Hong Kong Med J 2022 Dec;28(6):494–5.e1-3

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

A critically ill infant with multi-organ dysfunction due to eczema

KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; WL Lin, PhD, BChinMed2; David CK Luk, MB, ChB, MRCPCH3

1 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Hong Kong Institute of Integrative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Eczema is the most prevalent childhood atopic

illness routinely encountered by health professionals

providing care to children.1 Some infants become

critically ill and present to the paediatric intensive

care unit (PICU) with this seemingly trivial

condition.2 This anonymised (no clinical and

laboratory data are presented) case of severe eczema

and multi-organ dysfunction illustrates the extent of multi-organ involvement in eczema and the medical

and psychosocial issues associated with the disease.1 3

A 6-month-old boy with eczema and septic

shock presented to the emergency department. He

was treated with fluid resuscitation and subsequently

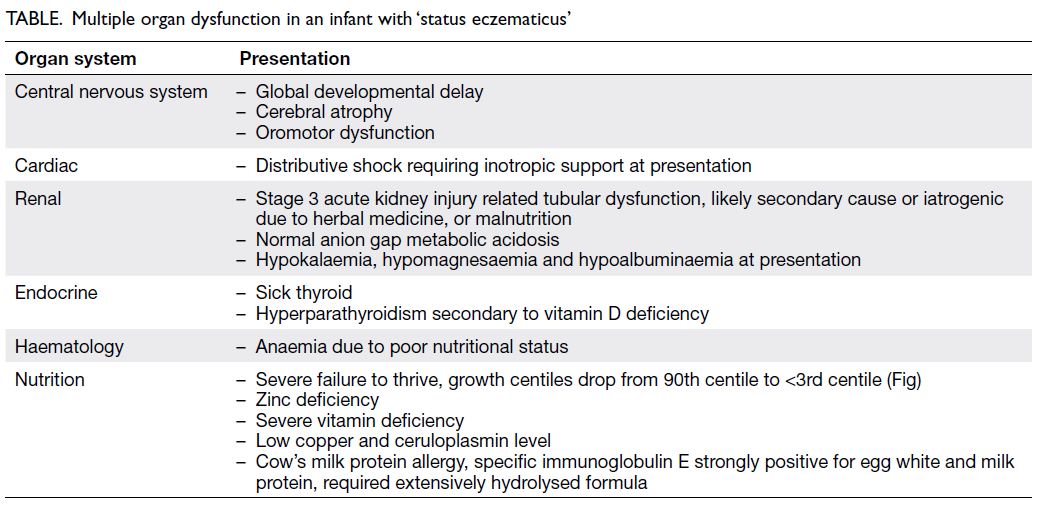

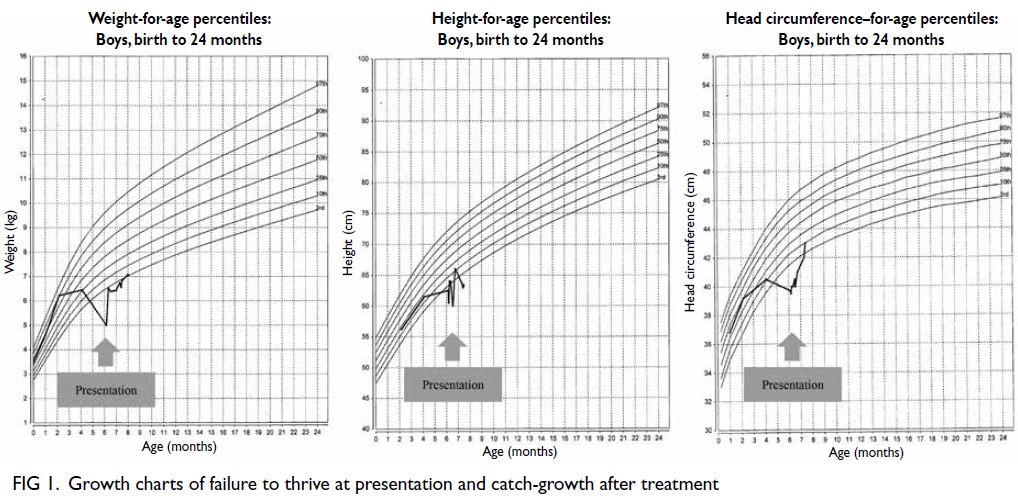

admitted to a PICU. Derangement of multiple

organ functions were identified along with failure to

thrive and poor development (Table, Figs 1 and 2). Dobutamine and broad-spectrum antibiotics were

prescribed. Although his condition improved

rapidly, it became apparent that his parents did

not trust Western medicine and were reluctant to

use emollient and topical steroid to manage their

child’s eczema. The mother frankly admitted that

since the development of eczema at 2 months of

age, she had been giving the infant complementary

herbal medicine remedies. She was also taking

herbal medicine whilst breastfeeding so that her

child would indirectly receive the more ‘effective’

herbal medicine. The parents were interviewed by

healthcare workers from various disciplines but they

remained resolute in their beliefs and phobias about Western medicine. The child was discharged from

PICU after the acute medical issues were resolved.

Extensive investigations have been performed

and apart from persistent peripheral eosinophilia,

slightly low immunoglobulin M level, borderline

CD4:CD8 ratio and borderline low zinc level, all

other investigations including metabolic workup

remain unremarkable to date. Further paediatric

dermatology, genetics and integrative medicine

follow-ups have been arranged.

Our reported case is probably the youngest

patient with critical ‘status eczematicus’ to survive.

All growth parameters were compromised (Fig 1).

Children with severe eczema rarely require admission

to an ICU and there are very few such cases in the

literature. Mortality due to eczema is rare, but we

have previously reported a tragic case of an infant

with eczema who died of group B streptococcus

septicaemia and malnutrition despite expensive

dietary supplements.2 Eczema is a chronic condition

that can significantly affect a child’s quality of life as

well as that of their family if it is not well controlled

due to the potentially significant psychological toll.4

Although ICU is not an ideal setting to manage a

family with multiple phobias, the child must first be

stabilised, and other differential diagnoses of acute

skin failure ruled out.2

Acute treatment of eczema is straightforward

but long-term maintenance treatment is always

challenging. Topical medications should be

considered to prevent exacerbations and therapy

should be proactive. Steroid phobia is prevalent and

often leads to non-compliance.1

Recommendations about dietary avoidance

should be specific and given only in confirmed

cases of food allergy.1 The use of traditional and

proprietary topical and herbal medicine is popular

across many countries in Asia.1 Anxious food-avoiding

parents may purchase multi-vitamin

supplements, prebiotics, probiotic or symbiotics

that claim to be effective. In an extreme case, death

was reported to have a secondary association with

extreme dietary practice.3 Physicians must be tactful

when counselling these anxious parents who are

steroid phobic and mistrusting of modern medicine.

Indirect administration of herbal medicine to an

infant through breastfeeding is not advocated even

in the practice of integration medicine.

Management of eczema can sometimes be

challenging. Apart from strong parental beliefs,

cultural differences might also play a role in

compliance with a prescribed treatment plan or

a tendency to seek alternative therapies instead.

These effects are likely to be underestimated in

our community, especially in the primary care

setting where consultation time might be limited.

Physicians should endeavour to spend more time

exploring parental beliefs. A practical solution may be to use an objective self/parental assessment to

aid eczema control assessment, eg, ‘Traffic Light

Control’ self-assessment system (Fig 3) and quality

of life assessment, eg, Children’s Dermatology Life

Quality Index.5 An ‘eczema action plan’ can also be

given to parents to remind them of the prescribed

eczema treatment. The treatment plan should be

straightforward and easy to follow, especially if

they perceive a worsening of eczema between clinic

visits.5 A multidisciplinary and perhaps integrative

medicine approach should be adopted where possible

to manage patients and families with eczema, and

education about the disease should be individualised

to improve patient outcomes.

Healthcare providers must be aware of the

mortality and morbidity associated with recalcitrant

eczema and ‘status eczematicus’. These tragic cases

of ‘status eczematicus’ serve to remind us of the

grave consequences if eczema is inappropriately

managed.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the

manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts

of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the

Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval for publication of

patient information in the paediatric intensive care unit was

obtained from the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital Research

Ethics Committee (Ref No.: HKCH-REC-2019–0011).

References

1. Hon KL, Leong KF, Leung TN, Leung AK. Dismissing

the fallacies of childhood eczema management: Case

scenarios and an overview of best practices. Drugs

Context 2018;7:212547. Crossref

2. Hon KL, Nip SY, Cheung KL. A tragic case of atopic

eczema: malnutrition and infections despite multivitamins

and supplements. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol

2012;11:267-70.

3. Hon KL, Kam WY, Leung TF, et al. Steroid fears in children with eczema. Acta Paediatr 2006;95:1451-5. Crossref

4. Hon KL, Kung JS, Wang M, Pong NH, Li AM, Leung TF.

Clinical scores of sleep loss and itch, and antihistamine

and topical corticosteroid usage for childhood eczema. Br

J Dermatol 2016;175:1076-8. Crossref

5. Lam PH, Hon KL, Leung KK, Leong KF, Li CK, Leung TF. Self-perceived disease control in childhood eczema. J

Dermatolog Treat 2022;33:1459-646. Crossref