Hong Kong Med J 2023 Dec;29(6):564–5 | Epub 23 Aug 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Survival of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest following a return of spontaneous circulation beyond 30 minutes

KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; KL Chan, MB, ChB, MRCPCH1; WF Hui, MB, ChB, MRCPCH1; KT Chau, MB, BS, FRCPCH1; SY Qian, MD2

1 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

To the Editor—There was a local blog report in Hong Kong of a 5-year-old girl who experienced

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) with return

of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after 31 minutes

and was discharged with an implantable cardioverter

defibrillator.1 However, ROSC within 30 minutes is

usually required for a favourable outcome.2 3

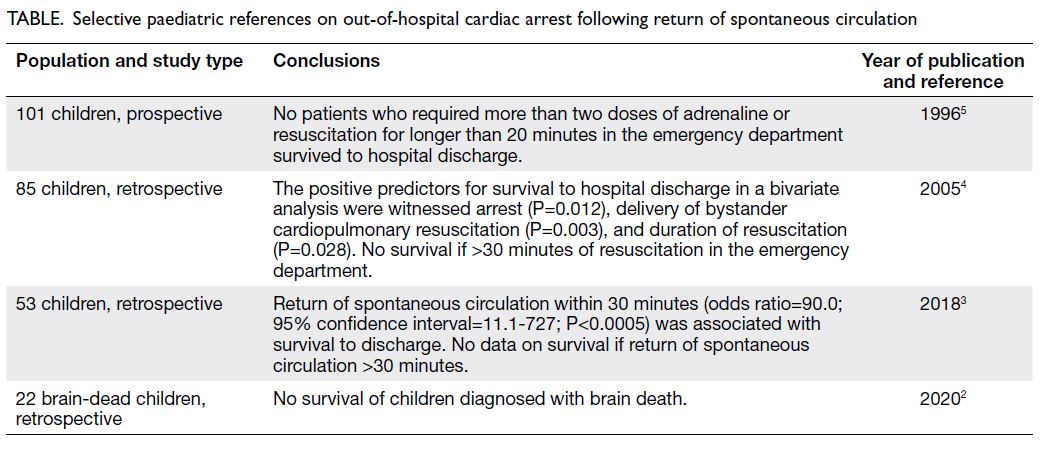

We performed a literature search to determine

the longest time to ROSC and survival rates of OHCA

in children (Table). Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

in children has a poor prognosis and prolonged

in-hospital resuscitation beyond 30 minutes does

not improve survival.3 Predictors of survival to

discharge include witnessed arrest (P=0.012),

delivery of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(P=0.003), and duration of resuscitation (P=0.028).

However, none who received more than 30 minutes

of in-hospital resuscitation survived.4 A prospective

study found that no patients who required >2 doses

of adrenaline or in-hospital resuscitation for longer

than 20 minutes survived to discharge.5 However, it

is possible that ROSC beyond 30 minutes has not

been reported, or that this case is an exception.

Table. Selective paediatric references on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest following return of spontaneous circulation

Evidence suggests that either death or a poor

outcome is inevitable if OHCA occurs more than 30

minutes from the nearest healthcare facility or the

resuscitation exceeds 30 minutes.6 7 A 2017 study

reported that the survival rate to discharge in Hong

Kong was only 2.3%, which was considerably lower

than the global survival rate in adults (8.8%).8 9 As OHCA in children has not been evaluated in Hong Kong until 2018,3 and prospective evaluation of OHCA in children has not yet been conducted, we concur with Wu10 who suggested the establishment of an OHCA registry.

Many parents and family members who are

present during a resuscitation attempt would want

to be in attendance if their child were likely to die,

and this experience can help with later grieving

without impacting on the resuscitation process. If

appropriate, family-centred care should be practised

and parents should be involved in the decision-making

process.6 As paediatricians, although our

patient is the child, his/her family members are also

important—after all, if the child passes away, it is

the family who must shoulder the lifelong emotional

burden.

In summary, OHCA in children has a poor

prognosis and prolonged resuscitation does not

improve survival or outcome.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the drafting of the letter and critical revision for important intellectual content. All

authors approved the final version for publication and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts

of interest.

Funding/support

This letter received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Philip. 死去31分鐘的女兒 [in Chinese]. Available from: https://todecidenow.wordpress.com/2021/01/31/死去31分鐘的女兒!/. Accessed 24 Jul 2023.

2. Hon KL, Tse TT, Au CC, et al. Brain death in children: a retrospective review of patients at a paediatric intensive care unit. Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:120-6. Crossref

3. Law AK, Ng MH, Hon KL, Graham CA. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the pediatric population in Hong Kong: a 10-year review at a university hospital. Pediatr Emerg Care 2018;34:179-84. Crossref

4. Tham LP, Chan I. Paediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: epidemiology and outcome. Singapore Med J 2005;46:289-96.

5. Schindler MB, Bohn D, Cox PN, et al. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac or respiratory arrest in children. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1473-9. Crossref

6. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric

Emergency Medicine Committee; National Association

of EMS Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics

Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; Fallat ME.

Withholding or termination of resuscitation in pediatric

out-of-hospital traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest.

Pediatrics 2014;133:e1104-16. Crossref

7. American Heart Association. Highlights of the 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR and ECC. 2020. Available from: https://cpr.heart.org/-/media/cpr-files/cpr-guidelines-files/highlights/hghlghts_2020_ecc_guidelines_english.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr 2021.

8. Fan KL, Leung LP, Siu YC. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Hong Kong: a territory-wide study. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:48-53. Crossref

9. Yan S, Gan Y, Jiang N, et al. The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2020;24:61. Crossref

10. Wu WY. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the importance of a registry. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:176-7. Crossref