Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:67–9 | Number 1, February 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134028

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Transnasal penetrating intracranial injury with a chopstick

SK Chan, MB, BS; KY Pang, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery); CK Wong, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)

Department of Neurosurgery, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital,

Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SK Chan (skc2009@hotmail.com)

Abstract

We report the first case of a transnasal penetrating

intracranial injury in Hong Kong by a chopstick. A

49-year-old man attempted suicide by inserting a

wooden chopstick into his left nose and then pulled

it out. The chopstick caused a transnasal penetrating

brain injury, confirmed by contrast magnetic

resonance imaging of the brain. He was managed

conservatively. Later he developed meningitis without

a brain abscess and was prescribed antibiotics for 6

weeks. He enjoyed a good neurological recovery.

This case illustrates that clinician should have a

high index of suspicion for penetrating intracranial

injury due to a nasally inserted foreign body, even

though it had already been removed. In such cases moreover, brain magnetic

resonance imaging is the imaging modality of choice,

as it can delineate the path of penetration far better

than plain computed tomography.

Case report

A 49-year-old Chinese man, who was a psychiatric

in-patient, self-inserted a wooden chopstick into his left nose and then pulled it out in November 2012. He

was subsequently assessed by an ear, nose and throat

surgeon. No nasal foreign body was seen and there

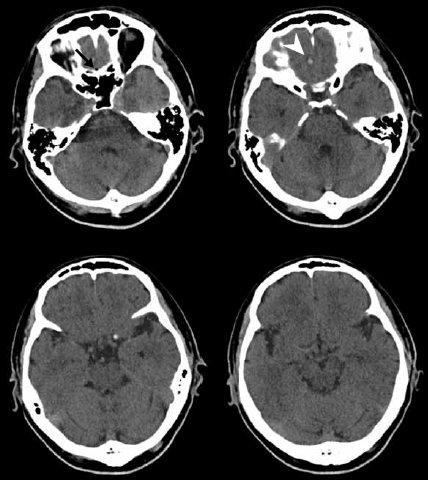

was no epistaxis. Brain computed tomography (CT)

6 hours after the injury showed a trace amount of

haemorrhage over the right gyrus rectus and a small

amount of pneumocephalus over the right anterior

fossa (Fig 1), and hence the neurosurgical unit was

consulted. Six hours after the incident his vital signs

were stable and he was afebrile; his Glasgow Coma

Scale score was E4M6V4. His speech appeared

confused, as if in a premorbid state. There was no

neurological deficit, and no cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

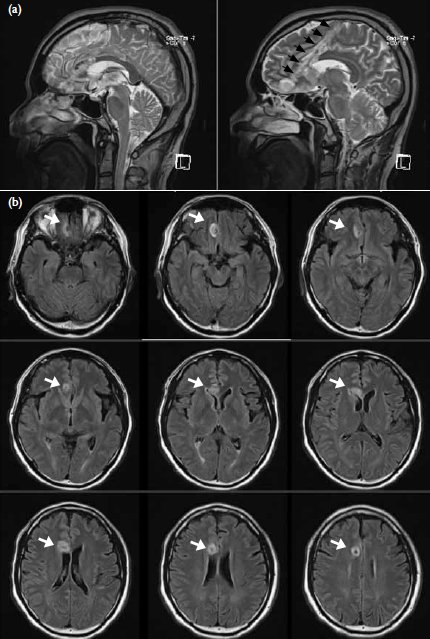

rhinorrhoea upon stress testing. Contrast magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed

on the next day, which showed a long haemorrhagic

tract extending from right paramidline anterior skull

base, coursing postero-superiorly across medial

right frontal lobe, closely adjacent to the right

frontal horn, and ending at the vertex region (Fig 2), and a trace of intraventricular haemorrhage. On

the same day he developed fever. Lumbar puncture

yielded turbid CSF, with the presence of Gram-positive

cocci, as well as low CSF glucose and high CSF

protein concentrations. Conservative management

was adopted. On an empirical basis, intravenous

ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole were

prescribed. Prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy

(phenytoin) was also given. The CSF culture grew

Staphylococcus aureus and Citrobacter koseri. The

antibiotic regimen was switched to intravenous

ceftriaxone and oral metronidazole. The patient’s

recovery was excellent, as reflected by normalisation

of body temperature and inflammatory markers. On day 14, contrast CT brain showed no abscess. He

was well after 6 weeks of antibiotic treatment.

Figure 1. Plain computed tomographic scan of brain (axial cut) showing pneumocephalus (black arrow) and haemorrhage over right gyrus rectus (white arrowhead)

Figure 2. (a) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of brain (sagittal cut) showing transected track (black arrows). (b) T2-weighted MRI scan of brain in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence (axial cut) showing transected track (white arrows)

Discussion

A literature search of the MEDLINE database

(using the key words "transnasal" and "penetrating

intracranial injury", or the other similar keywords)

was conducted. Approximately 10 case reports were

identified, indicating this was an exceedingly rare

condition. We report the first case of a transnasal

penetrating intracranial injury in Hong Kong by

means of a chopstick. The majority of patients with

this mechanism of injury were due to accidental falls

on objects that enter the nostril,1 while few were

due to attempted suicide. This mode of penetrating

intracranial injury can result in severe complications,

including CSF rhinorrhoea and infection (meningitis

and/or brain abscess).2 The source of the bacteria

could have been from the chopstick or the normal

flora in the nasal cavity/paranasal sinuses. Such injury

can also result in blindness or ophthalmoplegia,3

if the orbital cavity is involved. The most dreadful

complication is severe haemorrhage due to internal

carotid artery injury, which may lead to immediate

death.1 Although foreign body in the nose is a

common presentation, clinicians should always have

a high index of suspicion for possible transnasal

penetrating intracranial injury. Such vigilance

is especially necessary in patients who cannot

volunteer a clear history or complaint (eg children or

psychiatric patients), are febrile, have a neurological

deficit, or have continuous epistaxis.

All patients with penetrating brain

injury should have adequate neuroradiological

examinations.4 Plain CT brain is the initial

investigation of choice to explore for the presence

of any retained radio-opaque material. It can also

reveal presence of an intracranial haematoma or

air, or focal heterogeneous hypodensity suggestive

of brain abscess. Contrast MRI of the brain with

cerebral angiography is the best method of evaluating

penetrating brain injuries. Besides the previously

mentioned abnormal findings, it can also delineate

the track transected by the foreign body, even after it

has been removed, as in this case. Had contrast MRI

brain not been arranged for this patient, penetrating

brain injury would probably have been missed,

given the seemingly unalarming brain CT (Fig 1).

Brain abscess or vascular damage, if any, can also be

appreciated using brain MRI.

Management depends on patient’s condition

and whether a complication has developed.

Neuroendoscopy is a useful operative tool, which

can be employed to remove foreign body or repair

the dural defect causing CSF rhinorrhoea,5 whenever

conservative management fails. Craniotomy may be

warranted if there is a sizable abscess or cerebral

haemorrhage. Since the patient did not have these complications, he was managed conservatively.

Initially, he received empirical intravenous broad-spectrum

antibiotics, as for the treatment of a

bacterial cerebral abscess. The CSF should be

obtained and cultured if the patient has a fever.

Targeted antibiotics can then be used depending

on the sensitivity results. The patient was also

instructed to lie flat to prevent CSF leakage. Short-term

prophylactic anticonvulsant should also be

prescribed.

Conclusion

Herein we report the first patient with a transnasal

penetrating intracranial injury in Hong Kong

resulting from a chopstick. Such injuries confer

significant mortality or morbidity, for which

clinicians should always have a high index of

suspicion. The neuroimaging of choice involves

contrast MRI brain with cerebral angiography. Operative management can be considered for those

patients who have a foreign body in situ, a sizable

abscess or haemorrhage, or CSF rhinorrhoea.

References

1. Ihama Y, Nagai T, Ninomiya K, Fukasawa M, Fuke C, Miyazaki T. A transnasal intracranial stab wound by a plastic-covered umbrella tip. Forensic Sci Int 2012;214:e9-e11. Crossref

2. Hiraishi T, Tomikawa M, Kobayashi T, Kawaquchi T. Delayed brain abscess after penetrating transorbital injury [in Japanese]. No Shinkei Geka 2007;35:481-6.

3. Liu SY, Cheng WY, Lee HT, Shen CC. Endonasal transsphenoidal endoscopy-assisted removal of a shotgun pellet in the sphenoid sinus: a case report. Surg Neurol 2008;70 Suppl 1:S1:56-9.

4. Sharif S, Roberts G, Phillips J. Transnasal penetrating brain injury with a ball-pen. Br J Neurosurg 2000;14:159-60.

Crossref

5. Lee DH, Seo BR, Lim SC. Endoscopic treatment of

transnasal intracranial penetrating foreign body. J

Craniofac Surg 2011;22:1800-1. Crossref