Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):133–9 | Epub 12 Apr 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Patient acceptance of transvaginal sonographic

endometrial thickness assessment compared

with hysteroscopy and biopsy for exclusion of

endometrial cancer in cases of postmenopausal

bleeding

Linda WY Fung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Eva CW Cheung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FRCOG; Alyssa SW Wong, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FRCOG; Daljit S Sahota, PhD; Terence TH Lao, MD, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Linda WY Fung (lindafung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Available examinations for women

with postmenopausal bleeding include transvaginal

sonography to measure endometrial thickness

(TVS-ET), and invasive endometrial assessment

using hysteroscopy/endometrial biopsy. However,

selection of the examination method seldom

involves consideration of patient preferences. The

aim of this study was to examine patient preferences

for the method used to investigate postmenopausal

bleeding.

Methods: Women were asked to complete an

interviewer-administered structured survey before

they underwent clinical investigations at a university

gynaecology unit from June 2016 to June 2017.

Using the standard gamble approach, women were

asked to choose between invasive assessment by

hysteroscopy/endometrial biopsy (gold standard)

or TVS-ET with a risk of missing endometrial

cancer. The risk of missing endometrial cancer

during TVS-ET was varied until each woman was

indifferent to either option.

Results: The median detection rate for endometrial

cancer required using TVS-ET was 95% (interquartile

range=80%-99.9%). In total, 200 women completed

the survey, and 77 (38.5%) women required TVS-ET to have a 99.9% detection rate for endometrial

cancer. Prior hysteroscopy experience was the only

factor that influenced the women’s decisions: a

significantly higher detection rate was required by

this patient group than by patients without previous

hysteroscopy experience (P=0.047).

Conclusions: A substantial proportion of women

would accept TVS-ET alone for the investigation

of postmenopausal bleeding. In the era of patientcentred

care, clinicians should incorporate

patient preferences and enable women to make

informed choices concerning the management of

postmenopausal bleeding.

New knowledge added by this study

- We assessed patient preferences for the investigational approach used to exclude endometrial cancer in Hong Kong women with postmenopausal bleeding.

- In our study population, most women would select transvaginal sonography to measure endometrial thickness (TVS-ET) if the endometrial cancer detection rate were >95%; if the TVS-ET detection rate were ≤95%, the women would select the more invasive hysteroscopy/endometrial biopsy approach.

- Nearly 40% of the women required TVS-ET to detect nearly all endometrial cancers before they would select TVS-ET as the sole investigational approach.

- Using an endometrial thickness cut-off value of 3 mm, a substantial proportion of women would accept TVS-ET alone for the investigation of postmenopausal bleeding.

- Women with previous hysteroscopy experience prefer hysteroscopic assessment unless TVS-ET alone can achieve a nearly identical rate of endometrial cancer detection.

- Clinicians should incorporate patient preferences concerning the investigation of postmenopausal bleeding to enable an informed choice about invasive testing to exclude endometrial cancer.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is among the most common

gynaecological malignancies worldwide. Among

women with endometrial cancer, 90% initially report

postmenopausal bleeding (PMB).1 2 3 4 5 Approximately

10% of postmenopausal women are estimated to

experience PMB.1 Generally, there is no harmful

underlying cause of PMB; however, women with

recurrent PMB require medical assessment

to distinguish between benign aetiology (eg,

vaginal atrophy, uterine fibroids, and polyps) and

endometrial cancer. Endometrial assessment is

needed to exclude underlying malignancy.2 6 7 8 9 10

The endometrium can be examined non-invasively,

using transvaginal sonography (TVS)

to measure endometrial thickness (TVS-ET);

alternatively, it can be examined invasively via

blinded undirected endometrial sampling, saline

infusion sonography, or diagnostic hysteroscopy.11 12 13

Although both TVS-ET and blinded endometrial

sampling are recommended as first-line

investigations,2 6 7 14 15 16 17 18 the gold standard approach for

PMB investigation remains diagnostic hysteroscopy

with visually guided endometrial sampling; this

allows direct visualisation of the uterine cavity and

histological investigation.19

Importantly, hysteroscopy is invasive and

carries risks of complications such as infection, bleeding, uterine perforation, and visceral injury to

the cervix or nearby organs (eg, bladder and bowel);

it cannot be performed in women with cervical

stenosis.20 Additionally, some women report that

hysteroscopy is uncomfortable and painful within

an out-patient or office setting; thus, hysteroscopy,

cervical dilation, and uterine curettage have been

performed under general anaesthesia in such cases.

Although TVS-ET has become an established

investigational tool, there remains a lack of

consensus concerning the endometrial thickness (3,

4, or 5 mm) that constitutes ‘abnormal’. Our previous

study of 4300 women with PMB demonstrated that

3% of women with PMB and endometrial thickness

≤3 mm had endometrial cancer.21

Patient preference regarding investigation

approach is an important component of the decision

care pathway. Individual women must balance the

risks associated with an invasive procedure (eg,

diagnostic hysteroscopy) with the risk of missing an

endometrial cancer diagnosis if they select a non-invasive

assessment (eg, TVS-ET). To our knowledge,

the nature of this balance has not been assessed. The

aim of the present study was to determine the extent

to which women with PMB would accept the risk of

missing endometrial cancer if they were to undergo

TVS-ET as the first investigation of PMB.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in a

tertiary centre in Hong Kong from June 2016 to

June 2017. Women referred by either primary

or secondary healthcare providers to the One-stop

PMB Clinic for assessment and management

were invited to participate in the study. Patient

assessments included history taking, physical

examination, pelvic ultrasound to measure

endometrial thickness and screen for other pelvic

pathologies, Pap smear (for women without recent

Pap smear records), endometrial sampling with

or without hysteroscopy. Women were excluded if

they had <1 year of amenorrhea; had a prior TVS

finding of endometrium thickness ≥5 mm; were aged

≥70 years; had dementia or mental retardation;

and/or were unable to read or understand Chinese.

Prior to their clinic consultation, study

participants completed a structured interview that

was administered by an independent interviewer.

Women were asked to first read an information

leaflet regarding PMB, which described the risk of

endometrial cancer, possible investigation options,

and the risks associated with each option. The leaflet

and interviewer explained that hysteroscopy and

endometrial biopsy were expected to achieve a 100%

detection rate, but these methods involved risks of

pain, bleeding, infection, and uterine perforation

related to uterine cavity exploration. The leaflet and

interviewer also explained that TVS-ET did not require entry into uterine cavity but would potentially

miss some cases of endometrial cancer. The leaflet

and interviewer did not disclose the percentage of

endometrial cancers that would fail to be detected by

TVS-ET. After they had read the leaflet, women were

asked to complete a study questionnaire regarding

their sociodemographic characteristics and their

personal and family histories of gynaecological

cancer; they also completed the Chinese version of

the 20-item State-Trait Anxiety Inventory to measure

their trait and state anxiety levels. The women’s

state and trait scores were categorised as above or

below the scale midpoint. Women then underwent

assessment of utilities regarding examination by

either hysteroscopy or TVS-ET and the possibility

of a missed cancer diagnosis, using the standard

gamble technique.22

The standard gamble technique is the gold

standard method used to determine utility towards

a particular health state when a risk is involved.

Individuals are asked to choose whether they prefer

to have a certain guaranteed option or health state

with a guaranteed outcome and no risk, or whether

they would prefer an alternative option which entails

some risk. The risks for the two health states are

varied until the individual becomes indifferent to

either option. At the point of indifference, the ‘utility’

for the health state under consideration is considered

equal to ‘p’, while the utility of the alternative health

state is considered equal to ‘1–p’.

Women were first asked to complete a standard

gamble related to blindness, thereby ensuring that

they understood the process. Subsequently, they were

asked to complete a standard gamble to test their

preferences towards the investigations of PMB. Each

woman was asked to choose between the following

tests: (1) TVS-ET, which is less invasive but involves

some risk of missing endometrial cancer (probability

of 1–p), or (2) an invasive test with hysteroscopy

and endometrial biopsy, which detects 100% of all

cancers but carries the risks described during the

structured interview. To determine the level of

acceptance of missing endometrial cancer during

TVS-ET, the women were initially informed that the

assumed detection rate of the TVS-ET was 75%; this

detection rate was then increased in 5% intervals to

90%, then in 1% intervals to 98%, and finally in 0.1%

intervals to 99.9%. We recorded the stated detection

rate at which the woman was indifferent to either

option. The missed endometrial cancer rate that

women would accept to avoid an invasive procedure

was defined as 1–detection rate.

Sociodemographic characteristics, past and

current gynaecological history findings, and anxiety

levels are presented as mean ± standard deviation or

median and interquartile range; qualitative variables

are presented as absolute frequency and percentage.

The acceptable rate of endometrial cancer detection by TVS-ET alone, as an alternative to invasive

hysteroscopy/biopsy, is presented as median and

interquartile range. Differences in scores among

sociodemographic groups were compared using the

Mann-Whitney U test. SPSS software (Windows

version 20; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States)

was used for all statistical analyses. A P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

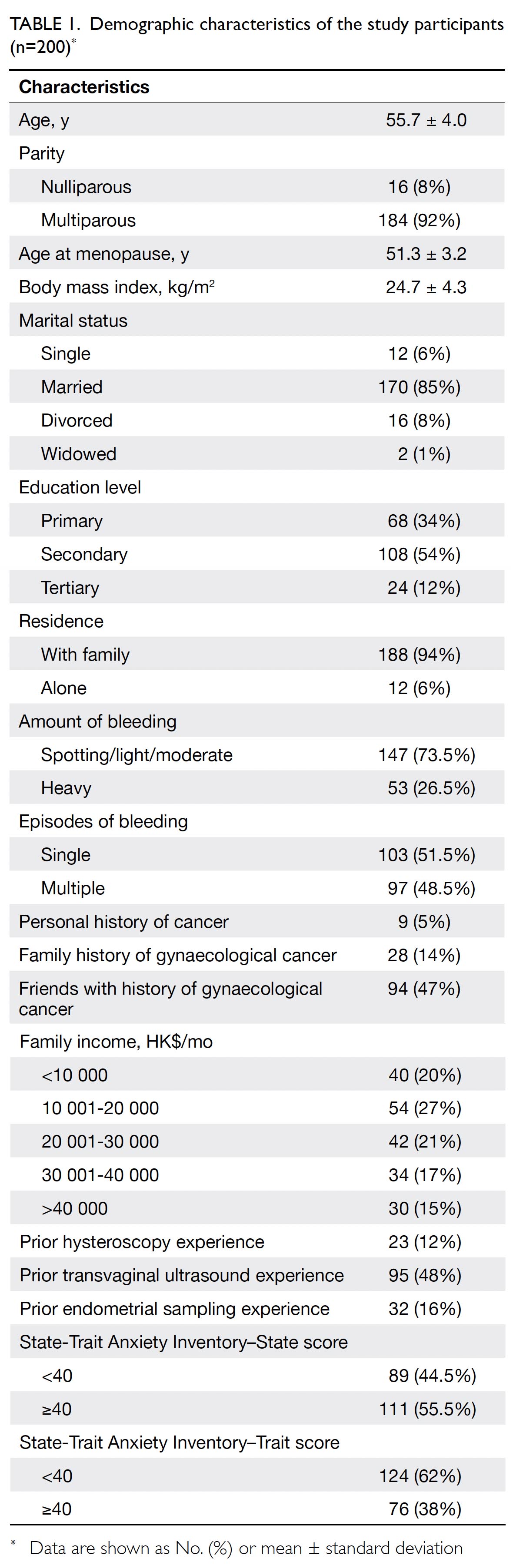

During the study period, 202 women agreed to

participate in the study; 200 of these women

completed the questionnaires and the standard

gamble assessments. Table 1 summarises the

sociodemographic, obstetric and gynaecological

histories, and anxiety levels of these 200 women.

Overall, 11 (5.5%) of the 200 women were

subsequently diagnosed with cancer or an atypical

endometrium: nine had endometrial cancer, one had

cervical cancer, and one had atypical hyperplasia.

Among 42 patients who underwent Pap smears in

our clinic, smear results showed atypical glandular

cells in two patients with endometrial cancer, while

four patients with endometrial cancer had a shift in

vaginal flora suggestive of bacterial vaginosis; the

remaining smear results were normal.

The median endometrial cancer detection rate

or utility that women would require for selection of

TVS-ET to avoid invasive hysteroscopy examination

was 95% (interquartile range=80%-99.9%). Overall,

77 (38.5%) women required TVS-ET to have a 99.9%

detection rate for endometrial cancer. Thus, 38.5% of

the women in our cohort would require TVS-ET to

be comparable with diagnostic hysteroscopy before

they would accept TVS-ET as the sole method for

examination of the endometrium and uterine cavity.

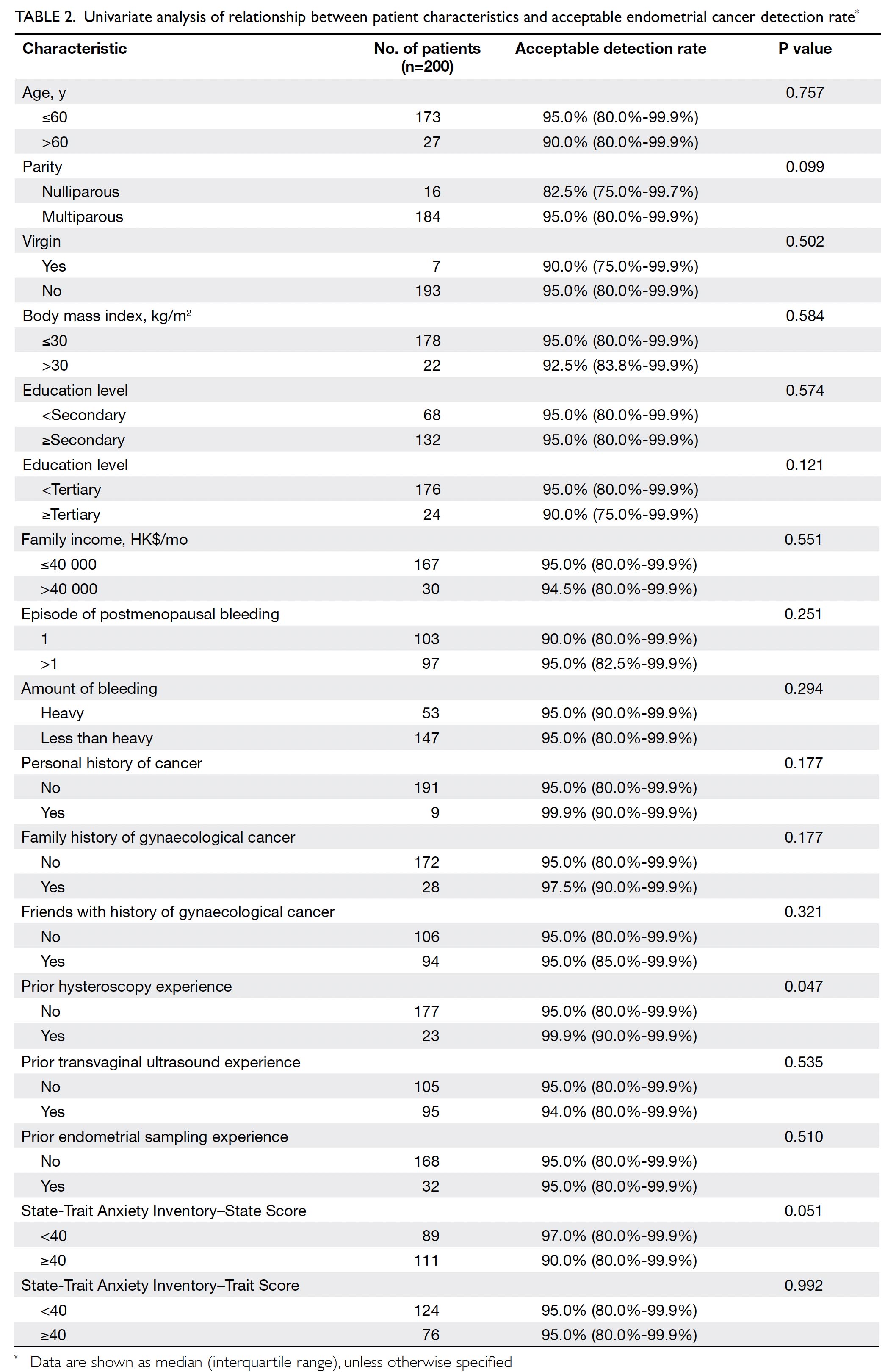

Table 2 summarises the results of univariate

analysis of the relationships between patient

characteristics and the TVS-ET endometrial cancer

detection rate. Women with previous hysteroscopy

experience required the endometrial detection rate

by TVS-ET to be significantly higher than did women

without previous hysteroscopy experience (P=0.047).

There were no significant differences in required

endometrial cancer detection rates by TVS-ET

among other sociodemographic characteristics, past

and current obstetric and gynaecological histories,

and state or trait anxiety (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate analysis of relationship between patient characteristics and acceptable endometrial cancer detection rate

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to utilise

the standard gamble technique to evaluate patient

preference with regard to approaches used for the

investigation of PMB. Specifically, we assessed the

extent to which women would prefer to avoid an

invasive investigation (eg, hysteroscopy and biopsy)

if a non-invasive alternative were available. Our findings suggested that TVS-ET would need to

detect approximately 95% of endometrial cancers

(or miss approximately 5% of endometrial cancers)

for women to select TVS-ET with the intention

of avoiding an invasive investigation. However,

our analysis also suggested that nearly 40% of the

participants required TVS-ET to detect nearly

all endometrial cancers before they would select

TVS-ET as the sole investigational approach.

There are sparse published data concerning

patient preferences for the investigation of PMB.

Our literature review revealed a single study by

Timmermans et al.23 However, that study was

limited to 39 participants and the results were

obtained via telephone survey. In contrast to our

protocol, Timmermans et al23 only assessed patient

preferences after the women’s investigations had

been completed; thus, their reported clinical

experiences and preferences might have been

biased. In the present study, we adopted the

standard gambling approach which enabled a more

quantitative analysis of patient willingness to select

a different investigational approach. The standard

gamble method is the gold standard approach for

assessment of preferences in an uncertain situation24;

it can be used to express the outcomes of different

choices. It has been used previously to explore the

acceptable risk of miscarriage after a high-risk Down

syndrome screening test25 26 27 28; it has also been used to

explore patient preferences concerning the risks of

other medical treatments.

Currently, endometrial thickness cut-off

values in endometrial pathology or cancer screening

differ among hospitals.2 6 19 The most commonly

used cut-off endometrial thickness value is 4 mm2.

Our study population of postmenopausal women

accepted an endometrial cancer detection rate of

95% when using TVS-ET alone, with the intention

of avoiding the more invasive procedure of

hysteroscopy/endometrial biopsy. In our previous

study, TVS-ET offered endometrial cancer detection

rates of 97%, 94.1%, and 93.5% using 3 mm, 4 mm, and

5 mm as respective cut-off values.21 Thus, a TVS-ET

cut-off of 3 mm would generally be consistent with

the endometrial cancer detection accuracy that

women in our study required for TVS-ET to be used

as the sole investigational approach. In our study

population, women with previous hysteroscopy

experience required TVS-ET to have higher

detection rates; hence, they preferred hysteroscopic

assessment.

There were some limitations in our study.

First, women aged ≥70 years were excluded because

we presumed that they would have difficulty

understanding the standard gamble technique and/or completing the study questionnaires without

assistance. Second, although our sample size

was sufficient to assess our primary goal, it was inadequate for subgroup analysis. Larger studies

are needed to explore the relationships of specific

patient characteristics with the acceptable rate of

endometrial cancer detection by TVS-ET alone,

particularly in relation to factors such as personal

history of cancer or precancerous conditions.

Finally, our findings concerning the acceptable rate

of endometrial cancer detection by TVS-ET reflect

the preferences of women who participated in our

study; they may not be generalisable to populations

with different sociodemographic characteristics or

clinical management pathways.

Conclusions

Clinicians should incorporate patient preferences

concerning the investigation of PMB to enable an

informed choice about invasive testing to exclude

endometrial cancer. Our study population accepted

an endometrial cancer detection rate of 95% by

TVS-ET alone; this rate could be used to guide the

design of future PMB investigation strategies.

Author contributions

Concept or design: LWY Fung, ECW Cheung, ASW Wong, DS Sahota.

Acquisition of data: LWY Fung, ECW Cheung, ASW Wong, DS Sahota.

Analysis or interpretation of data: LWY Fung, DS Sahota.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: LWY Fung, ECW Cheung, ASW Wong, DS Sahota.

Analysis or interpretation of data: LWY Fung, DS Sahota.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the clinical care provided

by gynaecologists and nursing staff at the One-stop

Postmenopausal Bleeding Clinic, Prince of Wales Hospital.

We thank Miss Jennifer SF Tsang for her help with database

management.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained in August 2015 from The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East

Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC Ref

2015.437).

References

1. Astrup K, Olivarius Nde F. Frequency of spontaneously occurring postmenopausal bleeding in the general

population. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand 2004;83:203-7. Crossref

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 426: The role of

transvaginal ultrasonography in the evaluation of

postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:462-4. Crossref

3. Chandavarkar U, Kuperman JM, Muderspach LI, Opper N,

Felix JC, Roman L. Endometrial echo complex thickness

in postmenopausal endometrial cancer. Gynaecol Oncol

2013;131:109-12. Crossref

4. Jacobs I, Gentry-Maharaj A, Burnell M, et al. Sensitivity of

transvaginal ultrasound screening for endometrial cancer

in postmenopausal women: a case-control study within the

UKCTOCS cohort. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:38-48. Crossref

5. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Leading cancer sites in Hong

Kong. Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/.

Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

6. Renaud MC, Le T, SOGC-GOC-SCC Policy and

Practice Guidelines Committee; Special Contributors.

Epidemiology and investigations for suspected endometrial

cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:380-1. Crossref

7. Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal

College of Physicians of Ireland and Directorate of

Clinical Strategy and Programmes, Health Service

Executive. Clinical Practice Guideline. Investigation of

Postmenopausal Bleeding. Guideline No. 26, Version 1.0.

2013. Available from: https://rcpi-live-cdn.s3.amazonaws.

com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/21.-Investigation-of-Postmenopausal-Bleeding.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

8. Ewies AA, Musonda P. Managing postmenopausal

bleeding revisited: what is the best first line investigation

and who should be seen within 2 weeks? A cross-sectional

study of 326 women. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol

2010;153:67-71. Crossref

9. Salman MC, Bozdag G, Dogan S, Yuce K. Role of

postmenopausal bleeding pattern and women’s age in

the prediction of endometrial cancer. Aust N Z J Obstet

Gynaecol 2013;53:484-8. Crossref

10. Tarling R, Gale A, Martin-Hirsch P, Holmes L,

Kanesalingam K, Dey P. Experiences of women referred for

urgent assessment of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB). J

Obstet Gynaecol 2013;33:184-7. Crossref

11. van Hanegem N, Breijer MC, Khan KS, et al. Diagnostic

evaluation of the endometrium in postmenopausal

bleeding: an evidence-based approach. Maturitas

2011;68:155-64. Crossref

12. Dimitraki M, Tsikouras P, Bouchlariotou S, et al. Clinical

evaluation of women with PMB. Is it always necessary

an endometrial biopsy to be performed? A review of the

literature. Arch Gynaecol Obstet 2011;283:261-6. Crossref

13. Clark TJ, Barton PM, Coomarasamy A, Gupta JK, Khan KS.

Investigating postmenopausal bleeding for endometrial

cancer: cost-effectiveness of initial diagnostic strategies.

BJOG 2006;113:502-10. Crossref

14. Karlsson B, Gransberg S, Wikland M, et al. Transvaginal

ultrasonography of the endometrium in women with

postmenopausal bleeding—a Nordic multicenter study.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:1488-94. Crossref

15. Ferrazzi E, Torri V, Trio D, Zannoni E, Filiberto S,

Dordoni D. Sonographic endometrial thickness: a useful

test to predict atrophy in patients with postmenopausal

bleeding. An Italian multicenter study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynaecol 1996;7:315-21. Crossref

16. Smith-Bindman R, Kerlikowske K, Feldstein VA, et al.

Endovaginal ultrasound to exclude endometrial cancer and

other endometrial abnormalities. JAMA 1998;280:1510-7. Crossref

17. Gupta JK, Chien PF, Voit D, Clark TJ, Khan KS.

Ultrasonographic endometrial thickness for diagnosing

endometrial pathology in women with postmenopausal

bleeding: a meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand

2002;81:799-816. Crossref

18. Timmermans A, Opmeer BC, Khan KS, et al. Endometrial

thickness measurement for detecting endometrial cancer

in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynaecol 2010;116:160-7. Crossref

19. Investigation of Post-Menopausal Bleeding. A National

Clinical Guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines

Network; 200

20. Genovese F, D’Urso G, Di Guardo F, et al. Failed diagnostic

hysteroscopy: analysis of 62 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol

Reprod Biol 2020;245:193-7. Crossref

21. Wong AS, Lao TT, Cheung CW, et al. Reappraisal of

endometrial thickness for the detection of endometrial

cancer in postmenopausal bleeding: a retrospective cohort

study. BJOG 2016;123:439-46. Crossref

22. Froberg DG, Kane RL. Methodology for measuring health-state

preferences–II: Scaling methods. J Clin Epidemiol

1989;42:459-71. Crossref

23. Timmermans A, Opmeer BC, Veersema S, Mol BW. Patients’ preferences in the evaluation of postmenopausal

bleeding. BJOG 2007;114:1146-9. Crossref

24. van Osch SM, Stiggelbout AM. The construction of

standard gamble utilities. Health Econ 2008;17:31-40. Crossref

25. Chan YM, Sahota DS, Chan OK, Leung TY, Lau TK.

Miscarriage after invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures:

how much risk our pregnant women are willing to take?

Prenat Diagn 2009;29:870-4. Crossref

26. Chan YM, Sahota DS, Leung TY, Choy KW, Chan OK,

Lau TK. Chinese women’s preferences for prenatal

diagnostic procedure and their willingness to trade

between procedures. Prenat Diagn 2009;29:1270-6. Crossref

27. Chan YM, Leung TY, Chan OK, Cheng YK, Sahota DS.

Patient’s choice between a non-invasive prenatal test and

invasive prenatal diagnosis based on test accuracy. Fetal

Diagn Ther 2014;35:193-8. Crossref

28. Chan YM, Chan OK, Cheng YK, Leung TY, Lao TT,

Sahota DS. Acceptance towards giving birth to a child with

beta-thalassemia major—a prospective study. Taiwan J

Obstet Gynecol 2017;56:618-21. Crossref