Hong Kong Med J 2022 Oct;28(5):409.e1–4

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Breast lymphoma: a rare breast malignancy

mimicking benign breast disease and carcinoma

Carol PY Chien, MB, BS, FRCR1; Kimmy KM Kwok, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)2; Eliza PY Fung, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)2

1 Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Carol PY Chien (chienpyc@gmail.com)

In July 2020, a 52-year-old woman presented with

a 1-month history of palpable right breast lump.

Clinical examination revealed a hard mass at the upper

inner quadrant of the right breast. No skin changes

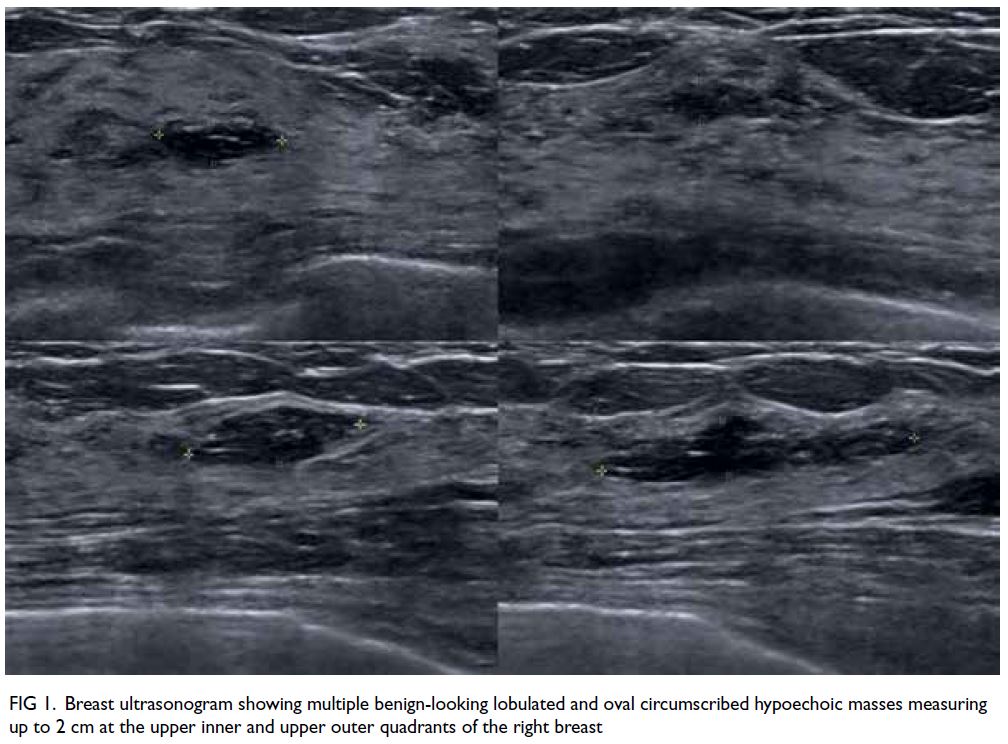

or nipple retraction were evident. Ultrasonography

confirmed multiple oval circumscribed hypoechoic

masses at the upper right breast measuring up to

2 cm that were considered likely benign (Fig 1). The

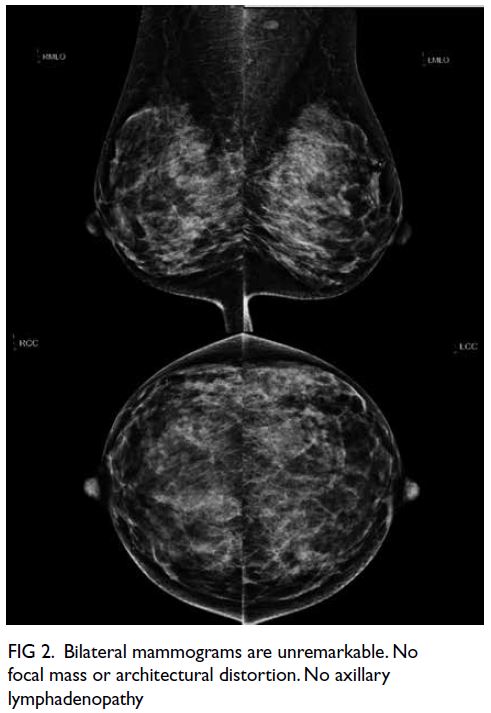

lesions were mammographically occult (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Breast ultrasonogram showing multiple benign-looking lobulated and oval circumscribed hypoechoic masses measuring up to 2 cm at the upper inner and upper outer quadrants of the right breast

Figure 2. Bilateral mammograms are unremarkable. No focal mass or architectural distortion. No axillary lymphadenopathy

The patient also reported non-specific

abdominal pain and distension for a few weeks.

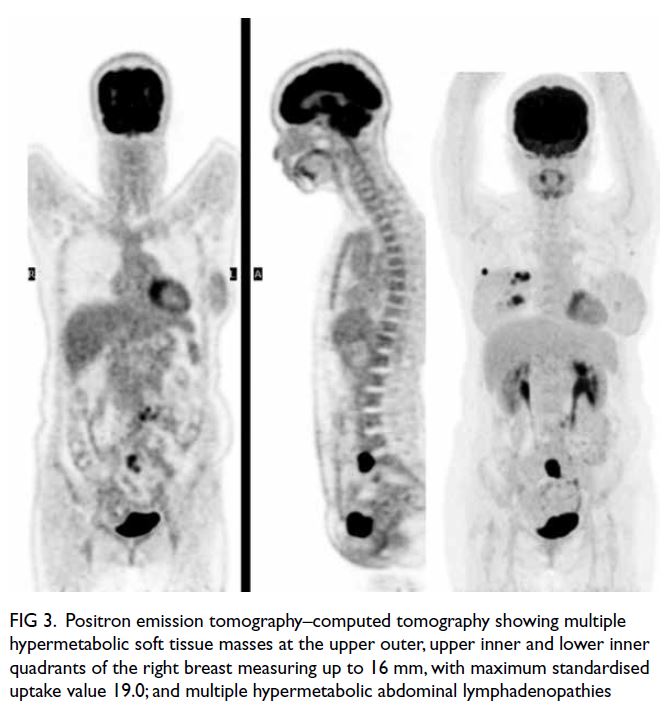

Positron emission tomography–computed

tomography (PET-CT) showed multiple

hypermetabolic masses at the right breast

(maximum standardised uptake value [SUVmax]

19.0, 16 mm) and abdominal lymphadenopathy

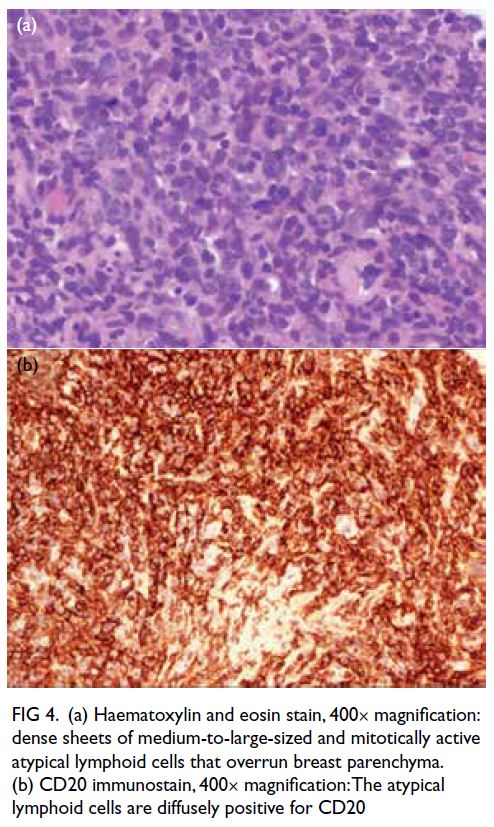

(Fig 3). Ultrasound-guided core biopsy of the right

breast mass confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

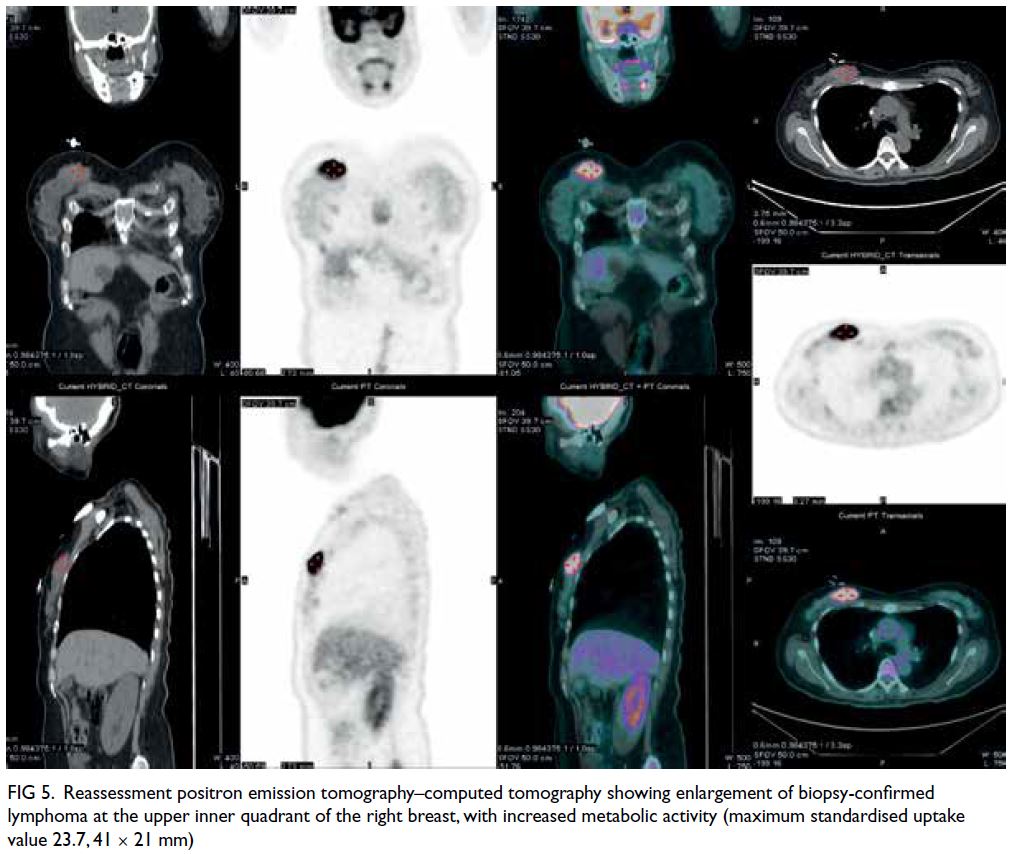

(Fig 4). The patient was diagnosed with stage IV lymphoma with diffuse extranodal involvement of

the right breast. Reassessment PET-CT showed

progressive disease despite R-CEOP chemotherapy

with enlargement and increased metabolic activity

of the right breast lymphoma (SUVmax 23.7, 41 mm)

and abdominal lymphadenopathy (Fig 5). Second-line

chemotherapy and radiotherapy of the breast

was administered.

Figure 3. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showing multiple hypermetabolic soft tissue masses at the upper outer, upper inner and lower inner quadrants of the right breast measuring up to 16 mm, with maximum standardised uptake value 19.0; and multiple hypermetabolic abdominal lymphadenopathies

Figure 4. (a) Haematoxylin and eosin stain, 400× magnification: dense sheets of medium-to-large-sized and mitotically active atypical lymphoid cells that overrun breast parenchyma. (b) CD20 immunostain, 400× magnification: The atypical lymphoid cells are diffusely positive for CD20

Figure 5. Reassessment positron emission tomography–computed tomography showing enlargement of biopsy-confirmed lymphoma at the upper inner quadrant of the right breast, with increased metabolic activity (maximum standardised uptake value 23.7, 41 × 21 mm)

The breast is an uncommon extranodal site

of involvement by lymphoma because of the lack

of lymphoid tissue. Breast lymphoma is a rare

malignancy of the breast that accounts for <1% of

all breast malignancies and <2% of all extranodal

non-Hodgkin lymphoma.1 Diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma is the most common histological type in

both primary and secondary breast lymphoma with

a median age at presentation of 60 to 70 years.1

The clinical presentation of breast lymphoma

is highly variable, so diagnosis is challenging. It commonly presents as a mass that mimics carcinoma,

or skin inflammatory changes that mimic benign

inflammatory breast disease or inflammatory breast

cancer.1 2 Axillary lymphadenopathy is uncommon.1

However, unlike with breast carcinoma, nipple

retraction or discharge and other skin changes are

rare with breast lymphoma.1 2

Mammographically, breast lymphoma

commonly presents as a solitary mass (69%-76%) and asymmetry (20%). It may also present

as skin thickening, architectural distortion or

lymphedema.3 4 In contrast to breast carcinoma,

spiculations, architectural distortion and

microcalcifications are distinctively absent with

breast lymphoma. Sonographically, breast lymphoma

commonly presents as a parallel benign-looking

hypoechoic mass without malignant features.3 4

Ultrasonography alone cannot distinguish breast

lymphoma from breast carcinoma or benign breast

lesions such as fibroadenoma. However, it can guide

tissue diagnosis when mammogram is negative. This

is particularly helpful in Asian patients with dense

breast tissue that lowers mammogram sensitivity.

A recent study has demonstrated that 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

PET-CT can potentially

differentiate between breast lymphoma and

carcinoma.5 The authors found that the median

SUVmax for breast lymphoma (10.96) was

significantly higher than that for breast carcinoma

(4.76; specificity up to 96.3%).5 Although the

sonographic features of breast masses in our patient

were absent, an SUVmax of 19.0 was unusually

high for breast carcinoma. This raised the suspicion

of secondary breast lymphoma rather than

primary breast carcinoma with distant metastases.

Histological diagnosis was required to guide

appropriate treatment.

In conclusion, PET-CT can potentially

differentiate between breast lymphoma and breast

carcinoma. Increased awareness of breast lymphoma

and correlation with radiological and pathological

findings are essential for diagnosis.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: CPY Chien.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CPY Chien.

Drafting of the manuscript: CPY Chien.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: CPY Chien.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CPY Chien.

Drafting of the manuscript: CPY Chien.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided informed consent for all investigations and procedures, and publication.

References

1. Raj SD, Shurafa M, Shah Z, Raj KM, Fishman MD,

Dialani VM. Primary and secondary breast lymphoma:

clinical, pathologic, and multimodality imaging review.

Radiographics 2019;39:610-25. Crossref

2. Sabaté JM, Gómez A, Torrubia S, et al. Lymphoma of the breast: clinical and radiologic features with pathologic correlation in 28 patients. Breast J 2002;8:294-304. Crossref

3. Yang WT, Lane DL, Le-Petross HT, Abruzzo LV, Macapinlac HA. Breast lymphoma: imaging findings of 32

tumors in 27 patients. Radiology 2007;245:692-702. Crossref

4. Surov A, Holzhausen HJ, Wienke A, et al. Primary and

secondary breast lymphoma: prevalence, clinical signs and

radiological features. Br J Radiol 2012;85:e195-205. Crossref

5. Ou X, Wang J, Zhou R, et al. Ability of 18F-FDG PET/CT

radiomic features to distinguish breast carcinoma

from breast lymphoma. Contrast Media Mol Imaging

2019;2019:4507694. Crossref