Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:24–31 | Number 1, February 2014 | Epub 20 Jun 2013

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133924

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Intensive care unit admission of obstetric

cases: a single centre experience with contemporary update

Vivian KS Ng, MB, ChB, MRCOG1;

TK Lo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; HH

Tsang, MRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; WL Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; WC Leung, MD, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1

1 Department of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Kowloon, Hong Kong

2 Department of Intensive

Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr VKS Ng (vivian_nks@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To review

the characteristics of a series of obstetric patients admitted

to the intensive care unit in a regional hospital in 2006-2010,

to compare them with those of a similar series reported from the

same hospital in 1989-1995 and a series reported from another

regional hospital in 1998-2007.

Design: Retrospective

case series.

Setting: A regional

hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: Obstetric

patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit of Kwong Wah

Hospital from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2010.

Results: From 2006 to

2010, there were 67 such patients admitted to the intensive care

unit (0.23% of total maternities and 2.34% of total intensive

care unit admission), which was a higher incidence than reported

in two other local studies. As in the latter studies, the

majority were admitted postpartum (n=65, 97%), with postpartum

haemorrhage (n=39, 58%) being the commonest cause followed by

pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (n=17, 25%). In the current study,

significantly more patients had had elective caesarean sections

for placenta praevia but fewer had had a hysterectomy. The

duration of intensive care unit stay was shorter (mean, 1.8

days) with fewer invasive procedures performed than in the two

previous studies, but maternal and neonatal mortality was

similar (3% and 6%, respectively).

Conclusion: Postpartum

haemorrhage and pregnancy-induced hypertension were still the

most common reasons for intensive care unit admission. There was

an increasing trend of intensive care unit admissions following

elective caesarean section for placenta praevia and for early

aggressive intervention of pre-eclampsia. Maternal mortality

remained low but had not decreased. The intensive care unit

admission rate by itself might not be a helpful indicator of

obstetric performance.

New knowledge added by this

study

- There was an increasing trend of obstetric intensive care unit (ICU) admissions but with shorter stays.

- Well-planned fertility-sparing treatments for postpartum haemorrhage and placenta praevia may decrease resorting to hysterectomy.

- Other performance indicators in addition to crude ICU admission rates should be established to evaluate obstetric standards.

Introduction

Obstetric admissions to the intensive care

unit (ICU) and maternal mortality continue to have a significant

impact on maternal health care, despite the low rate of such

admissions in developed countries.1

Unlike others, obstetric patients pose a major management

challenge to ICU physicians and obstetricians due to altered

physiology during pregnancy, consideration of fetal wellbeing, and

the unique type of disorders to be dealt with.

Despite ongoing improvements in obstetric

care, more patients were admitted to ICU in the reviewed period

compared with decades earlier.2

Thus, the purpose of this study was to review and compare the

characteristics of obstetric patients admitted to the ICU over the

recent 20 years using historical controls, with respect to their

epidemiology, medical background, antenatal and peripartum risks,

durations of ICU stay, interventions in the ICU, and

predictability of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health

Evaluation (APACHE II) score, as well as maternal and fetal

outcomes.

Methods

This was a retrospective case series of

obstetric patients admitted to the ICU of Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong

Kong, over a 5-year period from 1 January 2006 to 31 December

2010. Our hospital provides joint care with seven other hospitals

in the Kowloon West Cluster to residents of six districts, which

account for about 1.9 million inhabitants. Our obstetric service

is available for 24 hours each day for women in parts of the

Kowloon West and Wong Tai Sin districts. We provide out-patient

and in-patient services, including antenatal check-ups, prenatal

diagnoses, elective and emergency operations and services that are

supported by a blood bank and various laboratory test facilities

available for patients in hospital and in the community. Moreover,

24-hour midwifery, and perinatal and anaesthetic services are

available in our delivery suite. Our team consists of consultants,

associate consultants, as well as senior and junior residents.

Three staff (one specialist, two residents) are always available

on site for emergency admissions. Annually, we manage 5000 to 6000

deliveries, which is one of the highest delivery rates for a Hong

Kong hospital. Our ICU was established in 1968, currently has 14

beds, and admits 500 to 600 patients every year. The ICU team

consists of a critical care physician, a resident anaesthetist,

medical and surgical residents, and a nursing team with critical

care–registered nurse specialists.

This study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority. No

patient consent was required as the study only involved review of

medical records.

Obstetric patients from 24 weeks of

gestation onwards to 6 weeks postpartum admitted to the ICU were

reviewed. They were identified via the computerised database

system adopted by the ICU. All corresponding medical records were

reviewed in detail. Supplementary information was retrieved from

the Clinical Management System, Electronic Patient Record, and

Obstetrics Clinical Information System.

Data retrieved for analysis included

patient demographics (age, ethnicity, smoking and drinking status,

parity, order of pregnancy, and body mass index [BMI] at booking

visit), antenatal booking status, number of antenatal visits,

medical history, perinatal risks, gestation at and mode of

delivery, indications for caesarean section, interventions

involved at and after delivery, indications and admission status

to the ICU, and maternal and fetal outcomes. Patient mortality was

predicted by recourse to the APACHE II score.

Indications for ICU admission were divided

into obstetric and non-obstetric causes. Obstetric causes were

those unique to pregnancy or liable to occur within 6 weeks of

delivery. Non-obstetric causes were those not specifically related

in pregnancy.

Interventions provided by ICU physicians

were classified into non-invasive and invasive. Those deemed

non-invasive included insertion of arterial or central lines,

blood product transfusion, use of continuous positive airway

pressure (CPAP) ventilation, and use of inotropes. Invasive

procedures included invasive mechanical ventilation,

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation, and

haemodialysis.

Immediate and long-term complications of

the mothers and neonates were assessed up to 6 to 8 weeks

post-delivery. Maternal and perinatal mortalities were also

calculated.

Data were entered manually into Excel and

analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(SPSS version 17, Chicago [IL], US). The data were compared with

those from the results of a historical review in the same hospital

(1989-1995, by Tang et al2)

and a review in another regional hospital (1998-2007, by Leung et

al3). Chi squared or

Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare proportions and

Student’s t test to compare continuous variables.

Results

In all, 67 relevant patients were admitted

to the ICU and reviewed during the period of 1 January 2006 to 31

December 2010, which amounted to 0.23% of the total hospital

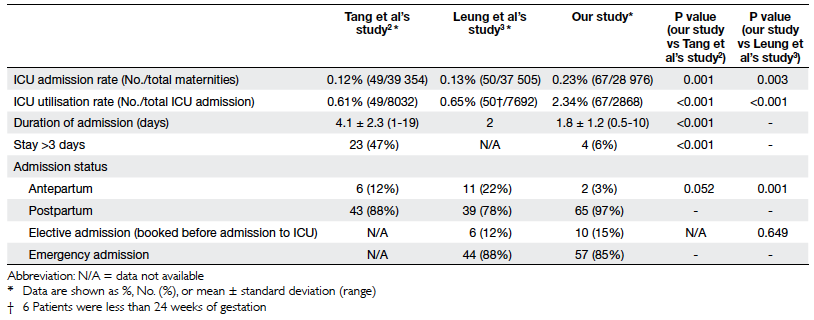

maternities and 2.34% of all ICU admissions (Table 1).

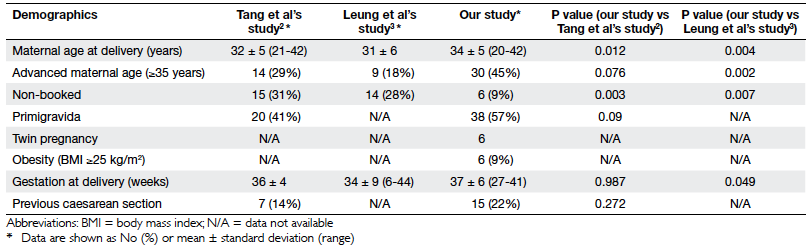

Their demographic features are shown in Table 2. The mean age of women at delivery

was 34 (standard deviation [SD], 5; range, 20-42) years. Thirty

(45%) of the patients were of advanced maternal age (ie age at

confinement of ≥35 years). The majority of them were Chinese

(n=65, 97%), one was Filipino and one an Indonesian. Nine (13%)

patients were visitors from mainland China. Seven (10%) were

smokers, two (3%) drank alcohol regularly and two (3%) had a

history of substance abuse. In all, 38 (57%) were nulliparous and

six (9%) carried twin pregnancies. Most of the patients (n=61,

91%) were booked in our unit; 19 (28%) had three antenatal

check-ups or less.

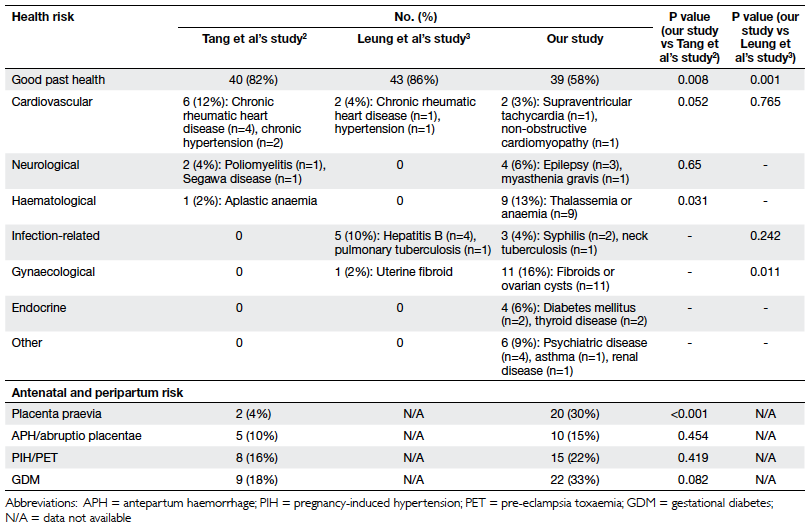

Among these 67 patients, 39 (58%) enjoyed

good past health, and six (9%) had a BMI of more than 25 kg/m2 at

their booking visit. The most common co-existing diseases were

gynaecological (n=11, 16%) and haematological (n=9, 13%). Their

antenatal and peripartum risks are summarised in Table 3.

The mean gestational age at delivery was 37

(SD, 6; range, 27-41) weeks. Most of them were delivered by

emergency caesarean section (n=34, 51%), including one transferred

to us after delivery in the private sector. One patient remained

undelivered and died antenatally. Placenta praevia and

pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders were the main indications

for elective and emergency caesarean sections, respectively. Other

indications are listed in Table 4.

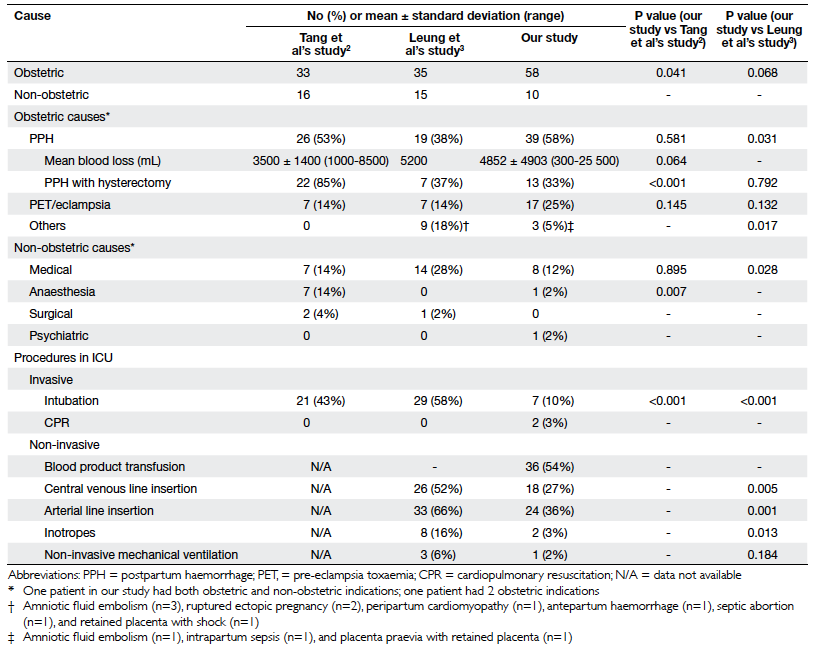

The reasons for ICU admission and

procedures undertaken therein are listed in Table 5.

Most were admitted to the ICU postpartum (n=65, 97%) and for

obstetric problems (n=58, 87%), of which postpartum haemorrhage

(PPH) was the leading cause (n=39, 58%) followed by pre-eclamptic

toxaemia (PET) or eclampsia (n=17, 25%). The mean duration of ICU

stay was 1.8 (SD, 1.2; range, 0.5-10) days; four (6%) of the

patients stayed for more than 3 days.

In all, 39 patients were admitted to the

ICU due to a PPH, the mean estimated blood loss was 4852 mL. Major

causes of PPH were related to placenta praevia (n=16), uterine

atony (n=12), and perineal trauma (n=5). Blood products given

included packed cells (mean, 12 units), platelet concentrate

(mean, 5 units), fresh frozen plasma (mean, 7 units), and

cryoprecipitate (mean, 1 unit). Three patients received

recombinant factor VIIa (NovoSeven; Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd,

Denmark). Procedures to control PPH included compression sutures

(n=10), uterine artery embolisation (n=9), insertion of a

Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (n=6), and uterine artery ligation

(n=2). There were 13 patients who underwent hysterectomy despite

multiple other interventions and use of multiple uterotonics, and

eight patients with PPH were complicated with disseminated

intravascular coagulation, one had a ventricular tachycardia, and

one had a urinary tract injury. One of the patients with a PPH and

anaphylactic shock suffered a cavernous sinus thrombosis and a

cranial nerve VI palsy, for which she received therapeutic doses

of low-molecular-weight heparin. Another patient was admitted 2

weeks after delivery due to delirium secondary to sepsis.

There were 17 patients admitted to the ICU

for PET or eclampsia (9 of whom had eclampsia) and were all

stabilised in the ICU. Two patients had HELLP (haemolysis,

elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) syndrome and two had

hypertensive encephalopathy diagnosed on the basis of computed

tomography. Other complications included acute pulmonary oedema

(n=1), deranged renal function (n=3), deranged liver function

(n=1), and aspiration pneumonitis (n=1). Another eight had

persistent hypertension 6 weeks postpartum and were referred to

physicians.

Regarding the 10 patients (15% of the

cohort) admitted to the ICU for non-obstetric reasons, two had an

epileptic seizure, three had cardiovascular problems

(cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and pulmonary hypertension), and

one each had renal disease, ethanol toxicity, acute pulmonary

oedema, myasthenia gravis, and anaphylactic shock.

Invasive procedures performed in the ICU

were CPR (n=2, 3%) and mechanical ventilation (n=7, 10%).

Non-invasive procedures were blood product transfusions (n=36,

54%), central line insertion (n=18, 27%), arterial line insertion

(n=24, 36%), use of inotropes (n=2, 3%), and CPAP ventilation

(n=1, 2%).

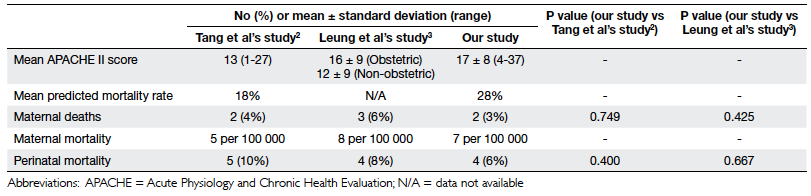

The mean APACHE II score was 17 (range,

4-37) and the mean predicted mortality rate was 28% (range,

4-85%). The actual mortality rate in this series was 3% (Table 6).

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR; actual/predicted mortality) was

0.11.

In our study period, there were two

maternal deaths in the 28 976 maternities or 7 per 100 000 births,

both in ICU patients. One was a patient who enjoyed good health

but suspected to have pulmonary hypertension at 27 weeks of

gestation, who rapidly deteriorated and died 1 day after

admission. Her diagnosis was confirmed at postmortem examination.

The other maternal death ensued in the postpartum period due to

multi-organ failure and brain death, secondary to eclampsia and

intraventricular haemorrhage.

Regarding these ICU admissions, three (5%)

of the fetuses endured intrauterine death (IUD) and one (2%) whose

neonate died (due to necrotising enterocolitis). The IUDs were

associated with abruptio placentae, pulmonary hypertension, and

severe pre-eclampsia with early intrauterine growth restriction.

Discussion

The health care system of Hong Kong aims to

protect/ improve maternal and child health, by means of antenatal,

intrapartum, and postnatal services that are readily available at

very low costs. Whilst the MMR fluctuated between 1.0 and 11.2 per

100 000 live births over the past 31 years,4 5 the

above-mentioned services have contributed to the decreasing and

now very low maternal mortality rates.

Despite advances in obstetric care, the

admission rate to the ICU had doubled compared with a decade ago

(from 0.12% to 0.23%).2

Whereas such ICU utilisation rates for obstetric cases were also

higher compared with Tang et al’s data2

(2.34% vs 0.61%), nevertheless they were low compared to reports

from overseas.6 7 The rates were also higher than those reported

by Leung et al (admission, 0.13%; utilisation, 0.65%).3 One of the reasons for the rise in ICU

admission rates was changes in patient allocation in our hospital,

and over the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The number

of beds in our ICU was reduced from 18 to 14 after the severe

acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in 2003. The number of

surgical admissions was also much lower than a decade earlier.

Moreover, the number of trauma cases dropped significantly, since

two other nearby tertiary hospitals became trauma centres.

Changing attitudes of obstetricians and anaesthetists also

contributed to the increase in ICU admission rate. Given the fact

that our patients were most commonly delivered by elective

caesarean section for placenta praevia, a proper preoperative

management plan with a multidisciplinary approach involving

anaesthetist, intensive care physician, and obstetricians should

have been available before the operation, which included booking

of the ICU bed. With the increasing trend of placenta praevia, it

was expected that more and more patients would be admitted to the

ICU electively for monitoring rather than any future active

intervention. The shorter duration of ICU stays, compared with

those detailed earlier by Tang et al,2

is probably consistent with this trend towards elective

admissions.

The mean age of our patients at delivery

was higher than that in the patient series described by Tang et

al2 and Leung et al.3

Indeed, patients of advanced maternal age were more likely to be

admitted to the ICU when compared with our background population,

though this was not shown for such ICU admissions reported by

Selo-Ojeme et al.8

Increasing maternal age implies that our patients were more likely

to have co-existing diseases complicating pregnancy, as reflected

by our data, even though the medical problems in question were

generally mild and stable.

According to Tang et al’s2 and Leung et al’s3

reports about non-booked cases (NBCs), patients from mainland

China used to be admitted via the emergency department very late

when they went into advanced labour. As a result, potential or

present obstetric complications were known to us only when they

were admitted. With the commencement of the policy to allow these

mothers to register and deliver in Hong Kong (since 2007), the

number of NBCs decreased significantly, as did their number of ICU

admissions.

In the literature there are conflicting

data when parity is considered one of the risk factors for ICU

admission. In our study, nulliparity was not related to ICU

admission, which was also what Pollock et al noted.6

During our data analysis, twin pregnancy

was more likely in our ICU patients compared with the background

population. However, such data cannot be retrieved from Tang et

al’s or Leung et al’s reports.2

3 Twin pregnancy is known

to confer a higher risk of gestational diabetes, hypertension,

premature delivery, operative deliveries, and postpartum

complications (including PPH).9

10 Our findings also

supported the need of a specialised twin pregnancy clinic to look

after this high-risk group.

Placenta praevia was the most frequent risk

factor identified in our patient series, being much more common

than in Tang et al’s study.2

Increasing popularity of evaluation by ultrasound has raised the

detection rate of placenta praevia early in the antenatal period.

All our patients with placenta praevia were delivered electively

with proper preoperative arrangements. These entailed booking of

ICU facilities, standby uterine artery embolisation, preparation

of recombinant factor VIIa and Sengstaken-Blakemore tubes, and

involvement of obstetric consultants to make decisions. One

consequence was a significantly higher number of elective

caesarean sections for placenta praevia compared with decades ago,

though the overall section rate remained relatively stable.11 This also correlated with placenta praevia

being the commonest causes of PPH in our ICU patients.

As in Tang et al’s2

and Leung and et al’s3

studies, in our series admissions due to obstetric problems

remained the main cause of obstetric ICU admissions. Postpartum

haemorrhage was consistently the most common indication for ICU

admission, which was also noted in Tang et al’s series.2 Although the mean estimated blood loss of our

patients was apparently higher than that reported by Tang et al,2 and abdominal delivery is

known to increase the risk of hysterectomy following PPH,12 the number of hysterectomies performed was

significantly lower than before. The increasing use of compression

sutures and uterine artery embolisation together with strategies

to retain the placenta in cases of placenta accreta might account

for the decreasing recourse to hysterectomy compared with 20 years

ago.

The current series had more patients with

pre-eclampsia or eclampsia admitted to the ICU than those reported

by Tang et al,2 although

the difference was not statistically significant. As suggested by

the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

guideline,12 our management

protocol was updated to incorporate the more liberal use of

antihypertensives and magnesium sulphate. Our use of the modified

early obstetric warning scoring system allowed early detection of

potential complications to prevent poor obstetric outcomes.

Intensive care is indicated in patients with severe hypertension,

or moderate hypertension with symptoms of impending eclampsia or

any suggestion of organ dysfunction. These innovations lead to the

rising trend of ICU admissions to monitor for pre-eclampsia.

Active involvement of anaesthetists plays a

role in the changing pattern of obstetric ICU admissions. There

was a drastic reduction of admissions for anaesthesia-related

causes compared with those reported by Tang et al.2 Only one of our patients was admitted due to

anaphylactic shock, which can be explained by the significant

improvements in anaesthetic care and mechanical ventilation in our

hospital. Invasive and non-invasive procedures (eg intubation and

insertion of arterial and central venous lines) undertaken in the

ICU were significantly fewer than decades ago, as most of them had

been performed before admission to ICU by anaesthetists.

In our series, the mean duration of ICU

stay was 1.8 days, which was shorter than 4.1 days reported in

Tang et al’s study.2 The

change in attitude and approach to management of both

obstetricians and anaesthetists made ICU admission a more elective

occurrence than before. As a result, patients admitted to the ICU

tended to be more stable and fewer invasive interventions were

warranted. These observations highlight the need for obstetric

high-dependency units to cater for patients requiring more

intensive care, but not to the extent of ICU support.13

When compared with the findings reported by

Leung et al,3 over the

decades there was no significant increase in perinatal mortality,

nor was there an increased rate of fetal loss when compared with

our background population. Nevertheless, maternal mortality had

not decreased. In our series, there were two maternal deaths that

amounted to a mortality rate of 7 per 100 000 maternities. In Tang

et al’s series2 the

maternal mortality was 5 per 100 000, and in the UK it was

reported to be 14 and 11 per 100 000 in 2003-2005 and 2006-2008,

respectively.14 However,

these differences between series were not statistically

significant.

One limitation of our study was that data

collection from the computerised system might have omitted

pregnant women admitted to the ICU from other specialties with

diagnoses that were not obstetrically related. A second limitation

was that the causes of maternal ICU admission may not relate

directly to the causes of maternal mortality. For example,

thromboembolism, one of the leading causes of maternal death in

the UK, was not a major cause of ICU admission. In the UK, only

30% of such maternal deaths were in patients admitted to the ICU,15 and on this issue there

is no global consensus on the optimal indications for ICU

admission. A third limitation was that the frequency of obstetric

ICU admissions is also affected by the standard of obstetric care

and the threshold admission criteria determined by obstetricians,

anaesthetists, and intensive care physicians. As a result, ICU

admissions may not truly reflect the standard of obstetric care.16 A composite performance

indicator of obstetric care by combining the frequency of ICU

admission, numbers of emergency admissions and/or proportions of

emergency/elective admissions, and proportions having prolonged

stays (eg >3 days) could be a more useful measure of the

standard of obstetric practice in the future.

The APACHE II scoring system has been used

as a quantitative predictor of mortality, mainly in medical and

surgical patients admitted to the ICU using several physiological

measures. Its potential has also been evaluated when applied to

obstetric patients. According to different overseas reviews, it

may overestimate risks in pregnant patients, as in them normal

physiology can differ, often in subtle ways, and can undergo

abrupt changes in various emergency conditions.17 18

Thus, to date, there is still no proper screening system for

obstetric emergencies. A specific scoring system for obstetric

patients should be developed and warrants a large-scale

international prospective study for this purpose.

The majority of patients discharged from

our ICU enjoyed satisfactory recoveries in the puerperal period.

In all, eight patients with hypertensive disorder in pregnancy had

persistent hypertension for which they were referred for medical

assessment. In our series, long-term outcome was not determined.

Leung et al3 found that

women admitted to the ICU had lower mean scores for quality of

life than normal Hong Kong females of similar age, but these

authors commented that the relationship of low scores to the

obstetric illnesses was unclear and might be resolved by long-term

patient follow-up.

In some respects, Leung et al’s study3 also provided us with geographical controls.

However, they included patients with gestational ages of <24

weeks, which complicated any comparison of risk factors. Moreover,

being intensive care physicians they emphasised quality of life

after discharge from the ICU. In contrast, we obstetricians looked

for indicators to prevent/reduce maternal ICU admissions, as

advocated in modern obstetrical care guidelines.

Conclusion

Our findings illustrate the various

changes in ICU admission practice of obstetric cases in the last

20 years, and are comparable to those in other developed

countries. Elective caesarean section for placenta praevia and PPH

were the major reasons for ICU admission. More conservative

management of placenta praevia and PPH appeared to reduce

resorting to hysterectomy. These ongoing changes in practice may

make emergency obstetric admissions to the ICU less likely in the

future. Maternal mortality in our unit has remained low over the

years, and can hardly be reduced any further. It is therefore more

important to refine and improve obstetric practice to reduce

maternal morbidity. The ‘near-miss’ in terms of obstetric ICU

admission rates, together with measures targeting the duration of

ICU stay, and a potential obstetric morbidity scoring system will

no doubt better reflect our clinical performance standards in the

future.

References

1. Public Health Agency of Canada.

Make every mother and child count: report on maternal and child

health in Canada. 2005. Available from:

http://publications.gc.ca/collections/

Collection/H124-13-2005E.pdf. Accessed Jun 2010.

2. Tang LC, Kwok AC, Wong AY, Lee

YY, Sun KO, So AP. Critical care in obstetrical patients: an

eight-year review. Chin Med J (Engl) 1997;110:936-41.

3. Leung NY, Lau AC, Chan KK, Yan

WW. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of obstetric patients

admitted to the intensive care unit: a 10-year retrospective

review. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:18-25.

4. Department of Health, Hong Kong.

Chapter 1: Health of community. Annual Report 2009/2010.

5. Department of Health, Hong Kong.

Number of maternal deaths by major disease group, 2001-2009.

Available from: www.healthyhk.gov.hk/phisweb/reports/2009_01_01_

MOT00101.xls. Accessed Aug 2010.

6. Pollock W, Rose L, Dennis CL.

Pregnant and postpartum admissions to the intensive care unit: a

systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:1465-74. Crossref

7. Togal T, Yucel N, Gedik E,

Gulhas N, Toprak HI, Ersoy MO. Obstetric admissions to the

intensive care unit in a tertiary referral hospital. J Crit Care

2010;25:628-33. Crossref

8. Selo-Ojeme DO, Omosaiye M,

Parijat Battacharjee P, Kadir RA. Risk factors for obstetric

admissions to the intensive care unit in a tertiary hospital: a

case-control study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2005;272:207-10. Crossref

9. Liu AL, Yung WK, Yeung HN, et

al. Factors influencing the mode of delivery and associated

pregnancy outcomes for twins: a retrospective cohort study in a

public hospital. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:99-107.

10. Yung WK, Liu AL, Lai SF, et

al. A specialised twin pregnancy clinic in a public hospital. Hong

Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2012;12:21-32.

11. Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital. Annual Report 2006-2010.

12. National Institute for Health

and Clinical Excellence. Caesarean section. NICE Clinical

Guidelines, No 132. 2010.

13. Mirghani HM, Hamed M,

Ezimokhai M, Weerasinghe DS. Pregnancy-related admissions to the

intensive care unit. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004;13:82-5. Crossref

14. Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T,

Cooper G, et al. Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths

to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The eighth report on

confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom.

BJOG 2011;118(Suppl 1):1S-203S. Crossref

15. Lewis G, Clutton-Brock T,

Cooper G, et al. Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths

to make motherhood safer–2003-2005. The seventh report on

confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom.

London: CEMACH; 2007.

16. Baskett T, Sternadel J.

Maternal intensive care and near-miss mortality in obstetrics. Br

J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:981-4. Crossref

17. Vasquez DN, Estenssoro E,

Canales HS, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of

obstetric patients requiring ICU admission. CHEST 2007;131:718-24.

Crossref

18. Gilbert TT, Smulian JC, Martin

AA, et al. Obstetric admissions to the intensive care unit:

outcomes and severity of illness. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:897-903.

Crossref