© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Pioneering female doctors of The University

of Hong Kong

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)

Member of the Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

The first female doctor of Hong Kong was Dr Alice Hickling (nee Sibree) who arrived in 1904 to work

at the Alice Memorial Maternity Hospital. She was

a pioneer in the training of local midwives with

modern Western methods of childbirth.1 It would

take another two decades for the emergence of local

female doctors.

When The University of Hong Kong (HKU)

was established in 1911, the Hong Kong College of

Medicine was merged with HKU and became the

Medical Faculty. During the next decade, no female

students were admitted to HKU. In 1921, Rachel

Irving—daughter of the Director of Education,

Edward Irving—applied for admission and was

refused. When Mr Irving sought legal advice, HKU

backed down as there was no legal basis for barring

female students. In that year, three female students—Rachel Irving, Irene Hotung, and Po-chuen Lai—were granted admission. Lai became the very first

female medical student of the Medical Faculty. In

1927, Eva Hotung, elder sister of Irene, who was

admitted in the spring term of 1922, became the first female graduate of the Medical Faculty.2 This

photograph was taken in 1926 during their surgical

clerkship at the Government Civil Hospital in Sai

Ying Pun (Fig).

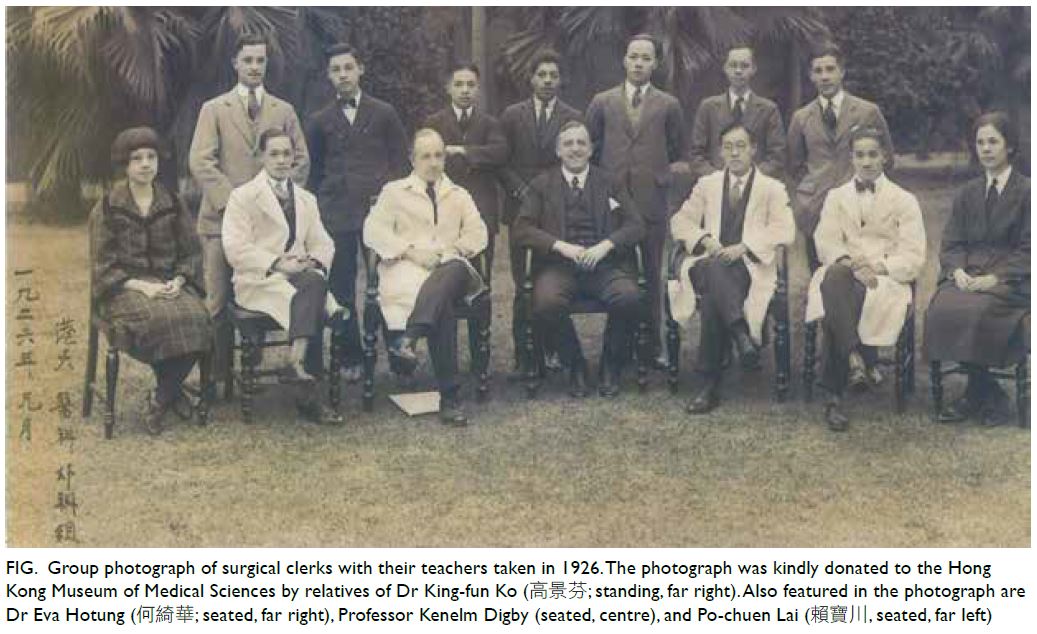

Figure. Group photograph of surgical clerks with their teachers taken in 1926. The photograph was kindly donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by relatives of Dr King-fun Ko (高景芬; standing, far right). Also featured in the photograph are Dr Eva Hotung (何綺華; seated, far right), Professor Kenelm Digby (seated, centre), and Po-chuen Lai (賴寶川, seated, far left)

Dr Eva Hotung (何綺華) was the daughter

of Sir Robert Hotung, a successful businessman

and philanthropist. She attended Diocesan Girls’

School and passed the Senior Local Examination

(matriculation examination at HKU) in 1918, but

had to wait for 4 years for her chance to study

medicine in HKU. She proved to be a bright student

and was awarded both the Ng Li Hing and Chan

Kai Ming scholarships for the subjects of anatomy

and physiology during the third-year examinations.

She was also the only candidate who passed all the

subjects in one sitting at her final MBBS examination

in December 1926.3 After graduation she moved to

Europe for further studies and earned diplomas

in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in London, and

in Gynaecology and Obstetrics in Dublin. She

was also the first Chinese to obtain the MRCP

(Ireland) qualification, demonstrating again her academic prowess. She returned to Hong Kong

in the early 1930s and joined the HKU Obstetrics

and Gynaecology Department. Eventually, she was

promoted to First Assistant to the Professor of the

Department in 1937. This was probably the highest

rank a local Chinese doctor could achieve in those

days. At this juncture, the Sino-Japanese war steered

her path away from Hong Kong. In 1938, she joined

the Medical Relief Corps of the Chinese Red Cross

and commanded a field unit to provide medical

care and to perform anti-epidemic work.4 After the

war, she started her own practice in obstetrics and

gynaecology in the Central district of Hong Kong.

Her practice was highly successful but the years of

hard work took a toll on her health. She decided to

close her practice and move to New York in 1960.

She died in New York in 1993 at age 90 years.

Dr Po-chuen Lai (賴寶川) came from an

ordinary family, her father being a storekeeper of

the public works department. After graduating from

the Italian Convent School (Sacred Heart Canossa

College today), she made history as the first female

medical student of HKU. Lai was not as brilliant as

Hotung, and graduated 1 year after her in 1928.5 She

joined the civil service as Chinese Medical Officer

on 1 June 1928 and worked in Tsan Yuk Hospital

until 1933. She was assistant to Dr Alice Hickling,

who was then Assistant Medical Officer in charge of

Chinese Hospitals and Chinese Public Dispensaries.

In 1939, after a decade in the civil service, Lai was

appointed Secretary to the Midwives Board and

Supervisor of Midwives and simultaneously Health

Officer and Inspector of Schools. During the

Japanese occupation, Lai remained in Hong Kong

to help the humanitarian work of Dr Selwyn-Clarke.

Dr Selwyn-Clarke, who was Director of the Medical

Department, was organising a network to help the

dependents of internees or servicemen who died

during the war and supplying necessary drugs and

food items to the camps. He was arrested in 1943

by the Japanese Kempeitai for espionage and Lai

continued the work in his absence. For her invaluable

work during the war time, she was awarded OBE in

1946. Lai resumed duty immediately after the war

and was put in charge of both the Infant Welfare Centres and the School Health Program. In 1947,

Lai was promoted to Lady Medical Officer, a post

previously only for “Europeans” but opened by then

to local Chinese. In 1949, Lai left government service

for private practice.6

Also in the photograph are Professor Kenelm

Digby, founding chair of the Department of

Surgery, and Dr King-fun Ko (高景芬) , owner of

the photograph. Digby joined the infant Medical

Faculty in 1913 as Professor of Anatomy and

became its Dean in 1915. At that time there was

no full-time professors in the clinical departments.

Professors in Medicine, Surgery and Obstetrics and

Gynaecology were created in the early 1920s with

endowment from the Rockefeller Foundation. He

laid the foundation of surgical education in Hong

Kong during his long reign before the War. He was

held in Stanley Internment Camp during Japanese

Occupation where he continued to operate in the

Tweed Bay Hospital inside the camp. He resigned

from HKU soon after liberation due to ill health.

The Department of Surgery of HKU has created the

Digby Memorial Lecture in his honour.7 Ko did not

enter HKU after graduating from Queens College.

He went to Tianjin to study medicine at the Pei Yang

Medical College, which was established by Li Hong

Zhang during the Qing Dynasty. He came back to

Hong Kong after 1925 to enrol into the Medical

Faculty. Ko graduated in 1928 and joined Tung Wah

Hospital as a resident doctor for 3 years. He then

went into private practice and joined the group

practice of Dr Mak Luk.

Hotung, Lai, and other early female doctors trod a more difficult path than their male counterparts.

For example, within the civil service, woman medical

officers’ salaries were only about 75% that of men until

the 1970s. They were also more likely to be posted

in traditional “female” disciplines (eg, obstetrics or

child health) and were less likely to gain promotion.

In the colonial days, racial discrimination was also

reflected in differences in pay between local and

European staff. Fortunately, these days the sexes are

equally represented at the medical schools in Hong

Kong and there are equal opportunities in the choice

of specialties.

References

1. George J. The Lady Doctor’s ‘Warm welcome’: Dr Alice Sibree and the early years of Hong Kong’s maternity service 1903-1909. J Hong Kong Branch R Asiat Soc 1993;33:81-109.

2. Cheng I. Intercultural Reminiscences. David C Lam Institute for East-West Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University; 1997.

3. Student card of Eva Ho Tung. University Archives, The University of Hong Kong.

4. Ride L. The test of War. In: Matthews C, Cheung O, editors. Dispersal and Renewal: Hong Kong University during the War Years. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 1998: 12.

5. Student card of Lai Po Chuen. University Archives, The University of Hong Kong.

6. The Hong Kong Civil Service List for 1949, Government Printers.

7. Chan J, Patil NG. Digby: a Remarkable Life. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2006.