© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Promoting integrated healthcare for Hong Kong

and Macau residents in the Greater Bay Area during the COVID-19 pandemic

Pearl MC Pai, MD, FRCP1,2; Joe KM Fan, MS (HKU), FRCSEd2,3; William CW Wong, MD, FRCP2,4; XF Deng, MBA5; XP Xu, MD5; CM Lo, MS (HKU), FRCSEd2,3

1 Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

2 School of Clinical Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

4 Department of Family Medicine, The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

5 Clinical Service, The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

Corresponding author: Dr Pearl MC Pai (ppai1@hku.hk)

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

has affected the world health system drastically,

almost rendering it beyond recognition. At the

height of the pandemic, many patients were unable

to access the healthcare they desperately needed

because hospitals were overwhelmed and exhausted.

Hospitals in many places have been pushed to

the edge of collapse, unable to admit patients for

essential care or provide outpatient services as part

of ongoing chronic disease management.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in

mainland China, many permanent residents of Hong

Kong living in Guangdong Province were unable to

return home for their clinic appointments under

the Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA) due to

quarantine and travel restrictions between Hong

Kong and mainland China. In 2020, the Government

of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

(HKSAR), the Shenzhen Municipal Government,

and The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen

Hospital (HKU-SZH) agreed to initiate and operate

a HA special support scheme under which such

patients could use the clinical services available at

HKU-SZH to meet their needs.

Brief overview of The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital and its mission

Hong Kong and Shenzhen are separated by the

Shenzhen River and are some 35 kilometres apart.

The HKU-SZH is a joint project between HKU and the

Shenzhen Municipal Government and was formed

in 2011 as part of the Chinese health reform.1 In less

than a decade, it has been awarded Australian Council

on Healthcare Standards accreditation and was

granted the status of a ‘Grade 3A’ hospital (the highest

ranking given by the national hospital accreditation

system of mainland China) as well as several other

prestigious awards. In the 2020 Development Report

on Health Reform in China,2 HKU-SZH has been noted as having been instrumental in the Chinese

health reform. In fact, this is one of the missions that

the Hospital was designed and built. Many innovative

service models have been introduced, including the

primary-secondary care interface and the package

fee for family medicine consultation; these have

subsequently drawn much attention from other

hospitals. Above all, it was expected to integrate the

best Western model of healthcare delivery with the

best Chinese model, thereby providing a socialistic

approach to medicine with Chinese characteristics.

The Hospital has been working hard on this and

making progress.

Use of Elderly Health Care Vouchers in The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital

In 2009, the Hong Kong SAR Government established

the Elderly Health Care Voucher (EHCV) Scheme to

support its elderly residents. Those who are eligible

currently receive HK$2000 (equivalent to US$250)

per year. Since October 2015, to increase utilisation

of the Scheme, the Hong Kong SAR Government has

allowed eligible elderly patients to pay for treatment

at HKU-SZH with their EHCVs. Since its launch,

HKU-SZH has recorded over 45 000 EHCV patient

episodes or outpatient attendances. In the process,

the Hospital has established a payment mechanism

with the HA for reimbursement, which will likely be

useful in the future for similar schemes. The Scheme

is in line with the Central Government’s policy

of enabling hospitals with similar backgrounds to

provide quality healthcare for residents of Hong

Kong living in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA).3

Hong Kong SAR Government’s special support scheme and its implementation

In 2020, the Hong Kong SAR Government estimated that between 18 000 to 38 000 Hong Kong residents

living in Guangdong Province were attending

HA clinics in Hong Kong for chronic disease

management.4 Because of the travel restrictions

during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of them were

unable to return to Hong Kong and had to depend

on postal delivery of their repeat prescriptions. In

late 2020, the HKSAR Government decided to set up

the HKSAR Government Special Support Scheme

for Hospital Authority Chronic Disease Patients

Living in the Guangdong Province to Sustain Their

Medical Consultation under COVID-19 (the Support

Scheme). Under the Support Scheme, patients who

had HA appointments between 17 February 2020

and 31 July 2021 and were unable to return to Hong

Kong for their HA appointments because of the

pandemic-related travel restrictions were allowed

to use the following HA outpatient services at

HKU-SZH: family medicine, medical and surgical

specialties, ophthalmology, gynaecology, oncology,

orthopaedics, paediatrics, and the pain clinics. Each

patient received 2000 yuan per year (equivalent to

US$300) which could be used to pay for outpatient

investigations and medications at designated clinics

at HKU-SZH providing clinical services offered by

the HA to carry out the Support Scheme. The expiry

date of the scheme was later extended to May 2023.

Because the HA and HKU-SZH had been

working well together under the EHCV Scheme,

HKU-SZH was invited to run the new Support

Scheme. To set up the special HKU-SZH–HA clinics,

HKU-SZH developed a smartphone application

with which patients could request an appointment.

When doing so, patients will be asked to upload their

HA appointment slips and to authorise HKU-SZH

to apply for their electronic health records and

access their personal health details from the HA.

The application is then checked at the HKU-SZH

appointment booking centre before being forwarded

to the HA electronically as encrypted data. Once the

application is processed by the HA, encrypted copies

of the patient’s eHealth file will be transmitted to

HKU-SZH where a clinic appointment is generated.

All these actions are done with the consent of the

patients and the secure storage and transmission of

the data is supported and protected by information

technology infrastructure, cybersecurity and data

security laws, and, more recently, by the Personal

Information Protection Law of China. The patients

must pay a consultation fee of 100 yuan (equivalent

to US$15), similar to mainland residents, as well as

any excess charges.

Additionally, a special telephone line and

walk-in enquiry desk with Cantonese-speaking

staff have been set up. There is also clear signage

at the outpatient reception, payment counter, and

medication collection window. The logo was designed using the HA pantone colour, which is familiar

to patients from Hong Kong. Each department at

the Hospital has selected its most suitable doctors

in terms of languages and experience to staff the

clinics. It should be noted that many of the Hospital’s

doctors have been taught and trained in mainland

China and therefore have limited English ability.

Prior to the opening of HKU-SZH–HA clinics in

November 2020, several orientation sessions were

held, including a briefing session in which the then–Hospital Chief Executive Professor Chung-mau Lo

delivered an encouraging speech. He emphasised the

importance of the Support Scheme and explained

to the doctors the usual HA clinic process and

behaviours and expectations of its patients. The

doctors were reminded of the brief nature of many

HA clinic letters, their frequent use of abbreviations,

and the use of English medication names, and that

they might need some time to become familiar with

all these.

Analysis of implementation of

The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital-Hospital

Authority clinics: a step towards

connection and integration

The HKU-SZH conducted a performance analysis

of its HKU-SZH–HA clinics in March 2021, some

5 months after their opening. A total of 11 000

enquires and 10 938 patient episodes or clinic

attendances had been recorded in the Hospital

under the Support Scheme. The mean age of the

patients was 65.5 ± 13.5 years (range, 1-103). The

male-to-female ratio was 2.13:1. From 1 January to

31 December 2021, there were 28 386 attendances

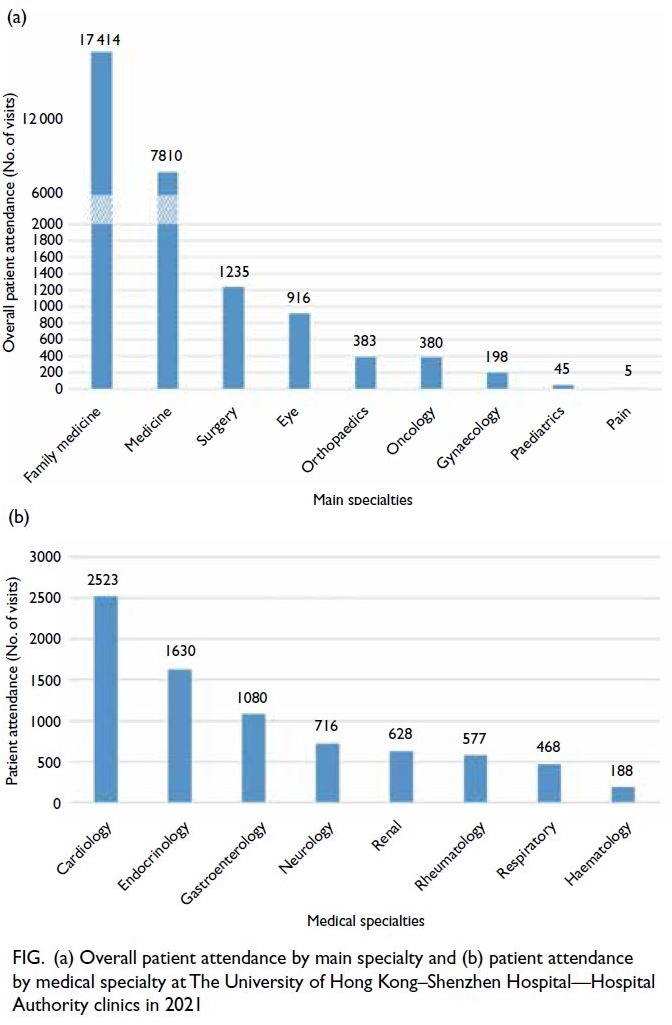

or patient episodes (Fig a). The most utilised clinics

were the chronic disease clinic (17 414 attendances)

served by the family medicine physicians, followed

by the medical specialty clinics (7810 attendances).

Figure b shows the patient distribution among the

eight medical specialties; there was good cooperation

between the family medicine doctors and specialty

doctors for onward referral, which helped to drive up

the utilisation of these clinics. The 10 most common

conditions for which patients received treatment

were hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery

disease, ischaemic heart disease, dyslipidaemia,

aftercare of post-coronary artery stent, gout, atrial

fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Feedback from

doctors and patients of HKU-SZH–HA clinics was

mostly positive. Although the scope of the Support

Scheme was rather limited, it was extraordinarily

significant. It demonstrated that, despite assorted

difficulties, integrated medical care is working and

sustaining.

Figure. (a) Overall patient attendance by main specialty and (b) patient attendance by medical specialty at The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital—Hospital Authority clinics in 2021

Experiences shared and humble wishes

The HA has been providing quality yet affordable,

and almost free, healthcare services to its patients

in Hong Kong. As the GBA becomes increasingly

popular as a place for work, living, and retirement

for Hong Kong residents, how could the HA health

service follow, serve, and protect them when they

venture into the GBA and beyond? Their decision

whether to relocate to a new residing place in the

GBA or not would be very much influenced by the

availability and affordability of healthcare there. The

successful management of the EHCV Scheme and

the Support Scheme by HKU-SZH indicates possible

directions for the future, but the additional funding

or support required for implementation of similar schemes might be very costly and warrant serious consideration.

If we were to improve the integrated healthcare

delivery at HKU-SZH, the highest priorities would

be to streamline the application process for patients,

speed up the transmission of patient records between

healthcare providers in Hong Kong and Shenzhen,

and enable mutual recognition of laboratory and

radiology reports to avoid duplicated tests and waste.

Government plans to connect and

integrate medical services in the Greater Bay Area

In October 2020, the General Office of the Chinese

State Council proclaimed a directive entitled

‘Implementation Plans on Building Shenzhen into a

Pilot Demonstration Zone of Socialism with Chinese

Characteristics’.3 The title is clear enough to convey

to the nation what the Central Government wants

from and for the nation itself and its people—a

model of a modern metropolis within a strong

nation under socialism with Chinese characteristics,

of which a world-leading health service is an

indispensable component. Answering its call, the

Shenzhen Municipal Government released its own

guideline and the ‘Implementation Plan for the

Pilot Comprehensive Reform of Building a Pilot

Demonstration Zone of Socialism with Chinese

Characteristics in Shenzhen’ (the ‘Pilot Reforms

Plan’) to coincide with its 40th anniversary as a

Special Economic Zone. Among the most important

purposes of the ‘Pilot Reforms Plan’ is to increase

cross-border connection and integration of medical

services between Hong Kong and Shenzhen, as well

as any other borders in the GBA.5 In short, this is

another ‘open for reform’ following the one launched

in 1978. In its 11 measures, it asks both sides of the

border to relieve the congestion of healthcare in

the GBA; promote better circulation of healthcare

resources; allow Shenzhen residents to access

good and qualified Hong Kong doctors; enable the

use of advanced medications from Hong Kong;

allow Hong Kong and Macau residents to receive

good healthcare in mainland China; simplify the

transfer of patients across the border; speed up the

evaluation process and approval of health projects;

and publicise the successful work of HKU-SZH

under the special Support Scheme and the EHCV

scheme and its successful payment mechanism.

Hopefully as a result, other approved hospitals in

Shenzhen may join the integrated medical services

and utilise the payment mechanism to provide good

and reliable services to Hong Kong residents and

their families living in Shenzhen and GBA in the

future. Together, the Directive and the Pilot Reforms

Plan have covered cross-border connection and

integration in every sector of healthcare, extending

from teaching, training, and practice of healthcare workers to medications and hospital management.

Here, in the 11 measures mandated, as the challenges

for connection and integration have been itemised,

something can be done to meet them.

Connection and integration achieved

Following the proclamation of the Directive and

the Pilot Reforms Plan, and under pressure from

the pandemic, the following practical actions

have taken place. In August 2021, Shenzhen had

accredited and granted 37 senior doctors working in

HKU-SZH and from Hong Kong the Chinese title of

chief physician.6 It marked the first time Shenzhen

had awarded this senior professional title to Hong

Kong doctors working in the city. Similarly, the HKU

School of Clinical Medicine has awarded honorary

titles, such as associate professorships, to doctors

from mainland China working in HKU-SZH. These

actions have demonstrated some mutual recognition

of medical qualifications and competencies.

Additionally, the Shenzhen Health Commission

has granted limited medical registration to several

doctors from Hong Kong and Macau allowing them

to practise locally. The implementation of the ‘Hong

Kong and Macau Medicines and Devices policy’7 in

November 2021 has been another effort to provide

integrated healthcare for Hong Kong and Macau

residents living in the GBA. Up to May 2023, under

the special permit, 20 drugs and 11 medical devices

and reagents have been approved and imported by

HKU-SZH for use. It has shared its experience with

four other pilot hospitals in the GBA. It has also been

asked to develop a standard operating procedure for

cross-border connections related to the import of

drugs and medical devices which has been proven

useful to healthcare workers on both sides.

Medical training of international standard is

also taking shape in Shenzhen. Hundreds of HKU

medical students used to attend clinical attachment

in HKU-SZH until it was disrupted by the pandemic.

To speed up the integration of medical training, in

September 2021, the Shenzhen Health Commission

had approved the development of a pilot specialist

training programme by HKU-SZH through the

Shenzhen–Hong Kong Medical Specialist Training

Centre8 and with the full support of the Hong Kong

Academy of Medicine, the respective specialty

Colleges of Hong Kong, and the Shenzhen Medical

Doctors Association. A new medical school of The

Chinese University of Hong Kong is also under

construction in Shenzhen.9

The cross-border connection and integration are

progressing rapidly in multiple directions and levels.

All the measures discussed here, as well as several

others, are important and effective in accelerating the

pace of cross-border connection and the integration of medical services in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Macau,

the GBA, and beyond. All signs have shown that

not only the connection and integration of medical

services are working, but they will also be sustained

and sustainable in the long run. The connection and

integration programme has yielded good results and

been proven successful and rewarding.

Challenges and sustainability

There are many challenges in the connection

and integration programme, including language

barriers, varying medical training and backgrounds,

differences in culture and governance, and shortage

of human resources and funding. So far, these have

been confronted and resolved successfully. The large

number of episodes of connection and integration

discussed above suggests that connection and

integration in healthcare have been succeeding,

sustained, and striding on within a rather short

period of time. The COVID-19 pandemic provided

a bitter lesson to the Central Government and its

people that a pandemic can harm and destroy a

government, regime, metropolis, nation, and people.

There is no better defence than good healthcare, and

the most expedient and least expensive way to possess

it is through continuing and sustainable connection

and integration with world class healthcare systems.

Although this is a difficult task, it is achievable,

especially so in GBA with its abundant resources.

Promotion of connection and

integration under the fifth wave of COVID-2019 in Hong Kong

The fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong

accelerated the pace of forming healthcare

connections and partnerships between Hong

Kong and mainland China. The mainland Chinese

healthcare workers started to arrive in Hong Kong

in the middle of March 2022 when the fifth wave of

COVID-19 began. A total of 391 medical workers,

mainly from Guangdong Province, arrived at the

community treatment facility at AsiaWorld-Expo.10

Within a week, they had learned on the job the Hong

Kong nursing standard operating procedure and

information technology structure and were working

side by side with their HA workmates. Meanwhile,

at Lok Ma Chau, some 20 000 mainland Chinese

workers finished building a massive makeshift

hospital within weeks.11 The mainland Chinese

healthcare workers went and served wherever and

whenever they were needed. Their knowledge, skill,

enthusiasm, good manner, and ethics impressed

the patients, their Hong Kong colleagues, and the

public. As the fifth wave of COVID-19 faded in Hong

Kong and the Chinese healthcare workers were

packing to return home, there were many favourable reports at all levels regarding the support provided

by them and the Central Government.10 The positive

experiences and encounters of medical workers on

both sides during the COVID-19 pandemic have

led to the belief that mutual learning, concern,

assistance, and cooperation, between the two

different medical systems are achievable and will be

helpful in providing quality healthcare in the GBA

and beyond. These experiences undoubtedly serve as

one of the best ways to promote the programme of

connection and integration.

Summary

Both the Central and the Hong Kong SAR

Governments are determined to build a healthy

nation and city. Just as the fifth wave of COVID-19

stabilised, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive–elect Mr

John Lee pledged on 29 April 2022, to develop a

better health service and caring society for Hong

Kong in his policy manifesto.12 Meanwhile the Central and Shenzhen Governments have continued

to engage in building Shenzhen into a model

and modern metropolis in a strong nation under

socialism with Chinese characteristics to be followed

by future Chinese cities. Hong Kong, Shenzhen,

and Macau, the ‘Tri-Cities’, are asked to enhance

their participation in and contribution to the grand

development of the GBA. The GBA is expanding

and flourishing. Using well of the talent, wisdom,

intelligence, experience, and resources of their cities

and their residents, Hong Kong will continue to

show its caring character, and Shenzhen will develop

itself into an ultra-modern metropolis in a strong

nation under socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PMC Pai, JKM Fan, WCW Wong, XP Xu, CM Lo.

Acquisition of data: XF Deng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PMC Pai, JKM Fan, WCW Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: PMC Pai.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: XF Deng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PMC Pai, JKM Fan, WCW Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: PMC Pai.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Prof Anne Wing-mui Lee and Dr Joseph Chi-yuen Chan from The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital

(HKU-SZH) for their direct contribution to the Hospital

Authority clinic service in HKU-SZH, and Prof Walter Wai-kay Seto from Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine of The University of Hong Kong for his advice to the manuscript.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of The University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital has waived the need for ethics

approval and patient consent for this study.

References

1. Chu P, Pai P. A new great wall: commissioning a new hospital in China. Future Hosp J 2015;2:28-33. Crossref

2. Liang W, Wang C, Wu P, editors. Blue Book of Health Reform. Development Report on Health Reform in China

2020. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press; 2020.

3. Ministry of Commerce of The People’s Republic of China. Implementation Plan (2020-2025) Issued by the General

Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General

Office of the State Council for Comprehensive Pilot Reform

in Shenzhen to Build the City into a Pilot Demonstration

Zone for Socialism with Chinese Characteristics [in

Chinese]. Available from: http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/resume/n/202010/20201003006969. Accessed 31 Mar 2022.

4. 政府擬託港大深圳醫院為港人診症. News.gov.hk. Available from: https://www.news.gov.hk/chi/2020/09/20200915/20200915_171027_139.html. Accessed 12 Jun 2023.

5. 深圳市人民政府辦公廳.《關於加快推動醫療服務跨

境銜接的若干措施》. Available from: http://www.sz.gov.cn/attachment/0/774/774421/8724838.pdf Accessed 31 Mar 2022.

6. Zhang Y. City bestows senior title to 37 HK medical professionals. Shenzhen Daily. 6 August 2021. Available

from: http://www.szdaily.com/content/2021-08/06/content_24459894.htm. Accessed 31 Mar 2022.

7. 廣東省藥品監督管理局. 省藥品監管局切實推進“港澳藥械通”政策 提升灣區居民幸福感. Available from: http://mpa.gd.gov.cn/xwdt/sjdt/content/post_3500048.html. Accessed 25 May 2022.

8. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. SZ-HK Medical Specialist Training Centre. Available from: https://www.hkam.org.hk/en/initiative/sz-hk-medical-specialist-training-centre. Accessed 23 May 2022.

9. CUHK-SZ unveils new medical school. Shenzhen Daily. 18 August 2021. Available from: https://www.cnbayarea.org.cn/english/News/content/mpost_538179.html. Accessed 11 May 2022.

10. Li Y. HKSAR Chief Executive sees off mainland medical workers supporting pandemic fight. Chinanews.com. 6 May 2022. Available from: http://www.ecns.cn/news/2022-05-06/detail-ihayamfc5315102.shtml. Accessed 5 Jun 2022.

11. Chan O. First phase of emergency hospital handed over to Hong Kong. Chinadaily.com.cn. 18 April 2022. Available from: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202204/08/WS624f71bba310fd2b29e55ac6.html Accessed 5 Jun 2022.

12. CE-elect pledges new era of unity. News.gov.hk. Available from: https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2022/05/20220508/20220508_140909_199.html. Accessed 5 Jun 2022.