Hong Kong Med J 2024;30:Epub 18 Dec 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Atypical imaging manifestations in non-alcoholic

Wernicke’s encephalopathy: a potentially reversible neurological condition not to be missed

Cherry CY Chan, MB, ChB, FRCR (Radiology)1; Kevin KF Fung, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1,2; Elaine YL Kan, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)2

1 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Radiology, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Cherry CY Chan (chancherrycy@gmail.com)

An 18-year-old female with good past health

was diagnosed with right tibial osteosarcoma in

February 2019. She underwent wide excision of

the right proximal tibia and distal femur with total

knee replacement. Postoperatively, her adjuvant

chemotherapy was complicated by multiple episodes

of opportunistic infection, acute renal impairment

due to drug toxicity and electrolyte disturbance. She

was hospitalised for >6 months with suboptimal oral

intake.

Over the course of a week, the patient had

two episodes of seizure. Her general consciousness

deteriorated acutely to a Glasgow Coma Scale

score of 8/15 (E4V1M3). Physical examination

revealed decorticate posture, generalised flaccidity

and areflexia. Serum sodium level and urea were

markedly elevated (154 mmol/L and 17.0 mmol/L,

respectively), in keeping with hypernatraemic

dehydration. Electroencephalogram showed diffuse

slow-wave encephalopathy. Her Glasgow Coma

Scale score did not improve following correction of

hypernatraemia.

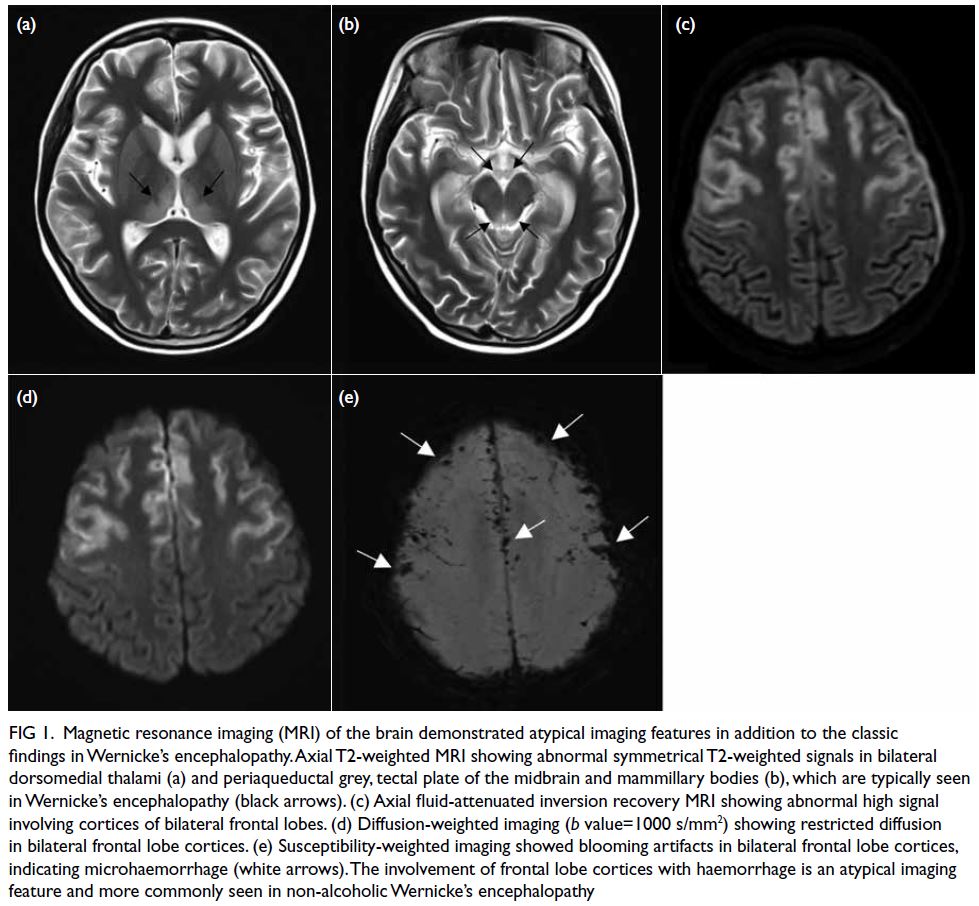

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain

revealed an abnormal high T2-weighted signal

and restricted diffusion in bilateral frontal lobe

cortices, dorsomedial thalami, periaqueductal grey,

tectal plate of the midbrain and mammillary bodies

(Fig 1a-d). Based on these findings, the patient

was diagnosed with Wernicke’s encephalopathy

and high-dose intravenous thiamine (vitamin B1)

was initiated. Although her level of consciousness

improved rapidly, there was poor recovery of limb

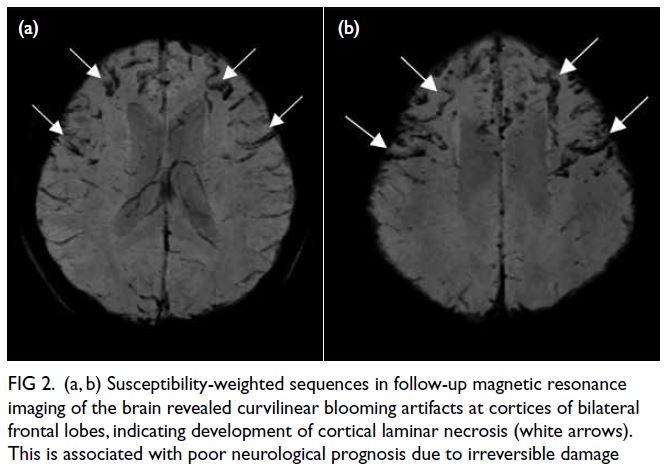

power. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging of

the brain demonstrated cortical laminar necrosis

and haemorrhage at bilateral frontal cortices (Figs 1e and 2). After 2 years of intensive rehabilitation, she regained most of her upper limb power, but lower

limb power remained impaired.

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated atypical imaging features in addition to the classic findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Axial T2-weighted MRI showing abnormal symmetrical T2-weighted signals in bilateral dorsomedial thalami (a) and periaqueductal grey, tectal plate of the midbrain and mammillary bodies (b), which are typically seen in Wernicke’s encephalopathy (black arrows). (c) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI showing abnormal high signal involving cortices of bilateral frontal lobes. (d) Diffusion-weighted imaging (b value=1000 s/mm2) showing restricted diffusion in bilateral frontal lobe cortices. (e) Susceptibility-weighted imaging showed blooming artifacts in bilateral frontal lobe cortices, indicating microhaemorrhage (white arrows). The involvement of frontal lobe cortices with haemorrhage is an atypical imaging feature and more commonly seen in non-alcoholic Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Figure 2. (a, b) Susceptibility-weighted sequences in follow-up magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed curvilinear blooming artifacts at cortices of bilateral frontal lobes, indicating development of cortical laminar necrosis (white arrows). This is associated with poor neurological prognosis due to irreversible damage

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is an acute

neurological syndrome caused by depletion of

intracellular thiamine in neurons that is essential for

production of neurotransmitters. The bodily reserve

of thiamine in a healthy individual is exhausted within

4 to 6 weeks in the absence of dietary thiamine.1

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is most commonly

associated with chronic alcoholism but can result

from any condition that causes malnutrition or

malabsorption.1 The classic clinical triad consists of confusion, ataxia and ophthalmoplegia, although

only a small proportion of patients exhibits all three.2

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy carries

significant neurological morbidity and death. The

condition is potentially reversible if recognised and

treated early with intravenous thiamine replacement.

Classic imaging features of alcohol-associated

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include abnormal signal

involving deep periventricular and periaqueductal

grey matter in basal ganglia and brainstem,

most notably in the mamillary bodies.3 Atypical

findings are more frequently seen in non-alcoholic

Wernicke’s encephalopathy. These include abnormal

signal in other locations such as the cerebral cortex,

splenium, caudate nuclei, red nuclei, cranial nerve

nuclei, cerebellum and vermis.4 Further progression

to cortical laminar necrosis and haemorrhage,

as seen in our case, is rare and associated with a

poor prognosis due to irreversible neurological

damage.5

In patients with a poor nutritional state

who present with reduced consciousness, a high

index of clinical suspicion and prompt imaging are

important to establish the diagnosis of Wernicke’s

encephalopathy. Atypical imaging manifestations

are more commonly seen in non-alcoholic Wernicke’s

encephalopathy. Timely diagnosis is crucial since

the neurological impairment is potentially reversible

with intravenous thiamine replacement therapy.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CCY Chan, KKF Fung.

Acquisition of data: CCY Chan, KKF Fung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: CCY Chan, KKF Fung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: CCY Chan, KKF Fung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: CCY Chan, KKF Fung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for

all treatments and procedures, and consent for publication.

References

1. Chandrakumar A, Bhardwaj A, ’t Jong GW. Review of

thiamine deficiency disorders: Wernicke encephalopathy

and Korsakoff psychosis. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2018;30:153-62. Crossref

2. Harpe CG, Giles M, Finlay-Jones R. Clinical signs in the

Wernicke–Korsakoff complex: a retrospective analysis

of 131 cases diagnosed at necropsy. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry 1986;49:341-5. Crossref

3. Zuccoli. G, Pipitone N. Neuroimaging findings in acute

Wernicke’s encephalopathy: review of the literature. AJR

Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:501-8. Crossref

4. Bae SJ, Lee HK, Lee JH, Choi CG, Suh DC. Wernicke’s

encephalopathy: atypical manifestation at MR imaging.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:1480-2.

5. Pereira DB, Pereira ML, Gasparetto EL. Nonalcoholic

Wernicke encephalopathy with extensive cortical

involvement: cortical laminar necrosis and hemorrhage

demonstrated with susceptibility-weighted MR phase

images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:E37-8. Crossref