Hong Kong Med J 2024 Aug;30(4):332–6 | Epub 5 Aug 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

The Hong Kong Renal Registry: a recent update

John YH Chan, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; YL Cheng, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)2; SK Yuen, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)3; PN Wong, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)4; HM Cheng, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)5; KL Mo, MB, BS, FHAKM (Medicine)6; CY Yung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)7; KM Chow, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)8; Samuel KS Fung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)9; WL Chak, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Maggie KM Ma, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)10; TL Ho, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)11; Achilles Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)12; Sunny Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)13; SF Cheung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)14; Alison LT Ma, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)15 CC Szeto, MD, FHKAM (Medicine)16; Sydney CW Tang, MD, FHKAM (Medicine)17; SL Lui, MD, FHKAM (Medicine)18

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Medicine, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Department of Medicine, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Department of Medicine, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Pok Oi Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

10 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

11 Department of Medicine, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

12 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

13 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

14 Department of Medicine, Yan Chai Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

15 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

16 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

17 Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

18 Department of Medicine, Tung Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr John YH Chan (chanyhj@ha.org.hk)

Introduction

The Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA) provides

>90% of renal replacement services for kidney failure

with replacement therapy (KFRT) [previously termed

end-stage renal failure] patients in Hong Kong.1 The

HA Renal Registry, established in April 1995,1 is

an online computerised registry system developed

by the HA Central Renal Committee to capture

data regarding all KFRT patients with treatment

provided by the HA. Reports of the Renal Registry

were published in 1999,2 2013,3 and 2015.1 This

report constitutes an update on the epidemiology of

chronic kidney disease in Hong Kong based on data

from the Renal Registry up to 31 December 2022.

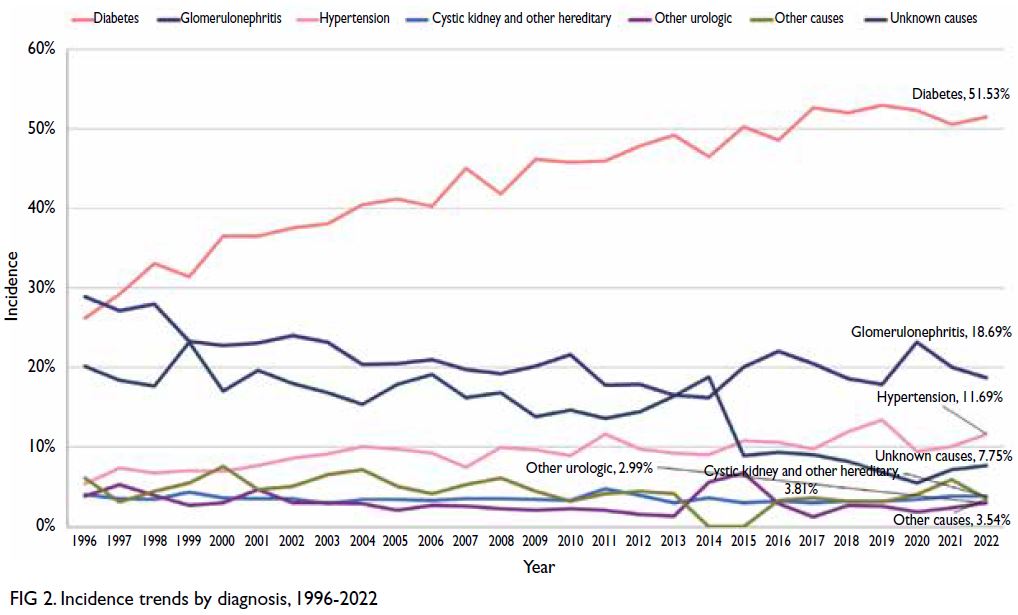

Incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy

During 2022, 1471 new patients entered the KFRT

programme at an incidence of 197.5 per million

population (pmp), an 0.34% increase compared with

2021. Since the establishment of the Renal Registry

in 1995, the number of new patients increased by

139%, from 615 per year (95.1 pmp) in 1996 to a

peak of 1471 per year (197.5 pmp) in 2022 (Fig 1). As HA has had peritoneal dialysis (PD)–first policy,4

82.3% (n=1211) of new patients received PD, 17.0%

(n=250) received haemodialysis (HD), and 0.7%

(n=10) underwent kidney transplantation in 2022.

The male-to-female ratio among new patients was

1.8:1. For new patients in the HD and PD groups, the

greatest increase was observed among those aged 45

to 64 years, followed by those aged 65 to 74 years.

The median age of new KFRT patients in 2022 was

63.4 years, a substantial increase compared with the

median age of 51.4 years in 2013.1 Among new PD patients in 2022, 15.4% were aged >70 years.

Fig 1. Incidence rates of different modalities of kidney failure with replacement therapy, 1996-2022

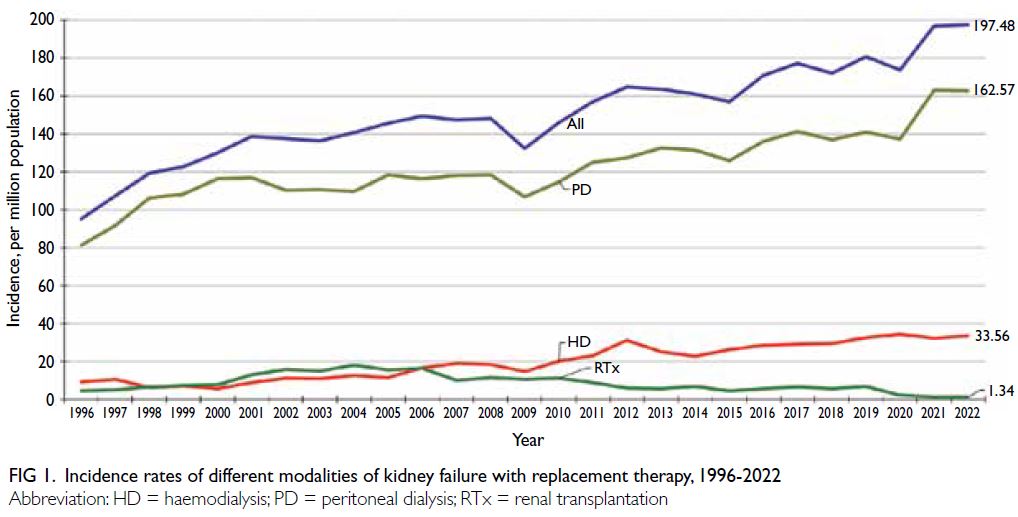

Since 1997, diabetes mellitus (DM) has been the

most common aetiology leading to kidney failure in

Hong Kong (Fig 2). In 2022, the percentage of KFRT

cases attributable to DM was 51.5% and among

the highest percentages worldwide,5 followed by

glomerulonephritis (18.7%) and hypertension (11.7%).

Over the 26 years from 1996 to 2022, the percentage of

KFRT cases attributable to DM increased from 26.2%

in 1996 to >50% beginning in 2017. The percentage

of KFRT cases attributable to glomerulonephritis

steadily decreased from 28.9% in 1996 to 18.7%

in 2022. The percentage of other causes remained

relatively stable between 2012 and 2022 (Fig 2).

Point prevalence of kidney failure

with replacement therapy

As of 31 December 2022, there were 11 115 patients

registered in the Renal Registry, representing a

prevalence of 1492 pmp. Among these patients,

5148 (46.3%) were receiving PD, 2452 (22.1%) were

receiving HD, and 3515 (31.6%) had a functioning

graft kidney. From 1996 to 2022, the number of KFRT patients in Hong Kong increased by 236%,

despite 49 fewer patients in 2022 causing a decrease

in the prevalence by 0.4%. This was likely due to

the substantial decrease (4.3%) in the prevalence

of patients with a functioning graft kidney, from

493.4 pmp in 2021 to 471.1 pmp in 2022 (online supplementary Fig 1). Between 1996 and 2022, the median patient age increased from 49.1 years to 61.0 years; in 2022, 12.4% of patients were aged >75

years and the male-to-female ratio among all KFRT

patients was 1.38:1.

Modes of renal replacement therapy

Peritoneal dialysis

Hong Kong has had a PD-first policy since 1985.4 All

new patients requiring dialysis therapy receive PD

unless they have medical contraindications to such

treatment. As of 31 December 2022, there were 5148

patients receiving PD in Hong Kong, representing a

prevalence of 691 pmp. These patients constituted

48.2% of all patients receiving renal replacement

therapy and 73.2% of all patients receiving dialysis

therapy. The number of patients receiving PD

was 1.2% higher in 2022 than in 2021. Since

establishment of the Renal Registry, the number of

patients receiving PD has increased by 176%, from

1865 in 1995 to 5148 in December 2022. Beginning

in 2020, the number of patients receiving automated

PD therapy also substantially increased. In 2022,

1330 patients received automated PD, constituting

25.8% of all PD patients. The overall peritonitis rate

among patients receiving continuous ambulatory

PD has greatly improved, from 0.55 episode per

patient-year in 1999 to 0.27 episode per patient-year

in 2022. Moreover, patients receiving automated PD

had a peritonitis rate of 0.23 episode per patient-year,

which was better than the rate among patients

receiving continuous ambulatory PD.

Haemodialysis

As of 31 December 2022, there were 2452 patients

receiving HD in the Renal Registry, representing a

prevalence of 329 pmp; this rate constituted a 2.0%

increase compared with 2021. Although PD remains

the main treatment for KFRT patients in Hong

Kong, there has been an increase in the provision of

HD services by the HA for patients with PD failure

or not suitable to receive PD. As of 31 December

2022, 1866 patients received HD services provided

by HA, including 1294 who were receiving in-centre

HD in HA facilities; this represented a 249% increase

compared with 371 patients in 1996. The proportion

of HD among all KFRT treatment modalities also

increased from 11% in 1996 to 17.6% in 2022,

resulting in the HD-to-PD ratio of 0.37:1. Since

the introduction of the nocturnal home dialysis

programme in 2006 and New Generation Home

HD in 2020, HA home HD services have expanded.

In 2022, 220 patients participated in home HD

programmes, representing 12% of all HD services

provided by the HA.

Kidney transplantation

In 2022, the number of patients with a functioning graft kidney continued to decline for the fourth

consecutive year since 2019. As of 31 December 2022,

there were 3515 patients with a functioning graft

kidney (3058 deceased donor transplants and 457

living donor transplants), representing a prevalence

of 472 pmp; this rate constituted a 4.3% decrease

compared with 2021. Among the 3515 transplant

recipients, 1198 patients underwent transplantation

in Hong Kong; these patients comprised 34.1% of the

overall kidney transplant population. The number of

patients with a functioning graft kidney increased

during 1995 (956 patients) and 2019 (3779 patients);

since then, the number has continuously decreased.

The overall increase during the analysis period was

due to the 364% increase in the number of deceased

donor transplant recipients (from 659 in 1996 to

3058 in 2022), whereas the increase in the number

of living donor transplant recipients was relatively

modest (ranging from 297 in 1996 to 457 in 2022).

In 2022, there were 45 deceased donor

(6.2 pmp) and 11 living donor (1.5 pmp) kidney

transplant surgeries performed in Hong Kong,

among the lowest rates worldwide.5 In terms of

transplant outcomes, the death-censored graft

survival rates for living donor kidney transplant

surgeries performed in Hong Kong during 2010 and

2019 were 0.97 at 1 year and 0.94 at 5 years, while

that for deceased donor kidney transplant surgeries

were 0.97 at 1 year and 0.89 at 5 years.

Mortality

The crude mortality rate among KFRT patients in Hong Kong remained stable at approximately 100

deaths per 1000 patient-years from 2012 to 2021

(online supplementary Fig 2). In 2022, possibly due to

the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, there was an

increase in the crude annual mortality rate to 147.9

deaths per 1000 patient-years. The annual mortality

rate increased with increasing age for all KFRT

treatment modalities. The highest rate was observed

among patients aged ≥75 years: >300 deaths per 1000

patient-years for both PD and HD patients. Overall,

transplant recipients had better survival than PD or

HD patients. Even among patients aged ≥75 years,

those receiving PD had a relative mortality risk 2.7-fold higher than the risk for transplant recipients.

Infection remained the most common cause

of death among KFRT patients (46.0% in 2022),

followed by cardiovascular disease (26.2%) and

cerebrovascular disease (4.1%) [online supplementary Fig 3]. Malignancy caused 12.4% of all deaths in

transplant recipients. Because of improved hepatitis

treatment for transplant recipients, liver failure has

caused <1% of deaths in recent years.

Discussion

The incidence and prevalence of KFRT have substantially increased since the establishment of the Renal Registry. Considering these trends,

the kidney disease epidemic constitutes a serious

burden on the healthcare system in Hong Kong.

Diabetes mellitus continues to be a leading cause

of KFRT in Hong Kong; this rate is among the top

quartile worldwide.5 There may be multiple reasons,

including the increasing prevalence of young-onset

DM6 7 and improved survival of DM patients with

cardiovascular disease.7 In 2020, the Asian Pacific

Society of Nephrology published a clinical practice

guideline that focused on the management of

diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in the Asia-Pacific

region.8 The Kidney Disease: Improving Global

Outcomes group also updated its Guideline for

Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease in

2022.9 Based on the collaborative efforts to provide

better care for patients with DKD, we hope to see

fewer new cases of KFRT attributable to DKD and a

decrease in the growth of KFRT incidence in Hong

Kong in the coming years.

By the end of 2022, >70% of prevalent

KFRT patients received PD. When considered in

combination with home HD, around 75% of the

dialysis population in Hong Kong is receiving

home-based dialysis therapy; this is the highest rate

worldwide.5 The benefits of this therapy were evident

during the coronavirus disease 2019 era.10 However,

home HD patients constituted approximately 3%

of all dialysis patients. It may be time to explore

the feasibility of modifying the PD-first policy to a

home-dialysis–first policy with further expansion

of home HD services for suitable patients, allowing

patients to maintain greater autonomy and freedom

when selecting their dialysis modality; this approach

could also serve as a transitional treatment method

for patients with PD failure before they begin in-centre

HD therapy.

Kidney transplant recipients continue to

display the lowest annual mortality rates. However,

the number of transplant surgeries in Hong Kong

remains low. In 2022, the transplant rate (including

both living and deceased donor surgeries) was 7.2 pmp, which ranked in the lowest quartile worldwide.5

Furthermore, only around 34% of patients with

a functioning graft kidney underwent surgery in

Hong Kong; many of the remaining patients chose

to undergo surgery elsewhere. Currently, there

are >2000 patients on the waiting list for a kidney

transplant in Hong Kong. It appears that there

are further opportunities for improvement in

transplantation services, particularly concerning the

promotion of living organ donation activities, the

willingness of relatives of potential brain-dead donors

to permit organ donation, and further expansion of

the donor pool. Considering the implementation of

the paired kidney donation programme and ABO-incompatible

transplantation programme, we look

forward to seeing increases in organ transplantation activities within Hong Kong that will benefit KFRT

patients in the future.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JYH Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KM Chow, CC Szeto, SCW Tang, SL Lui.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JYH Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KM Chow, CC Szeto, SCW Tang, SL Lui.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all medical and nursing staff members

of Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Caritas Medical

Centre, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Kwong Wah Hospital,

North District Hospital, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern

Hospital, Pok Oi Hospital, Prince of Wales Hospital, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Queen Mary

Hospital, Tin Shui Wai Hospital, Tseung Kwan O Hospital,

Tuen Mun Hospital, Tung Wah Hospital, United Christian

Hospital, and Yan Chai Hospital for contributions to the entry

of renal registry data. The authors also appreciate the support

of all transplant coordinators and staff members of the

Division of Transplantation and Immunogenetics of Queen

Mary Hospital, and thank members of the Renal Registry

Steering Group of the Central Renal Committee, Hospital

Authority and members of the Renal Registry Implementation

Team for their support and implementation of the Hong Kong

Renal Registry.

Funding/support

This commentary received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Leung CB, Cheung WL, Li PK. Renal registry of Hong Kong—the first 20 years. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2015;5:33-8. Crossref

2. Lui SF, Ho YW, Chau KF, Leung CB, Choy BY. Hong Kong Renal Registry 1995-1999. Hong Kong J Nephrol 1999;1:53-60. Crossref

3. Ho YW, Chau KF, Choy BY, et al. Hong Kong Renal Registry

Report 2012. Hong Kong J Nephrol 2013;15:28-43. Crossref

4. Li PK, Lu W, Mak SK, et al. Peritoneal dialysis first policy

in Hong Kong for 35 years: global impact. Nephrology

(Carlton) 2022;27:787-94. Crossref

5. United States Renal Data System. 2023 USRDS Annual

Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United

States. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health,

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney

Diseases; 2023.

6. Luk AO, Ke C, Lau ES, et al. Secular trends in incidence of

type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Hong Kong: a retrospective

cohort study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003052. Crossref

7. Wu H, Lau ES, Yang A, et al. Trends in kidney failure

and kidney replacement therapy in people with diabetes

in Hong Kong, 2002-2015: a retrospective cohort study.

Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021;11:100165. Crossref

8. Liew A, Bavanandan S, Prasad N, et al. Asian Pacific Society

of Nephrology Clinical Practice Guideline on Diabetic

Kidney Disease—an executive summary. Nephrology

(Carlton) 2020;25:809-17. Crossref

9. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)

Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice

Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney

Disease. Kidney Int 2022;102(5S):S1-127. Crossref

10. Wilkie M. Home dialysis—an international perspective.

NDT Plus 2011;4(Suppl 3):iii4-6. Crossref