Hong Kong Med J 2022 Aug;28(4):294–9 | Epub 28 Jan 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effects of strict public health measures on

seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during pregnancy

Hillary HY Leung, MB, BS, BSc1; Christy YT Kwok, BMBS1; Daljit S Sahota, BEng, PhD1; Maran BW Leung, PhD1; Grace CY Lui, MB, ChB (Hons), PDipID2; Susanna SS N, g, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)3; WC Leung, MB, BS, MD (HKU)4; Paul KS Chan, MB, BS, MD (CUHK)2; Liona CY Poon, MB, BS, MD (Res) (University of London)1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Division of Respiratory Diseases, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: (liona.poon@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: A substantial number of people

infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) remain asymptomatic

throughout the course of infection. Nearly half of

pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) are asymptomatic upon diagnosis; these

cases are not without risk of maternal morbidity.

Here, we investigated the seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in an unselected sample of

pregnant women in Hong Kong.

Methods: This prospective cohort study included

pregnant women who presented for routine Down

syndrome screening (DSS) between November 2019

and October 2020; all women subsequently delivered

at the booking hospitals. Serum antibodies against

SARS-CoV-2 were analysed using a qualitative

serological assay in paired serum samples taken at

DSS and delivery for all participants.

Results: In total, 1830 women were recruited.

Six women (0.33%) were seropositive at the DSS

visit; this seropositivity persisted until delivery. Of

the six women, none reported relevant symptoms

during pregnancy; one reported a travel history

before DSS and one reported relevant contact

history. The interval between sample collections

was 177 days (range, 161-195). Among women

with epidemiological risk factors, 1.79% with travel

history, 50% with relevant contact history, and 0.77%

with community SARS-CoV-2 testing history, were seropositive.

Conclusion: The low seroprevalence in this study

suggests that strict public health measures are

effective for preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

However, these measures cannot be maintained

indefinitely. Until a highly effective therapeutic

drug targeting SARS-CoV-2 becomes available,

vaccination remains the best method to control the

COVID-19 pandemic.

New knowledge added by this study

- The seroprevalence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (anti–SARS-CoV-2) antibodies in an unselected sample of pregnant women in Hong Kong was low.

- Public health measures are effective for limiting the transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

- Anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies persist for at least 6 months.

- Serological testing could be utilised at antenatal screening to confirm the presence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, preferably acquired through vaccination; such antibodies would provide some protection for the pregnant woman and her baby during the remaining portion of the pregnancy.

Introduction

A substantial number of people infected with severe

acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) remain completely asymptomatic throughout

the course of infection.1 In a recent prospective observational study of maternal and neonatal

complications among 2130 pregnant women with

and without SARS-CoV-2 infection, 44% of pregnant

women diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) were asymptomatic upon diagnosis. Despite this asymptomatic status, they exhibited

increased risks of maternal morbidity (relative

risk=1.24; 95% confidence interval=1.00-1.52) and

pre-eclampsia (relative risk=1.63; 95% confidence

interval=1.01-2.63), compared with pregnant women

who had not been diagnosed with COVID-19.2 In a

retrospective cohort study conducted in Spain, 3.1%

of 759 pregnant women exhibited anti–SARS-CoV-2

antibodies and had been asymptomatic throughout

pregnancy.3 Serological testing may serve as a useful

tool to identify pregnant women who have recovered

from a recent asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection;

this information can help guide the management of

potential future complications.

Before the imposition of strict border control,

a large number of people travelled between Hong

Kong and the rest of the world each day. Pregnant

women could have been infected without their

knowledge because of asymptomatic or very mild

disease. Furthermore, pregnancy symptoms can

mask some COVID-19 symptoms, particularly if the

COVID-19 symptoms are mild.4 In this study, we

invited women who had undergone Down syndrome

screening (DSS) since November 2019 to ascertain

the seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

in an unselected sample of pregnant women in Hong

Kong. The findings were expected to provide insights concerning the asymptomatic infection rate among

pregnant women.

Methods

This prospective cohort study included pregnant

women who presented for routine DSS and

underwent routine blood sample collection at 11 to

13 weeks of gestation between November 2019 and

October 2020. All participants delivered at Kwong

Wah Hospital or Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong

Kong; the last delivery occurred in March 2021.

Eligibility criteria included consent to serum storage

for future research purposes and intention to deliver

at the booking hospital. Eligible women who attended

the booking hospital for delivery were invited to

participate in the study. Women who delivered

elsewhere, experienced pregnancy termination or

miscarriage, or received a diagnosis of COVID-19

before the study were excluded. Women who agreed

to participate in the study were asked to provide

written informed consent for blood collection at

delivery. Symptoms of COVID-19 throughout the

pregnancy were evaluated at recruitment and at

delivery.

Serum antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were

analysed using a qualitative serological assay.

Qualitative detection of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

(immunoglobulin G [IgG] and immunoglobulin M

[IgM]) directed against the nucleocapsid protein

(N-protein) of the virus was performed using the

Elecsys Anti–SARS-CoV-2 assay (Roche, United

States) on a Cobas®e411 analyser. The result

was provided as a cut-off index (COI). A positive

anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody result was defined as

COI >=1.0. Individuals who had recovered from

COVID-19 were recruited as positive control cases

(COI >=1.0); individuals who had negative SARS-CoV-2

test results were recruited as negative control cases

(COI <1.0) to ensure quality control in the anti–SARS-CoV-2 immunoassay.

Positive results based on qualitative detection

of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were subsequently

confirmed by quantitative measurements of IgG

and IgM antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike

protein by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assays (ImmunoDiagnostics Limited, Hong Kong).

All tests were performed in duplicate, in accordance

with the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were

interpreted as negative when the optical density was

<0.2 and as positive when the optical density was

>=0.2. For samples with positive results, anti–spike

protein concentrations (ng/mL) were calculated.

Continuous variables were expressed

as medians (interquartile ranges or ranges).

Categorical variables were summarised as counts

and percentages. SPSS Statistics (Windows version

26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States) was

used for data analyses.

The STROBE reporting guidelines were used

during the preparation of this manuscript.

Results

In total, 3219 consecutive pregnant women were

approached; 306 declined participation and 1083

were excluded, including two with laboratory-confirmed

SARS-CoV-2 infection, 69 who

experienced miscarriage or pregnancy termination,

and 1012 who planned delivery elsewhere. Thus,

1830 women were recruited to the study and

provided written informed consent to participate.

In total, 1810 (98.9%) women were Chinese, and

852 (46.6%) women were nulliparous. The median

(interquartile range) maternal weight, height and

age were 55.5 kg (50.3-62.5), 159 cm (155-163) and

33.0 years (30.2-36.4), respectively.

In total, six women (0.33%) were seropositive

(COI >=1) at the DSS visit; this seropositivity persisted

until delivery. Among these six women, one exhibited

both anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies;

the IgM antibodies were undetectable at delivery.

The remaining seropositive women exhibited only

anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies at both visits. All

six of these women reported no relevant symptoms

during pregnancy. Among the six women, one

reported a travel history before her first DSS and one

reported relevant contact history. The median COIs were 2.465 (interquartile range=1.430-3.178) and

1.680 (interquartile range=1.145-2.350) at DSS and

delivery, respectively. The interval between sample

collections was 177 days (range, 161-195). The COI

at delivery was lower by a median of 31.8% (range,

12.0-35.1), compared with the COI at the DSS visit.

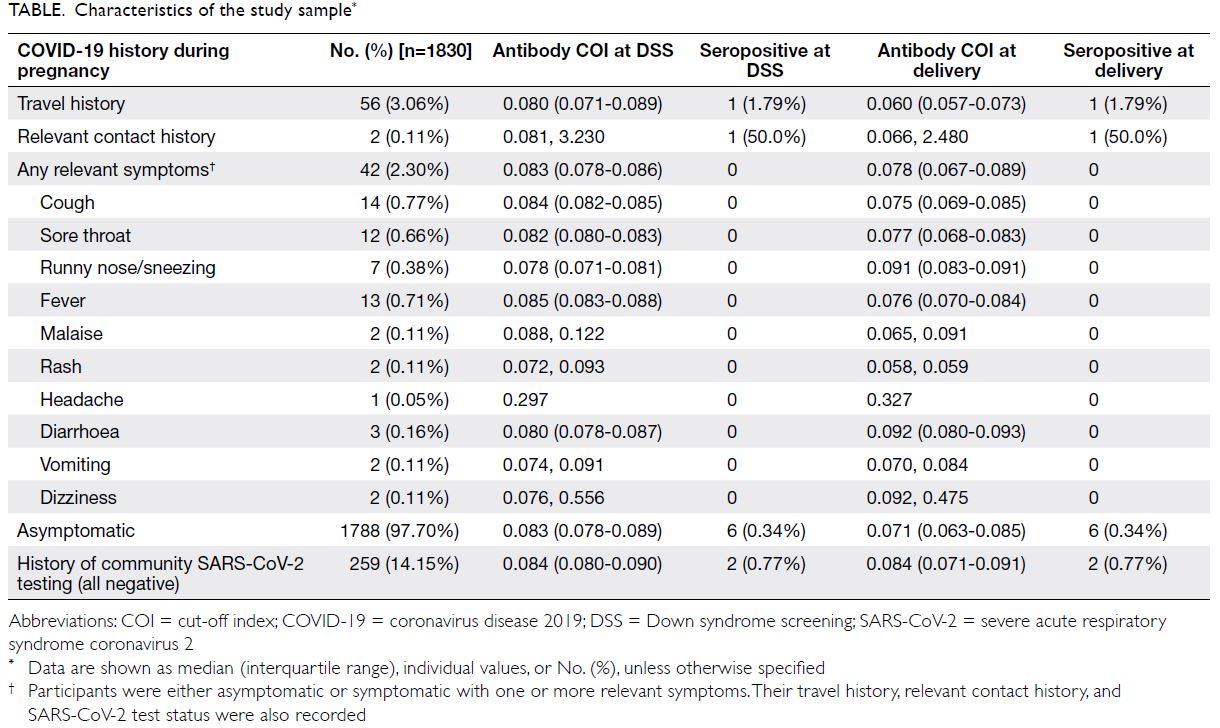

Characteristics of the study sample are

presented in the Table. Fifty six women reported a

travel history during pregnancy; one (1.79%) was

seropositive at both visits. Two women reported

relevant contact history during pregnancy; one (50.0%)

was seropositive at both visits. Forty two women

reported relevant symptoms during pregnancy;

all were seronegative at both visits. Of the 1788

asymptomatic women, six (0.34%) were seropositive

at both visits. In all, 259 women reported undergoing

community SARS-CoV-2 testing during pregnancy;

all tested negative. Among these 259 women,

two (0.77%) were seropositive at both visits.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrated a low seroprevalence

(0.33%) of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in an

unselected sample of pregnant women in Hong

Kong. Among women with risk factors for

SARS-CoV-2 infection, 1.79% and 50% with a travel

history and relevant contact history, respectively,

were seropositive. This finding suggests that targeted serological testing of pregnant women with a

positive epidemiological link is useful for identifying

women who have recovered from asymptomatic

SARS-CoV-2 infection. A limitation of this study

was that we relied on recruited individuals to recall

COVID-19 symptoms throughout pregnancy,

using only two recall time points: recruitment and

delivery. This aspect may have introduced recall bias,

particularly when COVID-19 symptoms could be

non-specific and overlap with pregnancy symptoms.

However, this limitation presumably did not have a

large effect on the results because the seroprevalence

of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody found in our

unselected sample of pregnant women was very low.

With a population of over 7 million, Hong Kong has

largely been successful in controlling the transmission

of SARS-CoV-2. Only 11 981 confirmed or probable

cases have been recorded since the beginning of the

epidemic.5 Thus, it is reasonable that the number of

asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections has also been

low; this low number of asymptomatic infections has

led to a low seroconversion rate in pregnant women.

Compared with other seroprevalence

studies in pregnant women, the seroprevalence

recorded in our study was substantially lower. The

seroprevalence rates were 14% and 21% in Barcelona6

and southern Madrid3 (both in Spain), respectively.

The low seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2

antibodies recorded in our study is presumably related to the implementation of a series of infection

control strategies, including strict border control,

mandatory quarantine for inbound travellers, mask

wearing, and meticulous contact tracing. Hong

Kong has learnt from its prior experience combating

the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)

outbreak in 2003; accordingly, it implemented

serious control measures early during the current

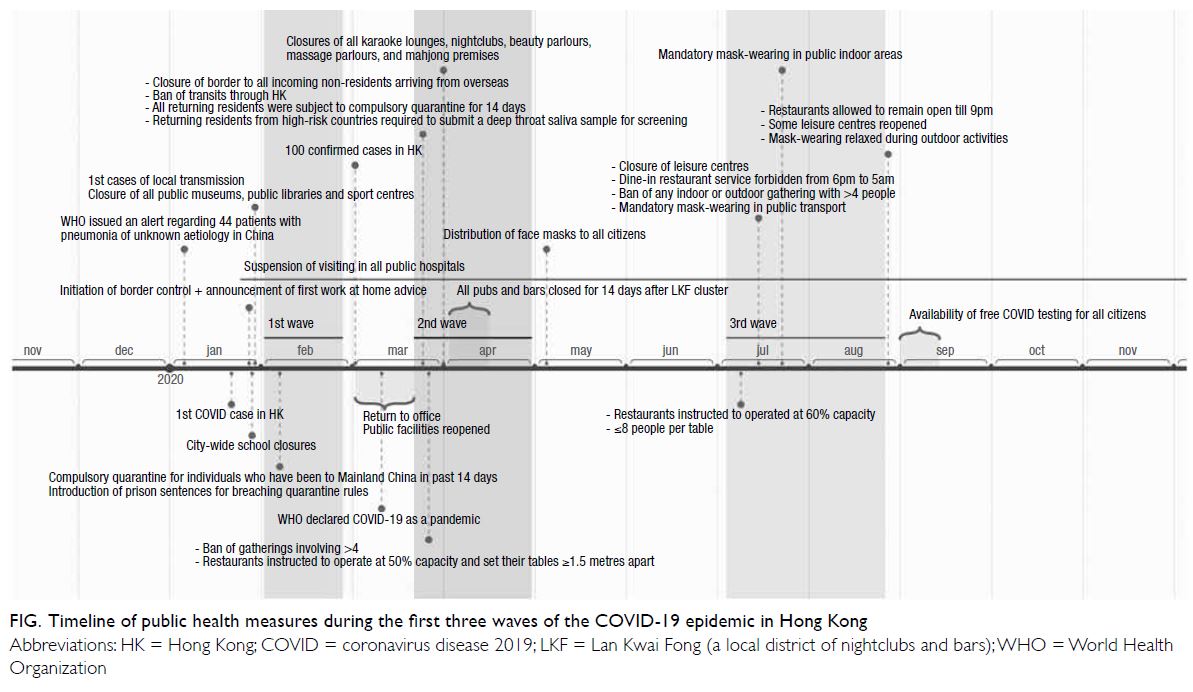

epidemic. The Figure outlines the timeline of public

health measures implemented during the first three

waves of the epidemic in Hong Kong. By the end of

March 2020, Hong Kong had closed its border to

all incoming non-residents arriving from overseas

and stopped transits through the city. All returning

residents were subject to mandatory quarantine

for 14 days; the quarantine period was extended to

21 days in December 2020. Locally, temporary

closures of gyms, karaoke venues, clubs, and

bars were periodically enforced, depending on

the incidence of COVID-19. Dine-in service was

forbidden from 6:00 pm to 5:00 am for several

months, beginning in mid-July 2020. Mask wearing

in public indoor areas and public transportation was

also mandatory at that time. Notably, all seropositive

cases in this study were first identified at the DSS

visit between February 2020 and July 2020. This

suggests that the seropositive cases acquired

their infections during the first two waves of the

epidemic; the implementation of stricter control measures by the local government during the third

wave might have led to a lower transmission rate of

asymptomatic infection among pregnant women,

resulting in a lack of seroconversion during that

period. Moreover, pregnant women are presumably

more careful about social distancing and compliant

with public health regulations. It would be useful to

compare our seroprevalence results with the findings

in other countries where strict measures were also

implemented, such as Australia and New Zealand.

Figure. Timeline of public health measures during the first three waves of the COVID-19 epidemic in Hong Kong

The humoral immune response is characterised

by the production of virus-specific neutralising

antibodies. Regardless of whether patients are

symptomatic, IgG or IgM seroconversion has

been observed in 65% to 100% of patients after

infection with SARS-CoV-2.7 8 9 10 We previously

demonstrated that 75% of pregnant women with

laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

were seropositive at delivery.11 In addition to the

strict control measures mentioned above, the low

seroprevalence recorded in our study might have

been related to undetectable antibody levels at the

time of specimen collection—the timing of blood

sample collection might not have been compatible

with antibody detection. However, this is unlikely to

have affected the findings among the large number

of pregnant women in this study. A longitudinal

study conducted in Wuhan, China, demonstrated

that the median times from the first virus-positive

test result to IgG or IgM seroconversion were 7 and

14 days in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients,

respectively.12 In the asymptomatic cohort, all

patients underwent seroconversion within 14 days

from the first positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction result.12 While waning

immunity was observed at 5 months after infection,13

two studies showed that the antibody levels remained

high and detectable at 8 months after infection.14 15

This finding is consistent with our results that the

antibodies persisted until delivery in all women who

had demonstrated seroconversion at the DSS visit.

Because the two blood samples in this study were

collected approximately 6 months apart, the timing

of specimen collection was presumably adequate to

identify most women who had contracted SARS-CoV-2 and developed detectable levels of antibodies.

Concerns regarding the usefulness of

serological testing have been raised because of the

uncertain onset and duration of humoral immunity;

our study demonstrated a very low seroconversion

yield in an unselected sample of pregnant women.

Because of the ongoing vaccination programme, it

is increasingly difficult to distinguish people who

have acquired humoral immunity through natural

infection from people who have acquired humoral

immunity through vaccination. While the strict public

health measures in Hong Kong have significantly reduced community transmission of SARS-CoV-2,

these measures cannot be maintained indefinitely.

The adverse effects of prolonged social distancing

measures on the economy, education, mental health,

and well-being of the population are immeasurable.

There is increasing evidence that the COVID-19

mRNA vaccines are safe and effective; thus,

pregnant women and women planning to become

pregnant are encouraged to undergo vaccination

at the earliest opportunity because pregnancy

is a risk factor for severe COVID-19–related

complications (eg, intensive care unit admission,

invasive ventilation requirement, and death).16 17 The

risk of preterm birth is also greater among pregnant

women with COVID-19, compared with pregnant

women who do not have COVID-19.18 19 20 Our study

has demonstrated that anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

found at DSS persist until delivery. This result

suggests that the presence of anti–SARS-CoV-2

antibodies in early pregnancy, preferably acquired

through vaccination, would provide some protection

for the pregnant woman and her baby during the

remaining portion of the pregnancy.

Until a highly effective therapeutic drug

targeting SARS-CoV-2 becomes readily available,

mass vaccination remains the best solution to control

the COVID-19 pandemic, avoid further lockdowns,

and allow a return to “normal” pre–COVID-19 life,

as well as saving lives. Our study highlights the

importance of a successful vaccination campaign.

Author contributions

Concept or design: LCY Poon, DS Sahota.

Acquisition of data: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, WC Leung, DS Sahota, MBW Leung, GCY Lui, SSS Ng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, LCY Poon.

Drafting of the manuscript: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, LCY Poon, DS Sahota.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, LCY Poon, DS Sahota, SSS Ng, PKS Chan.

Acquisition of data: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, WC Leung, DS Sahota, MBW Leung, GCY Lui, SSS Ng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, LCY Poon.

Drafting of the manuscript: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, LCY Poon, DS Sahota.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HHY Leung, CYT Kwok, LCY Poon, DS Sahota, SSS Ng, PKS Chan.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

LCY Poon has received speaker fees and consultancy payments

from Roche Diagnostics and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. She has

also received in-kind contributions from Roche Diagnostics.

Other authors have disclosed no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Lijia Chen, Tracy CY Ma, Maggie Mak, Ching-man

Mak, Angela ST Tai, Jeffery Ip, Phyllis Ngai, Andrea Chan,

and Lisa LS Chan for making substantial contributions by

involving in study coordination and patient recruitment.

Funding/support

This work was supported by Roche Diagnostic, United States,

which provided reagents for the qualitative detection of anti–

SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Ethics approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Joint Chinese

University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC Ref No. 2020.214).

Patients provided written informed consent to participate in

the study; this included consent for serum storage for research

purposes.

Trial registration

The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Ref

NCT04465474).

References

1. Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws ML,

Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic

COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission:

systematic review and meta-analysis. Off J Assoc Med

Microbiol Infect Dis Can 2020;5:223-34. Crossref

2. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, et al. Maternal and neonatal

morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with

and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID

multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:817-26. Crossref

3. Villala n C, Herraiz I, Luczkowiak J, et al. Seroprevalence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women along the

first pandemic outbreak and perinatal outcome. PLoS One

2020;15:e0243029. Crossref

4. Afshar Y, Gaw SL, Flaherman VJ, el al. Clinical presentation

of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in pregnant and

recently pregnant people. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:1117-25. Crossref

5. Hong Kong SAR Government. Together, we fight the virus!

Available from: https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/index.html. Accessed 28 Jul 2021.

6. Crovetto F, Crispi F, Llurba E, Figueras F, G mez-Roig MD, Gratac s E. Seroprevalence and presentation of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy. Lancet 2020;396:530-1. Crossref

7. W lfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological

assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019.

Nature 2020;581:465-9. Crossref

8. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease

2019. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:2027-34. Crossref

9. Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, et al. Antibody responses

to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med

2020;26:845-8. Crossref

10. Qu J, Wu C, Li X, et al. Profile of immunoglobulin G and

IgM antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:2255-8. Crossref

11. Poon LC, Leung BW, Ma T, et al. Relationship between

viral load, infection-to-delivery interval and mother-to-child

transfer of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Ultrasound

Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:974-8. Crossref

12. Jiang C, Wang Y, Hu M, et al. Antibody seroconversion

in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients infected

with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2). Clin Transl Immunology 2020;9:e1182. Crossref

13. Choe PG, Kang CK, Suh HJ, et al. Waning antibody

responses in asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2

infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:327-9. Crossref

14. Hartley GE, Edwards ES, Aui PM, et al. Rapid generation

of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and

nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence.

Sci Immunol 2020;5:eabf8891. Crossref

15. Choe PG, Kim KH, Kang CK, et al. Antibody responses 8 months after asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:928-31. Crossref

16. UK Government. JCVI issues new advice on COVID-19

vaccination for pregnant women. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/jcvi-issues-new-advice-on-covid-19-vaccination-for-pregnant-women. Accessed

17 May 2021.

17. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

HKCOG advice on Covid-19 vaccination in pregnant and

lactating women (interim; updated on 21 April 2021).

Available from: https://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Upload/EditorImage/20210423/20210423141055_6024.pdf.

Accessed 17 May 2021.

18. Martinez-Portilla RJ, Smith ER, He S, et al. Young pregnant

women are also at an increased risk of mortality and

severe illness due to coronavirus disease 2019: analysis of

the Mexican National Surveillance Program. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2021;224:404-7. Crossref

19. Martinez-Portilla R, Sotiriadis A, Chatzakis C, et al.

Pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection are at higher

risk of death and pneumonia: propensity score matched

analysis of a nationwide prospective cohort (COV19Mx).

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:224-31. Crossref

20. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations,

risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of

coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:e3320. Crossref