© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency in chronic

lymphocytic leukaemia: a case report

Andy SO Tang, MD, MRCP (UK)1; QY Wong, MB, BS2; ST Yeo, BPharm (Hon)2; Jenny TH Lee, MB, BS3; TS Leong, MB, BS, MRCP (UK)4; LP Chew, MD, FRCP (UK)4

1 Haematology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Miri Hospital, Ministry of Health, Sarawak, Malaysia

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Miri Hospital, Ministry of Health, Sarawak, Malaysia

3 Department of Pathology, Sarawak General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Sarawak, Malaysia

4 Haematology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Sarawak General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Sarawak, Malaysia

Corresponding author: Dr Andy SO Tang (andytangsingong@gmail.com)

Case report

Acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency is a rare disorder

with varying manifestations and an estimated

prevalence of 1 per 100 000 to 500 000 population.1

We present a case of acquired angio-oedema that

manifested after a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic

leukaemia (CLL).

In June 2017, a 60-year-old man who

was previously healthy was found to have

lymphocytosis on routine health screening. Physical

examination showed multiple lymph nodes with

no hepatosplenomegaly. A lymph node biopsy was

consistent with small lymphocytic lymphoma. Bone

marrow examination revealed small mature-looking

lymphocytes with a background of smudge cells.

The leukaemia cells co-expressed the CD5 antigen

and B-cell surface antigens, with restricted kappa

immunoglobulin light chain expression. Fluorescence

in situ hybridisation analysis demonstrated a

homozygous 13q14.2 gene deletion. Serum kappa and lambda free light chain (FLC) results were

99.50 mg/L (reference 6.70-22.40 mg/L) and

12.50 mg/L (reference 8.30-27.00 mg/L),

respectively, with a kappa to lambda ratio of

7.96. Beta-2 microglobulin level was 4.64 mg/L

(reference 1.09-2.53 mg/L). The patient screened

seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus,

syphilis, and hepatitis B and C. Overall findings

were consistent with a diagnosis of CLL Rai stage II

(Binet stage B), with Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group performance status zero. A ‘wait and watch’

approach was adopted initially until mid-2018

when the patient started to report fatigue and

absolute lymphocyte count doubled in less than

6 months. Owing to limited resources, the patient

was given weekly intravenous rituximab (500 mg)

but developed herpes zoster infection after two

cycles. Treatment was changed to chlorambucil

(8 mg once daily) and prednisolone (20 mg once

daily) for 10 days per cycle, repeating every 28 days,

with acyclovir prophylaxis.

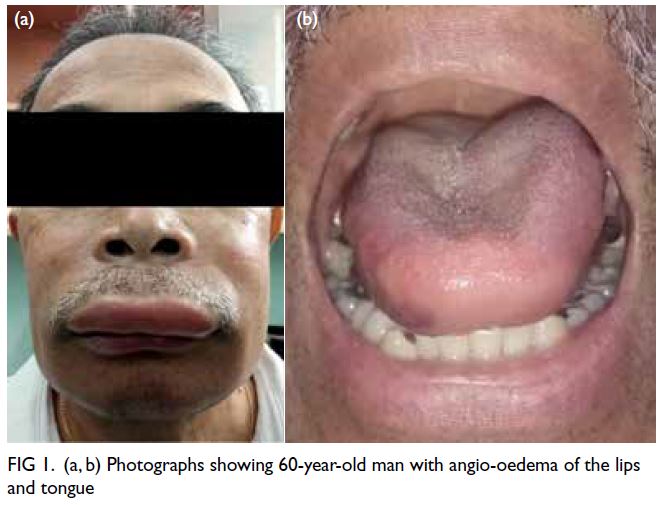

At 1 year after this treatment started, the

patient presented with an acute event of angio-oedema

that began as a tingling around his face and

mouth similar to a bee sting and swelling of his lips

and tongue (Fig 1), sparing the larynx, abdomen,

extremities, and genital involvement. There were

no identifiable inciting episodes. He denied intake

of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,

traditional medications, or over-the-counter drugs.

He had no history of atopy or angio-oedema.

The patient remained well until early 2020

when he presented with similar episodes of angio-oedema

that recurred on three occasions. A complete

workup revealed a C1 esterase inhibitor antigen level

of 4 mg/dL (reference 19-37 mg/dL) with function

being 9% (reference <66%). Complement C1q level

measured using radial immunodiffusion assay was

undetectable with low complement 3 and 4 [0.29 g/L

(reference value 0.9-1.8 g/L), <0.02 g/L (reference

value 0.15-0.45 g/L), respectively]. Owing to

restricted resources, anti-C1 inhibitor antibodies and

monoclonal component isotypes were unavailable. Autoimmune screening (antinuclear antibody and

rheumatoid factor) and serum cryoglobulin were

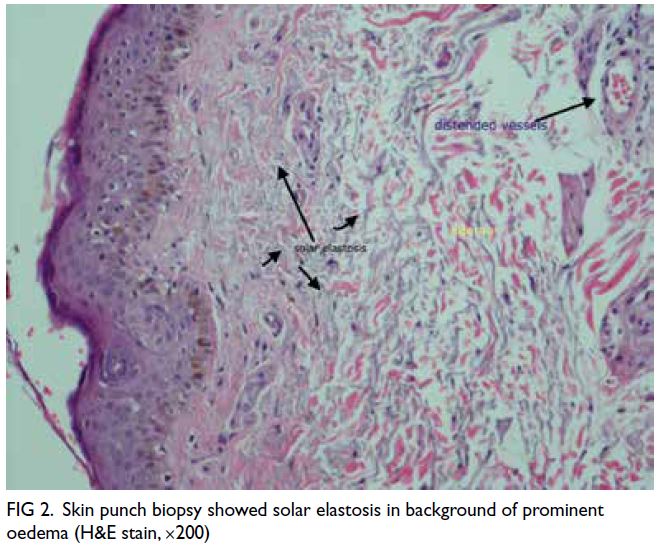

negative. Skin biopsy showed features of angio-oedema

without atypical lymphocytes (Fig 2).

During the fourth acute attack of angio-oedema, the

patient was given tranexamic acid and danazol and

symptoms completely resolved within 24 hours.

Figure 2. Skin punch biopsy showed solar elastosis in background of prominent oedema (H&E stain, ×200)

The overall clinical manifestations and

laboratory findings were consistent with the diagnosis

of acquired angio-oedema due to C1 deficiency

in association with CLL. We decided to initiate

chemotherapy—rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

vincristine, and prednisolone. After two cycles, the

patient developed urticaria vasculitis over his limbs

that responded to cetirizine and resolved completely

after completing six cycles of chemotherapy. C1

esterase inhibitor functional assay normalised. He

remained free of any recurrent angio-oedema and

urticaria during the 1-year follow-up period. He was

able to resume work and could live independently.

Discussion

Angio-oedema can be hereditary or acquired.

The latter often presents after the fifth decade of

life with no family history.1 Symptom onset and

absence of family history led to a diagnosis of

acquired angio-oedema in our patient due to C1

esterase inhibitor deficiency. The median time to

diagnosis is reported to vary between 10 months

and 10 years.2 Our patient was diagnosed 9 months

after symptom onset and during the third episode

of angio-oedema. To the best of our knowledge, only about 20 cases of CLL have been reported to

be associated with angio-oedema.2 Many diseases

are reported to be associated with acquired angio-oedema,

with lymphoproliferative disorders and

B-cell malignancies the most common.3

In acquired angio-oedema, C1 esterase

inhibitor protein level is decreased due to excessive

consumption, or may be dysfunctional due to the

presence of antibodies against C1 inhibitor, leading

to defective inhibition of the complements and kinin

system. This results in exaggerated response in the

classic complement pathway and production of

bradykinin leading to angio-oedema, in which C1q

and C4 level is low, as in our case.2 Our patient also

developed urticaria vasculitis. This was likely due to

C1q depletion and low complement, as previously

reported.2 Urticaria vasculitis, which likely involves

tumour-associated immune complexes, has been

described as a rare association with haematological

malignancy.4 The achievement of disease remission

led to resolution of both angio-oedema and urticarial

vasculitis in our case.

Our patient demonstrated a kappa-restricted

serum FLC with the summated FLC being 112 mg/L,

confirming the monoclonal nature of serum FLC.

Studies have shown that serum FLC may be elevated

in almost 50% of patients with CLL. This finding is

an adverse prognostic factor for time to treatment

and overall survival.5

The mainstay of treatment for acute acquired

angio-oedema includes C1 esterase inhibitor

concentrate from human plasma or recombinant

C1 inhibitor concentrate.3 Nonetheless these

products are not widely available in most healthcare

facilities, including our centre where fresh frozen

plasma is a reasonable alternative, although not

without potential risks. Long-term prophylactic

treatment with antifibrinolytic agents and danazol

has been shown to be equally efficacious,2 with

a recommendation to avoid the former in the

presence of thromboembolic risk factors.2 It is vital

to treat the underlying disease to prevent acute

attacks, regardless of the treatment options.2 Our

patient has had no further attacks of angio-oedema

after receiving rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

vincristine, and prednisolone chemotherapy. This

is in concordance with the literature that reports

resolution of angio-oedema after treatment of the

underlying malignancy.4

Our case highlights the challenge posed in

managing a patient with CLL and atypical features.

Clinical suspicion should be heightened in patients

who present with recurrent episodes of angio-oedema.

Treating the underlying malignancy often

leads to complete resolution of symptoms.

Author contributions

Concept or design: ASO Tang, TS Leong, LP Chew.

Acquisition of data: ASO Tang, JTH Lee, QY Wong, ST Yeo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JTH Lee, QY Wong, ST Yeo.

Drafting of the manuscript: ASO Tang, TS Leong, LP Chew.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: ASO Tang, JTH Lee, QY Wong, ST Yeo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JTH Lee, QY Wong, ST Yeo.

Drafting of the manuscript: ASO Tang, TS Leong, LP Chew.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial disclosure.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia and Clinical Research Centre (CRC) Miri

Hospital for permission to publish this paper.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This article does contain studies with human participants and was registered via National Medical Research Register Malaysia with a Research ID of NMRR-20-1666-56020.

The patient(s) provided written informed consent for all

treatments and procedures and consent for publication.

References

1. Pappalardo E, Cicardi M, Duponchel C, et al. Frequent

de novo mutations and exon deletions in the C1inhibitor

gene of patients with angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2000;106:1147-54. Crossref

2. Gobert D, Paule R, Ponard D, et al. A nationwide study of

acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency in France: characteristics

and treatment responses in 92 patients. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2016;95:e4363. Crossref

3. Cicardi M, Zingale LC, Pappalardo E, Folcioni A, Agostoni A.

Autoantibodies and lymphoproliferative diseases in

acquired C1-inhibitor deficiencies. Medicine (Baltimore)

2003;82:274-81. Crossref

4. Marder RJ, Rent R, Choi EY, Gewurz H. C1q deficiency

associated with urticarial-like lesions and cutaneous

vasculitis. Am J Med 1976;61:560-5. Crossref

5. Sarris K, Maltezas D, Koulieris E, et al. Prognostic

significance of serum free light chains in chronic

lymphocytic leukemia. Adv Hematol 2013;2013:359071. Crossref