Hong Kong Med J 2023 Dec;29(6):489–97 | Epub 19 Dec 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Moral distress and psychological status among healthcare workers in a newly established paediatric intensive care unit

WL Cheung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; WF Hui, MB, ChB, MRCPCH1; Judith JM Wong, MBBChBAO, MRCPCH2; JH Lee, MB, BS, MRCPCH2; SC Kwok, BNur3; Patrick Ip, MB, BS, MD4

1 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Children’s Intensive Care Unit, Department of Paediatric Subspecialties, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

3 Nursing Services Division, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Healthcare workers in intensive care

units often experience moral distress, depression,

and stress-related symptoms. These conditions

can lower staff retention and influence the quality

of patient care. This study aimed to evaluate the

prevalence of moral distress and psychological status

among healthcare workers in a newly established

paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in Hong Kong.

Methods: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey

was conducted in the PICU of the Hong Kong

Children’s Hospital; healthcare workers (doctors,

nurses and allied health professionals) were invited

to participate. The Revised Moral Distress Scale

(MDS-R) Paediatric Version and Depression

Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 items were used to

assess moral distress and psychological status,

respectively. Demographic characteristics were

examined in relation to moral distress, depression,

anxiety, and stress scores to identify risk factors for

poor psychological outcomes. Correlations of moral

distress with depression, anxiety, and stress were

examined.

Results: Forty-six healthcare workers completed

the survey. The overall median MDS-R moral

distress score was 71. Nurses had a significantly

higher median moral distress score, compared with

doctors and allied health professionals (102 vs 47 vs

20). Nurses also had the highest median anxiety and

stress scores (11 and 20, respectively). Moral distress scores were correlated with depression (r=0.445;

P=0.002) and anxiety scores (r=0.417; P<0.05).

Healthcare workers intending to quit their jobs had

significantly higher moral distress scores (P<0.05).

Conclusions: Among PICU healthcare workers,

nurses had the highest level of moral distress. Moral

distress was associated with greater depression,

anxiety, and intention to quit. Healthcare workers

need support and a sustainable working environment

to cope with moral distress.

New knowledge added by this study

- Among paediatric intensive care unit healthcare workers, nurses had the highest moral distress scores.

- Moral distress was associated with greater depression, anxiety, and intention to quit.

- Healthcare workers need support and a sustainable working environment to cope with moral distress.

- Considering the high levels of moral distress experienced by nurses as well as the substantial moral distress in relation to end-of-life care, coping strategies should target nurses and focus on end-of-life education.

Introduction

Paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) are highly

specialised workplaces that support children with

critical illnesses and their caregivers. Advances in

paediatric critical care have significantly improved

survival among critically ill children, although this

improvement has also led to higher rates of morbidity,

more disabilities, and longer hospital stays.1 2 3 4 5 These changes have resulted in potentially conflicting views

regarding expectations and treatment goals among

healthcare workers and patients’ families, increasing

the incidence of moral distress among healthcare

workers.6

Moral distress is a term that refers to

experiences of frustration and failure arising from

healthcare workers’ attempts to fulfil their moral obligations to patients, families, and the public.7 8

In an intensive care setting, healthcare workers

frequently encounter ethical issues. Moral distress

arises when a healthcare worker has determined

the right course of action but cannot follow it

because of internal or external constraints (eg,

limited resources, institutional policies, or family

preferences).9 Moral distress has been identified

among healthcare workers in both adult ICUs and

PICUs.10 11 It is associated with greater experience

and lower staff retention.12

Depression and stress-related symptoms

are common in healthcare workers, particularly

among ICU staff.13 14 Studies have shown that

these symptoms can ultimately impair patient care

quality.15 16 Thus far, most literature regarding moral

distress has been published in Western countries;

the concept of moral distress is not well-known

outside of the Western world.17 To our knowledge,

there have been few analyses of moral distress and

psychological status among healthcare workers in

non-Western PICUs. Factors that can influence

the level and type of moral distress include cultural

backgrounds; beliefs of the patient, their family, and

the clinical team; and differences among healthcare

systems. Hong Kong is a multicultural city influenced

by both Eastern and Western cultures; challenges in

this setting may be unique. This study assessed moral

distress prevalence and psychological status among

PICU healthcare workers in Hong Kong.

Methods

Study population and study design

This prospective single-centre cross-sectional study

was conducted from June to July 2020 in the six-bed

tertiary PICU of the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital

(HKCH), which began operation at the end of March

2019. The HKCH is the only dedicated paediatric

oncology centre in the region, and most PICU

admissions (54%) during the study period involved

patients with cancer.

Study participants were healthcare workers

involved in direct clinical care within the HKCH

PICU, including doctors, nurses, and allied health

professionals (ie, physiotherapists, occupational

therapists, speech therapists, pharmacists, and

dietitians). Healthcare workers were excluded if

they had <3 months of critical care experience in the

PICU or were temporarily on leave from the PICU

during the study period. The survey was distributed

to all eligible healthcare workers in the HKCH PICU

during working hours within the study period.

Data collection and outcome measurement

The survey included two validated instruments

(Revised Moral Distress Scale [MDS-R] Paediatric

Version and Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale–21

items [DASS-21]) to measure levels of moral stress,

depression, anxiety, and stress in all participants.18 19

The participants’ demographic details were

also collected. The survey explored job-quitting

intentions related to moral distress or other reasons.

It was piloted with two HKCH PICU staff members;

questions were refined based on feedback from them.

The final survey was paper-based. An email was

sent to all participants before study commencement

with information regarding the aim and details

of the study. The survey was distributed by hand,

and all copies were collected in a sealed box after

completion. To ensure anonymity, the survey did not

contain any identifiers.

Moral distress, the main outcome of the study,

was measured using the validated paediatric version

of the MDS-R (online supplementary Appendix 1).18

It consists of 21 items describing predetermined

potentially morally distressing situations. There are

five predetermined categories of situations: end-of-life

care and quality of life, poor communication,

staffing and material resources, hierarchies of

decision making, and witnessing unethical behaviour.

Each item on the MDS-R is scored according to the

frequency and intensity that a healthcare worker

experienced, using a Likert scale that ranges from 0 to

4. If a specific situation has never been experienced,

participants are asked to indicate how disturbing

the situation would be if they encountered it in their

workplace. The frequency and intensity scores are

then multiplied to produce an overall score for each item. The total moral distress score is the sum of

the 21 overall scores for each item, ranging from 0

to 336. The English version of this instrument was

used.

Psychological status was assessed using the

DASS-21 (online supplementary Appendix 2).19 It is

a set of three self-reporting subscales that measure

participants’ emotional states: depression, anxiety,

and stress. Each scale contains seven items for each

emotional state. Each item is scored on a four-point

Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘Did not apply to

me at all’) to 3 (‘Applied to me very much or most

of the time’). The total score for each emotional

state is the sum of the subscale scores multiplied

by 2. Depression, anxiety, or stress was considered

present if the relevant scores exceeded the normal

cut-off. The emotional state was categorised as mild,

moderate, severe, or extremely severe, based on

published cut-offs. The English and Chinese versions

of this instrument were used; both language versions

have been validated.19 20

Data analysis

Outcome measures were demographic data and the

levels of moral distress, depression, anxiety, and stress.

Data were expressed using median (interquartile

range [IQR]) for continuous variables and count

(percentage) for categorical variables. Results of

the MDS-R and DASS-21 were compared among

doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals using

the Chi squared test, Kruskal-Wallis test, or Cohen’s

d. Correlations between participant variables and

outcome measures were evaluated using Spearman’s

rank correlation coefficient. P values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis

was performed using SPSS (Windows version 26.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Results

In total, 46 of 56 healthcare workers in the PICU

completed the survey; the response rate was 82%.

On one survey, the moral distress section was

incomplete; that survey was excluded from the

analysis of moral distress.

Demographic characteristics

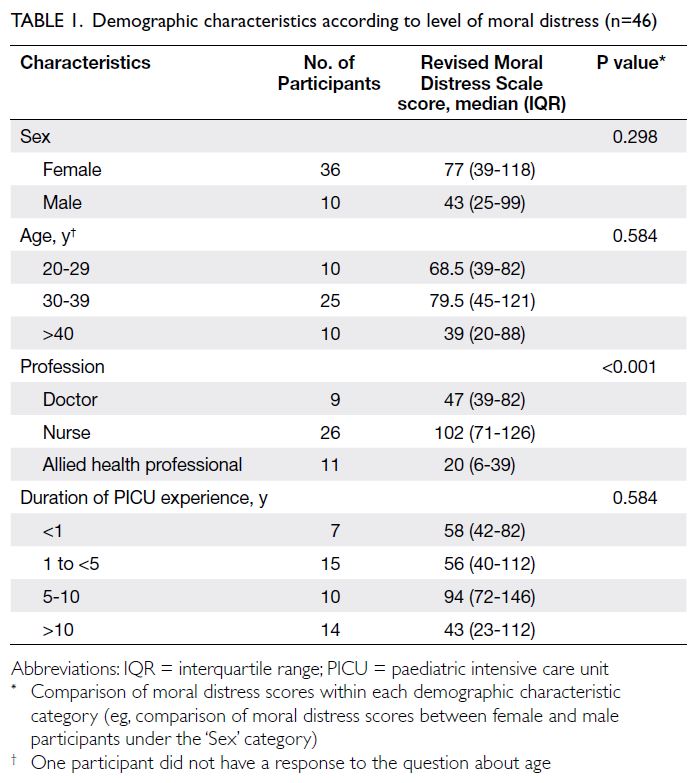

Most participants were women (n=36, 78%) and were aged ≥30 years (n=35, 76%). More than

half of the participants were nurses (n=26, 57%).

Approximately half of the participants (n=24,

52%) had >5 years of PICU experience. Detailed

participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Moral distress

The median MDS-R score was 71 (IQR=34-115). There was a significant difference in MDS-R score

among the three professions (P<0.001). Doctors and nurses had significantly higher MDS-R scores,

compared with allied health professionals (P<0.05).

Nurses had the highest median MDS-R score (102,

IQR=71-126), whereas allied health professionals

had the lowest (20, IQR=6-39). There were no

significant differences in MDS-R score according to

sex, age, or duration of PICU experience (Table 1).

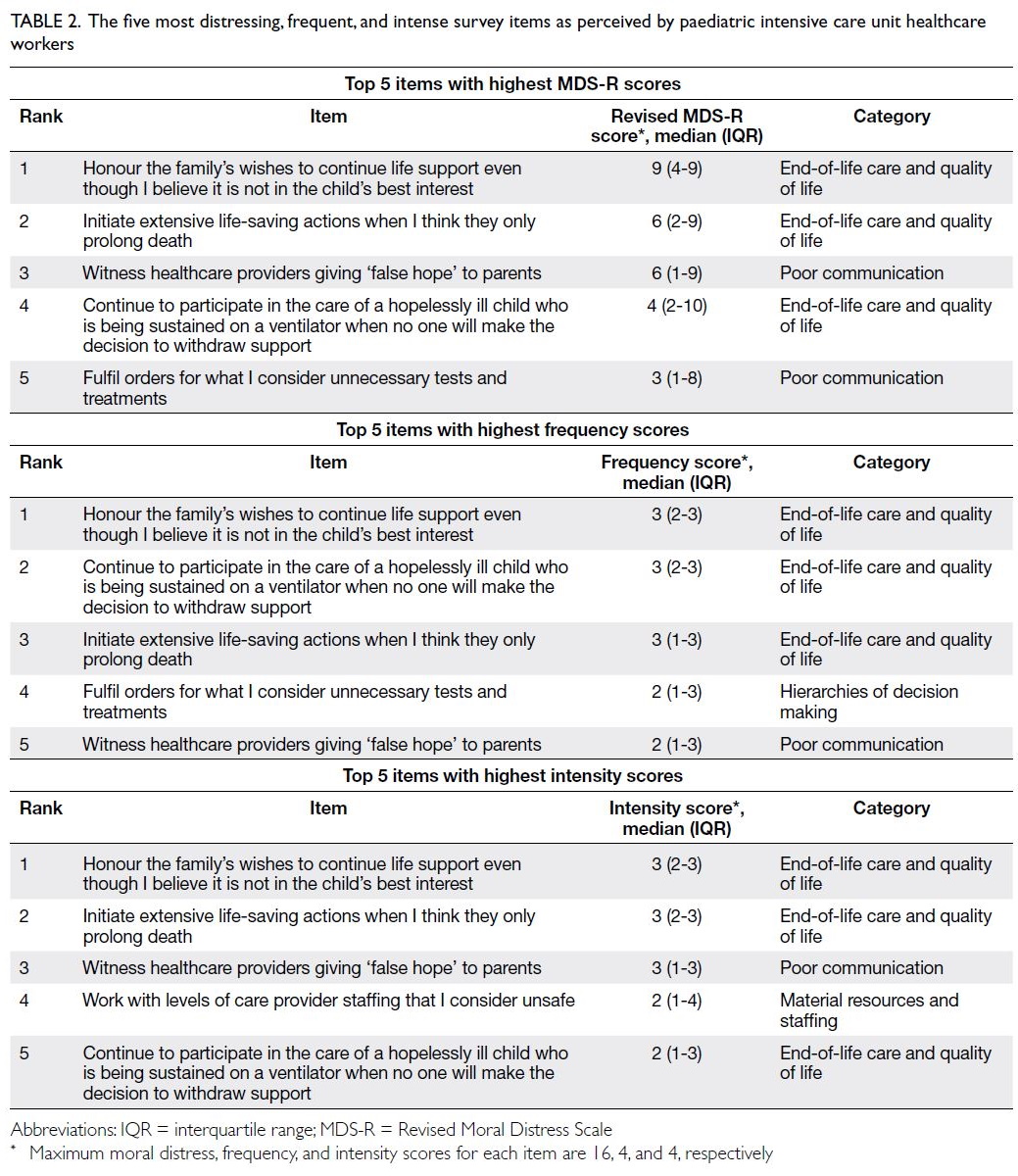

Among the 21 items on the MDS-R, the most

morally distressing item was related to end-of-life

care and quality of life: ‘Honour the family’s wishes

to continue life support even though I believe it is

not in the child’s best interest’. This item also scored

highest in frequency and intensity among the 21

items. All three groups of health professionals

ranked this item as the most morally distressing

situation in the clinical setting. The second most

morally distressing item was also related to end-of-life

care and quality of life: ‘Initiate extensive life-saving

actions when I think they only prolong death’.

This item also consistently scored high in frequency

and intensity (Table 2). Situations involving poor

communication constituted the remaining three

most morally distressing items in this study. The top

five most morally distressing items, as well as the top

five items with the highest frequency and intensity,

are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. The five most distressing, frequent, and intense survey items as perceived by paediatric intensive care unit healthcare workers

A higher MDS-R moral distress score was

associated with the intention to quit. Healthcare

workers who intended to quit their jobs had

significantly higher moral distress scores (P<0.05).

A higher moral distress score was also associated

with higher DASS-21 depression factor (r=0.445;

P<0.05) and anxiety factor scores (r=0.417; P<0.05).

Nurses who had worked for a greater number of

years in the PICU also experienced higher moral

distress (r=0.512; P<0.05). Twenty-eight percent

of all participants and 35% of nurses reported they

intended to quit their jobs because of moral distress.

Psychological status

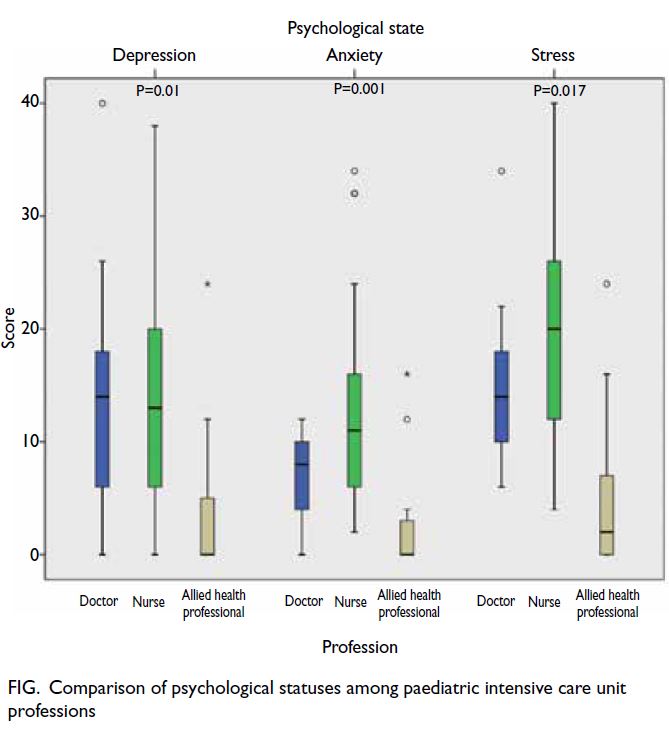

The median depression, anxiety, and stress scores

were 11 (IQR=0.5-18), 8 (IQR=3-145), and 30

(IQR=21-38), respectively; these scores corresponded

to mild depression, mild anxiety, and severe stress.

Among the three groups, nurses had the highest

median anxiety (11, IQR=6-16) and stress scores (20,

IQR=12-26) [Fig]; these scores corresponded to mild

depression, moderate anxiety, and moderate stress.

Participants with significantly higher depression

and anxiety (both P<0.05) scores also intended to

quit their jobs. There was no significant difference in stress score between participants who did and did

not intend to quit their jobs (P=0.434).

Discussion

Moral distress levels among various

healthcare workers

In this study, various levels of moral distress were

present in all three groups of PICU healthcare

workers. There was a significant difference in

MDS-R scores among the three professions, and

nurses had the highest median MDS-R score. This

finding is contrary to the results of previous PICU

studies, which showed that moral distress did

not differ among various healthcare workers.21 22

The literature suggests that nurses exhibit higher

moral distress scores because they often have less

autonomy concerning options in situations that

involve moral dilemmas, and they are required

to implement care plans with which they do not

agree.23 24 25 26 Studies of PICU healthcare workers’

behaviours in ethical and morally distressing

dilemmas have shown that 48% of PICU nurses

reported needing to perform actions that violated

their conscience. These results reflect the culture and

hierarchies of power in the PICU.23 26 27 Moreover,

nurses are the frontline workers who directly

experience the impacts of clinical decisions on

patients and their families.26 28 In newly established

PICUs, decreased self-confidence or increased fear

in a new working environment, combined with an

uncertain ethical climate, unclear team dynamics,

and less decision-making autonomy regarding

care plans, can cause nurses to perceive less moral

agency (ie, ability to act morally and change a

situation).22 24 25 26 29 30 31 A reduced sense of moral agency

can result in moral distress, which may be more

apparent in newly established PICUs.29 31

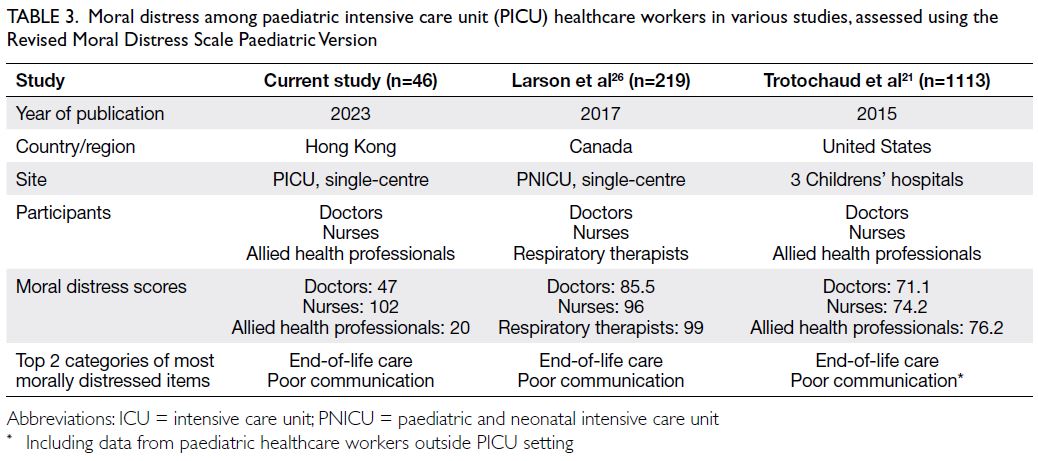

Our nurses’ moral distress levels among

published studies

We note that moral distress scores among nurses

in the present study are among the highest in

published studies of PICU healthcare workers (Table 3). In addition to the aforementioned lack of clarity in working environment and team dynamics, the

diverse levels of experience among nurses might

have also contributed to their high moral distress

scores. In the present study, 54% of nurses had <3

years of PICU experience, whereas 39% of nurses had

>10 years of PICU experience. These proportions of

nurses with extensive and minimal experience were

both larger than the proportions reported in previous

PICU studies.32 33 The presence of such a large

number of inexperienced junior nurses in the PICU

may place additional stress on more experienced

nurses. Indeed, survey items related to staffing (item

17 ‘Work with nurses or other care providers who

are less competent than the child’s care requires’ and

item 21 ‘Work with levels of care provider staffing

that I consider unsafe’ in the MDS-R) were ranked

by nurses as the seventh and eighth most morally

distressing items; these rankings were higher than in

other professions.

Table 3. Moral distress among paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) healthcare workers in various studies, assessed using the Revised Moral Distress Scale Paediatric Version

Case mix in contribution to moral distress

levels

The PICU case mix might also contribute to moral

distress. The majority of PICU admissions during

the study period involved patients with cancer,

who had considerably higher mortality rates; care

for such patients frequently involved end-of-life

and palliative care issues.34 35 In a study of nurses’

experiences while caring for dying children,

Davies et al36 found that when nurses recognise a

child’s death is inevitable, they often have to manage

conflicting obligations: follow the doctor’s treatment

orders and allow the child to die without unnecessary

pain. These disparate treatment goals for critically ill

children with terminal cancer can exacerbate moral

distress.36 37 In a comparison of moral distress scores

among various paediatric disciplines (eg, general

care and surgical service), Trotochaud et al21 found

that healthcare workers in haematology/oncology

areas experienced the second highest amount of

moral distress on the list, second to healthcare

workers in PICUs. Moreover, the proportion of

patients with cancer in our PICU is much higher

than the proportions in previous PICU studies.38 39

Therefore, it is entirely understandable that moral

distress in our PICU was particularly high among

nurses.

Years of experiences in paediatric intensive

care units in contribution to moral distress levels

The present study revealed a positive correlation

between years of PICU experience and moral

distress scores among nurses, consistent with

previous results concerning healthcare workers in

PICUs and adult ICUs.12 26 This correlation may be

related to effective utilisation of clinical knowledge

and experience, along with greater awareness concerning the impacts of potentially inappropriate

treatment plans on patients.40 Conversely, a study by

Larson et al26 revealed a negative correlation between

moral distress scores and years of experience among

doctors in the PICU. However, the present study

showed no correlation between moral distress scores

and years of experience among doctors. This finding

might be attributed to the small number of doctors

involved, which was insufficient to demonstrate an

association.

Potential impact of moral distress

Moral distress is often associated with the intention to

quit a job.41 42 43 44 The results of the study were consistent

with previous findings. Studies by Sannino et al11 and

Trotochaud et al21 showed that 10.3% to 25% of PICU

nurses intended to quit their jobs because of moral

distress. The proportion of nurses in our study who

intended to quit their job because of moral distress

(34.6%) was higher than the proportions in previous

PICU studies,11 21 which could be explained by their

high moral distress scores. However, further studies

are needed to determine the impact of moral distress

alone on a healthcare worker’s intention to quit their

job, compared with other possible distressing factors

(eg, working hours and promotional opportunities)

that can have a synergistic effect on the decision to

quit.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study of moral

distress among healthcare workers in an East Asian

PICU. The results of this study provide insights

concerning the broader understanding of moral

distress in newly established PICUs. The high

response rate also suggests strong participation and

indicates that the study sample is representative of

healthcare workers in our PICU.

However, the results of this study should be

interpreted with the following caveats. First, this

was a single-centre study with a relatively small

sample size, which limits the generalisability of the

findings. The small sample size also hindered further

evaluation of identifiable demographic factors, such

as education level and whether participants had any

children; another study indicated that such factors

may be associated with moral distress.11 Moreover,

the small sample size precluded subgroup analysis.

Second, this study was susceptible to ‘survivorship’

bias because the sample did not include PICU staff

who already quit their jobs, including some who

quit because of moral distress. Third, considering

the cross-sectional nature of this study, causal

relationships among various factors could not be

established. For example, although participants with

higher depression and anxiety scores reported a

stronger intention to quit their jobs, we could not

determine whether these participants reported more psychological symptoms because of their

intention to quit, or if their intention to quit led to

more psychological symptoms. Larger multicentre

studies are needed to further explore moral distress

among healthcare workers in Hong Kong PICUs.

As our unit expands to a 16-bed PICU and a five-bed

high-dependency unit, a longitudinal study will

also enhance the broader understanding of moral

distress dynamics in a developing PICU, as well as

the efficacies of various strategies to address moral

distress.

Coping strategies for moral distress and

stress

Considering the results of this study, moral distress

should be regarded as a key area for service

improvement. The high levels of moral distress

experienced by nurses, as well as the substantial

moral distress in relation to end-of-life care, suggest

that coping strategies should target nurses and focus

on end-of-life education. These coping strategies

are urgently needed to improve staff retention

and quality of care; they can be implemented at

the individual, organisational, and administrative

levels.20

At the individual level, ethics education is

essential for improvements in coping capacity and

sense of moral agency, which can reduce the levels

of moral distress.22 45 Education can be provided

through interactive workshops or self-guided

programmes.41 Prentice et al42 suggested that

education should focus on improving knowledge

regarding patient outcomes, the degree of uncertainty

in specific situations, and appropriate pain control.

Instead of emphasising ethical dilemmas and

underlying principles, education should highlight

communication skills, clarify values, and enhance

the overall understanding of the healthcare system

to address potential environmental conflicts.31 This

approach can ultimately increase staff confidence

(ie, moral courage) in constructively communicating

their concerns.42 Screening tools for various

emotional states, such as the DASS-21, should also

be included to help individuals gain better awareness

of their own psychological well-being and seek

professional help if necessary. Additionally, these

tools can be used to monitor emotions that might

cause moral distress.

At the organisational level, efforts should

be made to promote intra- and interdisciplinary

communication. Poor communication, one of the

five most morally distressing items, can lead to

diminished quality of care, reduced job satisfaction,

and poor patient outcomes.46 Ethics rounds, formal

and informal discussions, and debriefing sessions

regarding morally distressing cases could improve

interdisciplinary communication.22 These initiatives

can help promote better mutual understanding of viewpoints across disciplines and individuals.22

Participation in these events may also allow nurses

to feel more empowered and experience a greater

sense of decision-making autonomy.43 Finally, the

establishment of formal ethical consultation services

may provide support and clarification with respect

to ethical dilemmas.44

At the administrative level, administrators

should recognise that it is acceptable for staff to

perceive moral distress; this perception is a sign

of humanity and an affirmation of moral values.44

Improvements in clinical environments (eg,

reduction of staff shortages, promotion of intra- and

interdisciplinary collaboration, and encouragement

of a safe and supported ethical climate) can help

decrease moral distress.47 These measures include

providing respectful feedback to staff, empowering

staff to voice perceptions and emotions, and making

difficult decisions in a timely manner after open

discussion.48

Conclusion

This study revealed significant differences in moral

distress among doctors, nurses, and allied health

professionals in a newly established PICU in Hong

Kong. Nurses had the highest moral distress scores

among the three groups of PICU healthcare workers

in this study and among published studies involving

PICU nurses. Most areas of moral distress were

related to end-of-life care and poor communication.

Higher moral distress was also associated with

greater depression, anxiety, and intention to quit.

There is an urgent need for interventions to help

healthcare workers cope with moral distress and

create a more sustainable working environment.

Author contributions

Concept or design: WL Cheung, KL Hon, KKY Leung, WF Hui.

Acquisition of data: WL Cheung, KL Hon, KKY Leung, WF Hui.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: WL Cheung, KL Hon, KKY Leung, WF Hui.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Ref No.: HKCH-REC-2020-008) and was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference

on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guideline. All

participants provided informed consent to take part in the

research.

References

1. Jones S, Rantell K, Stevens K, et al. Outcome at 6 months

after admission for pediatric intensive care: a report of

a national study of pediatric intensive care units in the

United Kingdom. Pediatrics 2006;118:2101-8. Crossref

2. Cremer R, Leclerc F, Lacroix J, Ploin D; GFRUP/RMEF

Chronic Diseases in PICU Study Group. Children with

chronic conditions in pediatric intensive care units located

in predominantly French-speaking regions: prevalence and

implications on rehabilitation care need and utilization.

Crit Care Med 2009;37:1456-62. Crossref

3. Namachivayam P, Shann F, Shekerdemian L, et al. Three

decades of pediatric intensive care: who was admitted,

what happened in intensive care, and what happened

afterward. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11:549-55. Crossref

4. Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Chronic

conditions among children admitted to U.S. pediatric

intensive care units: their prevalence and impact on risk

for mortality and prolonged length of stay. Crit Care Med

2012;40:2196-203. Crossref

5. Ebrahim S, Singh S, Hutchison JS, et al. Adaptive behavior,

functional outcomes, and quality of life outcomes of

children requiring urgent ICU admission. Pediatr Crit

Care Med 2013;14:10-8. Crossref

6. Bruce CR, Miller SM, Zimmerman JL. A qualitative study

exploring moral distress in the ICU team: the importance

of unit functionality and intrateam dynamics. Crit Care

Med 2015;43:823-31. Crossref

7. Austin W. Moral distress and the contemporary plight of

health professionals. HEC Forum 2012;24:27-38. Crossref

8. Jameton A. Nursing practice: the ethical issues. Englewood

Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall Inc; 1984.

9. Garros D, Austin W, Carnevale FA. Moral distress in

pediatric intensive care. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:885-6. Crossref

10. Lusignani M, Giannì ML, Re LG, Buffon ML. Moral distress

among nurses in medical, surgical and intensive-care units.

J Nurs Manag 2017;25:477-85. Crossref

11. Sannino P, Giannì ML, Carini M, et al. Moral distress in the pediatric intensive care unit: an Italian study. Front Pediatr 2019;7:338. Crossref

12. Dodek PM, Wong H, Norena M, et al. Moral distress

in intensive care unit professionals is associated with

profession, age, and years of experience. J Crit Care

2016;31:178-82. Crossref

13. Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Guilleminault C, Caulet M. The

prevalence of depressive disorders in the United Kingdom.

Biol Psychiatry 1999;45:300-7.Crossref

14. de Vargas D, Dias AP. Depression prevalence in

intensive care unit nursing workers: a study at hospitals

in a northwestern city of São Paulo State. Rev Lat Am

Enfermagem 2011;19:1114-21. Crossref

15. Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse

burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:288-98. Crossref

16. Humphries N, Morgan K, Conry MC, McGowan Y,

Montgomery A, McGee H. Quality of care and health

professional burnout: narrative literature review. Int J

Health Care Qual Assur 2014;27:293-307. Crossref

17. Prompahakul C, Epstein EG. Moral distress experienced

by non-Western nurses: an integrative review. Nurs Ethics

2020;27:778-95. Crossref

18. Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and

testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in

healthcare professionals. AJOB Prim Res 2012;3:1-9. Crossref

19. Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of the Depression

Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument

for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based

cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry

2013;13:24. Crossref

20. Wang K, Shi HS, Geng FL, et al. Cross-cultural validation of

the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale–21 in China. Psychol

Assess 2016;28:e88-100. Crossref

21. Trotochaud K, Coleman JR, Krawiecki N, McCracken C.

Moral distress in pediatric healthcare providers. J Pediatr

Nurs 2015;30:908-14. Crossref

22. Sauerland J, Marotta K, Peinemann MA, Berndt A,

Robichaux C. Assessing and addressing moral distress and

ethical climate part II: neonatal and pediatric perspectives.

Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2015;34:33-46. Crossref

23. Papathanassoglou ED, Karanikola MN, Kalafati M,

Giannakopoulou M, Lemonidou C, Albarran JW.

Professional autonomy, collaboration with physicians, and

moral distress among European intensive care nurses. Am

J Crit Care 2012;21:e41-52. Crossref

24. Corley MC. Nurse moral distress: a proposed theory and

research agenda. Nurs Ethics 2002;9:636-50. Crossref

25. Wilkinson JM. Moral distress in nursing practice:

experience and effect. Nurs Forum 1988;23:16-29. Crossref

26. Larson CP, Dryden-Palmer KD, Gibbons C, Parshuram CS.

Moral distress in PICU and neonatal ICU practitioners:

a cross-sectional evaluation. Pediatr Crit Care Med

2017;18:e318-26. Crossref

27. Solomon MZ, Sellers DE, Heller KS, et al. New and

lingering controversies in pediatric end-of-life care.

Pediatrics 2005;116:872-83. Crossref

28. Molloy J, Evans M, Coughlin K. Moral distress in the

resuscitation of extremely premature infants. Nurs Ethics

2015;22:52-63. Crossref

29. McCarthy J, Gastmans C. Moral distress: a review of the

argument-based nursing ethics literature. Nurs Ethics

2015;22:131-52. Crossref

30. LaSala CA, Bjarnson D. Creating workplace environments

that support moral courage. Online J Issues Nurs

2010;15:Manuscript 4. Crossref

31. Epstein EG, Delgado S. Understanding and addressing

moral distress. Online J Issues Nurs 2010;15:Manuscript 1. Crossref

32. Ahmed GE, Abosamra OM. Knowledge of pediatric

critical care nurses regarding evidence based guidelines

for prevention of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). J

Educ Pract 2015;6:94-101.

33. Hickey PA, Pasquali SK, Gaynor JW, et al. Critical care

nursing’s impact on pediatric patient outcomes. Ann

Thorac Surg 2016;102:1375-80. Crossref

34. Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block

S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1133-8. Crossref

35. Wösten-van Asperen RM, van Gestel JP, van Grotel M,

et al. PICU mortality of children with cancer admitted to

pediatric intensive care unit a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2019;142:153-63. Crossref

36. Davies B, Clarke D, Connaughty S, et al. Caring for dying children: nurses’ experiences. Pediatr Nurs 1996;22:500-7.

37. Johnston EE, Alvarez E, Saynina O, Sanders L, Bhatia

S, Chamberlain LJ. Disparities in the intensity of

end-of-life care for children with cancer. Pediatrics

2017;140:e20170671. Crossref

38. Demaret P, Pettersen G, Hubert P, Teira P, Emeriaud G.

The critically-ill pediatric hemato-oncology patient:

epidemiology, management, and strategy of transfer to the

pediatric intensive care unit. Ann Intensive Care 2012;2:14. Crossref

39. Dalton HJ, Slonim AD, Pollack MM. Multicenter outcome

of pediatric oncology patients requiring intensive care.

Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2003;20:643-9. Crossref

40. Zhang W, Wu X, Zhan Y, Ci L, Sun C. Moral distress and its

influencing factors: a cross-sectional study in China. Nurs

Ethics 2018;25:470-80. Crossref

41. Beumer CM. Innovative solutions: the effect of a workshop

on reducing the experience of moral distress in an intensive

care unit setting. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2008;27:263-7. Crossref

42. Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, Davis PG. Moral distress

within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a

systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:701-8. Crossref

43. Browning AM. CNE article: moral distress and

psychological empowerment in critical care nurses caring

for adults at end of life. Am J Crit Care 2013;22:143-51. Crossref

44. Santos RP, Garros D, Carnevale F. Difficult decisions in

pediatric practice and moral distress in the intensive care

unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2018;30:226-32. Crossref

45. Burston AS, Tuckett AG. Moral distress in nursing:

contributing factors, outcomes and interventions. Nurs

Ethics 2013;20:312-24. Crossref

46. Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, Epstein EG,

Fisher JM. Moral distress among healthcare professionals:

report of an institution-wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh

2015;47:117-25. Crossref

47. Atabay G, Çangarli BG, Penbek Ş. Impact of ethical climate

on moral distress revisited: multidimensional view. Nurs

Ethics 2015;22:103-16. Crossref

48. Benoit DD, Jensen HI, Malmgren J, et al. Outcome in

patients perceived as receiving excessive care across

different ethical climates: a prospective study in 68

intensive care units in Europe and the USA. Intensive Care

Med 2018;44:1039-49. Crossref