Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:32–6 | Number 1, February 2014 | Epub 9 Jan 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133952

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Occlusion therapy in amblyopia: an experience from Hong Kong

Emily WH Tang, FRCSEd1;

Brian CY Li, MB, ChB1;

Ian YL Yeung, MRCS (Ed), MRCOphth1,2;

Kenneth KW Li, FRCSEd1,2

1 Department of Ophthalmology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong,

Hong Kong

2 Eye Institute, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr EWH Tang (etang@graduate.hku.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To review the results of patching for

amblyopia management in Hong Kong.

Design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: Regional hospital, Hong Kong.

Patients: Records of all patients attending Paediatric

Ophthalmology Clinic at United Christian Hospital,

Hong Kong from 1 January 2009 to 31 March

2009 were retrospectively reviewed. Records of all

children who underwent patching for amblyopia in

the study period were evaluated.

Results: The mean age of 50 children (50 eyes)

was 4 (standard deviation, 1; range, 2-7) years and

mean pretreatment visual acuity was 0.35 (0.15;

0.02-0.63) [~20/60]. The values for mean, standard

deviation, and range of treatment duration were

27, 16, 4-67 months respectively, and corresponding values for

prescribed patching per day were 4, 1, 2-8 hours.

The mean, standard deviation, and range of visual

acuity at final post-treatment assessment were 0.66,

0.16, 0.1-1.0 (~20/30), respectively. The overall success rate (ie

final visual acuity >0.7 or 20/30) was 62%. Children

with moderate amblyopia (20/40-20/80) and severe

amblyopia (20/100-20/400) had success rates of

74% and 55%, respectively. The mean visual acuity

improvements for moderate and severely amblyopic

children were 2.3 lines and 5.8 lines, respectively.

The mean, standard deviation, and range of patching

prescriptions for moderate and severely amblyopic children were 5, 1, 2-7 hours and 5, 1, 3-6 hours,

respectively. Recurrence ensued in 7% of the children

with moderate amblyopia and 46% of those with

severe amblyopia. Reported compliance was good

(>75% of the time) in 68% of the children.

Conclusion: Occlusion therapy is the mainstay

of treatment in Hong Kong. The overall success

rate was comparable to that achieved in the

Amblyopia Treatment Study. Recurrence was more

common in patients with severe amblyopia, for

whom maintenance therapy may reduce the risk of

recurrence. The duration of treatment was much

longer in our locality than in western countries.

Reported compliance was suspicious possibly due

to traditional cultural contexts. It is important to

emphasise compliance to all parents.

New knowledge added by this

study

- The Amblyopia Treatment Study (ATS) result cannot be directly applied to Hong Kong children. Heavier dosage for moderate amblyopia and longer treatment for both moderate and severe amblyopia appear necessary for successful treatment of affected Hong Kong children.

- The current practice for occlusion therapy in Hong Kong should not be changed to ATS recommendations; maintenance therapy should be considered with a view to reducing recurrences in children with severe amblyopia (visual acuity 20/100 to 20/400).

Introduction

Amblyopia is the most common cause of monocular

visual impairment in both children and young adults.1 2

Since year 2002, the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator

Group has undertaken various randomised controlled

trials, known as the Amblyopia Treatment Study

(ATS). The ATS has provided insights into how

amblyopia can be most effectively managed with

respect to aspects such as dose response, the required amount of prescribed occlusion, compliance with

treatment, use of atropine, and the upper age limit for treatment.3 4 5 6

Despite recent research on amblyopia treatment,

studies show that the uptake of ATS guidelines and

their results into clinical practice are sporadic and

incomplete in both the UK and the US.7 Apparently,

one third of paediatric ophthalmologists have made

no changes whatsoever to their practice. Other studies found that 55% of paediatric ophthalmologists

had decreased their prescribed patching regimens,

which was contrary to ATS recommendations.8 9

In Hong Kong, patching is still the mainstay of

treatment for unilateral amblyopia. Yet, the impact

of the ATS guidelines on clinical practice is also

inadequate. In our locality, prescriptions for patching

are usually based on the age of the child. The duration

and subsequent dosages are tapered or adjusted

according to the individual child’s response and visual

acuity (VA) improvement. Our study therefore aimed

to compare current amblyopia management and

results of patching at a government hospital in Hong

Kong against the guidelines and results reported in

the ATS.

Methods

This was a retrospective case series study, for which

approval was obtained from the local research

ethics committee. Records of all children attending

the Paediatric Ophthalmology Clinic at the United

Christian Hospital, Hong Kong from 1 January 2009

to 31 March 2009 were reviewed. All children who had received patching for amblyopia were identified.

Two patients with structural abnormalities due to

cataract and retinal pathologies, one with bilateral

amblyopia warranting alternating patching, and three

others with incomplete data or follow-up of less than

3 months were excluded. In all, 50 patients (50 eyes)

were therefore identified and relevant demographic

data were obtained.

Patching protocol

Visual acuity was measured using Sheridan Gardiner

test for patients aged under 4 years and Snellen charts

for those 4 years old or older. Optical correction was

provided for all patients before commencement of

patching. Refraction with or without cycloplegia was

performed for the optical correction, which followed

our departmental guidelines, at the discretion of the

attending optometrist. Children were deemed to

require cycloplegic refraction if they had unreliable

retinoscopy or autorefraction readings (the very

young, the uncooperative, or having pseudomyopia);

accommodative esotropia; extreme refractive errors

(especially myopia); anisometropia (>2 dioptres); or

suspected amblyopia with >3 lines of difference in

VA.

Prescription of patching was based on the

age of the child, and the number of hours per day

corresponded to the age. For instance, 3 hours per

day for a 3-year-old and 5 hours per day for a 5-year-old.

Patching duration was titrated according to the

patient’s response and improvement of VA. Patching

therapy was stopped when the best-corrected visual

acuity (BCVA) of the amblyopic eye caught up or

equalled that of the fellow eye, or when the patient

reached 8 years old. Maintenance therapy was given

to patients with severe pretreatment amblyopia after

successful patching therapy and those with recurrent

amblyopia. Such prescriptions were for 2 hours per

day for around 6 to 8 months. Patients were regularly

reviewed every 3 to 4 months to monitor treatment

response including VA, refractive errors, compliance,

recurrence, and occurrence of occlusion amblyopia.

Outcome and statistical analysis

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the 50

patients were collected and analysed. Data relating

to BCVA before and after patching, duration and

intensity of patching, and compliance (percentage

subjectively reported by parents) were collected and

analysed.

Snellen VA was converted to equivalent logMAR

vision for statistical analysis. Treatment success was

defined as a BCVA of 20/30 (0.7) or better. Improved

VA in both the moderate and severe amblyopia groups

were compared with the corresponding ATS 2B and

ATS 2A study groups, respectively. All statistical

analysis was performed using statistical software

(Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; Windows version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). The paired

t test, independent t test and Mann-Whitney U test

were used as appropriate, and a P value of less than

0.05 was considered significant.

Results

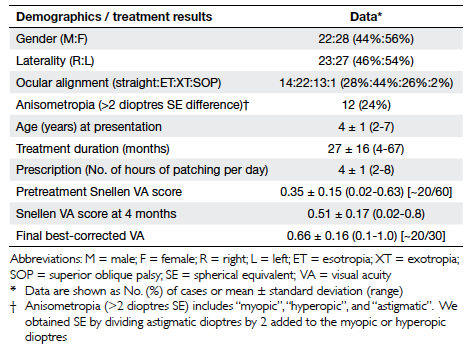

The demographic data and treatment results of the

50 patients are shown in Table 1. There were 42

patients with moderate (20/40-20/80) and severe

amblyopia (20/100-20/400) as defined by the ATS.

The overall success rate (ie final VA >0.7 or 20/30)

was 62% (31/50); respective success rates in those

with moderate (20/40-20/80) and severe amblyopia

(20/100-20/400) were 74% (23/31) and 55% (6/11).

The mean VA improvement at 4 months for moderate

and severe amblyopia children was 1.0 lines and 6.0

lines, respectively. The mean final VA improvement

for the moderately and severely amblyopic children

was 2.3 and 5.8 lines, respectively. The respective

mean ± standard deviation of moderately and severely

amblyopic children for the following outcome

measures were: patching prescription, 5 ± 1 (range,

2-7) hours/day and 5 ± 1 (range, 3-6) hours/day; and

patching duration, 23 ± 13 (range, 6-57) months and

38 ± 15 (range, 19-66) months. Reported compliance

was good (>75% of the time) in 68% (n=34), fair

(50-75% of the time) in 22% (n=11), and poor (<50%

of the time) in 18% (n=5) of the children. Visual

outcomes in relation to patient compliance in patients

with moderate and severe amblyopia are shown in

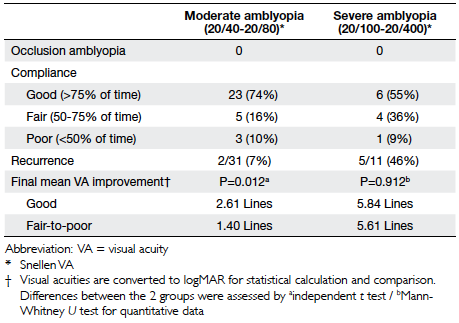

Table 2.

Table 1. Demographic data and treatment results of children with unilateral amblyopia attending Paediatric Ophthalmology Clinic in United Christian Hospital between January 2009 and March 2009

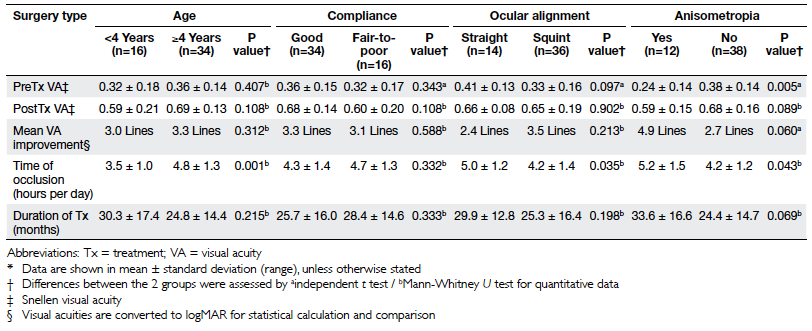

Subgroup comparisons

There were no significant differences in mean VA

improvement between children (i) aged <4 (n=16)

and ≥4 (n=34) years; (ii) having good (n=34) and fair-to-poor (n=16) compliance; and (iii) with straight

(n=14) and squint (n=36) eyes (Table 3).

Table 3. Subgroup patient comparisons according to age, compliance, ocular alignment, and presence of anisometropia*

Regarding subgroup comparison for

anisometropia (n=12) and non-anisometropia (n=38)

groups, the former achieved significantly better mean

VA improvements (4.9 vs 2.7 lines, P=0.060). There

was no difference in the duration of treatment in the

two groups (Table 4).

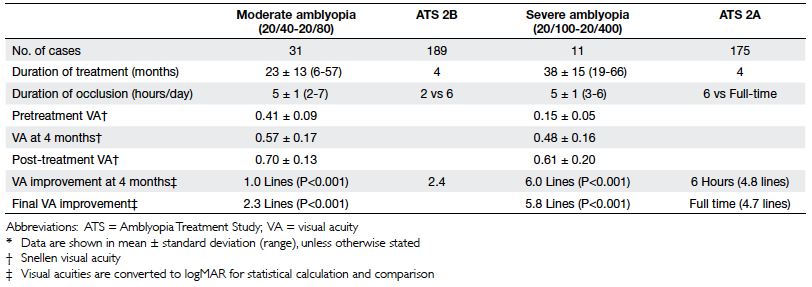

Table 4. Treatment duration and Snellen visual acuity outcomes with reference to the Amblyopia Treatment Study 2 (for children aged 3 to 7 years)*

Discussion

Amblyopia is a common condition in paediatric

ophthalmology, which is potentially reversible if

early treatment is given. It is an important condition

warranting efforts to maximise children’s visual

potential during their age of visual plasticity. In

our locality, the first-line treatment after refractive

correction is patching. Although ATS showed similar

results with patching as with atropine treatment,10 11

most parents in Hong Kong regard patching more

acceptable than atropine, because the latter usually

causes visual blurring and may affect the academic performance. This is an important consideration

for Hong Kong children who are often busy with

schoolwork, including ample near work. Adverse

reactions to atropine (flushing and fever) are also

common in this locality which also make this form of

treatment less popular.

Notably, the children in our series received

much longer durations of patching treatment

than those in ATS (27 vs 4 months), though the

final VA improvements were similar (Table 4).

In those with severe amblyopia, the mean VA

improvement at 4 months was slightly greater than

the final improvement. For severe amblyopia, 45% of the children (5/11) were assessed by the Sheridan

Gardiner test (suitable for children <4 years old) at

4 months instead of Snellen Acuity charts, though

the latter are considered more accurate. All 11

children were using Snellen Acuity charts during

the final VA assessment. Maintenance therapy might

have extended the treatment duration in certain

cases. Assuming Caucasian and Asian eyes as well

as environmental visual stimuli were similar, poor

compliance could be why longer patching therapy

was used to achieve similar VA improvements,

even after exclusion of structural abnormalities and

correction of refractive errors. In fact, the reported

compliance for occlusion therapy has been found to

be poor in other studies.12 13 The reported compliance

in our case series (68%) was good but suspicious.

Due to cultural reason, over-reporting of good

compliance was possible in our society. Traditionally,

the Chinese regard modest lies more positively than immodest truths.14 Hence, some parents may have

overstated the hours of occlusion. A similar situation

prevails when we deal with the compliance to anti-glaucomatous

eyedrops, in which the reasons for

medication non-adherence are complex and may

be societal rather than only medical.15 16 Objective

measurement of patching compliance and risk

factors analysis might be preferable for future studies.

Emphasis on compliance to patching is important to

communicate when commencing treatment and at

every subsequent follow-up visit.

Notably, recurrence was much more common

in patients with severe amblyopia (46%) than in those

in whom it was moderate (7%). This was consistent

with the ATS 2C results.6 Tapering of patching to

maintain therapy instead of abrupt termination may

help to reduce the risk of recurrence.

There was a concern about overtreatment, as

our dosages were much higher than those in ATS 2B (5 hours/day vs 2 hours/day) for moderate amblyopia.

Yet, no occlusion amblyopia was observed in our case

series. We believe vigilant and close monitoring of

the VA can avoid overtreatment.

Since this was a retrospective study, our case

series had several limitations, which included small

sample size, non-standardised treatment protocol,

heterogeneity of case mix, and lack of a control arm.

Nonetheless, this study supports the effectiveness

of the current Hong Kong practice for amblyopia

treatment by patching.

Conclusion

Our study showed treatment success rates comparable

to those of ATS for moderate amblyopia (74% vs 79%

in ATS 2B) and in all children (62% vs 62% in ATS

1). However, larger dosages for moderate amblyopia

and longer treatments for both moderate and

severe amblyopia appeared necessary for successful

treatment in Hong Kong children. Early treatment is

important. Maintenance therapy may help to reduce

recurrences in children with severe amblyopia. It

seems that ATS result cannot be directly applied to

Hong Kong children. It is important to emphasise

compliance to all parents.

References

1. Matta NS, Singman EL, Silbert DI. Evidenced-based

medicine: treatment for amblyopia. Am Orthopt J

2010;60:17-22. Crossref

2. Cools G, Houtman AC, Spileers W, Van Kerschaver E,

Casteels I. Literature review on preschool vision screening.

Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 2009;(313):49-63.

3. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized

trial of atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate

amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:268-78. Crossref

4. Holmes JM, Kraker RT, Beck RW, et al. A randomized trial

of prescribed patching regimens for treatment of severe amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology 2003;110:2075-87. Crossref

5. Repka MX, Beck RW, Holmes JM, et al. A randomized trial

of patching regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia

in children. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:603-11. Crossref

6. Holmes JM, Beck RW, Kraker RT, et al. Risk of amblyopia

recurrence after cessation of treatment. J AAPOS

2004;8:420-8. Crossref

7. Newsham D. The effect of recent amblyopia research on

current practice in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:1352-7. Crossref

8. Wygnanski-Jaffe T. The effect on pediatric ophthalmologists

of the randomized trial of patching regimens for treatment

of moderate amblyopia. J AAPOS 2005;9:208-11. Crossref

9. Wygnanski-Jaffe T, Levin AV. The effect of the randomized

trial of patching regimens for treatment of moderate

amblyopia on pediatric ophthalmologists: 3-year outcome.

J AAPOS 2007;11:469-72. Crossref

10. Holmes JM, Beck RW, Kraker RT, et al. Impact of

patching and atropine treatment on the child and family

in the amblyopia treatment study. Arch Ophthalmol

2003;121:1625-32. Crossref

11. Felius J, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, et al. Evaluating the

burden of amblyopia treatment from the parent and child’s

perspective. J AAPOS 2010;14:389-95. Crossref

12. Stewart CE, Moseley MJ, Stephens DA, Fielder AR. Treatment

dose-response in amblyopia therapy: the monitored

occlusion treatment of amblyopia study (MOTAS). Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:3048-54. Crossref

13. Newsham D. Parental non-concordance with occlusion

therapy. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:957-62. Crossref

14. Fu G, Brunet MK, Lv Y, et al. Chinese children’s moral

evaluation of lies and truths—roles of context and parental

individualism-collectivism tendencies. Infant Child Dev

2010;19:498-515.

15. Friedman DS, Okeke CO, Jampel HD, et al. Risk factors for

poor adherence to eyedrops in electronically monitored

patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2009;116:1097-105. Crossref

16. Wu HY, Yin JF. Clinical investigation of medication

adherence of glaucoma patients [in Chinese]. Zhonghua

Yan Ke Za Zhi 2010;46:494-8.