© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Doctor’s bag belonging to Dr Wai-cheung Chau

Winnie Tang, MB, BS

Member, Educational and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

These days, to get medical advice from a medical

doctor in Hong Kong, it is usually necessary to go

to a clinic or hospital, but this was not always the

case. In the past, especially in rural and isolated

areas, doctors would visit patients at home; in some

regions outside of Hong Kong, such home visits are

still routine medical practice. To provide correct

diagnosis and treatment during a home visit, a

doctor must carry all the essential equipment and

medications for any circumstance that might arise.

Thus, a doctor’s bag must be strong, reliable, and

easy to carry, with the ability to be opened widely for

easy access to the contents.

Medical practitioners have been carrying such

bags since ancient times, with the first mention of

a doctor’s bag recorded in the Hippocratic Corpus

known as ‘Decorum’, dated to about 350 BCE.1

The type of cases or bags that doctors carried has

changed over time, depending on requirements and

situations, as well as the newest technologies and

fashions. For example, early doctors had wooden or

leather chests mainly for surgical instruments that

were brought on navy ships or taken to war with

the army. Doctors in the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries often used saddle bags, because the doctors

travelled to the patient’s home on foot or by horse.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the familiar

doctor’s bag based on the Gladstone bag became

widely adopted. These bags are made of stiff leather

over a wooden frame, with a large opening at the top

to allow convenient access.

This doctor’s bag (Fig 1) belonged to Dr Waicheung

Chau (周懷璋醫生). Dr Chau graduated

from the medical school at The University of Hong

Kong in 1916. He worked in public service after

graduation for 2 years at Ho Miu Ling Nethersole

Hospital and Tai Po Dispensary.2 In 1923, he wrote

in the journal of the Hong Kong University Medical

Society, Caduceus, describing his experience of

working in Tai Po Dispensary.3 He had been called to

attend to a patient who had delivered at home 3 days

prior in a hut in Sheung Shui, which was rural Hong

Kong at that time. She had copious loss of blood

because of a retained placenta. Dr Chau was able to

save the patient by removing the placenta piecemeal

while the patient was under chloroform anaesthesia

administered by the midwife who accompanied him. From his account, we can deduce that Dr Chau

brought with him the necessary equipment and

medications to make this possible.

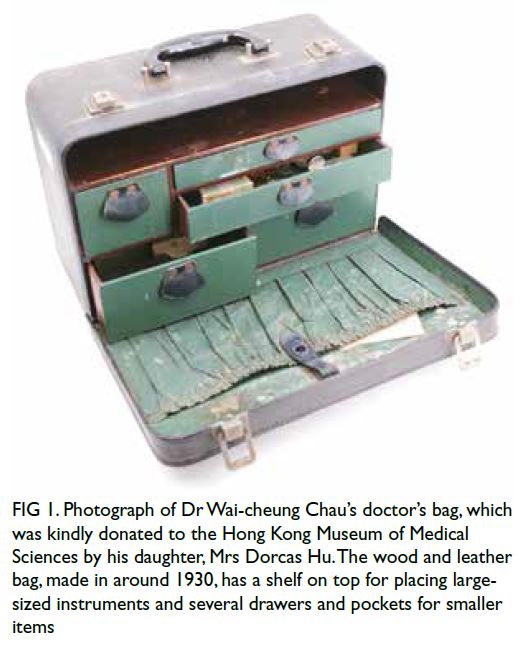

Figure 1. Photograph of Dr Wai-cheung Chau’s doctor’s bag, which was kindly donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by his daughter, Mrs Dorcas Hu. The wood and leather bag, made in around 1930, has a shelf on top for placing large-sized instruments and several drawers and pockets for smaller items

Dr Chau later worked in private practice, first

in his own private clinic and then at Hong Kong

Sanatorium & Hospital. At that time, house calls

were routine, especially for those too weak to attend

his clinic, and he would have carried this bag, made

around 1930. Unlike the Gladstone-style doctor’s

bags, Dr Chau’s bag is rectangular, similar to a small

suitcase, 35.6 cm (14”) wide, 24.1 cm (9.5”) tall,

and 14.6 cm (5.75”) deep. The bag has a wooden

frame, is lined with thin leather on the outside, has

two metal clasps, a plastic handle on top, and four

metal studs on the bottom. The inside is lined with

waterproof paper and divided into different-sized

compartments, some with drawers with leather flap

handles. The lid is lined with fabric and leather, and

has some pockets for securing small items.

The contents inside a doctor’s bag varied with

the type of practice of the doctor, but were invariably

tools for diagnosis and medication for treatment.1 4

Diagnostic instruments carried in a doctor’s bag

always included a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer,

a clinical thermometer, a tongue depressor, and some

form of illumination such as a flashlight. Depending

on the patients’ symptoms, the doctor might also

carry other tools, such as a tuning fork, a percussion

hammer, an otoscope, or an ophthalmoscope.

Syringes, needles, cotton wool in spirit, gloves,

dressings, bandages, catheters, and test tubes were

also carried as required. In Dr Chau’s bag, there were

boxes of glass slides for him to prepare smears for

further pathological examination. As technology

improved, some of these items, such as syringes,

needles, gloves, and lancets, were replaced with

disposable versions, and test strips replaced the

bulky laboratory apparatus.

Medication carried in a doctor’s bag was

varied, including drugs for emergency use or for

preventive use. In the nineteenth century, doctors

even carried vaccines to patients’ homes for smallpox

inoculation.4 Although there are often new or more

advanced drugs produced, a doctor’s bag always

carried some core drugs, including antimicrobials,

sedatives, analgesics, anti-asthmatics, anti-allergics,

hormones, cardiac stimulants, and vitamins and

minerals. In Dr Chau’s bag, there was a variety of

medicines. Most drugs carried in a doctor’s bag were

for parenteral administration, and stored in rubber-stoppered

vials, glass ampoules, or hypodermic

tablets in small glass tubes, to be dissolved or boiled

before injection (Fig 2). The parenteral route enabled

the drug to work fast enough for the doctor to observe

the effect and assess whether he could safely leave

the patient after treatment. Further medications, if

required, would be collected from the doctor’s clinic

the next day.

Figure 2. Photograph of some of the medicines from Dr Chau’s doctor’s bag in vials and ampoules, which are stuck to a plate. The tube on the right contains hypodermic tablets of strychnine sulphate, to be boiled in water before injection

Paperwork for home visits was usually simple,

and doctor’s bags usually had only small notepads

for writing prescriptions or clinical records. In Dr

Chau’s bag, there were name cards and envelopes in

the pockets.

As the population of Hong Kong ages, and the

number of homebound individuals increases, there

may be a change in demand for home visits. In the

past 3 years, many medical facilities and services were unavailable because of measure to mitigate the

spread of COVID-19. Thus, many patients had to, or

chose to, isolate themselves at home. Doctors were

called to see patients at care homes for the elderly

or at their private residences, especially at the peak

of the pandemic in Hong Kong in the first half of

2022. Many of these found themselves more at ease

with healthcare service delivered to their residence.

Although home visits by doctors are unlikely to

return to the mainstream as they once were, there

may be increased demand for home visits in future.

If home visits do regain popularity, it is

likely that the doctor’s bag will also enjoy a

resurgence. However, the form will have to evolve

to accommodate modern technology and adapt

to different settings of the patient’s residence,

similar to the bags carried by modern paramedics.

Traditional Gladstone-style doctor’s bags are now

more of a fashion item, and designers have taken

elements from the original bags, modernising and

making stylish briefcases, travel bags, purses, or

handbags. The few remaining original doctor’s bags

have become collectable antique items or museum

exhibit, with some still retaining aromas from the

medicines they once carried.

References

1. Dammery D. A historical account of the doctor’s bag. Aust Fam Physician 2016;45:636-8.

2. Ho FC. Some unusual and some outstanding personalities. In: Ho FC, editor. Western Medicine for Chinese: How

the Hong Kong College of Medicine Achieved a Breakthrough. HKU Press; 2017: 161-3. Crossref

3. Chau WC. Two cases of difficult labour. Caduceus 1923;2:44-5.

4. Low JA. The doctor’s bag in 1911. CMAJ 2012;184:E100-2. Crossref