Hong Kong Med J 2023 Feb;29(1):11-4 | Epub 8 Feb 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

The role of a single-shot higher-valency pneumococcal vaccine in overcoming challenges regarding invasive pneumococcal disease in Hong Kong

Christopher KM Hui, MB, BS, FRCP1; Ivan FN Hung, MD, PDiPID2,3; Bing Lam, MB, BS, PDipID4; Ada WC Lin , MB, BS, PDipID5; Thomas MK So, MB, BS, FRCP6; Andrew TY Wong, MB, BS, MPH7;

Martin CS Wong, MD, MPH8,9

1 813 Medical Centre, Hong Kong

2 Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Gleneagles Hospital Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

5 HKSH Medical Group, Hong Kong

6 Virtus Medical Centre, Hong Kong

7 Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

8 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

9 Editor-in-Chief, Hong Kong Medical Journal

Corresponding author: Dr Christopher KM Hui (christopher.hui@uclmail.net)

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), a major

public health problem worldwide (including in

Hong Kong),1 2 3 is a severe and potentially life-threatening

infectious disease caused by the gram-positive

bacterium, Streptococcus pneumoniae.1 2

The clinical manifestations of acute IPD vary among

organ systems involved; they include severe and

potentially fatal infections such as community-acquired

pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis.2 In

Hong Kong, pneumonia has consistently been

the second leading cause of death since 20124; it

is associated with higher rates of hospitalisation

and higher healthcare costs, particularly among

older adults.5 6 Despite appropriate treatment,

up to 50% of IPD survivors experience long-term

complications, including respiratory, cardiovascular,

and neurological sequelae.7 Invasive pneumococcal

disease is associated with substantial healthcare

and economic burdens; thus, it represents an acute

public health problem in Hong Kong, particularly

amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

pandemic. There is an urgent need to develop

effective strategies that can mitigate the potential

threat of an IPD outbreak.

Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in

Hong Kong

Invasive pneumococcal disease has been a statutorily

notifiable disease in Hong Kong since January 2015.8

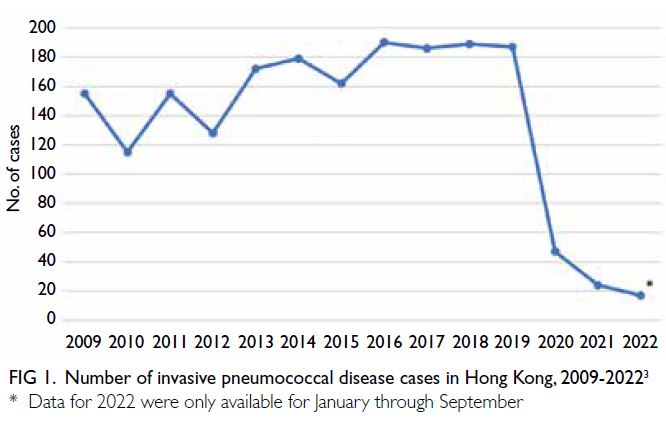

Between 2015 and 2019, the Centre for Health

Protection recorded a median of 187 (range: 162-190) IPD cases per year; the emergence of COVID-19 in 2020 led to a dramatic decrease in the number

of IPD cases in Hong Kong (Fig 1).3 However, the

current IPD burden is severely underestimated because of underdiagnosis, and a high index of

suspicion for IPD is a central aspect of differential

diagnosis. Because the clinical symptoms of IPD

overlap with the symptoms of other respiratory

illnesses, inexperienced physicians may experience

challenges regarding specimen collection (ie, samples

may be inappropriately or inadequately collected);

such challenges contribute to the underutilisation of

diagnostic tests and underreporting of IPD.

Because S pneumoniae is transmitted by direct

contact with respiratory secretions from patients

with IPD and from healthy carriers,2 9 public health

measures (eg, mask wearing, social distancing, travel

restrictions, and quarantine) that were implemented

to prevent the transmission of severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 also reduced

the spread of S pneumoniae; thus, the number of

IPD cases has decreased since the beginning of 2020

(Fig 1).3 As Hong Kong emerges from the COVID-19

pandemic, the gradual relaxation of public health

intervention measures is expected to result in

an increased number of IPD cases. Moreover,

seasonality could contribute to a sudden increase

in IPD cases because respiratory diseases (eg,

pneumococcal infection and influenza) are generally

more prevalent during winter and early spring.10 11

Notably, Israel experienced a nationwide outbreak

of S pneumoniae serotype 2 between 2015 and 2019,

despite the availability of vaccination programmes.12

Such outbreaks highlight the need to formulate

effective strategies for early disease prevention.

Pneumococcal vaccination in Hong Kong

Two types of pneumococcal vaccines are available to prevent IPD: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPSVs) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines

(PCVs). The 23-valent PPSV (PPSV23) contains

purified capsular polysaccharide antigens from 23

distinct S pneumoniae serotypes, whereas PCVs—including PCV13, PCV15, and PCV20—contain

purified capsular polysaccharide antigens from 13,

15 or 20 serotypes of S pneumoniae conjugated to

a nontoxic variant of diphtheria toxin (CRM197),

along with aluminium phosphate as an adjuvant.13 14

In contrast to PPSVs, the conjugated complexes

contained in PCVs exert long-term protection

because they are able to stimulate T-cell-dependent

immune response to generate immune memory for

the specific S pneumoniae serotypes covered by

the vaccine.15 Importantly, clinical trials and real-world

evidence have consistently demonstrated

the effectiveness of PCV13 in providing serotype-specific

protection against IPD.2 13 16 Although IPD

can occur at any age, an increased risk of onset

is associated with various factors; mortality is

substantially higher in children <2 years and adults

aged ≥65 years.10 13 In Hong Kong, the current

recommendations for pneumococcal vaccination

by the Centre for Health Protection prioritise adults

aged ≥65 years with high-risk conditions,17 consistent

with recommendations from the United States

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.18

Specifically, pneumococcal vaccine-naïve individuals

with high-risk conditions are recommended to

receive one dose of PCV13, followed by one dose of

PPSV23 at 1 year after PCV13 vaccination.17

Since 2017, the Hong Kong government

has provided free or subsidised pneumococcal

vaccination to eligible individuals through the

Government Vaccination Programme (GVP) and the

Vaccination Subsidy Scheme (VSS).19 Despite this

governmental support, rates of vaccine uptake and

participation in GVP and VSS remain low.19 Concerns

regarding vaccine efficacy, poor understanding of the disease, and lack of clarity regarding vaccine

schedules are some of the major challenges that

limit pneumococcal vaccination among adults in

Hong Kong.19 Another limiting factor is vaccine

hesitancy related to perceived vaccination burden

and fatigue.20

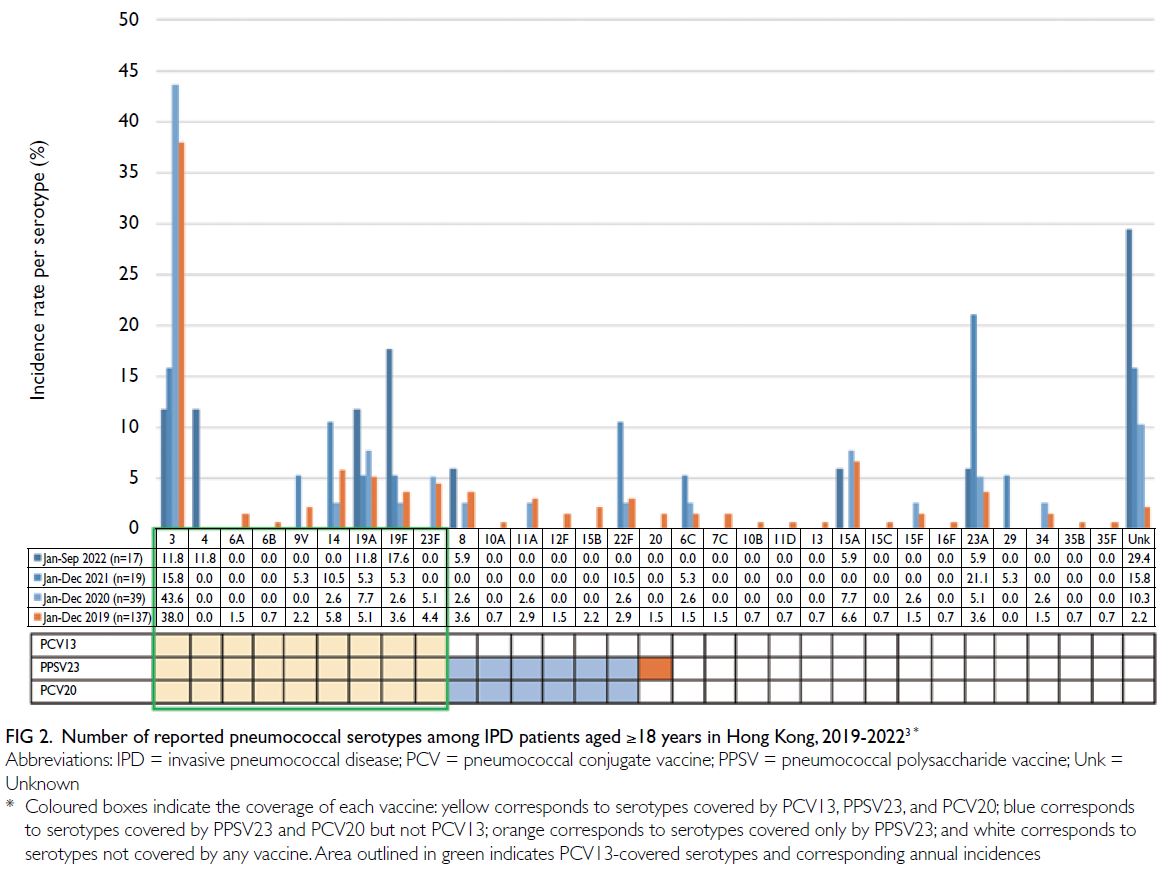

Current serotype burden in Hong Kong

Data from continuous surveillance of pneumococcal

serotypes have facilitated analyses of serotypes

isolated from the community, which have yielded

insights regarding the effectiveness and limitations

of pneumococcal vaccination programmes. Since

the implementation of pneumococcal vaccination in

Hong Kong, the incidence of IPD involving vaccine-covered

serotypes has considerably decreased.

However, because of low vaccination rates in

recent years, PCV13-covered serotypes (including

serotypes 3, 19F, and 19A) have been identified

in half of all reported IPD cases (Fig 2).3 21 22 23

Importantly, although it is covered by PCV13

and PPSV23, serotype 3 remains a major cause

of IPD because its unique polysaccharide capsule

resists detection by vaccine-induced antibodies.24

Moreover, the emergence of non-vaccine serotypes

(Fig 2; ie, serotype replacement) also poses a public

health threat.23 25

Figure 2. Number of reported pneumococcal serotypes among IPD patients aged ≥18 years in Hong Kong, 2019-20223

A higher-valency vaccine for broader

protection against invasive pneumococcal disease

Considering the current challenges in Hong Kong, a

higher-valency PCV (eg, PCV20) could partly address

the potential public health problem associated with

serotypes that are not covered by the Hong Kong

vaccination programme. The 20-valent PCV provides broader

protection against IPD; a single dose contains seven

new serotypes, in addition to the serotypes covered

by PCV13.26 Phase 3 studies of clinical efficacy

have demonstrated that PCV20 is noninferior to

PCV13 and PPSV23 across a subset of age-groups,

regardless of pneumococcal vaccination history and

high-risk conditions.27 28 Importantly, PCV20 can

be concurrently administered with influenza and

COVID-19 vaccines.26

In October 2021, the Advisory Committee on

Immunization Practices recommended one dose

of PCV20 alone, or serial immunisation (PCV15,

followed by PPSV23), for all PCV/PPSV-naïve

adults aged ≥65 years and PCV/PPSV-naïve adults

aged 19-64 years with high-risk conditions.26 The

implementation of a PCV20 single-shot vaccination

programme could be a cost-effective strategy

to address the current burden of IPD cases that

involve serotypes covered by PCV13 and serotypes

unique to PCV20.29 Furthermore, the convenience

of a simplified vaccination schedule could improve

vaccine uptake.

Overcoming challenges in Hong Kong and

implementing preventive strategies against invasive pneumococcal disease

The government and physicians play key roles

in promoting pneumococcal vaccination and

improving vaccine uptake, particularly among older

adults. Because the perceived low burden of IPD

may reduce the rate at which physicians recommend

vaccination for their patients,30 there is a need to

improve physician awareness regarding IPD and the

benefits of pneumococcal vaccines for individuals

with an increased risk of IPD.

Continuing medical education programmes

for physicians could cover periodic updates

regarding the IPD burden in Hong Kong, current

pneumococcal vaccine schedules, proper sample

collection methods, and appropriate diagnostic

tests for confirmation of IPD in patients with

relevant symptoms. These initiatives can improve

early diagnosis and treatment of IPD, facilitate

accurate data collection regarding IPD incidence,

and help to manage the underestimated burden of IPD. Additionally, government-led public education

campaigns that focus on bridging knowledge gaps

with respect to (i) the public health impact of IPD

(a vaccine-preventable disease), and (ii) vaccine

accessibility through GVP and VSS, could help to

overcome vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccine

uptake in Hong Kong.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Funding/support

Funding for this study was provided by Pfizer

Hong Kong. Editorial and medical writing support

was provided by Dr Analyn Lizaso from Weber

Shandwick Hong Kong, funded by Pfizer Hong Kong.

References

1. Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. Burden of

Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae

type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines:

global, regional, and national estimates for 2000-15. Lancet

Glob Health 2018;6:e744-e757. Crossref

2. Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. Streptococcus

pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat

Rev Microbiol 2018;16:355-67. Crossref

3. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Report on IPD. Available

from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/resources/29/636.html. Accessed 6 Aug 2022.

4. Centre for Health Protection. Death rates by leading causes of death, 2001-2021. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/27/117.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

5. Li X, Blais JE, Wong IC, et al. Population-based estimates of

the burden of pneumonia hospitalizations in Hong Kong,

2011-2015. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;38:553-61. Crossref

6. Man MY, Shum HP, Yu JS, Wu A, Yan WW. Burden of

pneumococcal disease: 8-year retrospective analysis

from a single centre in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:372-81. Crossref

7. Brooks LR, Mias GI. Streptococcus pneumoniae’s virulence

and host immunity: aging, diagnostics, and prevention.

Front Immunol 2018;9:1366. Crossref

8. Hong Kong e-Legislation. Cap. 599 Prevention and Control

of Disease Ordinance. Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap599" target="_blank. Accessed Sep 2022.

9. Chan KP, Ma TF, Ip MS, Ho PL. Invasive pneumococcal

disease, pneumococcal pneumonia and all-cause

pneumonia in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic

compared with the preceding 5 years: a retrospective

observational study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e055575. Crossref

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology

and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 14th

edition. 2021. Available from: https://www.merle-arbeitsmedizin.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/CDC-Pink-Book-Version-14th-Edition.pdf. Accessed Nov 2022.

11. McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol ev

2006;19:571-82. Crossref

12. Dagan R, Ben-Shimol S, Benisty R, et al. A nationwide

outbreak of invasive pneumococcal disease in Israel caused

by Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 2. Clin Infect Dis

2021;73:e3768-77. Crossref

13. Bridy-Pappas AE, Margolis MB, Center KJ, Isaacman DJ.

Streptococcus pneumoniae: description of the pathogen,

disease epidemiology, treatment, and prevention.

Pharmacotherapy 2005;25:1193-212. Crossref

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About pneumococcal vaccines. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/about-vaccine.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

15. Berger A. Science commentary: why conjugate vaccines protect longer. BMJ 1998;316:1571. Crossref

16. Theilacker C, Fletcher MA, Jodar L, Gessner BD. PCV13

vaccination of adults against pneumococcal disease:

what we have learned from the Community-Acquired

Pneumonia Immunization Trial in Adults (CAPiTA).

Microorganisms 2022;10:127. Crossref

17. Centre for Health Protection Scientific Committee on

Vaccine Preventable Diseases. Updated recommendations on the use of pneumococcal vaccines for high-risk

individuals. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/updated_recommendations_on_the_use_of_pneumococcal_vaccines_for_high-risk_individuals.pdf.

Accessed 6 Oct 2022.

18. Morga A, Kimura T, Feng Q, Rozario N, Schwartz J. Compliance to Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices recommendations for pneumococcal vaccination.

Vaccine 2022;40:2274-81. Crossref

19. Huang J, Mak FY, Wong YY, et al. Enabling factors, barriers,

and perceptions of pneumococcal vaccination strategy

implementation: a qualitative study. Vaccines (Basel)

2022;10:1164. Crossref

20. Su Z, Cheshmehzangi A, McDonnell D, da Veiga CP, Xiang YT. Mind the “Vaccine Fatigue”. Front Immunol

2022;13:839433. Crossref

21. Ho PL, Law PY, Chiu SS. Increase in incidence of invasive

pneumococcal disease caused by serotype 3 in children

eight years after the introduction of the pneumococcal

conjugate vaccine in Hong Kong. Hum Vaccin Immunother

2019;15:455-8. Crossref

22. Subramanian R, Liyanapathirana V, Barua N, et al.

Persistence of pneumococcal serotype 3 in adult

pneumococcal disease in Hong Kong. Vaccines (Basel)

2021;9:756. Crossref

23. Hon KL, Chan KH, Ko PL, et al. Change in pneumococcus

serotypes but not mortality or morbidity in pre- and

post-13-valent polysaccharide conjugate vaccine era:

epidemiology in a pediatric intensive care unit over 10

years. J Trop Pediatr 2018;64:403-8. Crossref

24. Luck JN, Tettelin H, Orihuela CJ. Sugar-coated killer:

serotype 3 pneumococcal disease. Front Cell Infect

Microbiol 2020;10:613287. Crossref

25. Lo SW, Gladstone RA, van Tonder AJ, et al. Pneumococcal

lineages associated with serotype replacement and

antibiotic resistance in childhood invasive pneumococcal

disease in the post-PCV13 era: an international wholegenome

sequencing study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:759-69. Crossref

26. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 20-valent

pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among U.S. adults:

updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on

Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:109-17. Crossref

27. Essink B, Sabharwal C, Cannon K, et al. Pivotal phase 3

randomized clinical trial of the safety, tolerability, and

immunogenicity of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate

vaccine in adults aged ≥18 years. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:390-8. Crossref

28. Cannon K, Elder C, Young M, et al. A trial to evaluate the

safety and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal

conjugate vaccine in populations of adults ≥65 years of age

with different prior pneumococcal vaccination. Vaccine

2021;39:7494-502. Crossref

29. Mendes D, Averin A, Atwood M, et al. Cost-effectiveness

of using a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

to directly protect adults in England at elevated risk

of pneumococcal disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon

Outcomes Res 2022;22:1285-95. Crossref

30. Mui LW, Chan AY, Lee A, Lee J. Cross-sectional study

on attitudes among general practitioners towards

pneumococcal vaccination for middle-aged and elderly

population in Hong Kong. PLoS One 2013;8:e78210. Crossref