Hong Kong Med J 2024 Apr;30(2):90–3 | Epub 10 Apr 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

Call to action: bridging gaps in lipid management

in Hong Kong

Bryan PY Yan, MD, FRCP1; Kui Kai Lau, DPhil, FRCP2; Andrea OY Luk, MD, FRCP3; Martin CS Wong, MD, MPH4,5

1 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Editor-in-Chief, Hong Kong Medical Journal

Corresponding author: Dr Bryan PY Yan (bryan.yan@cuhk.edu.hk)

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Hong Kong

Cardiovascular disease is the third leading cause

of death in Hong Kong, contributing to 13% of

all deaths in 2020.1 According to the Hong Kong

Population Health Survey conducted between

2020 and 2022, the prevalence of high blood

cholesterol among individuals aged 15 to 84 years

in the Hong Kong general population increased

from 8.4% in 2003/20042 to 51.9% in 2022.3 Low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) has been

recognised as one of the most important modifiable

risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular

disease (ASCVD).4 Accordingly, optimal LDL-C

management is essential for reducing the incidence of

and mortality from ASCVD. Despite the availability

of effective and safe lipid-lowering therapies (LLTs)

and guidelines for managing elevated LDL-C and

other lipids, implementation remains a key challenge

in clinical practice.

Advancements in lipid-lowering therapies

A lower LDL-C level is highly beneficial because of

the direct correlation between the absolute reduction

in LDL-C level and reduced cardiovascular risk,

such that an incremental reduction in LDL-C level

leads to a proportional reduction in the number of

cardiovascular events.5 Statins are well-established

as effective LLTs; this recognition has been extended

to other non-statin therapies, including proprotein

convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors

(PCSK9is), ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, evinacumab,

and inclisiran.6 7 Clinical trials have demonstrated

that PCSK9is effectively lower LDL-C levels, thereby

surpassing previous recommendations (high risk:

<2.6 mmol/dL; very high risk: <1.8 mmol/dL) to

offer additional cardiovascular benefits to patients

(particularly those with high or very high ASCVD

risk) who failed to meet their target LDL-C goal despite maximally tolerated high-intensity statin therapy.6 8

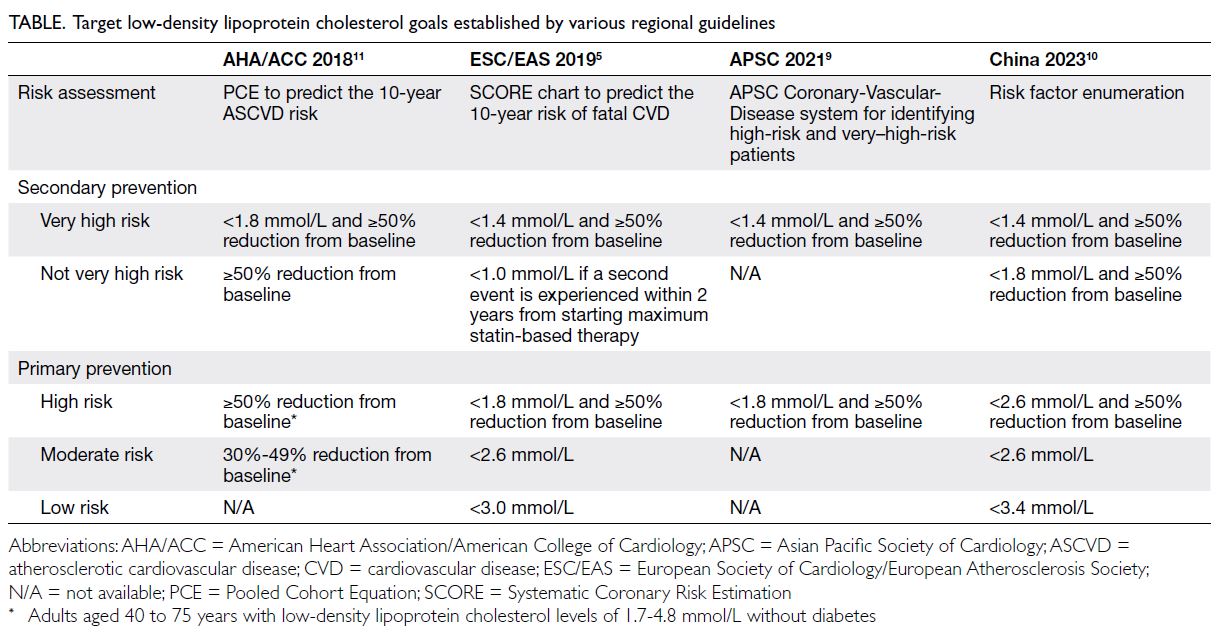

Adapting the latest evidence into current guidelines

The European Society of Cardiology and European

Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) revised their

guidelines in 2019 to integrate recent evidence

concerning ASCVD prevention.5 These updates

include a more aggressive approach with new LDL-C

targets across all cardiovascular risk categories,

as well as recommendations for lipid-lowering

strategies. Since these updates, other cardiology

societies (Table)1 5 10 11 and medical associations12 13

have also begun to recommend achieving the lowest

possible LDL-C levels, especially for patients with

very high ASCVD risk.

The 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines recommend

the following LDL-C targets for the prevention

of ASCVD in very high- and high-risk patients:

<1.4 mmol/L and <1.8 mmol/L (and 50% reduction

from baseline), respectively.5 Consistent with these

recommendations, the 2024 American Diabetes

Association guidelines recommend that patients

with diabetes aged 40 to 70 years receive moderate-intensity

statins, and such patients with one or

more ASCVD risk factors receive high-intensity

statins, to achieve LDL-C level <1.8 mmol/L and ≥50%

reduction from baseline.12 Statin therapy should

also be considered for young adults aged 20 to 39

years, depending on their existing risk factors.12

The American Heart Association/American Stroke

Association guidelines recommend a target LDL-C level of <1.8 mmol/L for patients who have experienced

transient ischaemic attack/ischaemic stroke with

atherosclerotic disease.13

If there is inadequate LDL-C reduction with

maximally tolerated statins, the addition of non-statin

options (eg, PCSK9is or ezetimibe) can be

considered according to the extent of reduction

required to reach the LDL-C goal.5 7 9 10 11 12 13

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol target achievement remains challenging in Hong Kong

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol management in

Hong Kong has gradually improved, but considerable

gaps in care persist. A territory-wide study conducted

between 2016 and 2021 revealed poor achievement

of LDL-C target goals among patients hospitalised

for acute coronary syndrome.14 The study showed low

rates of prescription for high-intensity statins (53%)

and combination LLTs (1.3%-3.8%) at discharge; LLT

and statin treatments were rarely intensified after

discharge.14 Notably, approximately 22% of patients

did not undergo follow-up lipid profile assessment

after discharge.14 This lack of follow-up has been

identified as an independent risk factor for all-cause

death and cardiovascular-related death.14

A separate study involving over 700 000

patients revealed gross underutilisation of statins

among patients with diabetes in Hong Kong,

such that most of this population failed to meet

LDL-C targets.15 Importantly, women and younger

individuals were particularly undertreated,

highlighting the need to address these age and sex

disparities in lipid management.15 Consistent with current evidence,5 a large cohort of local patients with ischaemic stroke (with or without significant large artery atherosclerosis) demonstrated that

the achievement of a target LDL level <1.8 mmol/L was

associated with a reduced risk of subsequent major

adverse cardiovascular events.16

Outdated recommendations in local settings

can hinder optimal lipid management. As a result,

physicians may fail to initiate appropriate LLT,

prioritise regular monitoring, or provide appropriate

follow-up care to assess treatment efficacy. Patients

may not recognise the dangers of elevated LDL-C

levels or understand the importance of lifestyle

modification and medication adherence, leading to

suboptimal outcomes.

Call to action: bridging gaps in lipid management

The International Atherosclerosis Society issued a call to action for improvements in lipid

management, based on a multinational survey that

involved 1758 physicians comprising cardiologists,

endocrinologists, neurologists/stroke specialists,

nephrologists, and general medicine practitioners

from Japan, Germany, Colombia and the Philippines;

the survey was designed to identify knowledge gaps

in clinical practice.17 The results highlighted three

major gaps in beliefs and behaviour across the four

countries: (1) physicians lacked clear guidance

concerning the management of higher-risk patients

who may benefit from aggressive LLT; (2) although

most physicians believed that they followed guideline

recommendations, only half knew the LDL-C target

for high-risk patients, and more than one-third had

no opinion concerning the safety of low LDL-C levels;

and (3) physicians were unsure of the potential effects

of statins on cognitive, renal, and hepatic functions, as well as the increased risk of haemorrhagic stroke

associated with low LDL-C levels.17 Taken together,

these findings highlighted key areas for enhanced

education and research efforts to bridge gaps in

lipid management.17 Physicians’ limited familiarity

with the rapidly changing guidelines hinders optimal

LDL-C management.

The Hong Kong Cardiovascular Task Force

published a consensus statement regarding ASCVD

prevention in 2016, based on the 2011 ESC/EAS

guidelines and the 2013 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines.18

Although the consensus is valuable, it primarily

constitutes expert opinion and lacks endorsement

from any medical societies. Additionally, although

various international societies have established

guidelines for optimal lipid management, differences

among these recommendations (eg, pharmacological

treatment, lifestyle modification, and therapeutic

targets) may lead to confusion and uncertainty

among primary care physicians regarding the best

approach.19

Efforts to bridge current gaps in lipid

management in Hong Kong will require identifying

local therapeutic limitations and barriers to

optimising lipid management among physicians

and patients. Based on knowledge of these issues,

a consensus among local experts (ie, cardiologists,

endocrinologists, neurologists, nephrologists,

internists, general practitioners, nutritionists,

and other healthcare specialists) can be achieved

to provide practical recommendations that are

consistent with international guidelines and

adapted to local clinical practice.11 Considering the

complexities and time involved in developing local

guidelines, a practical course of action would involve

local medical societies across various specialties

collaborating to issue a joint statement that

recommends the adoption of appropriate guidelines,

thereby ensuring a more cohesive and unified

approach to lipid management in Hong Kong.

Local recommendations should also address

pertinent issues, such as greater adherence to

established guidelines—specifically, by encouraging

the prompt initiation and intensification of statin

therapy in eligible patients. Because the overall

ASCVD risk assessment is the basis for treatment

decisions in patients with dyslipidaemia,5 7 9

appropriate tools—adapted to the local population—should be used in routine clinical practice to ensure

that patients are adequately assessed and managed.

Additionally, the benefits of long-term adherence

to LLT should be consistently and effectively

communicated to patients.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript, approved the final version for publication, and take full responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

KK Lau has received grants from the Croucher Foundation,

Research Fund Secretariat of the Food and Health Bureau,

Innovation and Technology Bureau, Research Grants

Council, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, and Pfizer, as

well as consultation fees from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim,

Daiichi Sankyo, and Sanofi, all unrelated to the submitted

work. AOY Luk has served as a member of advisory panels

for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Sanofi

and has received research support from Amgen, Asia

Diabetes Foundation, Bayer, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim,

Lee’s Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi,

Sugardown Ltd., and Takeda, unrelated to the submitted

work. As editors of the journal, BPY Yan, KK Lau and MCS

Wong were not involved in the peer review process.

Acknowledgement

Medical writing support was provided by Veronica Yap and Analyn Lizaso of Weber Shandwick Health HK.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Heart diseases. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/healthtopics/content/25/57.html. Accessed 23 Jan 2024.

2. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government and Department of Community

Medicine, University of Hong Kong. Population Health

Survey 2003/2004. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/report_on_population_health_survey_2003_2004_en.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2024.

3. Non-Communicable Disease Branch, Centre for Health

Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Population Health Survey 2020-22 (Part II).

Published April 2023. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_2_report_eng_rectified.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2024.

4. Borén J, Chapman MJ, Krauss RM, et al. Low-density

lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease:

pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: a

consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis

Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2313-30. Crossref

5. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS

Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid

modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J

2020;41:111-88. Crossref

6. Furtado RH, Giugliano RP. What lessons have we learned

and what remains to be clarified for PCSK9 inhibitors?

A review of FOURIER and ODYSSEY outcomes trials.

Cardiol Ther 2020;9:59-73. Crossref

7. Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, et al. 2022

ACC Expert consensus decision pathway on the role of

nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the

management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk:

a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution

Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:1366-418. Crossref

8. Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2999-3058. Crossref

9. Koh N, Ference BA, Nicholls SJ, et al. Asian Pacific

Society of Cardiology consensus recommendations on

dyslipidaemia. Eur Cardiol 2021;16:e54. Crossref

10. Li JJ, Zhao SP, Zhao D, et al. 2023 Chinese guideline for lipid management. Front Pharmacol 2023;14:1190934. Crossref

11. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force

on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol

2019;73:e285-350. Crossref

12. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice

Committee. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk

management: standards of care in diabetes—2024.

Diabetes Care 2024;47(Suppl 1):S179-218. Crossref

13. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021

Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with

stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from

the American Heart Association/American Stroke

Association. Stroke 2021;52:e364-467. Crossref

14. Sun H, Lai A, Tan GM, Yan B. Therapeutic gaps in

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol management have

narrowed over time but remain wide: a Hong Kong–wide

study of 40,141 acute coronary syndrome patients from

2016 to 2021. Presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2023; 2023 Aug

25-28; Amsterdam: Netherlands. Crossref

15. Wu H, Lau ES, Yang A, et al. Trends in diabetes-related

complications in Hong Kong, 2001-2016: a retrospective

cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020;19:60. Crossref

16. Lau KK, Chua BJ, Ng A, et al. Low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol and risk of recurrent vascular events in Chinese

patients with ischemic stroke with and without significant

atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e021855. Crossref

17. Barter PJ, Yamashita S, Laufs U, et al. Gaps in beliefs and

practice in dyslipidaemia management in Japan, Germany,

Colombia and the Philippines: insights from a web-based

physician survey. Lipids Health Dis 2020;19:131. Crossref

18. Cheung BM, Cheng CH, Lau CP, et al. 2016 consensus

statement on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular

disease in the Hong Kong population. Hong Kong Med J

2017;23:191-201. Crossref

19. Singh M, McEvoy JW, Khan SU, et al. Comparison of

transatlantic approaches to lipid management: the AHA/ACC/Multisociety Guidelines vs the ESC/EAS Guidelines.

Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95:998-1014. Crossref