Hong Kong Med J 2022;28(6):475–81 | Epub 11 Jul 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Recommendations for the management of advanced and metastatic renal cell carcinoma: joint consensus statements from the Hong Kong Urological Association and the Hong Kong Society of Uro-Oncology

Darren MC Poon, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1; CK Chan, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Kuen Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)1; WH Chu, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)2; Philip WK Kwong, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1; Wayne Lam, MRCS (Eng), FRCSEd (Urol)2; KS Law, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)1; Eric KC Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Radiology)1; PL Liu, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Henry CK Sze, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1; Joseph HM Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Eddie SY Chan, MD, FHKAM (Surgery)2

1 Hong Kong Society of Uro-Oncology, Hong Kong

2 Hong Kong Urological Association, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Darren MC Poon (darren.mc.poon@hksh.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Kidney cancer, primarily renal cell

carcinoma (RCC), ranks among the top 10 most

common malignancies in the male population of

Hong Kong. In 2019, members of two medical

societies in Hong Kong formed an expert panel

to establish a set of consensus statements for the

management of metastatic RCC. On 22 June 2021,

the same panel met to review recent evidence and

reassess their positions regarding the management

of advanced and metastatic RCC, with the aim of

providing recommendations for physicians in Hong

Kong.

Participants: The panel included 12 experts (6 clinical oncologists and 6 urologists) who had extensive experience managing patients with RCC in Hong Kong.

Evidence: The panel reviewed randomised

controlled trials, observational studies, systematic

reviews/meta-analyses, and international clinical

guidelines to address key clinical questions that were

identified before the meeting.

Consensus Process: In total, 15 key clinical

questions were identified before the meeting,

covering the surgical and systemic treatment of

advanced or metastatic clear cell, sarcomatoid, and

non-clear cell RCCs. At the meeting, the panellists

voted on these questions, then discussed relevant

evidence and practical considerations.

Conclusions: The treatment landscape for

advanced and metastatic RCC continues to evolve.

More immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)–based

combination regimens will be indicated for the

treatment of metastatic clear cell RCC. There is

increasing evidence concerning the benefit of

adjuvant ICI treatment for resected advanced RCC.

This article summarises recent evidence and expert

insights regarding a series of key clinical questions

about the management of advanced and metastatic RCC.

Introduction

In 2018, kidney cancer was the ninth most common malignancy in the male population of Hong Kong,

with a relative frequency of 3%.1 The predominant

type of kidney cancer is renal cell carcinoma (RCC),

which mainly comprises the clear cell subtype; non-clear

cell RCC can be subdivided into papillary,

chromophobe, and other rarer forms (eg, collecting

duct).2 Many RCCs are found incidentally without

symptoms suggestive of malignancy; approximately

30% of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.2

The management of advanced and metastatic

RCC has been transformed by the development of

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine

kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and, more recently, immune

checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). In 2019, members of

two medical societies in Hong Kong formed an expert

panel to establish a set of consensus statements for

the management of metastatic RCC.3 Since then,

the treatment landscape has continued to change

with the addition of two evidence-based ICI-TKI combination therapies: nivolumab/cabozantinib and

pembrolizumab/lenvatinib.4 5 There is also increasing

research concerning the role of adjuvant ICI in the

treatment of advanced RCC after nephrectomy.6

Considering these advances, the same expert panel

met to review recent evidence and reassess their

positions regarding the management of advanced

and metastatic RCC through panel votes on a series

of key clinical questions, with the aim of providing

treatment recommendations for physicians in Hong

Kong.

Methods

The meeting was held on 22 June 2021; the expert panel included 12 clinicians (6 clinical oncologists

and 6 urologists) who had extensive experience

managing patients with RCC in the public or

private healthcare sectors. Prior to the meeting, the

panel identified 15 key clinical questions (online supplementary Appendix) regarding the surgical

and systemic treatment of advanced or metastatic

clear cell, sarcomatoid, and non-clear cell RCCs

in various risk categories. The panel reviewed

randomised controlled trials, observational studies,

systematic reviews/meta-analyses, and international

clinical guidelines that addressed these clinical

questions. Prior to the meeting, review materials

had been identified through a search of the PubMed

database for publications from January 2020 to May 2021 using the key words ‘metastatic/advanced

+ renal cell carcinoma’; the search results were

supplemented with additional articles solicited by the

panellists. At the meeting, the panellists voted on the

15 questions, then discussed relevant clinical

evidence and practical considerations for real-world

clinical practice. The full voting record for each

question is provided in the online supplementary Appendix.

Results

First-line systemic therapies for clear cell

metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Current published evidence

To decide on a treatment strategy for clear cell metastatic RCC, the International Metastatic

RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) risk category7

remains a key consideration. Current international

guidelines largely recommend ICI-containing

combination treatment as the standard of care

for metastatic RCC in all IMDC risk categories

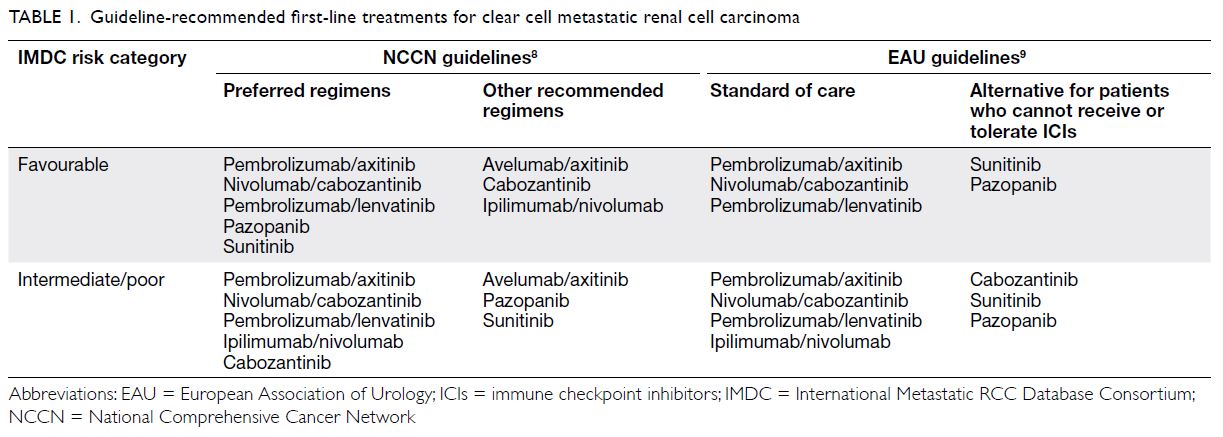

(Table 1).8 9 In phase III open-label randomised

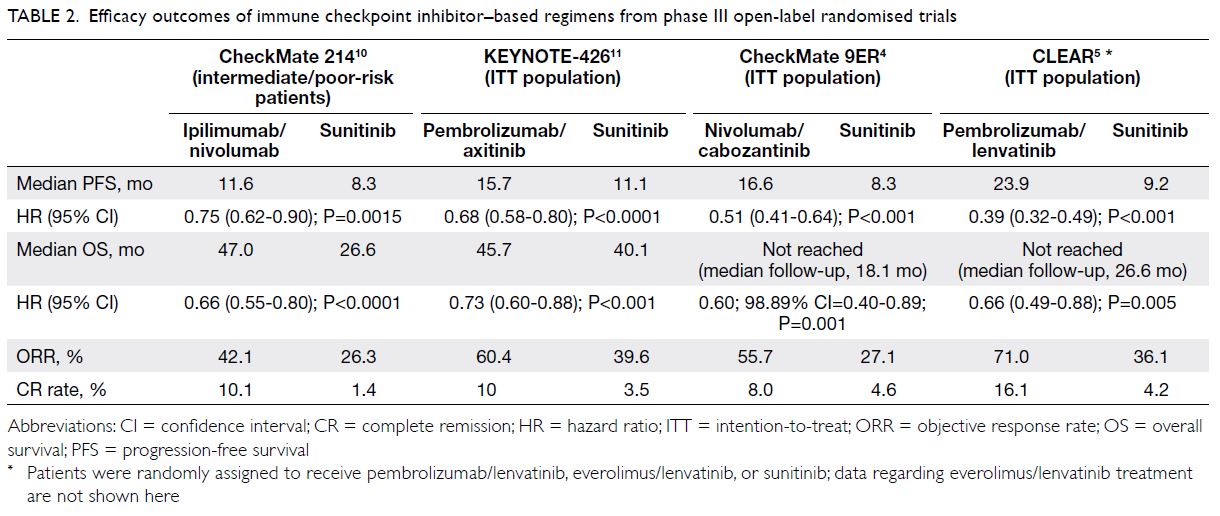

trials, the recommended ICI-containing regimens

significantly improved progression-free survival

(PFS), overall survival (OS), and objective response

rates (ORRs), when compared with sunitinib as first-line

treatment for metastatic RCC in the respective

primary study populations: for intermediate/poor-risk patients, ipilimumab/nivolumab10; and

for intention-to-treat patients, pembrolizumab/axitinib,11 nivolumab/cabozantinib,4 and

pembrolizumab/lenvatinib5 (Table 2). Post-hoc

analyses showed that ipilimumab/nivolumab and

nivolumab/cabozantinib were associated with

better health-related quality of life compared with

sunitinib12 13; there were no significant differences in

health-related quality of life between sunitinib and

pembrolizumab/axitinib or between sunitinib and

pembrolizumab/lenvatinib.14 15

Table 2. Efficacy outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor–based regimens from phase III open-label randomised trials

Recommendations from the expert panel

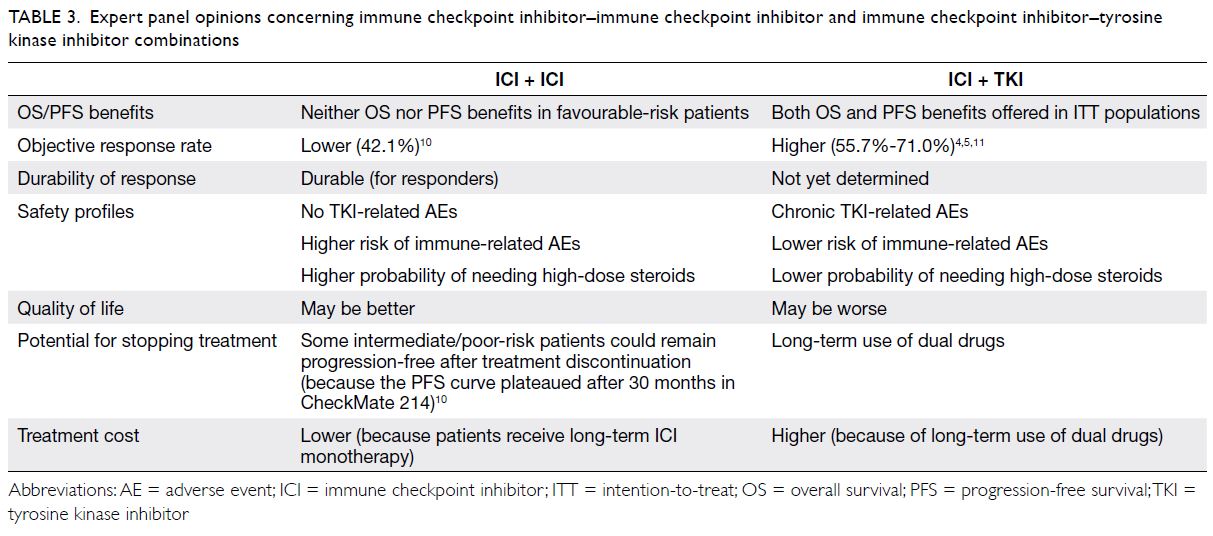

Based on the available evidence and insights from the expert panel, ICI-ICI (ie, ipilimumab/nivolumab)

and ICI-TKI combinations each have specific

advantages and disadvantages (Table 3 4 5 10 11), which

should be considered when selecting a treatment regimen.

Table 3. Expert panel opinions concerning immune checkpoint inhibitor–immune checkpoint inhibitor and immune checkpoint inhibitor–tyrosine kinase inhibitor combinations

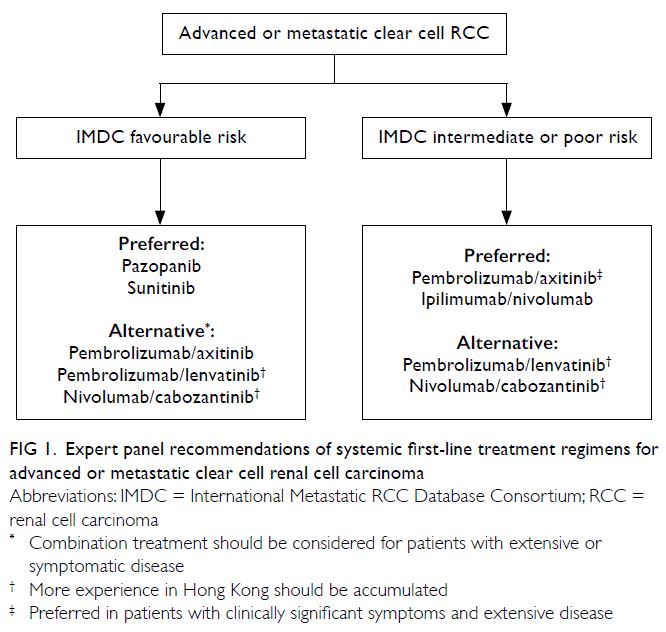

According to the panel consensus, the IMDC risk category and burden of disease or presence of

symptoms were regarded as the most important

patient/disease factors when selecting the first-line

treatment regimen for advanced or metastatic clear

cell RCC. Efficacy (primarily OS, followed by PFS

and ORR) and toxicity were regarded as the most

important treatment-related factors when selecting a

treatment regimen. Figure 1 illustrates the treatment

algorithm recommended by the panel.

Figure 1. Expert panel recommendations of systemic first-line treatment regimens for advanced or metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma

For IMDC favourable-risk advanced or

metastatic clear cell RCC, TKI monotherapy

(pazopanib or sunitinib) was regarded as the

preferred treatment regimen. In subgroup analyses

of phase III open-label randomised trials, the OS

benefits of ICI-TKI combinations were uncertain

in favourable-risk patients, but these results should

be interpreted cautiously because the numbers of

participants were limited in each subgroup.4 5 16

Despite the uncertain OS benefits, ICI-TKI

combinations provided significant PFS and ORR

benefits compared with sunitinib; therefore, they

may remain useful in favourable-risk patients,

particularly patients with extensive or symptomatic

disease who desire treatment with a higher ORR.

For IMDC intermediate/poor-risk advanced

or metastatic clear cell RCC, ICI-based combination

treatment (preferably pembrolizumab/axitinib

or ipilimumab/nivolumab) is recommended. In

patients with clinically significant symptoms and

extensive disease, pembrolizumab/axitinib may

be preferred because it appeared to offer stronger

antitumour activity (ORR, 60.4%; stable disease rate,

22.9%; progressive disease rate, 11.3%) compared

with ipilimumab/nivolumab, according to the

KEYNOTE-426 study.11 In the CheckMate 214 study,

approximately 20% of patients experienced disease

progression after treatment with ipilimumab/nivolumab.10

With respect to newer ICI-TKI combinations (ie, pembrolizumab/lenvatinib and nivolumab/cabozantinib), there is a need to accumulate

additional experience in Hong Kong. The optimal

dose and tolerability profile of lenvatinib, particularly

in Asian patients, should be further investigated; in

the CLEAR study, 70% of patients required dose

reductions for lenvatinib.5 For cabozantinib, there

is a lack of flexibility in dose manipulation; only

60 mg, 40 mg, and 20 mg were available for use in

the CheckMate 9ER study.4 In contrast, the dosage

of axitinib is readily adjustable; 1-mg increments

or reductions can be implemented depending on

patient tolerability.

In public hospitals in Hong Kong, ICIs for the treatment of RCC remain self-financed, whereas TKI

monotherapy (ie, axitinib, pazopanib, and sunitinib)

is supported by the Safety Net programme.17

Adjuvant treatment after nephrectomy in

patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma

Current evidence regarding adjuvant

pembrolizumab treatment

Nephrectomy is the standard of care for localised RCC; however, patients with advanced RCC are

at risk of disease recurrence, and thus the use

of adjuvant treatment warrants investigation. In

the KEYNOTE-564 phase III trial, patients with

high-risk, fully resected clear cell RCC (M0 or M1

without evidence of disease) were randomised to

receive adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo.6 At the

median follow-up interval of 24 months, adjuvant

pembrolizumab significantly improved disease-free

survival compared with placebo (77.3% vs 68.1% at

24 months; hazard ratio [HR]=0.68, 95% confidence

interval [CI]=0.53-0.87; P=0.002 [two-sided]). While

the OS data were immature, there was a trend

in favour of adjuvant pembrolizumab (96.6% vs

93.5% at 24 months; HR=0.54; 95% CI=0.30-0.96).

These results suggest that adjuvant pembrolizumab

can prevent relapse after surgery in patients with

advanced RCC.

Recommendations from the expert panel

The panellists noted that the use of adjuvant systemic

treatment after nephrectomy depends on patient

preference after a discussion of the benefits and

risks. The limitations of adjuvant treatment include

the lack of clear markers of efficacy, the risks of

overtreatment and toxicity (particularly in older and

frailer patients), and the potential for fewer available

treatment regimens in patients who experience

disease recurrence. Compared with adjuvant TKI,

adjuvant ICI may be associated with fewer adverse

effects and better quality of life, offering new

treatment opportunities for high-risk patients (eg,

with nodal metastases). Further studies are needed

to investigate the clinical benefit of adjuvant ICI in distinct patient subgroups (eg, patients with

non-clear cell RCC or bone oligometastases) and

to explore a risk-adapted approach for optimising

patient selection.

Treatment remains investigational for

patients who develop metastatic disease after

receiving adjuvant pembrolizumab. The panellists

favoured TKI monotherapy (pazopanib or

sunitinib), particularly for patients with a short

relapse-free period (eg, <6 months) after adjuvant

pembrolizumab treatment. They noted that patients

with a longer relapse-free period may receive ICI-based

combination treatment; for example, the

antitumour activity of pembrolizumab/lenvatinib in

ICI-pre-treated patients with clear cell metastatic

RCC (ORR, 55.8%) was demonstrated in a phase

I/IIb study.18

Treatment for advanced or metastatic

renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid de-differentiation

The standard of care for sarcomatoid RCC has not been determined. Consistent with the previous

consensus statement, the panellists favoured an

ICI-containing combination for the treatment of

metastatic RCC with sarcomatoid de-differentiation,

which is generally within the IMDC intermediate/poor-risk category. Compared with other RCCs

that lack sarcomatoid features, sarcomatoid

RCCs have higher programmed death-ligand 1

expression; thus, they may be more responsive to ICI

immunotherapies.19 In subgroup analyses of phase

III randomised studies, ICI-containing regimens

offered OS, PFS, and ORR benefits compared with

sunitinib in patients who had metastatic RCC

with sarcomatoid de-differentiation.20 Phase III

randomised trials dedicated to the treatment of

sarcomatoid RCC are expected.

Cytoreductive nephrectomy

Consistent with the previous consensus statement, the panellists favoured systemic treatment, rather

than upfront cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN), for

the management of de novo metastatic RCC.

The CN candidacy in IMDC favourable-risk

patients remains unclear, particularly in the ICI era.

Several panellists noted that CN may be irrelevant

to this patient population because most will have

already undergone nephrectomy or decided to

avoid nephrectomy based on age and performance

status, considering that the time from their diagnosis

until systemic treatment is ≥1 year. However, when

immediate systemic treatment is not required,

upfront CN with metastasectomy may be considered

for patients with asymptomatic primary tumours

and limited metastases confined to the lung. There is

also preliminary evidence to support the use of CN combined with ICI immunotherapy in patients with

pathologically favourable tumour characteristics.

An analysis of the United States National Cancer

Database found that, in patients with metastatic

RCC, the combination of CN (primarily in the

upfront setting) and ICI immunotherapy improved

median OS (not reached vs 11.6 months; HR=0.23,

P<0.001) compared with ICI immunotherapy

alone.21 Because ICI-based combination treatment is increasingly used, the role and sequence of CN warrant prospective validation.

The panellists recommended deciding whether

to perform CN in IMDC intermediate-risk patients

based on the extent of disease and symptoms.

Upfront CN may be considered for patients with

solitary or limited metastases (oligometastases).

Otherwise, delayed CN may be considered for

patients who respond well to systemic treatment.

Further studies are required to explore the patient

selection and optimal timing for CN in the context

of ICI immunotherapy.

The panellists recommended avoiding CN in

IMDC poor-risk patients, considering their low life

expectancy (7-8 months) and poor prognosis, as

well as the potential for surgical complications and

impacts on quality of life. Retrospective data from

the IMDC demonstrated that poor-risk patients did

not experience survival benefits from CN.22

Treatment for advanced or metastatic non-clear

cell renal cell carcinoma

The standard of care for metastatic non-clear cell

RCC remains unclear, particularly considering the

heterogeneity among subtypes. Based on the current

evidence, the panellists favoured TKI monotherapy

(cabozantinib or sunitinib). In a randomised open-label

phase II trial, patients with metastatic papillary

RCC were randomly assigned to receive sunitinib,

cabozantinib, crizotinib, or savolitinib; only

cabozantinib improved median PFS compared with

sunitinib (9.0 vs 5.6 months; HR=0.60 [95% CI=0.37-0.97], one-sided P=0.019).23 The antitumour activity of sunitinib in metastatic non-clear cell RCC has

been demonstrated in prospective studies.24 25

Subsequent treatment for advanced or

metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma

after progression on first-line systemic treatment

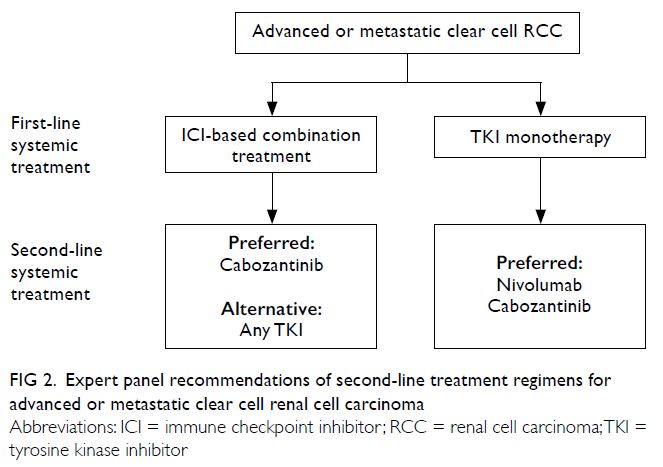

While the optimal sequence of treatment remains

unclear, the principle of choosing a subsequent

treatment (Fig 2) is consistent with the previous

consensus statement. In patients who demonstrated

progression after ICI-based combination treatment,

the panellists favoured TKI monotherapy, primarily

cabozantinib; its antitumour activity in patients

with prior exposure to ICIs has been demonstrated in large retrospective studies.26 27 In patients who

demonstrated progression after first-line TKI

monotherapy, the panellists favoured nivolumab

or cabozantinib based on prospective evidence,28,29

which was described in the previous consensus

statement.

Figure 2. Expert panel recommendations of second-line treatment regimens for advanced or metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Conclusions

The treatment landscape for advanced and metastatic RCC is evolving. More ICI-based combination

regimens have recently been shown to offer survival

benefits, compared with TKI monotherapy, as first-line

systemic treatment in patients with metastatic

clear cell RCC. There is increasing evidence to

support the feasibility of adjuvant ICI treatment after

surgery in patients with advanced RCC. This article

has summarised recent evidence and insights from

an expert panel on a series of key clinical questions,

with the goal of optimising the management of

advanced and metastatic RCC in Hong Kong. These

recommendations are expected to undergo regular

review and updating, considering that several crucial

areas (eg, the role of CN combined with ICI-based

treatment, the standard of care for RCCs with

sarcomatoid features or non-clear cell histology,

and the optimal sequence of systemic treatments)

require further investigation.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept and/or design of the

study, acquisition of the data, analysis and/or interpretation

of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision

of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All

authors have had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Best Solution Company Limited, Hong Kong, for providing medical writing/editorial support, which was funded by the Hong Kong Urological Association.

Funding/support

Medical writing/editorial support and the panel meeting for voting and discussions were funded by the Hong Kong

Urological Association.

References

1. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Available from: https://www3.

ha.org.hk/cancereg/. Accessed 7 Jul 2021.

2. Cairns P. Renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark 2010;9:461-73. Crossref

3. Poon DM, Chan CK, Chan K, et al. Consensus statements

on the management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma

from the Hong Kong Urological Association and the Hong

Kong Society of Uro-Oncology 2019. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol

2021;17(Suppl 3):27-38. Crossref

4. Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021;384:829-41. Crossref

5. Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1289-300. Crossref

6. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab after nephrectomy in renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021;385:683-94. Crossref

7. Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors

for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell

carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted

agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J

Clin Oncol 2009;27:5794-9. Crossref

8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN guidelines kidney cancer. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1440. Accessed 28 Jun 2021.

9. European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma/. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

10. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Survival

outcomes and independent response assessment with

nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in patients

with advanced renal cell carcinoma: 42-month follow-up

of a randomized phase 3 clinical trial. J Immunother

Cancer 2020;8:e000891. Crossref

11. Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro)

plus axitinib (axi) versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for

advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC): results

from 42-month follow-up of KEYNOTE-426. J Clin Oncol

2021;39 (Suppl 15):4500. Crossref

12. Cella D, Grünwald V, Escudier B, et al. Patient-reported

outcomes of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma

treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib

(CheckMate 214): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol 2019;20:297-310. Crossref

13. Cella D, Choueiri TK, Blum SI, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC) treated with first-line nivolumab plus cabozantinib

versus sunitinib: the CheckMate 9ER trial. J Clin Oncol

2021;39(Suppl 6):285. Crossref

14. Bedke J, Rini B, Plimack E, et al. Health-related

quality-of-life (HRQoL) analysis from KEYNOTE-426:

pembrolizumab (pembro) plus axitinib (axi) vs sunitinib

for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Proceedings

of the 35th Annual EAU Congress–Virtual; 2020 July 19;

Game changing session 4.

15. Motzer RJ, Porta C, Alekseev B, et al. Health-related

quality-of-life (HRQoL) analysis from the phase 3 CLEAR

trial of lenvatinib (LEN) plus pembrolizumab (PEMBRO)

or everolimus (EVE) versus sunitinib (SUN) for patients

(pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC). J Clin

Oncol 2021;39(Suppl 15):4502. Crossref

16. Powles T, Plimack ER, Soulières D, et al. Pembrolizumab

plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line

treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-426): extended follow-up from a randomised, open-label,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1563-73. Crossref

17. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Drug

formulary management. Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/hadf/en-us/. Accessed 9 Jul 2021.

18. Lee CH, Shah AY, Rasco D, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with either treatment-naive or previously treated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (Study

111/KEYNOTE-146): a phase 1b/2 study. Lancet Oncol

2021;22:946-58. Crossref

19. Blum KA, Gupta S, Tickoo SK, et al. Sarcomatoid renal cell

carcinoma: biology, natural history and management. Nat

Rev Urol 2020;17:659-78. Crossref

20. Buonerba C, Dolce P, Iaccarino S, et al. Outcomes

associated with first-line anti-PD-1/ PD-L1 agents vs.

sunitinib in patients with sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel)

2020;12:408. Crossref

21. Singla N, Hutchinson RC, Ghandour RA, et al. Improved

survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the contemporary immunotherapy

era: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. Urol

Oncol 2020;38:604.e9-17. Crossref

22. Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, et al. Cytoreductive

nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases

from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International

Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium.

Eur Urol 2014;66:704-10. Crossref

23. Pal SK, Tangen C, Thompson IM Jr, et al. A comparison

of sunitinib with cabozantinib, crizotinib, and savolitinib

for treatment of advanced papillary renal cell carcinoma: a

randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021;397:695-703. Crossref

24. Armstrong AJ, Halabi S, Eisen T, et al. Everolimus versus

sunitinib for patients with metastatic non-clear cell

renal cell carcinoma (ASPEN): a multicentre, open-label,

randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:378-88. Crossref

25. Tannir NM, Jonasch E, Albiges L, et al. Everolimus versus

sunitinib prospective evaluation in metastatic non-clear

cell renal cell carcinoma (ESPN): a randomized multicenter

phase 2 trial. Eur Urol 2016;69:866-74. Crossref

26. Iacovelli R, Ciccarese C, Facchini G, et al. Cabozantinib

after a previous immune checkpoint inhibitor in metastatic

renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective multi-institutional

analysis. Target Oncol 2020;15:495-501. Crossref

27. McGregor BA, Lalani AA, Xie W, et al. Activity of

cabozantinib after immune checkpoint blockade in

metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer

2020;135:203-10. Crossref

28. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, George S, et al. Nivolumab

versus everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell

carcinoma: Updated results with long-term follow-up of

the randomized, open-label, phase 3 CheckMate 025 trial.

Cancer 2020;126:4156-67. Crossref

29. Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib

versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma

(METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:917-27. Crossref