© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Primary pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid

tissue lymphoma with radiological presentation of middle lobe syndrome diagnosed by bronchoscopy: a case report

H Zhou, MD1; Z Yang, MD2; S Wu, MD1

1 Cancer Center, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital (Affiliated People’s Hospital, Hangzhou Medical College), PR China

2 Cancer Center, Department of Pathology, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital (Affiliated People’s Hospital, Hangzhou Medical College), PR China

Corresponding author: Dr S Wu (wushengchang@126.com)

Case report

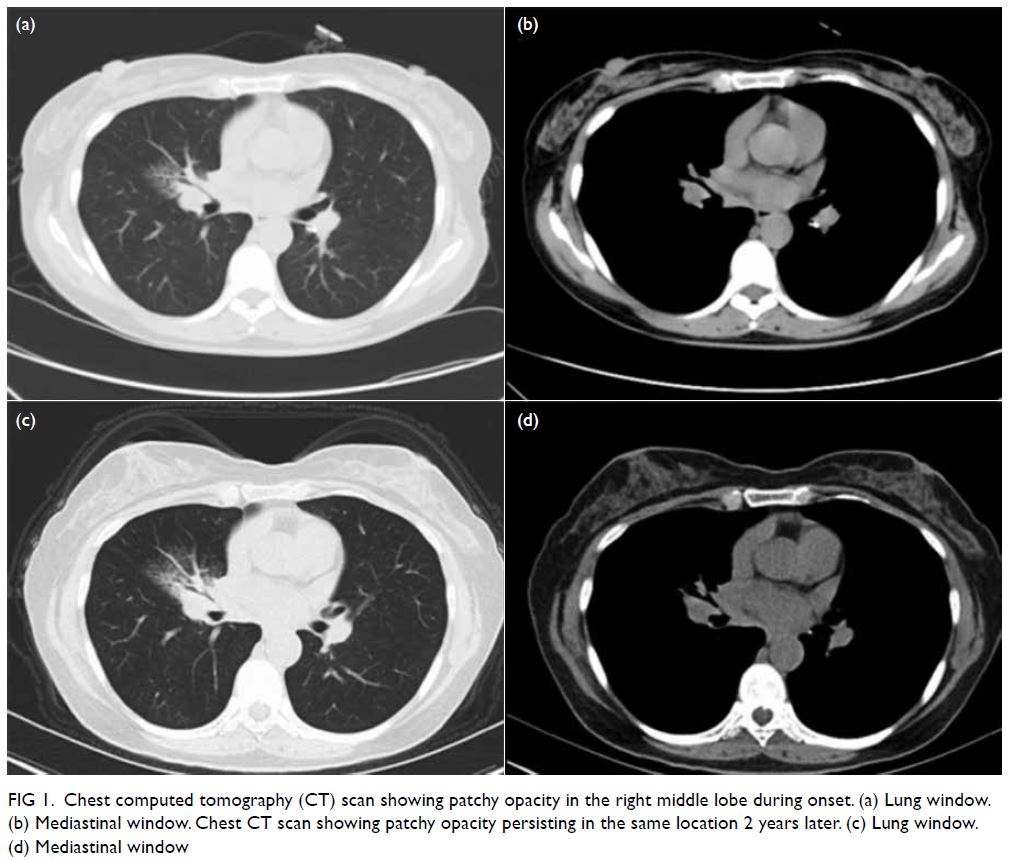

In March 2018, a 49-year-old woman was admitted to

our respiratory medicine ward with a 2-year history

of recurrent productive cough. Symptoms first

developed after the patient underwent laparoscopic

myomectomy and subsequently developed a fever (around 38°C). Chest computed tomography (CT)

revealed patchy opacity in the right middle lobe

(Fig 1a and b). Based on these symptoms, she was

diagnosed with “pneumonia” for which antibiotics

were prescribed. Her fever resolved but cough

persisted so she was prescribed cough suppressants and antibiotics intermittently. These therapies were

likewise ineffective.

Figure 1. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan showing patchy opacity in the right middle lobe during onset. (a) Lung window. (b) Mediastinal window. Chest CT scan showing patchy opacity persisting in the same location 2 years later. (c) Lung window. (d) Mediastinal window

A series of tests and examinations conducted

during hospitalisation revealed no definitive cause

and symptoms again persisted. A new chest CT scan

revealed no change to the right middle lobe opacity

compared with previous CT scan and stenosis of the

middle bronchus (Fig 1c and d).

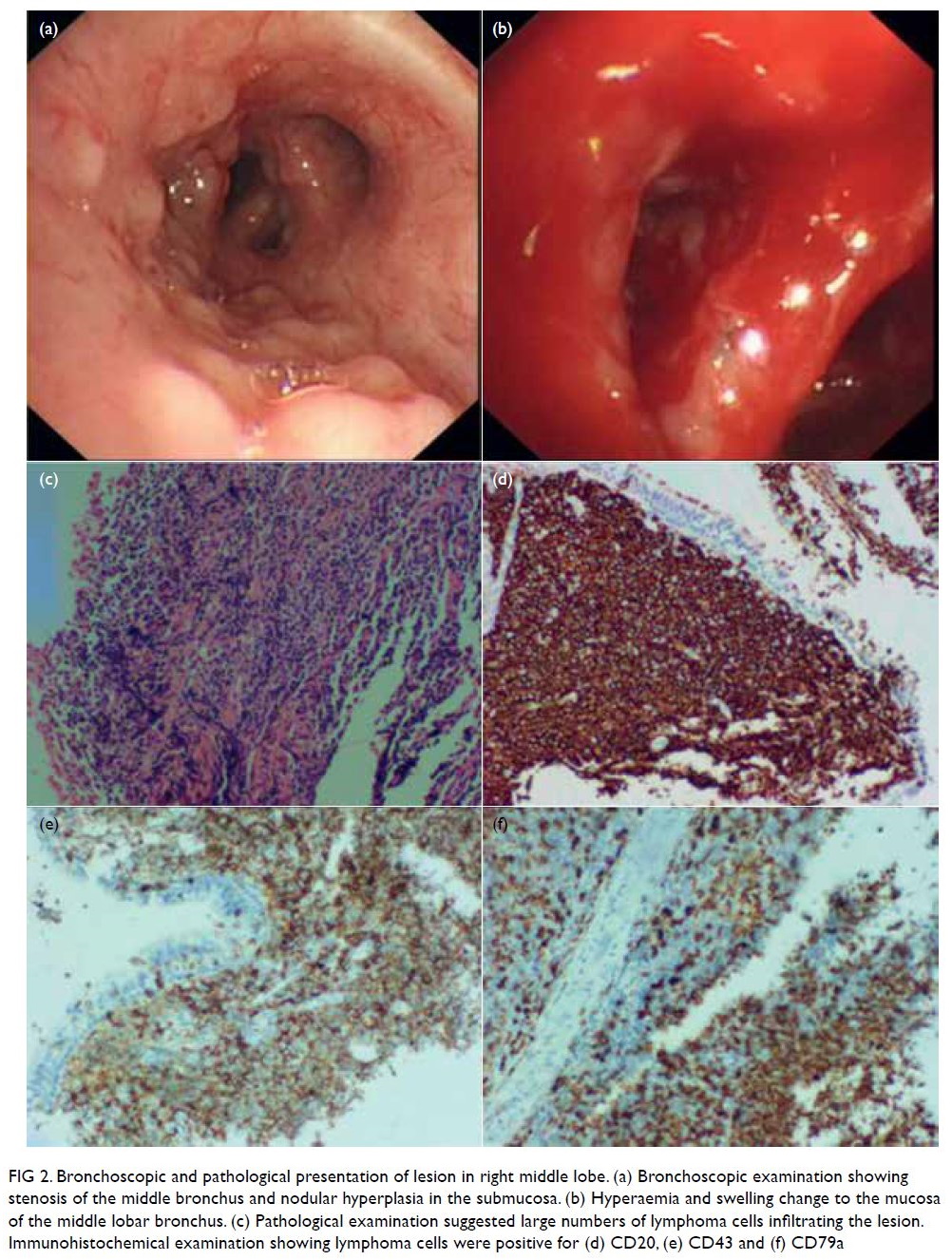

In the absence of any treatment response, the

patient was advised to undergo bronchoscopy that

revealed a narrowed lumen and rough mucosa of

the middle bronchus. Pathological examination

of mucosal tissue biopsy from the lesion revealed

infiltration of large numbers of lymphocytes

(Fig 2a and b) suggestive of diagnosis of lymphoma.

Further immunohistochemistry examination confirmed that the lesion was caused by mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

These lymphoma cells tested positive for CD20,

CD79a and CD43 (Fig 2c-f). Further examinations

including positron emission tomography–computed

tomography and gastroscopy revealed no evidence

of lymphoma elsewhere.

Figure 2. Bronchoscopic and pathological presentation of lesion in right middle lobe. (a) Bronchoscopic examination showing stenosis of the middle bronchus and nodular hyperplasia in the submucosa. (b) Hyperaemia and swelling change to the mucosa of the middle lobar bronchus. (c) Pathological examination suggested large numbers of lymphoma cells infiltrating the lesion. Immunohistochemical examination showing lymphoma cells were positive for (d) CD20, (e) CD43 and (f) CD79a

The patient underwent radiotherapy about

6 months after final diagnosis, with a total dose of

3960 cGy. After the last radiotherapy treatment,

chest CT confirmed that the lesion in the right

middle lobe had nearly disappeared. In addition,

symptoms of cough and expectoration had improved

significantly. The patient was followed up once every

3 months. Chest CT scan at the most recent follow-up

examination indicated no sign of relapse and her

symptoms had resolved.

Discussion

Primary pulmonary lymphoma belongs to a group of lymphoproliferative diseases, and accounts for 0.5%

to 1% of all pulmonary tumours.1 Mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue lymphoma is the most common

pathological type of primary pulmonary lymphoma.2

However, the disease may not be diagnosed until

pathological examinations are conducted due to a

lack of clinical and radiological characteristics.

Previous study suggests that about half of patients with MALT lymphoma are asymptomatic

and some are diagnosed by accident.3 In patients

with symptoms, respiratory symptoms are more

frequently observed than B symptoms, including

fever, fatigue and weight loss.3 Our patient presented

with a transient B symptom of fever, but a chronic

respiratory symptom of cough.

The radiological presentation of this disease is diverse and includes nodules, masses, consolidation

and group glass opacity. Multiple lesions, which

are often bilaterally distributed, can be detected

by CT scan in most cases, but a solitary lesion is

less common in patients with MALT lymphoma.4

In addition, MALT lesions may occur in any lung

lobe or large airway including the trachea and main

bronchus.4 5 In our patient, the right middle lobe was affected, and middle lobe syndrome (MLS) was the

major radiological feature.

Middle lobe syndrome was first mentioned

several decades ago by Graham6 to describe

atelectasis of the right middle lobe. The syndrome is

usually caused by extrinsic compression or intrinsic

stricture of the middle lobe bronchus.6 However,

there is no uniform definition of this term. Broadly

speaking, MLS is defined as damage to the right

middle lobe due to any cause. The most common

causes are bronchiectasis, non-specific inflammation,

tuberculosis and tumours. Lung cancer is the most

common type of tumour affecting the middle lobe. As a haematological disease, MALT lymphoma can

affect any organ or tissue although in our patient, it

affected only the right middle lobe with consequent

misdiagnosis for more than 2 years. It is particularly

rare for MALT lymphoma to present as MLS. Only

one similar case has been reported: in 2004, Toishi

et al7 reported a 70-year-old male patient with a

radiological change of MLS who was diagnosed with

MALT lymphoma by right middle lobectomy. In

our case, the final diagnosis was obtained by biopsy

during bronchoscopy, not surgery.

Given that the clinical and radiological

features of MALT are non-specific, its definitive

diagnosis relies on pathology. Diffuse infiltration of

small lymphocytes into the bronchiolar mucosa is a

major histological characteristic. Moreover, reactive

lymphoid follicles and lymphoepithelial lesions are

commonly observed by microscopy.4 The molecular

markers of MALT are CD20, CD79a, CD43, as

observed in our case. CD5, CD10 and cyclin D are

always negative and may help to discriminate other

types of lymphoma. It was difficult to distinguish

this disease from infectious diseases and benign

lymphoproliferative diseases in the absence of

pathological examination.

Generally, MALT lymphoma is a tumour of

low-grade malignancy and patients have a rather good

prognosis. The 5-year survival rate for patients with

MALT lymphoma is >80%.4 The main treatments

for the disease are chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

target therapy and immunotherapy. Radiotherapy

is the first choice in patients with localised lesions.

It has been estimated that >90% of patients can

achieve a complete response after radiotherapy.8

Surgery may be indicated when the lesion is isolated

in certain organs, such as lung, thyroid gland, and

spleen. However, if MALT lymphoma progresses to

an advanced stage, or patients have a high tumour

burden, systemic therapy is recommended. Anti-CD20 combined with chemotherapy is considered

first-line treatment.7 In the present case, the patient

refused chemotherapy and agreed to radiotherapy

that relieved her symptoms with no obvious adverse

effects.

In summary, we first report MALT lymphoma

as a rare cause of MLS that was confirmed using a

minimally invasive approach. Mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue lymphoma should be considered

a differential diagnosis when investigating the

aetiology of MLS.

Author contributions

Concept or design: H Zhou, S Wu.

Acquisition of data: Z Yang, S Wu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: H Zhou, Z Yang.

Drafting of the manuscript: H Zhou, S Wu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: Z Yang, S Wu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: H Zhou, Z Yang.

Drafting of the manuscript: H Zhou, S Wu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent for all treatment and procedures and for publication of this

paper.

References

1. Cardenas-Garcia J, Talwar A, Shah R, Fein A. Update in primary pulmonary lymphomas. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21:333-7. Crossref

2. Borie R, Wislez M, Antoine M, Copie-Bergman C, Thieblemont C, Cadranel J. Pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma revisited. Eur Respir J

2016;47:1244-60. Crossref

3. Zhang MC, Zhou M, Song Q, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of pulmonary lymphoma: a single center

experience of 180 cases. Lung Cancer 2019;132:39-44. Crossref

4. Sirajuddin A, Raparia K, Lewis VA, et al. Primary

pulmonary lymphoid lesions: radiologic and pathologic

findings. Radiographics 2016;36:53-70. Crossref

5. Kawaguchi T, Himeji D, Kawano N, Shimao Y, Marutsuka K.

Endobronchial mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

lymphoma: a report of two cases and a review of the

literature. Intern Med 2018;57:2233-6. Crossref

6. Graham EA, Burford TH, Mayer JH. Middle lobe syndrome. Postgrad Med 1948;4:29-34. Crossref

7. Toishi M, Miyazawa M, Takahashi K, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; report of two cases [in Japanese]. Kyobu Geka 2004;57:75-9.

8. Lumish M, Falchi L, Imber BS, Scordo M, von Keudell G, Joffe E. How we treat mature B-cell neoplasms (indolent B-cell lymphomas). J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:5. Crossref