;84:312-40. Crossref

14. Merry A, Brookbanks W. Violations. In: Merry and

McCall Smith’s Errors, Medicine and the Law. 2nd Edition.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017: 141-82. Crossref

15. GMC v Dr Bawa-Garba. EWHC 76 (Admin); 2018.

16. Hadiza Bawa-Garba v GMC. EWCA Civ 18979; 2018.

17. Dyer C. Hadiza Bawa-Garba can return to practice under close supervision. BMJ 2019;365:l1702. Crossref