Hong Kong Med J 2024 Jun;30(3):227–32 | Epub 10 May 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Transurethral water vapour thermal therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia under local anaesthesia alone: initial experience in Chinese patients

KL Lo, MB, ChB, FRCSEd; Alex Mok, MB, ChB; Ivan CH Ko, MB, ChB; Steffi KK Yuen, MB, BS, FRCSEd; Peter KF Chiu, MB, BS, FRCSEd; CF Ng, MD, FRCSEd

SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof CF Ng (ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluated the perioperative

and early postoperative outcomes of transurethral

water vapour thermal therapy (WVTT) under local

anaesthesia alone for benign prostatic enlargement

in Chinese patients.

Methods: This retrospective review of transurethral

WVTT for benign prostatic enlargement focused

on 50 Chinese patients who exhibited clinical

indications (acute retention of urine or symptomatic

lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic

enlargement) for surgical treatment between June

2020 and December 2021 in Hong Kong. Exclusion

criteria included active urinary tract problems and

urological malignancies. Follow-up was conducted

at 3 months postoperatively.

Results: The median patient age was 71.5 years. The

mean preoperative prostatic volume was 56.7 mL.

The mean operation time was 25.1 minutes. All

procedures were performed under local anaesthesia

alone. The mean pain scores for transrectal

ultrasound probe insertion, transperineal local

anaesthesia injection, and transurethral WVTT were

2, 5, and 4, respectively. Forty-nine patients (98%)

were discharged on the same day with a urethral

catheter. Forty-eight patients (96%) successfully

completed a trial without catheter within 3 weeks postoperatively. Five patients (10%) had unplanned

hospital admission within 30 days postoperatively

due to surgical complications (Clavien–Dindo grade 1).

Conclusion: Transurethral WVTT, an advanced

surgical treatment for benign prostatic enlargement,

is a safe procedure that relieves lower urinary tract

symptoms with minimal hospital stay. It can be

performed in an office-based setting under local

anaesthesia, maximising utilisation of the surgical

theatre.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first study concerning the efficacy and safety profile of water vapour thermal therapy (WVTT) in Asian patients. It can relieve lower urinary tract symptoms with minimal hospital stay.

- This is the first study of WVTT in an office-based setting under local anaesthesia, maximising utilisation of the surgical theatre.

- Water vapour thermal therapy is an effective and safe alternative for patients who have high surgical risk of benign prostatic enlargement under general or spinal anaesthesia.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is characterised

by a non-malignant growth in the prostate gland

that can cause a wide range of lower urinary tract

symptoms (LUTS). These symptoms can greatly

reduce a patient’s quality of life (QoL) and may

eventually lead to acute retention of urine (AROU).

Current standard treatments for BPH include conservative, pharmacological, and surgical approaches. For patients who fail to successfully

complete a trial without catheter (TWOC) after

AROU secondary to BPH, surgical intervention

remains the main therapeutic approach. Surgical

treatment options for BPH have evolved from

electrosurgical resection to enucleation, ablation of

the prostate, and other techniques.1 Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), first performed

over 90 years ago, continues to be regarded as the

gold standard for the treatment of BPH with prostatic

volumes of 30 to 80 mL.2 Although TURP results in

statistically significant improvements in symptom

scores and maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), it

has some limitations. Perioperative morbidities and

complications of TURP include infection, bleeding,

urinary retention, incontinence, urethral stricture,

erectile dysfunction, and ejaculatory dysfunction.

Additionally, TURP requires general or spinal

anaesthesia and postoperative hospitalisation.

Through technological advancements, several

minimally invasive procedures (eg, UroLift and

prostatic artery embolisation) have been developed

for specific groups of patients with BPH to minimise

the aforementioned limitations.3 4 5 Among these new-generation

BPH surgical approaches, transurethral

water vapour thermal therapy (WVTT) provides

some of the best surgical outcomes.

Transurethral WVTT uses the thermodynamic

principle of convective energy transfer, whereas

other techniques (eg, transurethral microwave

thermotherapy or transurethral needle ablation of

the prostate) involve conductive heat transfer.6 The

thermal therapy system consists of a generator with

a radiofrequency power supply that creates water

vapour from sterile water, as well as a disposable

transurethral delivery device. The tip of the delivery

device contains an 18-gauge needle with 12 small

emitter holes circumferentially arranged for water vapour dispersion into the targeted prostatic tissue.

The release of thermal energy causes tissue necrosis.

The most important characteristic of this technique

is that, during treatment of the transitional zone,

energy is only deposited within this specific region

of the prostate. Reviews of histological evidence

and magnetic resonance images have revealed that

thermal lesions are limited to the transitional zone

without affecting the peripheral zone, bladder,

rectum, or striated urinary sphincter.7 8 At 6 months

after treatment, the total prostatic volume is reduced

by 28.9% and the resolution of thermal lesions, as

determined by gadolinium-enhanced magnetic

resonance imaging, is almost complete.8

A pilot study showed that transurethral WVTT

can serve as a safe and effective treatment in men

with LUTS due to BPH.8 In the first multicentre,

randomised controlled study, 197 men were enrolled

and randomised in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with the

transurethral WVTT or a sham procedure.9 The

sham procedure consisted of rigid cystoscopy with

sound effects that mimicked the thermal treatment.

The primary efficacy endpoint was met at 3 months:

relief of symptoms, measured as a change in

International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), was

detected in 50% of patients in the thermal treatment

group compared with 20% of patients in the sham

procedure group (P<0.0001). In the thermal

treatment group, the Qmax increased by 63%—from

9.9 mL/s to 16.1 mL/s (P<0.0001)—after 3 months.

This clinical benefit was sustained throughout

the study period, with a 54% improvement at the

12-month follow-up. In the most recent update

regarding 5-year outcomes, the improvement in

voiding (as measured by IPSS and uroflowmetry)

had persisted for 5 years, with a surgical retreatment

rate of 4.4%.10

Thus far, studies of transurethral WVTT for

BPH have mainly focused on Caucasian populations.

To provide information regarding its tolerability

and effectiveness in the Chinese population, this

study investigated the safety profile and efficacy of

transurethral WVTT under local anaesthesia alone

for BPH among Chinese patients in Hong Kong.

Methods

Study protocol

This retrospective study investigated transurethral

WVTT for benign prostatic enlargement. The

inclusion criteria included Chinese ethnicity and

clinical indications for surgical treatment, including

AROU or symptomatic LUTS due to benign prostatic

enlargement. Exclusion criteria included active

urinary tract problems such as infection, bleeding

disorder, bladder pathologies (eg, bladder stones and

neurogenic bladder), and urethral stricture, as well

as urological malignancies including bladder and

prostate cancer.

Intervention

The procedure was performed with perioperative

antibiotic prophylaxis. Patients were placed in the

dorsal lithotomy position. After local anaesthesia,

cystoscopy was performed to assess the anatomy of

the bladder and prostate. A specialised handpiece

with an optical lens was inserted under direct visual

guidance into the prostate channel. Treatment began

with the needle tip visually positioned and inserted

approximately 1 cm distal to the bladder neck. Each

treatment lasted for 9 seconds. After 9 seconds,

an audible signal was produced by the system and

the treatment needle was retracted. The handpiece

was then repositioned 1 cm distal to the previous

treatment site; repositioning was repeated until

reaching a treatment site immediately proximal

to the verumontanum. During each water vapour

injection, the majority of the targeted tissue was

treated. All treatment cycles involving one lateral

lobe were completed as a group to utilise residual

heat from prior treatments involving that lobe.

Subsequently, the contralateral lateral lobe was

treated in a similar manner. An enlarged median

lobe could be treated by positioning the needle at a

45-degree angle towards the targeted lobe using the

same technique. After the procedure, a 14-Fr Foley

catheter was inserted. A 1-week course of antibiotic

treatment was administered after surgery.10 Patients

were discharged with the urethral catheter and

readmitted for a TWOC at approximately 1 to 2

weeks after surgery. Upon satisfactory completion of

the TWOC, patients were scheduled for follow-up at

3 months postoperatively.

Statistical analysis

Preoperative parameters and perioperative outcomes

were collected and tabulated using SPSS software

(Windows version 28.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States). Descriptive statistics were used to

summarise the demographic data and perioperative

patient characteristics. Paired sample t tests were

used to compare continuous variables with normal

distributions; the Mann-Whitney U test was used

to compare continuous variables with skewed

distributions, and the Chi squared test was used to

compare categorical variables. Two-sided P values of

<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

Between June 2020 and December 2021, 50 eligible

patients were included in this study. The median

age was 71.5 years (interquartile range [IQR]=64-75.25). In terms of indications, 27 patients (54%) had

symptomatic BPH, 13 patients (26%) had AROU with

a urethral catheter, and 10 patients (20%) had AROU

without a urethral catheter. Of the 50 patients, 39 (78%) were categorised as American Society of

Anesthesiologists class 2, whereas the remaining 11

were categorised as class 3. Most patients (68%) did

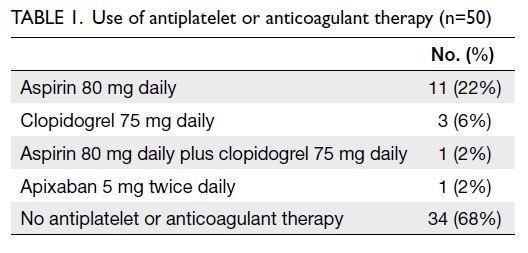

not use any antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. The

numbers of patients using aspirin, clopidogrel, dual

antiplatelet therapy, and apixaban were 11 (22%),

three (6%), one (2%), and one (2%), respectively.

All antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents were

temporarily discontinued before the operation

(Table 1).

Operation

The mean preoperative prostatic volume was 56.7

mL (standard deviation [SD]=24.6; range, 29.2-119.0). The mean operation time was 25.1 minutes

(SD=8.4). All procedures were conducted under local

anaesthesia alone. Lignocaine 1% with adrenaline

was injected into the periprostatic space using a

transperineal approach. The mean pain scores for

transrectal ultrasound probe insertion, transperineal

local anaesthesia injection, and transurethral WVTT

were 2, 5, and 4, respectively.

Postoperative course

Only one patient (2%) required bladder irrigation for

5 days postoperatively; that patient had been taking

apixaban before surgery. All other patients were

discharged on the same day with a urethral catheter.

A TWOC was planned at around 1 week (for the

AROU without urethral catheter or symptomatic

BPH group) to 2 weeks (for the AROU with urethral

catheter group) after surgery. Forty-eight patients

(96%) in our study successfully completed a TWOC

within 3 weeks postoperatively; the median time was

7 days (IQR=7-14). The median successful TWOC

times were 14 days (IQR=8-21) for the AROU

with urethral catheter group and 7 days (IQR=7-12) for the AROU without urethral catheter or

symptomatic BPH group. Two patients (4%) with

an initially unsuccessful TWOC began temporary

clean intermittent self-catheterisation; they were

subsequently weaned from this management

approach on postoperative days 40 and 45,

respectively.

Five patients (10%) had unplanned hospital

admission within 30 days postoperatively due to

surgical complications (Clavien–Dindo grade 1). The reasons for readmission are listed in Table 2.

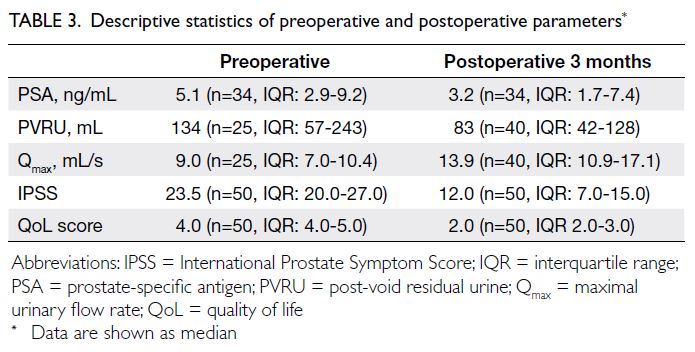

There were significant differences in

preoperative and 3-month postoperative parameters,

including prostate-specific antigen level, post-void

residual urine (PVRU) level, Qmax, IPSS, and QoL

assessment. Table 3 shows the medians and IQRs

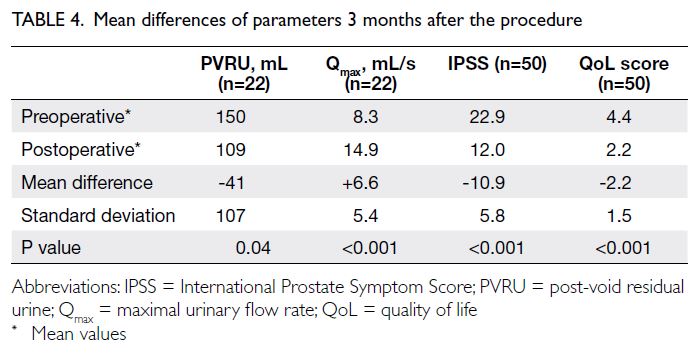

of these data. As indicated in Table 4, the mean

differences in PVRU, Qmax, IPSS, and QoL score were

-41 mL (SD=107), +6.6 mL/s (SD=5.4), -10.9 points

(SD=5.8), and -2.2 points (SD=1.5), respectively.

No patients in this study exhibited de novo

retrograde ejaculation or stress urinary incontinence

at 3 months postoperatively. However, there were

three reported cases (6%) of new-onset erectile

dysfunction postoperatively. All three patients

had temporary erectile dysfunction that resolved within 6 months postoperatively without requiring

medication.

Discussion

Our study is the first to focus on the application of

transurethral WVTT (Rezūm therapy) under local

anaesthesia alone among Chinese men with BPH.

Our results demonstrated clinically significant

outcomes comparable to other treatments for

BPH. Transurethral WVTT provided effective

symptomatic improvement, as illustrated by a

decrease in PVRU of 41 mL, an increase in Qmax of

6.6 mL/s, and a substantial decrease in IPSS of 10.9 at

the 3-month follow-up (Table 4). These results were

also comparable to outcomes in a recent international

study of this therapy.10 The postoperative outcome

was favourable, with a successful TWOC rate of

96% within 3 weeks postoperatively. Moreover,

all patients with urethral catheters before surgery

successfully completed a TWOC after transurethral

WVTT. The median successful TWOC time was

7 days postoperatively. However, compared with

data from other studies (4.1 to 5 days),11 12 our

centre had a longer duration of catheterisation,

which could be explained by our centre’s policy

of scheduling a TWOC on postoperative days 7

and 14 for patients without and with a urethral

catheter before surgery, respectively. Five patients

were readmitted within 30 days after surgery due

to haematuria, post-obstructive diuresis, recurrent

AROU, and urinary tract infection with AROU

(Table 2). All were uneventfully discharged without

further readmission; none of them developed

postoperative urinary incontinence. Three patients

reported de novo erectile dysfunction, higher than

the rate observed in the recent international study.10

However, the rate remained significantly lower

than that associated with TURP.13 Considering the

minimally invasive nature of this procedure, it could

revolutionise future management of BPH.

The current management algorithm for BPH

does not include transurethral WVTT as a first-line

treatment due to the relative lack of evidence

regarding its mid- to long-term efficacy and safety.2

However, it has considerable potential in the

management of BPH because of unique advantages compared with TURP. Transurethral WVTT

can be an office-based procedure with a short

learning curve. If a surgeon completes 10 cases of

transurethral WVTT under supervision, he/she will

become independent from a surgical trainer. Because

BPH is a particularly common urological disease and

often requires surgical management,14 the minimally

invasive nature of transurethral WVTT can help

reduce the number of patients waiting for operations

in overcrowded hospital facilities. The results of our

study provide initial evidence that transurethral

WVTT is well-tolerated among patients under

local anaesthesia alone. We did not administer any

sedation to the patients because they might move

during the operation, resulting in a high risk of

water vapour leakage. Such leakage would lead to

inadequate treatment.

In Hong Kong, total health costs represent

about 19% of the total government budget,15

and public in-patient health costs in 2021/2022

constituted 32% of total health costs.16 Operation

time is one of the most important factors affecting

in-patient costs. According to a meta-analysis by

Mamoulakis et al17 in 2009, the mean operation time

for TURP ranged from 39 to 79 minutes. In the present

study, the mean operation time was 25.1 minutes.

Thus far, no studies have directly assessed the cost-effectiveness

of transurethral WVTT in the Chinese

population. In the United States, a cost-effectiveness

analysis of six therapies for BPH, published in 2018,18

showed that transurethral WVTT was more cost-effective

than other minimally invasive therapies,

such as combination medical treatment and UroLift.

Moreover, McVary et al10 reported that the 5-year

retreatment rate after transurethral WVTT was

4.4%, which was significantly lower than that after

UroLift therapy (13.6%) reported by Roehrborn et al.5

Notably, transurethral WVTT leads to lower

incidences of bleeding, urgency, urge incontinence,

and ejaculatory dysfunction compared with TURP.19

The more favourable side-effect profile has resulted

in considerable interest concerning its potential to

replace TURP as the first-line surgical treatment in

the future. No head-to-head trials have compared

other surgical modalities with transurethral WVTT.

Indirect comparison through a meta-analysis

revealed that TURP outperformed transurethral

WVTT by providing greater relief of LUTS,19 although

it carried a greater cost and higher complication

rate.18 Although pharmacological treatment is

currently the first-line treatment for moderate to

severe LUTS, it is associated with complications such

as dizziness, postural hypotension, reduced libido,

and erectile dysfunction. Gupta et al20 compared

standard medical therapy with transurethral WVTT

using cohort data from the MTOPS trial (Medical

Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms); they showed that

transurethral WVTT had superior outcomes in terms of QoL, IPSS, and prostatic volume reduction.

Considering these advantages, transurethral WVTT

can be regarded as a first-line treatment option for

patients with symptomatic LUTS who prefer a short

operation, rather than lifelong pharmacological

treatment.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this study. First, a

substantial proportion of our patients had been

catheterised preoperatively (74%) and thus could

not undergo uroflowmetry studies before the

operation. Due to the coronavirus disease 2019

pandemic and the associated community isolation

policy, some other patients did not complete

uroflowmetry studies. However, all IPSS data were

able to be collected via telemedicine, ensuring the

inclusion of those data in the analysis. Second, our

study did not have a sufficient number of patients

to allow subgroup analysis of patients with different

indications for transurethral WVTT; future studies

should explore treatment outcomes among patients

with different indications for transurethral WVTT.

Third, our inclusion period was prolonged, partly

due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and

partly because transurethral WVTT mainly was

regarded as a self-financed item in our centre; these

aspects led to some difficulty in accumulating a

sufficient number of patients for analysis. Finally,

this study used a single-arm design with a relatively

short follow-up period; additional studies are

needed to assess long-term treatment outcomes and

retreatment rates after transurethral WVTT under

local anaesthesia alone.

Conclusion

Transurethral WVTT is a safe and effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia in the

Chinese population. It can also be conducted in an

office setting under local anaesthesia alone, avoiding

use of the surgical theatre and its associated costs.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KL Lo, CF Ng.

Acquisition of data: KL Lo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: A Mok, ICH Ko.

Drafting of the manuscript: KL Lo, A Mok, ICH Ko.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KL Lo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: A Mok, ICH Ko.

Drafting of the manuscript: KL Lo, A Mok, ICH Ko.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, CF Ng was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2019.662). The

patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the

Declaration of Helsinki and have provided written informed

consent for all treatments and procedures and consent for

publication.

References

1. Kahokehr A, Gilling PJ. Landmarks in BPH—from aetiology to medical and surgical management. Nat Rev Urol 2014;11:118-22. Crossref

2. Gravas S, Cornu JN, Gacci M, et al. EAU guidelines on

management of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract

symptoms (LUTS), incl. benign prostatic obstruction

(BPO). 2022. Available from: https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-Neurogenic-Male-LUTS-2022.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2024.

3. Teoh JY, Chiu PK, Yee CH, et al. Prostatic artery

embolization in treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: a

systematic review. Int Urol Nephrol 2017;49:197-203. Crossref

4. Abt D, Hechelhammer L, Müllhaupt G, et al. Comparison

of prostatic artery embolisation (PAE) versus transurethral

resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic

hyperplasia: randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial.

BMJ 2018;361:k2338. Crossref

5. Roehrborn CG, Barkin J, Gange SN, et al. Five-year

results of the prospective randomized controlled prostatic

urethral L.I.F.T. study. Can J Urol 2017;24:8802-13.

6. Magistro G, Chapple CR, Elhilali M, et al. Emerging

minimally invasive treatment options for male lower

urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol 2017;72:986-97. Crossref

7. Dixon CM, Rijo Cedano E, Mynderse LA, Larson TR.

Transurethral convective water vapor as a treatment for

lower urinary tract symptomatology due to benign prostatic

hyperplasia using the Rezūm(®) system: evaluation of acute

ablative capabilities in the human prostate. Res Rep Urol

2015;7:13-8. Crossref

8. Mynderse LA, Hanson D, Robb RA, et al. Rezūm system

water vapor treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia: validation of convective

thermal energy transfer and characterization with magnetic

resonance imaging and 3-dimensional renderings. Urology 2015;86:122-7. Crossref

9. McVary KT, Gange SN, Gittelman MC, et al. Minimally

invasive prostate convective water vapor energy ablation:

a multicenter, randomized, controlled study for the

treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to

benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2016;195:1529-38. Crossref

10. McVary KT, Gittelman MC, Goldberg KA, et al. Final

5-year outcomes of the multicenter randomized sham-controlled

trial of a water vapor thermal therapy for

treatment of moderate to severe lower urinary tract

symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J

Urol 2021;206:715-24. Crossref

11. Dixon CM, Cedano ER, Pacik D, et al. Two-year results

after convective radiofrequency water vapor thermal

therapy of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Res

Rep Urol 2016;8:207-16. Crossref

12. Rowaiee R, Akhras A, Lakshmanan J, Sikafi Z, Janahi F.

Rezum therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Dubai’s

initial experience. Cureus 2021;13:e18083. Crossref

13. Pavone C, Abbadessa D, Scaduto G, et al. Sexual

dysfunctions after transurethral resection of the prostate

(TURP): evidence from a retrospective study on 264

patients. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2015;87:8-13. Crossref

14. Lee YJ, Lee JW, Park J, et al. Nationwide incidence and

treatment pattern of benign prostatic hyperplasia in Korea.

Investig Clin Urol 2016;57:424-30. Crossref

15. Hong Kong SAR Government. The 2023-24 Budget.

Budget speech. Available from: https://www.budget.gov.hk/2023/eng/budget30.html. Accessed 5 May 2024.

16. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. Hong Kong’s

domestic health accounts (DHA) 2021/22. Available from:

https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/statistics/en/dha.htm. Accessed 5 May 2024.

17. Mamoulakis C, Ubbink DT, de la Rosette JJ. Bipolar

versus monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate:

a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Eur Urol 2009;56:798-809. Crossref

18. Ulchaker JC, Martinson MS. Cost-effectiveness analysis

of six therapies for the treatment of lower urinary tract

symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clinicoecon

Outcomes Res 2018;10:29-43. Crossref

19. Tanneru K, Jazayeri SB, Alam MU, et al. An indirect

comparison of newer minimally invasive treatments for

benign prostatic hyperplasia: a network meta-analysis

model. J Endourol 2021;35:409-16. Crossref

20. Gupta N, Rogers T, Holland B, Helo S, Dynda D, McVary KT.

Three-year treatment outcomes of water vapor thermal

therapy compared to doxazosin, finasteride and

combination drug therapy in men with benign prostatic

hyperplasia: cohort data from the MTOPS trial. J Urol

2018;200:405-13. Crossref