Hong Kong Med J 2024 Apr;30(2):102–9 | Epub 26 Mar 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Hong Kong

Christina MT Cheung, MB, ChB, MRCP1; Mimi M Chang, MB, ChB, FRCP1; Joshua JX Li, MB, ChB, FHKCPath2; Agnes WS Chan, MB, ChB, MRCP1

1 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Agnes WS Chan (agneswschan@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and

toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) [hereafter, SJS/TEN] are uncommon but severe mucocutaneous

reactions. Although they have been described in

many populations worldwide, data from Hong Kong

are limited. Here, we explored the epidemiology,

disease characteristics, aetiology, morbidity, and

mortality of SJS/TEN in Hong Kong.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study included

all hospitalised patients who had been diagnosed

with SJS/TEN in Prince of Wales Hospital from 1

January 2004 to 31 December 2020.

Results: There were 125 cases of SJS/TEN during

the 17-year study period. The annual incidence was

5.07 cases per million. The mean age at onset was

51.4 years. The mean maximal body surface area of

epidermal detachment was 23%. Overall, patients in

32% of cases required burns unit or intensive care unit

admission. Half of the cases involved concomitant

sepsis, and 23.2% of cases resulted in multiorgan

failure or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

The mean length of stay was 23.9 days. The cause of

SJS/TEN was attributed to a drug in 91.9% of cases,

including 84.2% that involved anticonvulsants,

allopurinol, antibiotics, or analgesics. In most cases, patients received treatment comprising either

best supportive care alone (35.2%) or combined

with intravenous immunoglobulin (43.2%). The in-hospital

mortality rate was 21.6%. Major causes of

death were multiorgan failure and/or fulminant

sepsis (81.5%).

Conclusion: This study showed that SJS/TEN are

uncommon in Hong Kong but can cause substantial

morbidity and mortality. Early recognition, prompt

withdrawal of offending agents, and multidisciplinary

supportive management are essential for improving

clinical outcomes.

New knowledge added by this study

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are rare severe cutaneous adverse reactions in Hong Kong, with a combined annual incidence of 5.07 cases per million.

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN cause considerable burdens on the Hong Kong healthcare system due to their prolonged length of stay, high demand for intensive care, and substantial mortality.

- Clinicians should be aware of the early signs and symptoms of SJS and TEN to enable rapid recognition of the disease and prompt withdrawal of culprit drugs.

- Dedicated multidisciplinary teams should be established in tertiary centres to optimise patient outcomes.

Introduction

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic

epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are uncommon but

potentially life-threatening severe mucocutaneous

reactions characterised by extensive epidermal

necrosis and detachment. Both entities are

considered variants of a single disease continuum

and are classified according to the percentage of body

surface area (BSA) with epidermal detachment.1 2

Although SJS and TEN (hereafter, SJS/TEN) have

been described in all ethnicities worldwide,3 studies of these reactions in Hong Kong have been limited.4 5 The incidence, clinical characteristics, aetiology,

treatment regimen, morbidity, and mortality in the

territory are largely unknown. This pilot study aimed

to review cases of SJS/TEN over a 17-year period at

a tertiary referral centre in Hong Kong, and to aid

future research in Hong Kong focused on severe

cutaneous adverse reactions.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included all hospitalised patients who had been diagnosed

with SJS/TEN and were treated in Prince of Wales

Hospital (PWH), a major regional hospital under

the New Territories East Cluster (NTEC), from 1

January 2004 to 31 December 2020.

Patient identification

Patients with clinical and histological diagnoses of

SJS/TEN were identified from the Hospital Authority

database using International Classification of Diseases,

Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes

and the database of the Department of Anatomical

and Cellular Pathology of PWH, respectively.

Inclusion criteria

Diagnoses of SJS/TEN were based on consensus

guidelines.1 Patients were diagnosed with SJS,

SJS/TEN overlap, and TEN when they exhibited

epidermal detachment levels of <10%, 10% to 30%,

and >30%, respectively, with consistent histological

features (if skin biopsy was performed). Consistent

histological features were regarded as partial- to full-thickness

epidermal necrosis.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had an alternative

diagnosis, such as severe cutaneous adverse

reactions other than SJS/TEN (eg, drug reaction with

eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome/acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis/generalised bullous fixed drug eruption), erythema

multiforme major, autoimmune blistering disease,

acute graft-versus-host disease, and infections such

as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics were collected from

electronic records and, when available, hospital

case notes. The following clinical characteristics

were recorded and analysed: age at onset, sex,

ethnicity, maximal BSA of detached or detachable

skin, SCORTEN (Severity-of-Illness Score for Toxic

Epidermal Necrolysis) prognostic score,6 mucosa

involved, histology results if available, causative

drugs, time from exposure to onset, time from onset

to admission and treatment, treatment regimen,

disease complications, mortality and its cause, and

length of stay. Efforts to identify causative drugs

were guided by the ALDEN (algorithm of drug

causality for epidermal necrolysis) score,7 which

was retrospectively calculated by two independent

investigators. All clinical data were expressed as

percentages or means ± standard deviations unless

otherwise specified.

This article was written in compliance with

the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology) reporting

guidelines.

Results

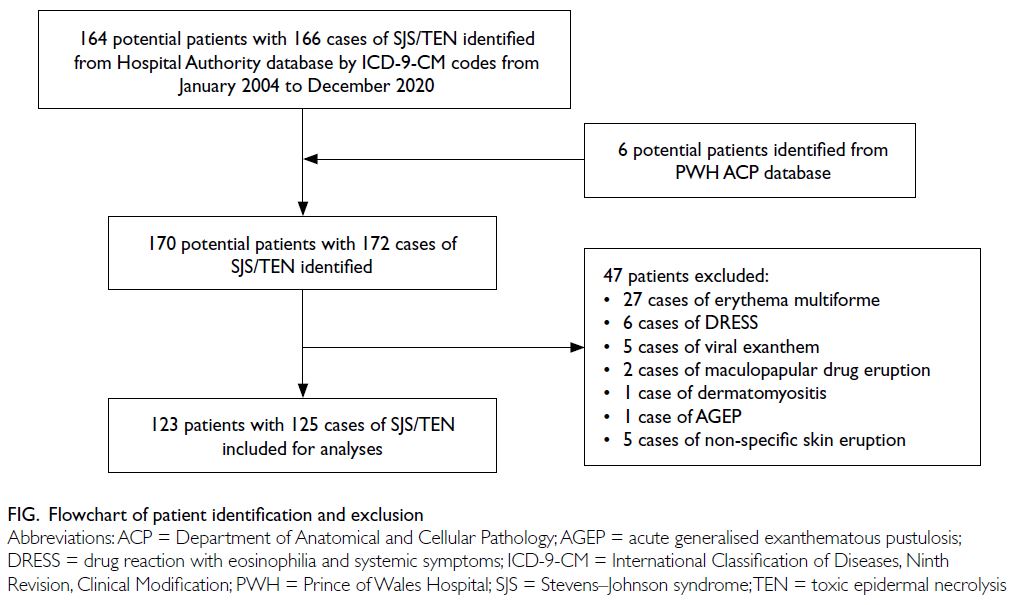

Using the International Classification of Diseases,

Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis

codes for SJS/TEN, 164 potential patients with 166

cases of SJS/TEN during the period from January

2004 to December 2020 were initially identified. Six

additional patients with SJS/TEN were identified

from the database of the Department of Anatomical

and Cellular Pathology of PWH. Forty-seven

patients were excluded due to alternative diagnoses.

In total, 123 patients with 125 cases of SJS/TEN were

included in the study (Fig).

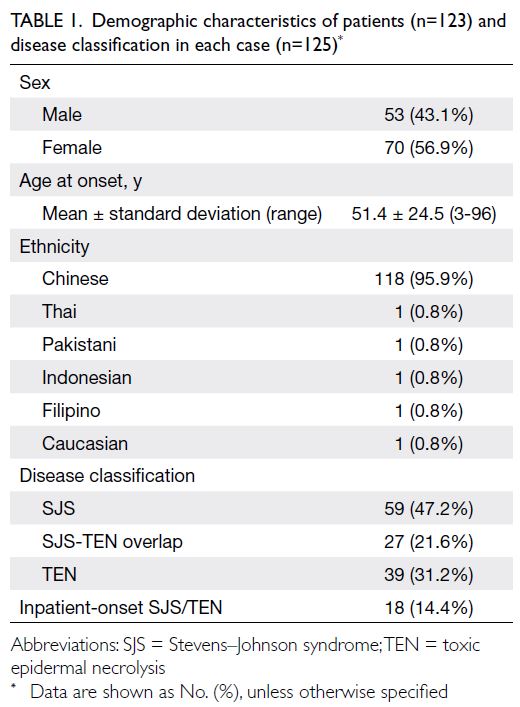

Demographic characteristics and disease

classification

Among the 123 patients with SJS/TEN, 53 were men

and 70 were women; the female-to-male ratio was

1.32:1 (Table 1). The mean age at onset was 51.4

years, and most patients were Chinese. Of the 125

cases, 59 were SJS, 27 were SJS-TEN overlap, and

39 were TEN. A small number of patients (n=18,

14.4%) were admitted for other medical issues but

developed SJS/TEN after hospitalisation.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients (n=123) and disease classification in each case (n=125)

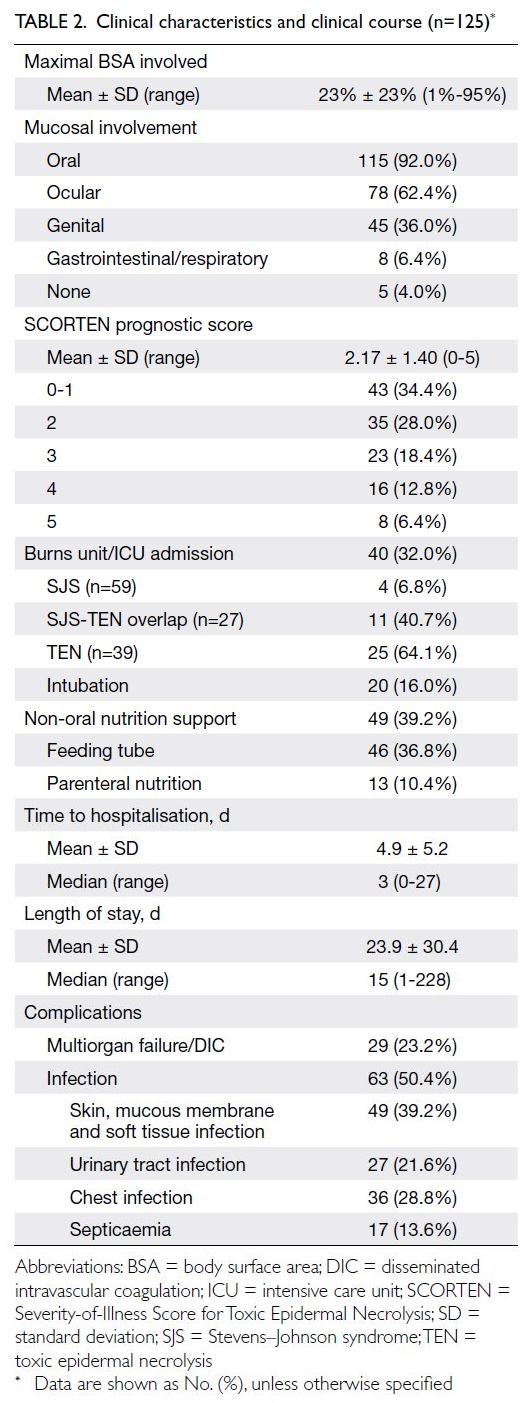

Clinical characteristics and clinical course

The mean time from disease onset to hospitalisation was 4.9 days (Table 2). Fever was present on

admission in 88 cases (70.4%). The mean maximal

BSA of epidermal detachment was 23%. Mucosal

involvement was common; only five cases (4.0%)

lacked mucosal involvement. Skin biopsy was performed in 87 cases (69.6%) and the mean SCORTEN prognostic score was 2.17.

Burns unit or intensive care unit admission was

required in 40 cases (32.0%) and half of these cases

required invasive mechanical ventilation. In total, 63

cases (50.4%) involved concomitant infection from

various sources. Multiorgan failure or disseminated

intravascular coagulation occurred in 29 cases

(23.2%). The mean length of stay in the hospital was

23.9 days (Table 2).

Aetiology

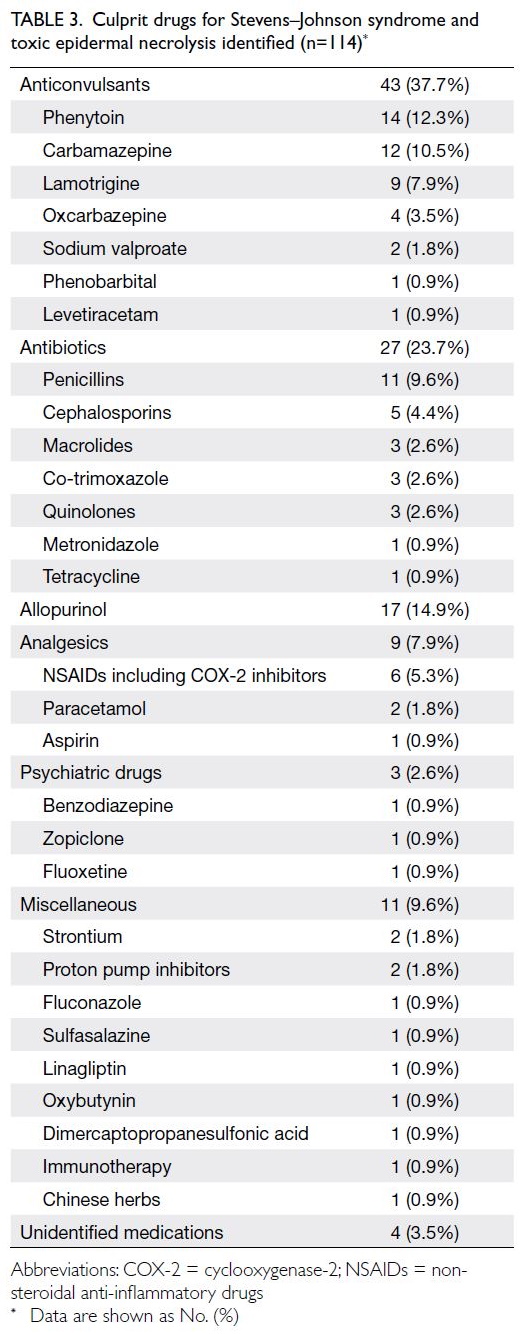

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN onset was attributed to a drug in 114 of 124 cases (91.9%); one

patient developed a second case of SJS/TEN upon

accidental re-exposure to the same culprit drug

(paracetamol). Four cases (3.2%) were caused by

infection, and no cause was identified in six cases

(4.8%). The identified culprit drugs are shown in

Table 3. The mean time from initiation of the culprit

drug to onset of SJS/TEN was 20.5 ± 16.7 days (range,

1-87; median, 15.5).

Table 3. Culprit drugs for Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis identified (n=114)

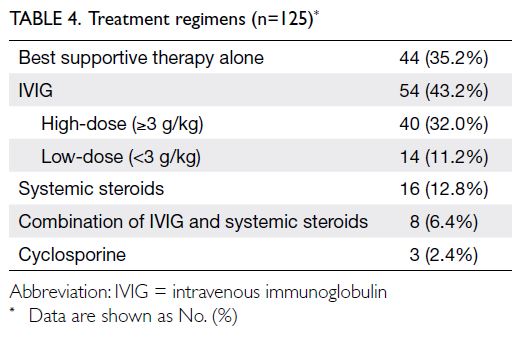

Treatment

All patients received the best supportive medical

care available. In some cases, patients received

additional treatment. The numbers and proportions

of cases treated with different regimens are shown in

Table 4. The mean time between disease onset and

active treatment initiation was 7.4 ± 6.1 days (range,

1-34; median, 6).

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was administered in 54 cases. The mean total dose of IVIG was 3.2 g/kg (range, 1.5-6; administered over

2-6 days). High-dose IVIG, defined as ≥3 g/kg, was

administered in 40 cases. Systemic steroid regimens considerably varied, with daily doses of prednisolone ranging from 20 to 120 mg (or an equivalent dose). The cyclosporine regimen was 3 mg/kg/day, tapered

over 20 to 30 days.

Mortality

There were 27 deaths in the study cohort, and the

overall mortality rate was 21.6%. The mean time from

SJS/TEN onset to death was 23.6 ± 19.0 days (range,

5-76). Most patients died from multiorgan failure

and/or fulminant sepsis (n=22, 81.5%); other causes

of death were acute coronary syndrome (n=2),

liver failure (n=1), and sudden cardiac arrest

(n=2).

The observed mortality rates were 16.9%,

22.2%, and 28.2% for SJS, SJS-TEN overlap, and

TEN, respectively. The SCORTEN-based predicted

mortality rates were 14.1%, 28.5%, and 36.9% for SJS,

SJS-TEN overlap, and TEN, respectively. Inpatient-onset

SJS/TEN had a high mortality rate of 77.8%: 14

deaths among 18 patients who developed SJS/TEN

after admission.

Discussion

Epidemiology

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN are recognised

worldwide, with several epidemiological studies

conducted in Europe and the US. In the 1990s,

Roujeau et al8 reported that the annual incidence of

TEN in France was 1.2 cases per million; during the

same period, the estimated overall annual incidences

of SJS/TEN were 1.89 cases per million in Germany9

and 4.2 cases per million in the US.10 In the past

decade, two large epidemiological studies in the US11

and United Kingdom12 revealed that the overall annual

incidences of SJS/TEN were 12.7 and 5.76 cases per

million, respectively. In contrast, the epidemiology

of SJS/TEN in Asia is not well-documented.13 In

Singapore, based on a small retrospective hospital-based

study of 20 patients with TEN, the estimated

annual incidence of TEN was 1.4 cases per million14;

in Korea, a large population-based study indicated

that the overall annual incidence of SJS/TEN was 4.9

to 6.5 cases per million.15 In the present study, there

were 125 cases of SJS/TEN during the 17-year study

period. Notably, 13 of these cases were transferred

from hospitals outside of the NTEC: one was SJS, three were SJS/TEN overlap, and nine were TEN.

The NTEC serves a population of 1.3 million.16

The estimated annual incidence of TEN alone and

combined annual incidence of SJS, SJS-TEN overlap,

and TEN were 1.36 and 5.07 cases per million,

respectively; these incidences are comparable with

findings from studies in other countries.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome is approximately

threefold more common than TEN.15 17 However,

in the current study, fewer than half of the cases

(47.2%) were SJS, whereas 31.2% were TEN. This

may be related to referral bias, whereby more

severe cases were transferred to the study hospitals,

whereas ‘milder’ cases were managed in regional

hospitals where the patients were initially admitted.

Prince of Wales Hospital is a tertiary referral centre

and one of the few hospitals in Hong Kong with

both on-site dermatologists and burns unit support.

In our cohort, 31 cases (24.8%) were transferred

from peripheral hospitals: 18 (14.4%) arrived from

hospitals within the NTEC, whereas 13 (10.4%)

arrived from hospitals outside of the NTEC.

Aetiology

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN are most often drug-induced, and a culprit drug is identified

in approximately 85% of cases.7 18 The reactions

usually occur between 7 days and 8 weeks after drug

ingestion.19 However, upon rechallenge with the

culprit drug, SJS/TEN can develop within hours.17 19

Efforts to identify causative drugs were guided by

the ALDEN score.7 In cases of SJS/TEN, the most

commonly implicated high-risk medications are

anticonvulsants, allopurinol, antimicrobials, and

oxicam non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 20

In the present study, SJS/TEN onset was attributed

to a drug in 114 of 124 cases (91.9%). The mean time

between drug initiation and SJS/TEN onset was 20.5

days. Among these 114 cases, 81.6% were caused

by the high-risk medications listed above. These

findings are comparable with previous reports.

Mortality

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN are associated with high mortality rates, with 1% to 5% in cases of SJS and 25% to 30% in cases of TEN. Survival analyses

in multinational European studies (EuroSCAR

[European Study of Severe Cutaneous Adverse

Reactions] and RegiSCAR [Registry of Severe

Cutaneous Adverse Reactions]) have indicated that

the overall mortality rate in cases of SJS/TEN is

approximately 22% to 23%.18 20 21 22 23 In Asia, reported

overall mortality rates vary from 12.3% to 25%.24 25 26 27

Sepsis leading to multiorgan failure is the most

common cause of death.21 Despite the substantial

mortality, there currently is no therapeutic regimen

with a clear benefit for patients with SJS/TEN.18 21

Considering the rarity of these diseases, it is difficult to conduct randomised trials. Early recognition,

rapid withdrawal of offending agents, and best

supportive care remain the primary components of

clinical management.

In the current study, the overall mortality rate

was 21.6%; in 81.5% of these cases, the patient died of

fulminant sepsis or multiorgan failure. These findings

are consistent with existing literature. However,

the mortality rate in cases of SJS was much higher

in the present study than in previous studies. In the

59 cases of SJS, there were 10 deaths; the mortality

rate was 16.9%. Among the 10 patients who died, six

experienced complete skin re-epithelisation before

death from other medical conditions, which include

massive duodenal ulcer bleeding, acute coronary

syndrome, metastatic lung cancer, acute liver and

renal failure due to herbs, aspiration pneumonia,

and sudden cardiac arrest. The remaining four

patients had inpatient-onset SJS; they were initially

admitted for traumatic intracranial haemorrhage,

post-hepatectomy liver failure, convulsions caused

by metastatic lung cancer, and post-stroke seizure,

respectively. These patients exhibited skin-specific

improvements but soon died of aspiration pneumonia

and acute renal failure, liver failure, metastatic lung

cancer with respiratory failure and liver failure, and sudden cardiac arrest, respectively. The high

mortality rate among patients with SJS in the present

study could be related to referral bias (as noted in

the Epidemiology subsection above); specifically,

more severe cases of SJS with co-morbidities and/or complications may have been transferred to our

tertiary centre for medical care, whereas less severe

cases of SJS might have been managed in regional

hospitals where the patients were initially admitted.

Indeed, the predicted mortality rate (based on the

SCORTEN prognostic score) among cases of SJS

in our cohort was 14%; this rate was similar to the

observed mortality rate.

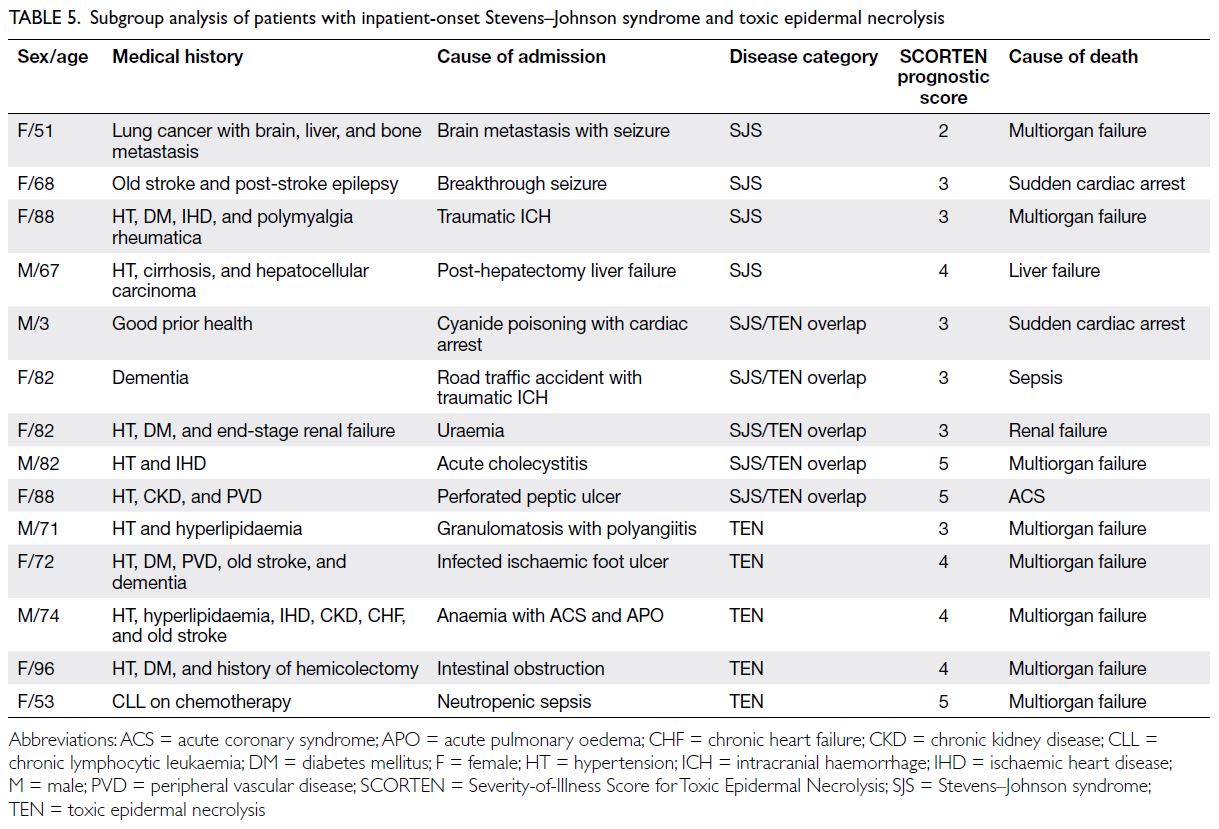

In the present study, inpatient-onset SJS/TEN had a high mortality rate (77.8%). Although

high mortality of inpatient-onset SJS/TEN was not

previously described in the literature, we speculate

that this high mortality was related to the underlying

medical conditions for which patients were initially

admitted. The clinical characteristics of the 14

patients who died are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Subgroup analysis of patients with inpatient-onset Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

In addition to high mortality, SJS/TEN were

associated with high rates of burns unit/intensive care

unit admission (32%) and prolonged length of stay

(mean=23.9 days) [Table 2], placing a considerable

burden on the public healthcare system.

Limitations and strengths

As a retrospective cohort study, the present study

had some intrinsic limitations. Some hospital case

notes (ie, from earlier in the study period) were no

longer retrievable. Clinical characteristics such as

the exact date of disease onset, precise total BSA

involved, and detailed drug history (including over-the-counter medications/medications prescribed

by private doctors) might not have been available

for some of these older cases. Skin biopsies were

performed in 70% of cases and might have been

omitted in cases of terminal illness. Many patients

with milder cases were lost to follow-up after

discharge; thus, long-term sequelae were not well-documented.

Additionally, referral bias may have been

present because PWH is a tertiary referral centre.

Such bias could have led to underestimation of

the true incidence of SJS and overestimation of

the incidence of TEN; milder cases of SJS might

have been managed in regional hospitals, whereas

more severe cases of TEN were transferred to our

centre for better care. Similarly, there may have

been overestimation of various outcome measures

including length of stay, complications, and

mortality.

Nonetheless, this study had several strengths.

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest single-centre

studies regarding SJS/TEN in Asia; it included

a homogenous group of predominantly Chinese

patients. The patients were managed by the same

dermatology team with a consistent diagnostic and

therapeutic approach throughout the study period.

Data collection was adequate, and exhaustive

evaluation of drug history was feasible for cases with

access to both electronic records and hospital case

notes. To ensure accurate identification of causative

drugs, the ALDEN score was retrospectively

evaluated by two independent dermatology doctors

during the study.

Conclusion

This is the first large study in Hong Kong to

provide data regarding the epidemiology, disease

characteristics and clinical course, aetiology,

treatment regimen, and mortality of SJS/TEN.

Although uncommon, SJS/TEN is associated with

substantial morbidity and mortality. Therefore,

in addition to increasing awareness of SJS/TEN

among patients and clinicians, efforts should be

made to optimise inpatient care among public

hospitals in Hong Kong by establishing dedicated

multidisciplinary teams that are experienced in the

management of SJS/TEN.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CMT Cheung, MM Chang.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: CMT Cheung, AWS Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: CMT Cheung, AWS Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref No.: 2017.424). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Committee due to the

retrospective nature of the research.

References

1. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L,

Roujeau JC. Clinical classification of cases of toxic

epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and

erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:92-6. Crossref

2. Roujeau JC. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic

epidermal necrolysis are severity variants of the same

disease which differs from erythema multiforme. J

Dermatol 1997;24:726-9. Crossref

3. Roujeau JC, Chosidow O, Saiag P, Guillaume JC. Toxic

epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome). J Am Acad

Dermatol 1990;23:1039-58. Crossref

4. Ying S, Ho W, Chan HH. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: 10

years experience of a burns centre in Hong Kong. Burns

2001;27:372-5. Crossref

5. Yeung CK. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

[dissertation]. Queen Mary Hospital, The University of

Hong Kong; 2004.

6. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, Roujeau JC,

Revuz J, Wolkenstein P. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness

score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol

2000;115:149-53. Crossref

7. Sassolas B, Haddad C, Mockenhaupt M, et al. ALDEN,

an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis:

comparison with case-control analysis. Clin Pharmacol

Ther 2010;88:60-8. Crossref

8. Roujeau JC, Guillaume JC, Fabre JP, Penso D, Fléchet ML,

Girre JP. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome).

Incidence and drug etiology in France, 1981-1985. Arch

Dermatol 1990;126:37-42. Crossref

9. Rzany B, Mockenhaupt M, Baur S, et al. Epidemiology

of erythema exsudativum multiforme majus, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis

in Germany (1990-1992): structure and results of a

population-based registry. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:769-73. Crossref

10. Chan HL, Stern RS, Arndt KA, et al. The incidence of

erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and

toxic epidermal necrolysis. A population-based study with

particular reference to reactions caused by drugs among

outpatients. Arch Dermatol 1990;126:43-7. Crossref

11. Hsu DY, Brieva J, Silverberg NB, Silverberg JI. Morbidity

and mortality of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic

epidermal necrolysis in United States adults. J Invest

Dermatol 2016;136:138797. Crossref

12. Frey N, Jossi J, Bodmer M, et al. The epidemiology of

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

in the UK. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137:1240-7. Crossref

13. Lee HY, Martanto W, Thirumoorthy T. Epidemiology of

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

in Southeast Asia. Dermatologica Sinica 2013;31:217-20. Crossref

14. Chan HL. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in Singapore, 1989

through 1993: incidence and antecedent drug exposure.

Arch Dermatol 1995;131:1212-3. Crossref

15. Yang MS, Lee JY, Kim J, et al. Incidence of Stevens–Johnson

syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a nationwide

population-based study using national health insurance

database in Korea. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165933. Crossref

16. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. New Territories East Cluster biennial report 2018-2020. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/ntec/clusterreport/clusterreport2018-20/index.html. Accessed 8 Feb 2024.

17. Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal

necrolysis: Part I. Introduction, history, classification,

clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and

immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:173.

e1-13; quiz 185-6. Crossref

18. Creamer D, Walsh SA, Dziewulski P, et al. UK guidelines

for the management of Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults 2016. J Plast Reconstr

Aesthet Surg 2016;69:e119-53. Crossref

19. Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, et al. Medication use and the risk of Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1600-7. Crossref

20. Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis:

assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently

marketed drugs. The EuroSCAR study. J Invest Dermatol

2008;128:35-44. Crossref

21. Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal

necrolysis: Part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis,

differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am

Acad Dermatol 2013;69:187.e1-16; quiz 203-4. Crossref

22. Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions

to drugs. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1272-85. Crossref

23. Sekula P, Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, et al. Comprehensive

survival analysis of a cohort of patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest

Dermatol 2013;133:1197-204. Crossref

24. Barvaliya M, Sanmukhani J, Patel T, Paliwal N, Shah H,

Tripathi C. Drug-induced Stevens–Johnson syndrome

(SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and SJS-TEN

overlap: a multicentric retrospective study. J Postgrad Med

2011;57:115-9. Crossref

25. Roongpisuthipong W, Prompongsa S, Klangjareonchai T.

Retrospective analysis of corticosteroid treatment in

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and/or toxic epidermal

necrolysis over a period of 10 years in Vajira Hospital,

Navamindradhiraj University, Bangkok. Dermatol Res

Pract 2014;2014:237821. Crossref

26. Suwarsa O, Yuwita W, Dharmadji HP, Sutedja E. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Dr

Hasan Sadikin General Hospital Bandung, Indonesia from

2009-2013. Asia Pac Allergy 2016;6:43-7. Crossref

27. Lee HY, Fook-Chong S, Koh HY, Thirumoorthy T, Pang SM.

Cyclosporine treatment for Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: retrospective analysis of a

cohort treated in a specialized referral center. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2017;76:106-13. Crossref